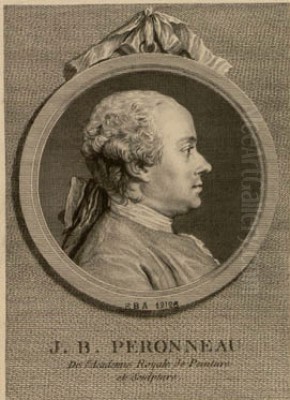

Jean-Baptiste Perronneau stands as one of the most accomplished portraitists of 18th-century France, particularly celebrated for his mastery of the pastel medium. Flourishing during the height of the Rococo era, his work captures the elegance, sensitivity, and psychological nuance of his sitters with a remarkable freshness and immediacy. Though often overshadowed during his lifetime and beyond by his chief rival, Maurice Quentin de La Tour, Perronneau carved a distinct path, creating a body of work admired for its delicate colour harmonies, insightful characterizations, and technical brilliance. His career, marked by extensive travel and a diverse clientele, offers a fascinating window into the artistic and social landscape of Enlightenment Europe.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Jean-Baptiste Perronneau was born in Paris in 1715. His initial artistic training was not in painting but in engraving. He entered the workshop of Laurent Cars, a respected engraver and member of a notable family of printmakers. This early grounding in the precise and linear art of engraving likely honed his skills in draughtsmanship and observation, qualities that would later serve him well in portraiture. Cars himself was well-connected in the Parisian art world, providing young Perronneau with exposure to the prevailing artistic currents.

However, Perronneau's ambitions soon shifted towards painting. He sought further instruction under Charles-Joseph Natoire, a prominent history painter and decorator who played a significant role in the French Rococo movement. Natoire, known for his fluid compositions and light-filled palettes, would have offered a different perspective compared to the graphic discipline of engraving. Studying under Natoire exposed Perronneau to the painterly techniques and aesthetic sensibilities favoured by the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, the dominant art institution in France. This transition from engraving to painting, particularly portraiture, was not uncommon, but Perronneau would bring a unique sensitivity, perhaps informed by his diverse training, to his chosen field.

Emergence as a Portraitist: The Salon and the Académie

The 1740s marked Perronneau's emergence as a professional artist, working in both oil and pastel. Pastel, a medium revived and popularized in France partly through the influence of the Venetian artist Rosalba Carriera earlier in the century, offered a unique combination of vibrant colour and velvety texture, well-suited to capturing the fleeting expressions and delicate complexions favoured in Rococo portraiture. Perronneau quickly demonstrated a remarkable aptitude for this challenging medium.

His public debut came in 1746 when he exhibited several portraits, including pastels, at the prestigious Paris Salon. The Salon, a biennial (later annual) exhibition organized by the Académie Royale, was the primary venue for artists to display their work, gain recognition, and attract commissions. Exhibiting here was crucial for any artist seeking success in the competitive Parisian art market. Perronneau's submissions were generally well-received, drawing attention to his skill and sensitivity.

His growing reputation culminated in his acceptance into the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. He was provisionally accepted (agréé) in 1746 and became a full member (reçu) in 1753. Membership in the Académie was a significant honour, conferring official status and privileges upon an artist. For his reception piece, Perronneau submitted portraits in oil of two fellow artists: the sculptor Jean-Baptiste Pigalle and the painter Jean-Baptiste Oudry (though the Oudry portrait is now lost). This choice of subjects underscored his connection to the artistic community and his competence in the more traditional medium of oil, even as he became increasingly known for his pastels.

Artistic Style: The Subtlety of Pastel

Perronneau's true brilliance lay in his handling of pastels. While he continued to paint in oils throughout his career, his pastels possess a distinct vibrancy, immediacy, and psychological depth that define his unique contribution to French art. He exploited the medium's potential for subtle tonal gradations and rich, yet soft, colour harmonies. His palette often favoured cooler tones – blues, greys, violets, and delicate pinks – applied with a light, feathery touch that suggested rather than explicitly defined form.

Unlike the often more formal and highly finished portraits of some contemporaries, Perronneau's work frequently conveys a sense of intimacy and spontaneity. He excelled at capturing the inner life of his sitters, revealing glimpses of their personality, intelligence, or melancholy through nuanced expressions and attentive gazes. His portraits are rarely stiff or overly posed; instead, they often feel like candid moments observed. He paid meticulous attention to the rendering of fabrics and textures – the sheen of silk, the softness of velvet, the powder on a wig – but always subordinated these details to the overall impression of the sitter's presence.

His style embodies many characteristics of the Rococo aesthetic: elegance, refinement, a focus on sensitivity, and a certain lightness of being. However, it also possesses a strong element of realism and psychological insight that aligns with the Enlightenment's growing interest in individualism and human nature. He avoided the overt flattery sometimes seen in court portraiture, opting instead for a more honest, though always sympathetic, portrayal. This approach particularly resonated with his clientele, which largely consisted of the bourgeoisie, fellow artists, intellectuals, and provincial notables, rather than the highest echelons of the royal court.

