Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard, a name perhaps less immediately recognizable than that of his illustrious father, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, nonetheless carved out a significant, albeit complex, artistic career in a period of profound social and aesthetic upheaval in France. Born on October 26, 1780, in Grasse, and passing away in Paris on November 10, 1850, his life spanned the decline of the Ancien Régime, the turmoil of the French Revolution, the rise and fall of Napoleon, and the subsequent Bourbon Restoration and July Monarchy. As a painter, sculptor, and printmaker, he navigated these shifting tides, his work reflecting the transition from the late Rococo sensibilities of his father to the sterner Neoclassicism and the burgeoning Romanticism of the 19th century.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

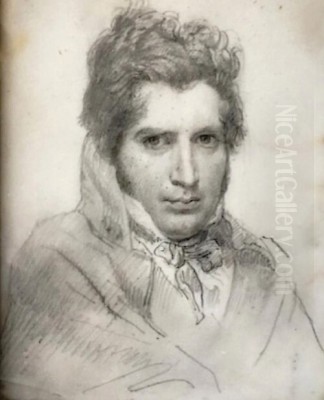

Born into an environment steeped in artistic creation, Alexandre-Évariste was immersed in the world of art from his earliest days. His father, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, was a towering figure of the Rococo movement, renowned for his light-hearted, sensuous, and brilliantly executed scenes of love, leisure, and pastoral idylls. Works like "The Swing" (Les Hasards heureux de l'escarpolette) had defined an era. Young Alexandre-Évariste undoubtedly received his initial instruction from his father, absorbing the technical mastery and fluid brushwork that characterized Jean-Honoré's style. His mother, Marie-Anne Gérard, was also a painter of miniatures, and his aunt, Marguerite Gérard, who lived with the family, was a successful painter in her own right, often collaborating with Jean-Honoré and specializing in intimate genre scenes. This familial artistic crucible provided a rich, if somewhat overwhelming, foundation.

However, the artistic winds were changing. The frivolity of the Rococo was increasingly seen as out of step with the revolutionary fervor and the call for civic virtue. The dominant artistic figure of the era was Jacques-Louis David, the standard-bearer of Neoclassicism. David's powerful, morally charged paintings, such as "The Oath of the Horatii" and "The Death of Marat," emphasized clear lines, sculptural forms, and themes of heroism and sacrifice drawn from classical antiquity. It was to David's studio that Alexandre-Évariste was sent for formal training, a decision that signaled a conscious engagement with the prevailing artistic currents. He reportedly entered David's studio around the age of twelve or thirteen, a testament to his precocious talent.

This dual tutelage—the Rococo grace of his father and the Neoclassical rigor of David—created a fascinating tension in his artistic development. He made his public debut at the Paris Salon of 1793, at the remarkably young age of thirteen, with a painting titled "Timoléon sacrifiant son frère" (Timoleon Sacrificing His Brother). The choice of a subject from Plutarch, depicting a dramatic act of republican virtue, was entirely in keeping with the Neoclassical spirit promoted by David and the revolutionary ethos of the time. This early success brought him to public attention and demonstrated his ambition to engage with serious historical themes.

Artistic Style and Thematic Evolution

Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard's artistic style cannot be easily categorized. While his early training under David instilled Neoclassical principles of composition and subject matter, the influence of his father's Rococo dynamism and painterly approach never entirely vanished. As his career progressed, he also embraced elements of the burgeoning Romantic movement, with its emphasis on emotion, drama, and individualism. This eclectic blend resulted in a unique, if sometimes uneven, artistic output.

His early works, like the aforementioned "Timoleon," clearly show David's influence in their serious subject matter and attempt at clear, didactic storytelling. However, over time, his style often leaned towards a more theatrical and less austere interpretation of historical and literary scenes than that of his master. He developed a penchant for grand compositions, often filled with numerous figures, and a richer, more varied color palette than typically seen in stricter Neoclassical works.

