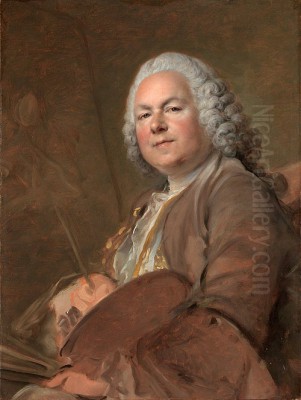

Jean-Marc Nattier (1685-1766) stands as a prominent figure in the glittering world of French Rococo art. A celebrated painter, he became particularly renowned for his exquisite portraits, especially those of the ladies of the French royal court under King Louis XV. His distinctive style often involved depicting his subjects in the guise of figures from classical mythology, blending reality with allegory to create images of enduring grace and charm. His work captured the elegance and refinement of his era, securing his place as a key artist of the 18th century.

An Artistic Heritage

Born in Paris in 1685, Jean-Marc Nattier was immersed in the world of art from his earliest days. His father, Marc Nattier, was a respected portrait painter, providing a direct lineage and likely early instruction in the craft. His mother, Marie Courtois, was a skilled miniature painter, adding another layer of artistic influence within the immediate family. Furthermore, his uncle (often cited as his godfather and teacher), Jean Jouvenet, was a notable history painter. This familial environment undoubtedly nurtured his burgeoning talent.

Nattier received formal instruction under the guidance of his father and his uncle, Jean Jouvenet. He clearly showed precocious ability, as evidenced by winning a prestigious drawing prize from the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) at the young age of fifteen. This early recognition hinted at the successful career that lay ahead. His formal artistic education continued when he enrolled in the Royal Academy in 1703, immersing himself in the official artistic doctrines and practices of the time.

A crucial part of his development involved studying the masters. Nattier spent time at the Luxembourg Palace in Paris, diligently copying the magnificent series of paintings by the Flemish Baroque master Peter Paul Rubens depicting the life of Marie de' Medici. While absorbing lessons from Rubens' dynamic compositions and rich color, Nattier's own style would evolve towards a lighter, more distinctly French sensibility, characteristic of the emerging Rococo aesthetic. He shared his formative years with his brother, Jean-Baptiste Nattier, who also pursued painting, though his life ended tragically.

From History Painting to Fashionable Portraiture

Initially, Nattier aspired to make his name as a history painter, the most esteemed genre within the academic hierarchy of the time. His skills in this area were considerable. He undertook a significant commission from Tsar Peter the Great of Russia, who was visiting Paris, to paint a work depicting the Battle of Poltava. This painting, commemorating a key Russian victory, served as his reception piece for the Royal Academy.

Based on the success of works like this, Nattier was accepted (agréé) into the Royal Academy in 1717 and formally inducted as a full member (académicien) in 1718, initially recognized for his talents in history painting. During Peter the Great's visit to Paris and later during a trip Nattier made to Amsterdam and The Hague in 1717, he also painted portraits of the Tsar, Empress Catherine I, and other members of the Russian court and entourage. Despite receiving an invitation to work in Russia, Nattier ultimately declined, choosing to build his career in his native Paris.

However, the path of a history painter, while prestigious, was not always lucrative. Facing financial difficulties, and likely observing the growing demand for portraiture among the wealthy elite, Nattier strategically shifted his focus. Portrait painting offered more consistent commissions and financial stability. This proved to be a pivotal decision, launching him into the forefront of the Parisian art scene as one of its most sought-after portraitists from the 1730s onwards. He eventually solidified his standing within the Academy, potentially achieving a higher rank or professorship around 1743, reflecting his established success.

The Master of the Mythological Portrait

Nattier's fame rests significantly on his development and popularization of a specific type of portraiture: the portrait historié, or allegorical portrait. He excelled at depicting aristocratic women, particularly those associated with the court of Louis XV, not merely as themselves, but costumed and posed as figures from classical mythology or allegory. This approach flattered his sitters, associating them with timeless ideals of beauty, virtue, and grace embodied by goddesses and muses.

