Jean-Baptiste Greuze stands as a fascinating and somewhat paradoxical figure in the rich tapestry of 18th-century French art. Flourishing during a period of significant cultural and stylistic transition, Greuze carved a unique niche for himself, moving away from the frothy elegance of the high Rococo towards a more emotionally charged and morally didactic form of genre painting. His works resonated deeply with the sensibilities of the Enlightenment era, capturing the burgeoning interest in domestic virtue, natural feeling, and the lives of the ordinary bourgeoisie. Praised by influential critics like Denis Diderot yet simultaneously embroiled in conflict with the powerful Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, Greuze's career trajectory mirrored the complex currents of his time. He achieved immense popularity, only to see his style fall out of favour with the rise of Neoclassicism, ultimately dying in relative obscurity. Yet, his legacy endures through his powerful depictions of family life, his sensitive portraiture, and his pioneering role in infusing genre painting with dramatic intensity and psychological depth, setting him apart from contemporaries like François Boucher or Jean-Honoré Fragonard and prefiguring aspects of later artistic movements.

Humble Beginnings and Artistic Formation

Jean-Baptiste Greuze was born on August 21, 1725, in Tournus, a town in the Burgundy region of France. His origins were modest; his father worked as a tiler or master mason, and his mother was reportedly a baker. This background placed him outside the established circles from which many artists of the era emerged. Despite this, young Greuze displayed an early aptitude and passion for drawing, eventually overcoming initial paternal resistance to his chosen path. His family, recognizing his talent, permitted him to pursue artistic training.

His formal artistic education began not in the bustling capital, but in Lyon, a significant provincial center. There, he entered the studio of Charles Grandon, a local portraitist. While details of this apprenticeship are somewhat scarce, it likely provided Greuze with foundational skills in drawing and painting, particularly in capturing likenesses, a skill that would serve him well throughout his career. Lyon's artistic scene, though less prominent than Paris's, offered opportunities for a budding artist to hone his craft away from the intense competition of the capital.

Around 1750, seeking greater opportunities and exposure, Greuze made the pivotal move to Paris. The city was the undisputed heart of the French art world, dominated by the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and the influential Salons, the official art exhibitions. Greuze is believed to have briefly studied at the Academy school, possibly encountering figures like Charles-Joseph Natoire, although Natoire's primary influence might have been earlier or indirect. The dominant style was Rococo, championed by artists like François Boucher and Carle Van Loo (who later became director of the Academy school), characterized by its lightness, elegance, and often mythological or aristocratic themes. Greuze, however, seemed destined to follow a different path.

The Salon Debut and Rise to Prominence

The year 1755 marked a turning point in Greuze's career. He made his debut at the prestigious Paris Salon, the official exhibition that could make or break an artist's reputation. Greuze submitted several works, but one, in particular, caused a sensation: Father Reading the Bible to His Children (also known as Father Explaining the Bible to His Family). This painting depicted a humble, multi-generational family gathered attentively as the patriarch reads from the scriptures. Its sober realism, heartfelt emotion, and clear moral message struck a chord with the public and critics alike.

The work stood in stark contrast to the prevailing Rococo taste. Instead of playful gods or aristocratic dalliances, Greuze presented a scene of bourgeois piety and domestic harmony. Its detailed execution recalled the Dutch Golden Age masters like Rembrandt or Gerard Dou, while its emotional weight aligned perfectly with the growing "cult of sensibility" fostered by Enlightenment thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who emphasized natural virtue and feeling.

The influential philosopher and art critic Denis Diderot became one of Greuze's most ardent champions. Reviewing the 1755 Salon, Diderot lavished praise on Father Reading the Bible, declaring, "This is moral painting!" He admired its truthfulness, its emotional impact, and its departure from frivolous subjects. Diderot saw Greuze as an artist who could instruct and improve the viewer, aligning art with the Enlightenment project of promoting virtue and reason. This critical endorsement significantly boosted Greuze's standing. On the strength of this debut, Greuze was quickly agréé by the Academy – accepted as an approved candidate for full membership.