A significant aspect of his oeuvre is his contribution to the "style Troubadour." This genre, popular in France during the early 19th century, particularly during the Bourbon Restoration, focused on idealized scenes from medieval and Renaissance history, often imbued with a sense of chivalry, romance, and national pride. These paintings were characterized by meticulous detail, rich costumes, and often sentimental or anecdotal narratives. Fragonard excelled in this style, producing works that appealed to the contemporary taste for historical nostalgia. Artists like Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret and Fleury François Richard were also prominent figures in this movement, and even the great Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres produced some early works in this vein.

Fragonard's thematic range was broad. He painted large-scale historical subjects, religious scenes, literary illustrations (notably for the works of Ossian, a favorite of the Romantic era), portraits, and genre scenes. He also worked as a sculptor, though his paintings form the bulk of his recognized work. His versatility extended to decorative arts; he provided designs for the Sèvres porcelain manufactory and created decorative panels and ceiling paintings for prominent public buildings, including the Palais Bourbon and the Louvre.

Key Works and Commissions

Throughout his long career, Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard produced a substantial body of work, receiving numerous commissions and exhibiting regularly at the Salon. His "Timoléon sacrifiant son frère" (1793) marked his arrival. Later, works in the Troubadour style gained him considerable recognition.

One notable example is "François Ier armé chevalier par Bayard" (Francis I Knighted by Bayard), a subject that perfectly encapsulated the chivalric ideals of the Troubadour style. Another is "La Leçon d'Henri IV" (The Lesson of Henri IV), depicting the popular king in a moment of paternal instruction, a theme that resonated with the Bourbon Restoration's efforts to evoke the glories of past French monarchs. His painting "Henri IV, Sully, and Gabrielle d'Estrées" (circa 1814) further explored this popular historical period, aligning with the political climate of the Bourbon Restoration.

His historical paintings often depicted dramatic moments, such as "The Triumphant Entry of Joan of Arc into Orléans," a subject that combined national pride with religious fervor, appealing to Romantic sensibilities. Similarly, "Maria Theresa and the Hungarians" showcased a moment of historical drama and royal charisma. His interest in dramatic, almost theatrical compositions is evident in works like "Don Juan et la statue du Commandeur" (Don Juan and the Commander's Statue), which captures the supernatural climax of the famous legend with a Romantic flair.

His work for the Sèvres porcelain manufactory involved creating designs that translated his painterly skills into a different medium, contributing to the factory's prestigious output. His decorative commissions for public buildings, such as ceilings in the Louvre, allowed him to work on a grand scale, often employing allegorical or historical themes suited to the monumental context. These commissions, while perhaps less known today than his easel paintings, were significant markers of his official recognition during his lifetime. He also contributed designs for the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel.

The Shadow of a Famous Father

Living and working under the shadow of a father as famous as Jean-Honoré Fragonard presented both opportunities and challenges for Alexandre-Évariste. The Fragonard name undoubtedly opened doors and provided an initial platform. However, it also invited constant, often unfavorable, comparisons. Jean-Honoré's genius lay in his vibrant, spontaneous brushwork, his exquisite handling of light and color, and his ability to capture fleeting moments of joy and intimacy with unparalleled charm. His style was uniquely his own, a culmination of Rococo aesthetics.

Alexandre-Évariste, by contrast, was an artist of a different era, grappling with different artistic imperatives. While he inherited a degree of his father's facility, his artistic temperament and the stylistic currents of his time led him in other directions. He consciously sought to establish his own identity, moving towards the more "serious" genres of historical and religious painting, perhaps in an attempt to differentiate himself from his father's perceived frivolity, which had fallen out of favor during and after the Revolution. Some accounts suggest he actively sought to distance himself from his father's artistic legacy, preferring not to be seen merely as "Fragonard's son."

Critics and art historians have often noted that Alexandre-Évariste's work, while technically proficient and often ambitious, sometimes lacked the spark, the effortless grace, or the profound emotional depth of his father's best paintings. Where Jean-Honoré's figures seem to breathe with life and sensuality, Alexandre-Évariste's can occasionally appear more staged or academic, a consequence, perhaps, of his Neoclassical training and his engagement with the more formal demands of historical painting. The comparison was, in many ways, an unfair burden, as he was a talented artist in his own right, navigating a complex artistic landscape.

