Hugues Merle stands as a significant figure in French painting during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Born in 1823 and passing away in 1881, his career unfolded during a dynamic period of artistic change in France, bridging the established traditions of Academic art with emerging currents of Realism and Naturalism. While perhaps less universally recognized today than some of his contemporaries, Merle enjoyed considerable success during his lifetime, celebrated for his technical skill and his poignant explorations of sentimental, moral, and religious themes. His work, often characterized by its delicate execution and emotional depth, found favour with critics, collectors, and the juries of the influential Paris Salon.

Merle's artistic journey provides a fascinating window into the tastes and values of his era. He navigated the competitive Parisian art world, establishing a distinct niche for himself, particularly through his sensitive portrayals of maternal affection and childhood innocence. Often compared to his highly successful contemporary, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Merle carved out his own path, earning accolades and securing patronage both in France and, notably, in the United States. Understanding Hugues Merle requires appreciating the context of Academic training, the power of the Salon system, and the public appetite for art that resonated with familiar human emotions and moral narratives.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Hugues Merle was born on April 28, 1823, in the village of Saint-Marcellin, located in the Isère department of southeastern France. This area, near the Isère River valley, possessed a rich history, providing a perhaps unassuming, yet traditional, backdrop for the future artist's formative years. Like many aspiring artists of his generation seeking formal training and career opportunities, Merle eventually made his way to the epicentre of the French art world: Paris.

In 1843, Merle enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the leading institution for artistic education in France. There, he became a student of Léon Cogniet (1794-1880), a respected painter known for both historical subjects and portraiture. Cogniet himself was a product of the Neoclassical tradition, having studied under Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, but his work also showed elements of Romanticism. Studying under Cogniet provided Merle with a solid foundation in academic principles: drawing from the antique and the live model, compositional structure, and the techniques of oil painting suitable for large-scale historical or allegorical works. This rigorous training shaped Merle's technical proficiency and his initial artistic direction.

Debut at the Salon and Early Career

The Paris Salon, the official art exhibition sponsored by the French state and organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the primary venue for artists to display their work, gain recognition, and attract patrons. Making a successful debut at the Salon was a crucial step for any ambitious painter. Hugues Merle achieved this milestone in 1847, exhibiting works including a Self-Portrait (Portrait a l'autotype) and La Legende des Willis, a subject drawn from folklore that would later inspire the ballet Giselle. These initial submissions garnered attention within the art community, marking the beginning of his public career.

The following year, 1848, was tumultuous in France, marked by revolution and the establishment of the Second Republic. While such political upheaval could disrupt artistic life, Merle continued to pursue his career. He participated in the Salon of 1848, exhibiting works such as The Temptation of Saint Anthony (La Tentation de Saint Antoine). His early works often engaged with historical, literary, or religious themes, aligning with the expectations of the academic tradition fostered by teachers like Cogniet and exemplified by established figures such as Paul Delaroche or Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, albeit with a growing sensitivity to emotional portrayal.

Rise to Prominence: The Salon and Recognition

Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, Hugues Merle steadily built his reputation through regular participation in the Paris Salon. His technical skill, combined with his choice of appealing subjects, resonated with the Salon juries and the public alike. He became particularly known for works that explored themes of sentimentality, morality, and domestic virtue, often focusing on the tender bonds between mothers and children or the innocence of youth. This thematic focus distinguished him and proved highly popular in an era that valued art conveying clear emotional or moral messages.

His growing stature was confirmed by official accolades. Merle received Second Class medals at the Salon in both 1861 and 1863, significant honours that acknowledged his artistic merit and standing within the competitive art world. The culmination of this recognition came in 1866 when he was named a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour (Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur), one of France's highest civilian awards. This prestigious decoration solidified his position as a respected member of the French artistic establishment, alongside other decorated Salon painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme or Alexandre Cabanel.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

Hugues Merle's style is firmly rooted in the French Academic tradition, characterized by meticulous draftsmanship, smooth paint surfaces (a high 'fini'), carefully constructed compositions, and an emphasis on idealized human forms. His figures are rendered with anatomical accuracy and often possess a sculptural quality. However, Merle infused this academic framework with a distinct emotional warmth and sensitivity, particularly distinguishing his work from the colder classicism of some predecessors.