Shortly after this triumph, Greuze embarked on a trip to Italy (1755-1757), accompanied by the Abbé Louis Gougenot, an art enthusiast and collector. Italy was considered an essential destination for any ambitious artist, a place to study classical antiquity and the Renaissance masters. Curiously, however, the experience seems to have had less impact on Greuze's style than might be expected. He showed little interest in history painting or classical sculpture, focusing instead on contemporary Italian life and perhaps the genre scenes of artists like Pietro Longhi. He returned to Paris not as a convert to the Grand Manner, but seemingly more confirmed in his dedication to depicting contemporary life and emotion.

Defining a Style: Moral Genre Painting and Sensibility

Upon his return from Italy, Greuze solidified his reputation as the leading exponent of a new type of genre painting – one imbued with moral purpose and heightened emotionalism. He became the master of what Diderot termed peinture morale (moral painting). This wasn't simply about depicting everyday life, as Jean Siméon Chardin did with quiet dignity; Greuze aimed to tell stories, often with clear lessons about virtue, duty, and the consequences of vice.

His subjects were typically drawn from the lives of the bourgeoisie or prosperous peasantry. He depicted scenes of family harmony, parental authority, education, charity, and the dramas of courtship and marriage. These themes resonated deeply with an audience increasingly interested in the values of the family unit and the perceived honesty of middle-class life, often contrasted implicitly with the perceived decadence of the aristocracy. The philosophical underpinnings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, emphasizing innate human goodness and the importance of sentiment, provided fertile ground for Greuze's art.

Technically, Greuze developed a distinctive style. He combined meticulous, almost Dutch-inspired realism in rendering textures and details with a highly theatrical sense of composition and expression. His figures often adopt dramatic poses and display exaggerated facial expressions – tears, frowns, clasped hands – designed to convey specific emotions and drive home the narrative's message. This theatricality, while effective in engaging the viewer's emotions, would later draw criticism for bordering on melodrama or sentimentality. His brushwork was generally smooth and polished, allowing for fine detail, and his use of light and shadow often served to heighten the dramatic focus. He differed significantly from Chardin's quieter, more contemplative approach, opting instead for narrative clarity and emotional impact.

Masterpieces of Sentiment and Drama

The years following his return from Italy saw Greuze produce some of his most celebrated and characteristic works, cementing his fame and popularity.

The Village Bride (L'Accordée de Village), exhibited at the 1761 Salon, was an overwhelming success, perhaps his most famous work during his lifetime. It depicts the moment a marriage contract is formalized in a rustic setting. The notary sits at a table while the father hands over the dowry to the groom, who tenderly holds his bride's arm. The bride appears modest and slightly melancholic, while her mother and younger sister weep openly. The scene is a complex tableau of familial emotions – paternal authority, marital agreement, sisterly affection, and the bittersweetness of departure. Diderot hailed it as Greuze's masterpiece, praising its composition, expression, and moral tone. The painting's popularity was immense, widely reproduced in engravings, making Greuze a household name.

Greuze also explored the darker side of family life in pendants like The Father's Curse: The Ungrateful Son (c. 1777) and The Father's Curse: The Punished Son (c. 1778). These works form a dramatic narrative sequence. In the first, an angry father curses his son who is leaving home against his wishes, possibly to join the army, while the family tries to intervene. The second painting shows the tragic aftermath: the son has returned, wounded and repentant, only to find his father dead or dying, surrounded by his grieving family. These works are highly theatrical, employing dramatic gestures and intense expressions to convey the themes of filial disobedience, paternal authority, and the devastating consequences of family conflict. They represent Greuze at his most overtly moralizing and melodramatic.

A different kind of sentiment is explored in The Broken Pitcher (La Cruche Cassée), painted around 1771. This iconic image shows a young girl, clad in simple white dress with a pink ribbon, holding a cracked water pitcher, flowers spilling from her apron. Her expression is one of subtle distress and perhaps shame. The painting became immensely popular, interpreted widely as an allegory for the loss of virginity or innocence. Its delicate sensuality, combined with the girl's apparent vulnerability, proved captivating. It showcased Greuze's ability to convey complex emotions through subtle means, contrasting with the more overt drama of the Father's Curse series.