His brush transformed noblewomen into figures like Hebe, the goddess of youth; Flora, the goddess of flowers; or Thalia, the muse of comedy. This blend of portraiture and mythology perfectly suited the Rococo taste for elegance, charm, and playful artifice. The paintings were admired for their idealized beauty, delicate execution, and the skillful way Nattier captured a likeness while simultaneously elevating the subject to a more poetic realm.

Examples of this signature style abound. His portrait of Madame de Bourbon likely depicts a member of the extended royal family in such an allegorical guise. The work titled Thalia, Muse of Comedy, now housed in the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, exemplifies this approach. Similarly, The Spring, held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, uses seasonal allegory to frame the sitter's beauty. He painted Henriette of France (one of Louis XV's daughters) as Flora, a famous example of this genre. Even seemingly straightforward titles often carried these connotations, celebrating the sitter through association with classical ideals.

Court Painter to Louis XV

Nattier's success as a portraitist led him to the highest circles of French society. He became a favorite painter of King Louis XV and the royal family. He was appointed as a court painter, a position that brought immense prestige and a steady stream of commissions from the monarchy and the aristocracy. His ability to capture both a likeness and an air of refined elegance made him particularly popular with the female members of the court.

He painted numerous portraits of Queen Marie Leszczyńska, the Polish-born wife of Louis XV. These portraits, often depicting the Queen in formal attire but with a gentle demeanor, became iconic representations and were widely admired, serving as models for other artists. His relationship with the royal family extended to the King's daughters, known as the Mesdames de France. He painted them frequently, both individually and in groups, often employing his characteristic mythological or allegorical style.

His portrait of Madame Sophie, one of Louis XV's daughters, is a well-known example of his work for the royal family. These commissions cemented Nattier's reputation and placed his work prominently within the opulent interiors of palaces like Versailles. His portraits served not only as records of appearance but also as statements of status, refinement, and the cultivated tastes of the French court during the height of the Rococo period. His portrait of the influential salonnière Madame Geoffrin, now in the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum, shows his reach extended to prominent figures in Parisian cultural life beyond the immediate royal circle.

Artistic Style and Technique

Nattier's style is quintessentially Rococo. It is characterized by elegance, grace, and a certain lightness of touch. His brushwork is refined and delicate, particularly in the rendering of faces and skin, which often have a smooth, porcelain-like finish. He employed a palette typically favoring soft, luminous colors – blues, pinks, yellows, and silvery grays – contributing to the overall charm and decorative quality of his work.

He paid meticulous attention to the depiction of clothing and textiles. The silks, satins, velvets, and lace worn by his aristocratic sitters are rendered with exquisite detail and a convincing sense of texture. This focus on costume was integral to the effect of his portraits, enhancing the sense of luxury and refinement associated with his subjects. Whether depicting contemporary court dress or fanciful mythological attire, the fabrics shimmer and drape convincingly.

While influenced by the richness of Rubens, Nattier adapted these influences to the French taste. His work lacks the robust physicality of the Flemish Baroque, favoring instead a more restrained and delicate elegance. Compared to some of his French contemporaries, his style differs markedly. He did not pursue the intimate domestic realism of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, nor the overtly sensual mythologies of François Boucher, nor the fleeting, poetic scenes of Antoine Watteau's fêtes galantes. Nattier carved his own niche, focusing on idealized portraiture that perfectly captured the sophisticated, albeit somewhat artificial, grace of the French aristocracy. His skill in capturing likeness, even amidst idealization, was noted, though later critics would sometimes find his characterizations less penetrating than those of, for example, the pastel portraitist Maurice Quentin de La Tour.

