Jean-Jacques Bachelier (1724-1806) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 18th-century French art. A painter, sculptor, decorative artist, and, crucially, an influential art educator, Bachelier navigated the shifting artistic currents of his time, from the late Rococo to the burgeoning Neoclassical era. His career was marked by prestigious appointments, innovative technical explorations, and a profound commitment to the dissemination of artistic knowledge, leaving an indelible mark on French decorative arts and the very structure of art education in France.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Paris in 1724, Jean-Jacques Bachelier emerged into an artistic world vibrant with creative energy. The French capital was the undisputed center of European art and culture, dominated by the opulent and playful Rococo style. While specific details of his earliest training are somewhat scarce, it is known that he was influenced by artists such as Jean-Baptiste Pâtissier. More significantly, the pervasive influence of masters like Jean-Siméon Chardin, renowned for his intimate still lifes and genre scenes imbued with quiet dignity and masterful handling of texture, would have been part of the artistic atmosphere Bachelier absorbed.

Chardin's meticulous attention to the everyday, his ability to elevate humble objects to subjects of profound artistic contemplation, and his subtle command of light and composition, offered a counterpoint to the more flamboyant tendencies of the Rococo. This grounding in careful observation and technical skill would later manifest in Bachelier's own diverse output, particularly in his celebrated animal paintings and still lifes. His formative years were spent honing his skills in drawing and painting, preparing him for entry into the highly competitive Parisian art scene.

The Royal Academy and Early Career

A pivotal moment in Bachelier's career arrived in 1752 when he was officially received as a member of the prestigious Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture). Membership in the Academy was the primary path to official recognition and state patronage in France. It provided artists with a platform to exhibit their work at the biennial Salons, engage with fellow academicians, and compete for royal commissions. Artists like Charles-Joseph Natoire, then a prominent figure, and François Boucher, a dominant force in the Rococo, were leading lights of the Academy, setting the standards for history painting, mythological scenes, and decorative ensembles.

Initially, Bachelier, like many aspiring academicians, likely focused on history painting, considered the noblest genre. However, his talents soon found expression in other areas. His acceptance piece for the Academy might have demonstrated his proficiency in the prevailing academic standards, but his subsequent career would reveal a remarkable versatility that extended far beyond traditional hierarchies of genre.

A Master of Animal and Still Life Painting

While Bachelier engaged with various subjects, he achieved particular acclaim for his animal paintings and still lifes. He possessed a keen eye for the natural world, capturing the textures of fur and feather, the alert gaze of an animal, or the delicate bloom of a flower with remarkable fidelity and charm.

One of his most famous and enduring works is _White Angora Cat Chasing a Butterfly_ (1761). This painting is a delightful depiction of feline grace and playful instinct. The luxurious white fur of the Angora cat is rendered with exquisite softness, contrasting with the vibrant, delicate wings of the butterfly. The composition is dynamic, capturing a fleeting moment with an elegance that transcends mere animal portraiture. It is often cited as one of the most iconic cat paintings of the 18th century, showcasing Bachelier's sensitivity and technical prowess. This work, and others like _Cat Waiting for a Bird_ and _Cat by a Butterfly_, demonstrate his affinity for these creatures, often portraying them with a personality and vivacity that appealed to contemporary tastes.

Bachelier's skill was not limited to domestic animals. His _Tête de Daim Bizarre_ (Head of a Fallow Deer, 1757) is a striking example of his realistic approach, meticulously detailing the features of the deer's head, complete with a label indicating its origin and date of death, lending it an almost scientific quality. He also painted hunting scenes, such as _Hounds with a Gun and Game Bag_, and depictions of royal pets, like the two paintings of the King's dogs, _Ducuntro and Mimi_. These works placed him in the tradition of esteemed French animal painters such as Alexandre-François Desportes and Jean-Baptiste Oudry, and alongside contemporaries like Jean-Baptiste Huet, who also specialized in pastoral and animal subjects.