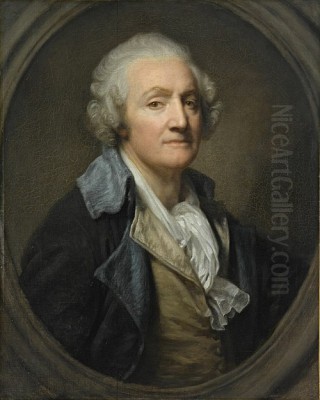

Other significant works include The Charitable Lady (La Dame de Charité, possibly later 1770s), depicting a wealthy woman visiting a poor family, embodying the virtue of bourgeois benevolence, and numerous sensitive portraits. Greuze was a skilled portraitist, capturing the psychological presence of his sitters, whether famous actresses like Sophie Arnould or members of his own family. His portraits often share the emotional directness of his genre scenes, comparing interestingly with the more formal or idealized portraits by contemporaries like Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun or Adélaïde Labille-Guiard.

The Contentious Relationship with the Academy

Despite his immense public popularity and the support of critics like Diderot, Greuze's relationship with the powerful Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture was fraught with tension. The core of the conflict lay in the Academy's strict hierarchy of genres. History painting – depicting classical, mythological, or biblical scenes with noble themes and complex multi-figure compositions – occupied the highest rank. Portraiture, genre painting, landscape, and still life were considered lower categories.

Greuze, ambitious and perhaps proud, aspired to be recognized as a history painter, the most prestigious title. In 1769, he submitted his reception piece for full membership: Septimius Severus Reproaching Caracalla. This painting depicted a scene from Roman history, a clear attempt to meet the criteria for history painting. However, the Academy, perhaps wary of Greuze's independent streak or genuinely unconvinced by his handling of the historical subject compared to his genre scenes, delivered a stinging verdict. They accepted him as a full member, but explicitly classified him as a genre painter, based on the strength of his previous work, effectively dismissing his historical ambitions.

This decision, perceived by Greuze as a public humiliation, became known as the "Greuze Affair." Deeply offended, Greuze essentially broke ties with the Academy. He refused to exhibit at the official Salon for many years, choosing instead to display his works privately in his studio. This move, while asserting his independence, potentially limited his access to major commissions and official patronage. He relied increasingly on private collectors and the lucrative market for engravings after his paintings, which disseminated his images widely across Europe. The conflict highlighted the rigid structures of the art establishment and Greuze's own complex personality, a mix of ambition, sensitivity, and perhaps stubbornness. Figures within the Academy, like the sculptor Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, represented the established order with which Greuze clashed.

Personal Life and Its Shadows

Greuze's personal life was also marked by turmoil, particularly his marriage to Anne-Gabrielle Babuty, the daughter of a Parisian bookseller, whom he married in 1759. Initially, Anne-Gabrielle seems to have played an active role in managing his studio and the profitable business of print reproductions. However, the marriage deteriorated significantly over time. Contemporary accounts and later biographies paint a picture of Anne-Gabrielle as extravagant, flirtatious, and neglectful of her domestic duties.

Greuze himself, in letters and recorded conversations, expressed deep bitterness about his wife's conduct. Her alleged infidelities and financial mismanagement were sources of constant conflict and distress. It's reported that her behaviour alienated some of Greuze's patrons and even students; one anecdote suggests that Jean-Jacques Rousseau ceased visiting Greuze due to Anne-Gabrielle's perceived impropriety. The emotional strain of this relationship may well have influenced the themes of domestic discord and betrayal that appear in some of his later works.

The couple eventually separated, and a messy divorce was finalized in 1793, during the upheaval of the French Revolution. Greuze had several students, including talented women artists like Constance Mayer (who later formed a close professional and personal relationship with Pierre-Paul Prud'hon). However, the instability of his domestic life likely cast a shadow over these professional relationships as well. The contrast between the idealized domestic virtue often depicted in his paintings and the apparent chaos of his own household is a poignant irony of Greuze's life.