His primary thematic concerns revolved around sentiment and morality. He excelled in depicting scenes of maternal love, capturing tender interactions between mothers and their offspring with genuine feeling. Works exploring childhood innocence, often tinged with a gentle melancholy or vulnerability, were also central to his oeuvre. Beyond these domestic scenes, Merle engaged with religious subjects, often choosing moments that emphasized piety, compassion, or biblical narratives with strong emotional cores, such as Reading the Bible. He also drew inspiration from literature, notably creating a well-known interpretation of The Scarlet Letter.

While adhering to academic norms, Merle's work sometimes shows an affinity with aspects of Realism in its detailed observation, particularly in textures and settings, though his figures generally remain idealized rather than showing the unvarnished truth often associated with Gustave Courbet or Jean-François Millet. His careful modulation of light and shadow contributes significantly to the mood and emotional impact of his paintings, highlighting key figures and creating intimate atmospheres.

The Rivalry and Comparison with Bouguereau

It is almost impossible to discuss Hugues Merle without mentioning his contemporary, William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905). The two artists were frequently compared, and often seen as rivals, throughout their careers. Both were masters of the Academic style, both achieved immense popularity at the Salon and with international collectors, and both frequently depicted sentimental themes involving women and children, as well as mythological and religious subjects. Their technical approaches were similar, favouring highly finished surfaces and idealized forms.

Some critics and art historians have suggested that Bouguereau, observing Merle's success with themes of maternal affection, began to explore similar subjects himself, ultimately achieving even greater fame and commercial success in this vein. Whether this constitutes direct influence or simply parallel development within the prevailing tastes of the era is debatable, but the comparison highlights their shared artistic territory. Both artists catered to a market that desired technically brilliant, emotionally accessible, and often idealized representations of beauty, virtue, and sentiment. Their rivalry, whether explicit or perceived, underscores the competitive nature of the Salon system and the specific aesthetic preferences that dominated much of the official art world before the rise of Impressionism.

Key Works and Subject Matter

Several specific paintings exemplify Hugues Merle's style and thematic preoccupations. His interpretation of Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter (exhibited Salon of 1861) captures the somber mood and moral weight of the novel, focusing on Hester Prynne and Pearl. This work demonstrates his ability to translate literary themes into compelling visual narratives, a skill valued within the academic tradition.

Reading the Bible (c. 1860s) is another significant work, depicting a scene of quiet domestic piety. It showcases Merle's skill in rendering intimate interiors and conveying a sense of contemplative spirituality. The careful handling of light and the expressive, yet restrained, figures are characteristic of his approach to religious and moral subjects.