The Rivalry with Maurice Quentin de La Tour

No discussion of Perronneau's career is complete without addressing his famous rivalry with Maurice Quentin de La Tour (1704-1788). La Tour was the undisputed king of pastel portraiture in Paris, favoured by King Louis XV, Madame de Pompadour, and the cream of the aristocracy. His studio was a fashionable destination, and his works, often large and brilliantly executed, dominated the Salon exhibitions. La Tour's style was generally bolder, more assertive, and perhaps more overtly virtuosic than Perronneau's more subtle approach.

The competition between the two artists was palpable and played out publicly at the Salons. A notable incident occurred at the Salon of 1750. Both artists exhibited self-portraits in pastel. Contemporary accounts suggest that La Tour, already the established master, may have presented a portrait that made him appear significantly younger, perhaps to subtly assert his seniority and cast Perronneau, who depicted himself more straightforwardly, in the role of a follower. While the exact intentions remain debated by art historians, the episode highlights the intense professional rivalry and the public's fascination with comparing the two leading pastelists.

La Tour's overwhelming success and dominance at court and within the wealthiest circles of Parisian society inevitably impacted Perronneau's career trajectory. While Perronneau received commissions from prominent figures in Paris, he found it challenging to compete directly with La Tour for the most prestigious and lucrative assignments. This professional reality likely contributed significantly to Perronneau's decision to seek patronage outside the capital, leading to his extensive travels throughout France and abroad.

Notable Works and Diverse Sitters

Perronneau's oeuvre includes numerous portraits that exemplify his skill and sensitivity. Among his most celebrated works is Girl with a Kitten (c. 1745), now housed in the National Gallery, London. This charming portrait depicts a young girl, possibly Mademoiselle Huquier, holding a black cat. The composition is intimate and informal, capturing the girl's gentle expression and the cat's wary gaze with remarkable tenderness. The soft lighting, delicate colour palette dominated by blues and pinks, and the masterful rendering of textures make it a quintessential example of Perronneau's art.

Another significant work is the Portrait of Jacques Cazotte (1760-1764), depicting the writer and occultist with an engaging, intelligent expression. The portrait conveys Cazotte's intellectual intensity and perhaps a hint of his mystical inclinations. The Portrait of Olivier Journeu (1756) showcases Perronneau's ability to capture male sitters with sensitivity, depicting the Orléans merchant with a direct gaze and a thoughtful demeanor. He also painted a striking portrait of Charles-François Pinceloup de La Grange (1747), notable for its vibrant blue coat and the sitter's assured presence.

Perronneau's sitters were drawn from various segments of French society, reflecting his broad network of patrons outside the immediate royal circle. He painted fellow artists like the sculptor Pigalle, members of the prosperous bourgeoisie like the Jourdan family of Lyon (for whom he executed several portraits, including Bonaventure and Vivienne Jourdan), provincial administrators, intellectuals, and members of the lesser nobility. This diverse clientele speaks to the appeal of his less formal, more psychologically attuned style to those outside the rigid hierarchies of the court. His ability to connect with and sensitively portray this range of individuals is a testament to his skill and adaptability.

A Peripatetic Career: Travels Across Europe

Frustrated by the intense competition in Paris, particularly from La Tour, Perronneau embarked on a remarkably itinerant career from the 1750s onwards. He spent considerable time working in various French provincial cities, including Orléans, Bordeaux, Toulouse, and Lyon. In these regional centers, he found appreciative patrons among the local elites, merchants, and intellectuals who were eager to be immortalized by a Parisian academician. His travels suggest a pragmatic approach to sustaining his career, actively seeking out markets where his talents were in demand.

His journeys extended far beyond France. He visited Italy, the traditional destination for artists seeking inspiration from classical antiquity and the Renaissance masters, although the specific impact of this trip on his style is not overtly documented. More significantly, he made several trips to the Netherlands, working in Amsterdam and The Hague. The Dutch Republic, with its strong tradition of portraiture dating back to masters like Rembrandt and Frans Hals, offered a different artistic environment and clientele. Perronneau's subtler, more introspective style may have found particular resonance there.

He also traveled to Brussels and reportedly ventured as far as England and even Russia, though details of these latter trips are less certain. This extensive travel was unusual for a French artist of his stature at the time and distinguishes him from many of his contemporaries who remained largely based in Paris. It demonstrates his determination and resourcefulness in building a career across Europe, adapting to different cultural contexts and patronage systems. His final years were spent in Amsterdam, where he ultimately died.

The Artistic Context of 18th-Century France

Perronneau worked during a vibrant and complex period in French art history. The dominant style during much of his career was the Rococo, characterized by its lightness, elegance, intimacy, and often playful or decorative themes. Key figures of the Rococo included François Boucher, known for his mythological scenes and decorative paintings, and Jean-Honoré Fragonard, celebrated for his scenes of love and leisure executed with a dazzlingly fluid technique. Portraitists like Jean-Marc Nattier specialized in idealized depictions of court ladies, often casting them in mythological guise. Perronneau's work shares the Rococo emphasis on sensitivity and refinement but generally avoids its more overtly decorative or frivolous aspects.