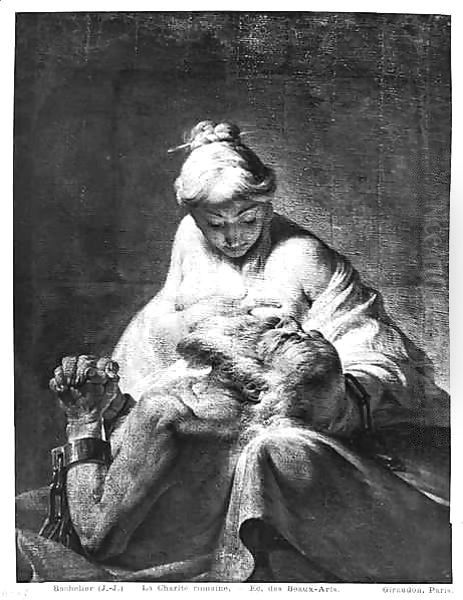

His painting _Roman Charity_ (1765) demonstrates his capabilities in historical and allegorical subjects. The theme, depicting Cimon, an aged prisoner, being secretly breastfed by his daughter Pero to save him from starvation, was a popular one, allowing artists to explore themes of filial piety and compassion. Bachelier's version was notably praised by the influential critic Denis Diderot for the naturalism of its figures, who seemed unconcerned by the viewer's gaze. Diderot, a key figure of the Enlightenment, was a powerful voice in art criticism, and his Salons reviews could make or break an artist's reputation. While he lauded this particular work, Diderot was also known for his sharp critiques, and he did not shy away from pointing out what he perceived as weaknesses in other works by Bachelier, once describing a painting of a drowning child as a "tragic comedy," highlighting the subjective and often exacting standards of the time.

The Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory: A New Direction

A significant turning point in Bachelier's career came in 1757 (some sources state as early as 1748 or 1751 for initial involvement, with directorship from 1757) when he was appointed artistic director of the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory. This royal enterprise, which had evolved from the Vincennes manufactory, was at the forefront of European ceramic production, famed for its luxurious and innovative porcelain. François Boucher had previously provided designs for Vincennes, and his influence on the Rococo aesthetic of Sèvres was profound.

Bachelier's role at Sèvres was transformative. He was tasked with elevating the artistic quality of its productions, moving beyond purely decorative floral patterns to incorporate more sophisticated figural compositions and a wider range of styles. He is credited with introducing and popularizing the use of biscuit porcelain – unglazed, matte-finish porcelain that resembled white marble. This medium was perfectly suited for small sculptures and groups, allowing for a delicacy and subtlety of modeling that was highly prized. Sculptors like Étienne Maurice Falconet created some of their most famous biscuit figures under Bachelier's artistic direction at Sèvres, contributing to the manufactory's international renown.

Bachelier himself designed numerous decorative elements and oversaw the development of new ground colors and gilding techniques. His leadership helped Sèvres navigate the transition from the full-blown Rococo towards the more restrained elegance and classical motifs of the emerging Neoclassical style. He understood the importance of aligning the manufactory's output with the evolving tastes of the court and aristocracy, ensuring its continued success and prestige. His work at Sèvres demonstrates his deep understanding of decorative principles and his ability to apply his artistic talents to a different medium, bridging the gap between fine art and the applied arts.

Innovations in Art and Technique

Beyond his work at Sèvres, Bachelier was an innovator in artistic techniques. He was keenly interested in the materials and methods of painting. He authored a treatise titled _L'Histoire et le secret de la peinture sur la cire_ (The History and Secret of Wax Painting), published in 1755. This work explored the ancient technique of encaustic painting, where pigments are mixed with hot beeswax. This interest brought him into a public dispute with the noted antiquarian and art theorist, the Comte de Caylus, who was also a proponent of reviving encaustic techniques. Such intellectual debates were characteristic of the Enlightenment's spirit of inquiry and rediscovery.

Bachelier also reportedly developed a special beeswax-based varnish intended to protect marble sculptures from the damaging effects of weather. This practical invention underscores his multifaceted engagement with the art world, extending from aesthetic creation to material preservation. These technical explorations highlight a mind that was not only artistic but also scientific and inventive, seeking to expand the possibilities available to artists.

The École Royale Gratuite de Dessin: A Legacy in Education

Perhaps Bachelier's most enduring legacy lies in his contribution to art education. In 1765 (though some sources indicate 1766 for its official letters patent), he founded a free drawing school in Paris, the École Royale Gratuite de Dessin. His vision was revolutionary for its time: to provide free, high-quality instruction in drawing and other arts, particularly to artisans and craftsmen. Bachelier believed that a strong foundation in drawing was essential for improving the quality of French manufactured goods, from textiles and furniture to metalwork and ceramics.

The school's curriculum emphasized geometry and the precise rendering of form, aiming to instill a sense of design and technical proficiency in its students. This initiative was supported by influential figures, including Antoine de Sartine, the Lieutenant General of Police, who understood the economic benefits of a well-trained artisanal workforce. The school was open to students from various backgrounds, offering them opportunities for social and professional advancement.