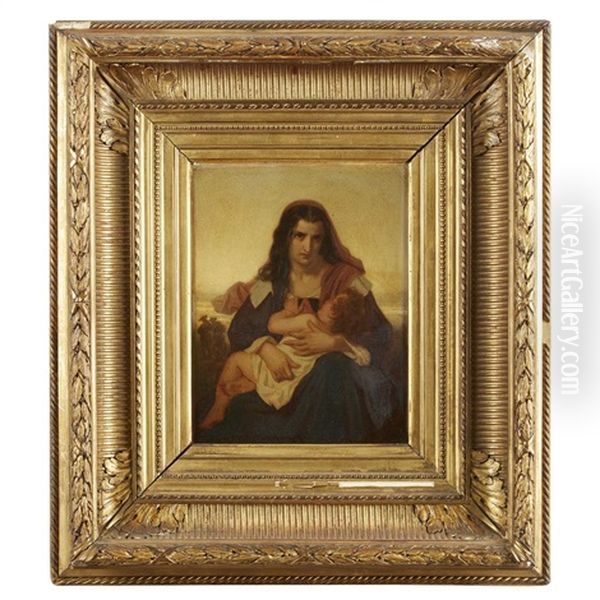

His depictions of maternal love are perhaps his most defining contributions. Works generically titled Mother and Child or carrying titles like Maternal Affection (various dates, including one noted from 1870-71) consistently highlight the tender bond between parent and offspring. These paintings often feature idealized, beautiful figures bathed in soft light, emphasizing purity and devotion. A Neapolitan Girl (Jeune Fille napolitaine, 1876) continues this exploration of feminine grace and youthful innocence, set against a specific cultural backdrop.

The Madonna and Child in a Grotto (1868) represents his engagement with traditional religious iconography, rendered with his characteristic sensitivity and technical polish. Other works mentioned in relation to his career include La Legende des Willis (1847), The Temptation of Saint Anthony (c. 1848), Grape Harvest at Saint-Valérien (possibly early 1850s), and subjects from the Book of Ruth. These works collectively illustrate the range of his subject matter, from folklore and history to literature, religion, and intimate domestic scenes.

The Crucial Role of Paul Durand-Ruel

A significant factor in Hugues Merle's success, particularly in reaching an international audience, was his relationship with the influential art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922). Merle developed a close friendship with Durand-Ruel in the early 1860s, and the dealer became his primary agent. Durand-Ruel was a pioneering figure in the modern art market, known for his innovative strategies, such as providing stipends to artists and organizing solo exhibitions.

Durand-Ruel actively promoted Merle's work, not only in Paris but also abroad, particularly in London and the United States. He bought numerous paintings directly from the artist and facilitated sales to important collectors. Merle even painted portraits of Durand-Ruel and members of his family, cementing their personal and professional connection. This relationship provided Merle with financial stability and exposure beyond the confines of the official Salon system.

Interestingly, Paul Durand-Ruel would later become famous for championing the Impressionists, including artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro, whose style represented a radical departure from the Academic art of Merle and Bouguereau. Merle's association with Durand-Ruel thus places him at a fascinating intersection in art history, connected to a dealer who supported both the established academic tradition and the revolutionary avant-garde.

The American Connection

Hugues Merle's paintings found a particularly receptive audience among American collectors during the Gilded Age (roughly 1870s-1900). Wealthy industrialists and financiers in the United States were actively acquiring European art, often favouring the technical polish and accessible subject matter of French Academic painters. Merle's sentimental themes, particularly his depictions of idealized motherhood and childhood, resonated strongly with Victorian-era American tastes.

Through dealers like Durand-Ruel and potentially others like George A. Lucas (an American agent based in Paris), Merle's works entered prominent American collections. While specific names like Cornelius Vanderbilt and Robert Sterling Clark are sometimes mentioned in the context of collecting Academic art (Clark later founded the Clark Art Institute, known for its Impressionist and Academic holdings), Merle's paintings appealed broadly to this class of patrons. This transatlantic popularity contributed significantly to his financial success and reputation during his lifetime. Today, several important American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., hold works by Hugues Merle, reflecting this historical collecting pattern.

Context and Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Hugues Merle's position, it's helpful to consider him alongside other prominent artists of his time. Within the Academic sphere, besides Bouguereau, key figures included Jean-Léon Gérôme, known for his historical and Orientalist scenes; Alexandre Cabanel, famous for works like The Birth of Venus; and Ernest Meissonier, renowned for his meticulously detailed historical genre paintings. These artists, like Merle, achieved great success through the Salon system and enjoyed state patronage and international acclaim. Their work collectively represents the dominant aesthetic favoured by the official art establishment.

However, Merle's career also coincided with the rise of Realism, spearheaded by Gustave Courbet, who rejected academic idealization in favour of depicting the tangible realities of modern life, often focusing on rural labour or provincial society. Jean-François Millet similarly focused on peasant life, imbuing his subjects with a sense of dignity and monumentality, as seen in The Gleaners. While Merle sometimes depicted genre scenes, his approach remained more idealized and sentimental compared to the often rugged or socially critical realism of Courbet and Millet.