Collaborations and Connections

The art world of 18th-century Paris was a relatively close-knit community, and Nattier was well-connected. His family background provided initial entry, and his success at the Royal Academy and the Salon solidified his position. The Salon, the official art exhibition organized by the Academy, was a crucial venue for artists to display their work and gain recognition. Nattier regularly exhibited his portraits there, where they were generally received with enthusiasm by critics and the public, further enhancing his fashionable status.

His family connections continued to play a role in his professional life. His daughter, Jeanne-Marie Panier (from his marriage to Marie-Catherine Panier in 1747), married the painter Louis Tocqué. Tocqué was himself a successful portraitist and member of the Royal Academy, known for a somewhat more direct and less idealized style than his father-in-law. There are records suggesting that Nattier and Tocqué occasionally collaborated on works, blending their respective talents.

Nattier's network extended beyond fellow artists to include patrons and influential figures like Madame Geoffrin. His interactions with patrons like Peter the Great and the French royal family were central to his career trajectory. These connections underscore the importance of patronage and social networks in achieving artistic success during this period.

Later Life, Decline, and Legacy

Despite his immense success during the middle decades of the 18th century, Nattier's later years saw a decline in his artistic output and popularity. Fashions in art began to shift, moving away from the Rococo towards the more austere Neoclassical style. Furthermore, Nattier reportedly suffered from health problems that hampered his ability to paint with the same vigor and frequency as before. His production slowed considerably in his final years.

His critical reputation also experienced fluctuations. While celebrated in his heyday, later critics, particularly those embracing Neoclassicism and the more serious tone of the later 18th century, sometimes dismissed his work as charming but superficial, criticizing what they perceived as a repetitive formula and a lack of psychological depth. Some found his color palette, once admired for its delicacy, to be thin or weak. His son, Jean-Baptiste Nattier, also a painter, tragically took his own life, adding a somber note to the family's artistic story.

Jean-Marc Nattier died in Paris in 1766 at the age of 81. Despite the later criticisms, his reputation has since been re-evaluated. Today, he is recognized as one of the defining masters of French Rococo portraiture. His works are appreciated not only for their technical skill and aesthetic charm but also as invaluable historical documents, offering a vivid glimpse into the world of the French aristocracy in the age of Louis XV. His particular brand of mythological portraiture remains his most distinctive contribution.

His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent portraitists, and his paintings continue to be admired in major museum collections worldwide, including the Louvre in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum. His works also appear regularly at auction, attesting to their enduring appeal. Artists like Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, who painted the court of Louis XVI, navigated similar social circles and demands for flattering portraiture, albeit in a later, evolving style. Nattier's legacy is that of an artist who perfectly captured the spirit of his time, blending artistry with social acumen to create a body of work that remains synonymous with the elegance and allure of the French Rococo. Even in the modern era, his distinctive style is recognizable enough to be referenced, as seen in its use as a prompt for AI art generators.

Conclusion

Jean-Marc Nattier was more than just a painter; he was a chronicler of an era. Emerging from an artistic family, he honed his skills under influential teachers like Jean Jouvenet and by studying masters like Rubens. Though initially pursuing history painting, his pragmatic shift to portraiture, driven by economic necessity and market demand, led him to unparalleled success. His unique invention, the portrait historié, which depicted courtly ladies as mythological figures, perfectly captured the Rococo fascination with elegance, artifice, and idealized beauty.

As a favored painter of Louis XV, Queen Marie Leszczyńska, and their daughters, Nattier's brush defined the image of the French court for a generation. His delicate technique, mastery of color and texture, and ability to flatter without losing likeness made him the most fashionable portraitist of his time. While his fame waned in his later years and faced criticism from subsequent generations favoring different aesthetics, his work has earned a lasting place in art history. Today, Jean-Marc Nattier is celebrated as a quintessential Rococo master, whose portraits continue to enchant viewers with their grace, refinement, and evocative portrayal of 18th-century French aristocracy. His paintings remain key works in understanding the visual culture and social aspirations of his time, securing his legacy as a significant figure alongside contemporaries like Boucher, Fragonard, and Watteau.