The art world was also populated by artists working in different veins. Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, a contemporary Perronneau would have known through the Académie, gained renown for his quiet still lifes and intimate genre scenes, celebrated for their profound observation and masterful technique. While their subject matter differed, both Chardin and Perronneau shared an interest in capturing the truth of their subjects with honesty and sensitivity.

Portraiture itself was a highly competitive field. Besides the dominant La Tour, other skilled portraitists were active, including the Swedish artist Alexander Roslin, who enjoyed considerable success in Paris, and French painters like François-Hubert Drouais (son of the Hubert Drouais Perronneau may have known or been influenced by) and Joseph Ducreux, known for his expressive character studies. Towards the end of Perronneau's life, the artistic tide began to turn away from the Rococo towards the more austere and morally serious style of Neoclassicism, championed by Jacques-Louis David. Furthermore, women artists were gaining increasing prominence, with figures like Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Adélaïde Labille-Guiard becoming celebrated portraitists in their own right, particularly in the years leading up to the French Revolution. Perronneau navigated this dynamic and evolving artistic landscape, maintaining his distinctive focus on pastel portraiture.

Challenges, Criticisms, and Unresolved Questions

Despite his undeniable talent and membership in the Académie, Perronneau's career was not without its challenges. The constant comparison with La Tour, while perhaps stimulating, also limited his opportunities in the lucrative Parisian market. His decision to travel extensively, while necessary for securing commissions, may have also prevented him from building the kind of sustained, high-level patronage base in the capital that La Tour enjoyed.

While generally praised for his skill, his work occasionally faced criticism or nuanced commentary. Some contemporary critics, accustomed to the bolder style of La Tour or the formality of official oil portraiture, may have found Perronneau's delicate touch or psychological subtlety less immediately impressive. There are hints in the source material that his elegant, sometimes sensitive portrayal of male sitters might have occasionally been viewed as bordering on the effeminate or overly refined by some, though concrete contemporary critiques along these lines are scarce. His focus on pastel, while his strength, might also have been perceived by some traditionalists as less prestigious than large-scale history painting or formal oil portraiture, the genres most esteemed by the Académie hierarchy led by figures like Charles-Antoine Coypel or Carle Van Loo earlier in the century.

Even basic biographical details contain minor ambiguities. While his death in Amsterdam in 1783 is established, sources differ slightly on the exact date, citing either November 19th or November 25th. Such discrepancies, though small, reflect the challenges historians sometimes face in reconstructing the lives of artists who operated partly outside the main centers of record-keeping.

Later Life and Death in Amsterdam

Perronneau spent his final years in Amsterdam, a city he had visited previously for work. Why he chose to settle there permanently is not entirely clear, but it suggests he found a welcoming environment and continued opportunities for patronage in the Netherlands. Life as an itinerant artist, constantly moving between cities and countries, may also have taken its toll, prompting him to seek a more stable base in his later years.

Details about his life in Amsterdam during this period are relatively sparse. He continued to work, presumably taking commissions from Dutch clients who appreciated his refined French style. He died there in November 1783, far from his native Paris but in a city that had become a significant locus of his professional life. His death occurred just a few years before the French Revolution would dramatically reshape the artistic landscape he had known.

Legacy and Posthumous Reputation

Following his death, Perronneau's reputation entered a period of relative decline. The rise of Neoclassicism, with its emphasis on heroic themes and classical forms, overshadowed the more intimate and subtle aesthetics of the Rococo. Artists like Perronneau, strongly associated with the pre-Revolutionary era, fell out of critical favour. For much of the 19th century, he remained a secondary figure in accounts of French art, often mentioned primarily in relation to his rival, La Tour. Some of his works were even misattributed over time.

However, a reassessment began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, fueled by a renewed appreciation for 18th-century French art and culture, particularly the Rococo. Critics and collectors, including the influential Goncourt brothers, rediscovered the charm, sensitivity, and technical brilliance of his pastels. Exhibitions dedicated to 18th-century art brought his work back into the public eye.

Today, Jean-Baptiste Perronneau is recognized as a major figure in French Rococo portraiture and one of the preeminent masters of the pastel medium. His works are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Louvre in Paris, the National Gallery in London, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and numerous regional museums throughout France and Europe. His portraits are admired not only for their aesthetic qualities – the delicate handling of colour, the insightful characterizations, the capturing of light and texture – but also as valuable documents of 18th-century society. They offer intimate glimpses into the lives of the artists, intellectuals, and bourgeoisie who shaped the cultural world of the Enlightenment. While he may not have achieved the fame or courtly success of La Tour during his lifetime, Perronneau's unique artistic voice and his mastery of pastel have secured him a lasting and respected place in the history of art. His ability to convey psychological depth with such apparent effortlessness continues to captivate viewers today.