Bachelier's commitment to accessible education was profound. He even planned to open a similar school for girls in the late 1780s, intending to offer them the same educational opportunities as their male counterparts. Although the French Revolution delayed these plans, the very conception of such an institution was remarkably progressive.

The École Royale Gratuite de Dessin was a resounding success and played a crucial role in the development of French decorative arts. Over time, it evolved, eventually becoming the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs (ENSAD), one of France's most prestigious art and design schools, which continues to thrive today. Bachelier's foresight in establishing this institution had a far-reaching impact, shaping the training of countless artists and designers for generations. His friend, the renowned pastellist Maurice-Quentin de La Tour, was a supporter, and it's suggested Bachelier may have played a role in Pommeroy becoming a director at the school in 1776.

Patronage, Criticism, and Later Years

Throughout his career, Bachelier enjoyed significant patronage. He undertook decorative projects for important royal and aristocratic residences, including the Palace of Versailles and the Château de Maisons. Such commissions were a testament to his standing and his ability to create works that appealed to the sophisticated tastes of the elite.

However, like many artists, he also faced criticism. As mentioned, Diderot's reviews were a mixed bag. While praising certain aspects of his work, Diderot could also be dismissive, reflecting the often-fickle nature of critical opinion and the intense scrutiny under which Salon artists operated. There were also suggestions that, despite his significant contributions, Bachelier was sometimes undervalued or even slighted in his role as head of the École Royale Gratuite de Dessin, perhaps due to the school's practical focus, which some traditional academicians might have viewed as less prestigious than the fine arts training offered by the Royal Academy itself.

The French Revolution (1789-1799) brought profound changes to French society and its artistic institutions. The Royal Academy was abolished, and the system of patronage shifted. Bachelier, by then an established figure, would have witnessed these upheavals. He continued to work and contribute to the art world, adapting to the new realities. His shift from a primary focus on history painting towards more landscapes and animal paintings might also have been influenced by changing market demands and patron preferences over the course of his long career.

Jean-Jacques Bachelier passed away in Paris in 1806, at the age of 82, leaving behind a rich and varied body of work and a transformative educational legacy.

Artistic Style and Influences

Bachelier's artistic style is characterized by its versatility and technical refinement. In his animal paintings and still lifes, he demonstrated a meticulous realism, a sensitivity to texture, and an ability to capture the vital essence of his subjects. These works often possess a charm and intimacy reminiscent of Chardin, though Bachelier's approach could also incorporate the decorative elegance of the Rococo.

His work at Sèvres shows an adaptability to the demands of porcelain design, blending Rococo grace with emerging Neoclassical clarity. He was clearly influenced by the great animaliers like Oudry and Desportes, but he developed his own distinct voice, particularly in his depictions of cats and other domestic animals.

The broader artistic context of his time included the lingering influence of grand manner history painters like Charles Le Brun from an earlier generation, whose organization of the Gobelins manufactory set a precedent for state-sponsored artistic production. In his own era, the Rococo style of artists like Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard was paramount for much of his career, while the more moralizing genre scenes of Jean-Baptiste Greuze gained popularity. Towards the end of his life, the stern Neoclassicism of Jacques-Louis David came to dominate French art, marking a significant stylistic shift from the world in which Bachelier had begun his career. Bachelier's work, in many ways, bridges these periods, incorporating elements of Rococo charm, Enlightenment rationalism, and an early sensitivity to Neoclassical forms.

Bachelier's Enduring Legacy

Jean-Jacques Bachelier's impact on French art is multifaceted. As a painter, he created memorable and beloved images, particularly in the realm of animal and still life painting. His _White Angora Cat Chasing a Butterfly_ remains an iconic work, celebrated for its charm and technical skill.

His contributions to the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory were crucial in maintaining its status as Europe's leading porcelain producer, and his innovations, such as the popularization of biscuit porcelain, had a lasting effect on ceramic art.

However, his most profound and far-reaching legacy is undoubtedly the École Royale Gratuite de Dessin. This institution, born from his vision of accessible and practical art education, transformed the training of artisans and designers in France. Its emphasis on drawing as a foundational skill and its commitment to improving the quality of French decorative arts had a significant economic and cultural impact. The direct lineage from Bachelier's school to the modern ENSAD is a testament to the enduring value of his educational philosophy.

Jean-Jacques Bachelier may not always receive the same level of name recognition as some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, but his dedicated work as an artist, innovator, and educator secured him a vital place in the history of 18th-century French art. He was a man of diverse talents who understood the interconnectedness of art, craft, and industry, and whose efforts significantly enriched the artistic landscape of his nation.