Furthermore, the later part of Merle's career overlapped with the emergence of Impressionism in the 1870s. Artists like Monet, Renoir, Degas, Pissarro, and Berthe Morisot challenged the very foundations of Academic art, prioritizing capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light, and modern urban life with looser brushwork and brighter palettes. While Merle remained committed to his established style, the rise of these avant-garde movements signaled a major shift in artistic values that would eventually eclipse the dominance of Academic painting. Other notable contemporaries included figure painters like Jules Breton, known for his poetic depictions of rural life, and Jules Lefebvre, another successful academic painter of idealized female figures.

Later Years, Family, and Legacy

Hugues Merle continued to paint and exhibit throughout the 1870s, maintaining his focus on the themes that had brought him success. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 and the subsequent Paris Commune undoubtedly impacted life in the capital, but Merle's artistic production seems to have continued relatively uninterrupted. His later works maintained the high level of technical finish and emotional content characteristic of his mature style.

Although Hugues Merle never married, he had a son, Georges Merle (dates uncertain, but active late 19th century), who followed in his father's footsteps and also became a painter. While less famous than his father, Georges Merle's existence points to a continuation of the artistic lineage.

Hugues Merle passed away in Paris on March 16, 1881, at the age of 58. At the time of his death, he was a well-respected and successful artist, decorated by the state and popular with collectors. However, the artistic landscape was rapidly changing. The Impressionists had already held several independent exhibitions, challenging the authority of the Salon, and new artistic movements were on the horizon.

Reassessment and Current Standing

Following his death, and coinciding with the triumph of Modernism (Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, etc.), the reputation of Hugues Merle, along with most Academic painters of the 19th century, declined significantly. For much of the 20th century, Academic art was often dismissed by critics and art historians as conservative, overly sentimental, and lacking in innovation compared to the avant-garde movements. Figures like Merle and Bouguereau were largely relegated to the footnotes of art history, their works often removed from prominent display in museums.

However, beginning in the later 20th century and continuing into the 21st, there has been a significant reassessment of 19th-century Academic art. Art historians began to study these artists within their own historical context, appreciating their technical virtuosity, their engagement with the social and cultural values of their time, and their undeniable popularity and influence during their era. Museums started to re-examine their holdings, leading to exhibitions and publications that shed new light on artists previously overlooked.

Today, Hugues Merle is recognized as a skilled and important representative of French Academic painting. While perhaps still overshadowed by Bouguereau in popular recognition, his work is appreciated for its technical excellence and its sensitive handling of emotional themes. His paintings continue to perform well at auction when they appear on the market, indicating sustained interest among collectors. The presence of his works in major museum collections ensures their accessibility for study and appreciation by new generations. He is remembered as a master of sentiment, whose art provides valuable insight into the aesthetic sensibilities of the 19th century.

Conclusion

Hugues Merle navigated the complex art world of 19th-century France with considerable skill and success. From his rigorous training under Léon Cogniet at the École des Beaux-Arts to his celebrated status as a Salon medalist and Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, his career exemplifies the path to recognition within the Academic system. His focus on themes of maternal love, childhood innocence, morality, and religion, rendered with meticulous technique and genuine emotional sensitivity, struck a chord with the public and patrons of his time, particularly in France and the United States.

Often compared to his contemporary William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Merle developed a distinct artistic voice characterized by delicate execution and poignant subject matter. His relationship with the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel highlights his connection to the burgeoning modern art market. While his reputation waned with the rise of Modernism, recent art historical scholarship has led to a renewed appreciation of his work. Hugues Merle remains a significant figure, a master craftsman whose paintings offer a compelling window into the sentimental heart of the 19th century, embodying both the technical achievements and the prevailing tastes of French Academic art.