Changing Tastes and Later Decline

While Greuze dominated the sentimental genre scene in the 1760s and 1770s, the artistic landscape of France began to shift dramatically in the 1780s. The Rococo's lightness and Greuze's brand of emotionalism started to give way to the more austere, rational, and morally serious style of Neoclassicism. Championed by Jacques-Louis David, whose Oath of the Horatii (1784) became a manifesto for the new style, Neoclassicism emphasized clear lines, sober colours, classical themes, and civic virtue.

In this new climate, Greuze's work began to seem old-fashioned, even excessively sentimental or theatrical. The very qualities that Diderot had praised – the overt display of emotion, the focus on domestic drama – were now seen by some critics as lacking in gravitas and intellectual rigor compared to the heroic stoicism promoted by David and his followers, like Jean-Germain Drouais. The French Revolution further accelerated this shift; the intense emotionalism of Greuze's paintings seemed out of step with the Revolution's emphasis on reason and republican ideals, though some revolutionary figures initially saw value in his depictions of common life.

Greuze attempted to adapt, occasionally tackling historical or allegorical subjects, but he never truly embraced the Neoclassical aesthetic, nor did these works achieve the success of his earlier genre paintings. Commissions dwindled, and the market for his specific style softened. Compounded by financial mismanagement (perhaps exacerbated by his wife's alleged extravagance and the costs of their separation and divorce), Greuze found himself in increasingly difficult circumstances.

Final Years, Death, and Legacy

The final decade of Greuze's life was marked by declining fame and financial hardship. He continued to paint, particularly portraits, but he struggled to regain the prominence he had once enjoyed. The Revolution had disrupted old patterns of patronage, and the Napoleonic era favoured the grand Neoclassical style of David and his school. Greuze lived long enough to see his own approach become marginalized.

He died in Paris on March 21, 1805, in relative poverty and obscurity. His passing garnered little attention compared to the sensation his early works had caused half a century earlier. At the time of his death, his reputation was at a low ebb, overshadowed by the towering figure of David and the triumph of Neoclassicism.

However, Greuze's legacy proved more resilient than his late career might suggest. Engravings after his works remained popular, ensuring his images continued to circulate. While the 19th century largely dismissed him as overly sentimental, a critical re-evaluation began towards the end of the century. Writers like the Goncourt brothers (Edmond and Jules de Goncourt) and Théophile Gautier rediscovered his work, praising his technical skill, his psychological acuity, and the genuine feeling underlying the sometimes theatrical presentation. They saw beyond the moralizing to appreciate his sensitive portrayal of childhood, adolescence, and complex family dynamics.

Today, Jean-Baptiste Greuze is recognized as a major figure in 18th-century French art. He occupies a crucial position between the Rococo and Neoclassicism, reflecting the Enlightenment's complex "age of sensibility." His dedication to moral genre painting elevated the status of depicting everyday life, infusing it with unprecedented emotional weight and narrative drama. While his overt sentimentality can sometimes feel alien to modern tastes, his best works – like The Village Bride or The Broken Pitcher – retain their power to engage and move the viewer. His influence can be traced in later artists interested in emotional expression and narrative painting, perhaps even touching aspects of Romanticism seen in the expressive studies of Théodore Géricault or the narrative focus of Victorian painters.

Conclusion: An Artist of His Time

Jean-Baptiste Greuze remains a compelling figure, an artist whose work perfectly encapsulated the complex blend of reason and sentiment that characterized the French Enlightenment. From humble beginnings, he rose to extraordinary fame through his innovative and emotionally charged depictions of bourgeois life. His "moral paintings" resonated with a public eager for art that reflected their values and stirred their feelings. His clashes with the Academy reveal both his own ambition and the rigid hierarchies of the established art world. Though his star faded with the rise of Neoclassicism and he faced personal and financial difficulties, his contribution to art history is undeniable. He broadened the scope of genre painting, explored human psychology with sensitivity, and left behind a body of work that continues to offer insight into the social and emotional landscape of 18th-century France. Greuze was, in essence, a painter who dared to make everyday emotions the stuff of high art.