His relationship with his father in later years is not extensively documented, but Jean-Honoré himself faced hardship after the Revolution, as his aristocratic patrons disappeared and his style became unfashionable. He died in 1806, relatively forgotten. Alexandre-Évariste, therefore, had to build his career largely without the active support of a celebrated, currently favored father, relying instead on his own merits and his ability to adapt to the changing tastes of the 19th century.

Connections and Contemporaries

Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard's career unfolded amidst a vibrant and competitive artistic scene in Paris. His training with Jacques-Louis David placed him in the orbit of other prominent artists who emerged from that influential studio. These included Antoine-Jean Gros, known for his dramatic Napoleonic battle scenes; François Gérard, a successful portraitist and historical painter; Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson, whose work often displayed a more Romantic sensibility; and the formidable Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who would become a pillar of 19th-century classicism. While not necessarily close collaborators, these artists were his contemporaries and competitors, shaping the artistic discourse of the time.

His connection with his aunt, Marguerite Gérard, was significant. She was an established artist who had worked closely with his father, Jean-Honoré. Her genre scenes, often depicting intimate domestic interiors with a meticulous finish reminiscent of Dutch Golden Age painters like Gabriël Metsu or Gerard ter Borch, were highly successful. Living in the same household for many years, Alexandre-Évariste would have had ample opportunity for artistic exchange with her, though their styles and primary subjects differed.

In the realm of the Troubadour style, he shared thematic and stylistic concerns with artists like Pierre Révoil, Fleury François Richard, and Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret. They collectively contributed to this nostalgic and picturesque genre. His work also shows an awareness of the broader Romantic movement, which included towering figures like Théodore Géricault, whose "Raft of the Medusa" caused a sensation, and Eugène Delacroix, who would become the leading figure of French Romantic painting. While Fragonard's Romanticism was perhaps more restrained, he shared the era's interest in dramatic narratives, emotional intensity, and historical subjects.

He was also a friend of the landscape and architectural painter Hubert Robert, a contemporary and friend of his father, known for his picturesque views of ruins. Though Robert belonged to an older generation, their paths would have crossed in the Parisian art world. Later in his career, his work might have been known to sculptors like Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, who emerged in the mid-19th century, though direct collaboration is less documented. The artistic world of Paris was relatively concentrated, and artists frequently encountered each other at Salons, academies, and social gatherings.

The influence of earlier masters, beyond his father, is also discernible. The grandeur of Baroque painters like Charles Le Brun, who decorated Versailles for Louis XIV, might have informed his approach to large-scale decorative commissions. The Rococo legacy of Jean-Antoine Watteau and François Boucher, his father's teacher, formed the backdrop against which his own artistic identity was forged, partly in reaction and partly in continuation.

Later Career and Public Reception

Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard maintained a steady presence at the Paris Salon for many decades, from his debut in 1793 until the 1840s. He received numerous state commissions throughout the Napoleonic era, the Bourbon Restoration, and the July Monarchy, indicating a consistent level of official recognition. These commissions included paintings for museums, public buildings, and churches. He was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1819, a significant mark of distinction.

Despite this official success, his critical reception was mixed. While his technical skill was generally acknowledged, some critics found his work to be overly theatrical or lacking in genuine feeling, especially when compared to the raw emotional power of emerging Romantic painters or the austere grandeur of high Neoclassicism. The constant, implicit comparison to his father also colored perceptions of his work. He was often seen as a competent and versatile artist, but not a revolutionary genius in the mold of David, Ingres, Géricault, or Delacroix.

His engagement with the Troubadour style, while popular for a time, eventually saw that genre fade in critical esteem as the 19th century progressed and new artistic movements like Realism, championed by Gustave Courbet, began to take hold. The idealized and often sentimental nature of Troubadour painting came to be seen as somewhat anachronistic.

As he aged, Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard seems to have gradually faded from the forefront of the Parisian art scene. The artistic landscape was continually evolving, and by the mid-19th century, new generations of artists were pushing boundaries in different directions. He continued to work and exhibit, but perhaps without the same prominence he had enjoyed earlier in his career.

Legacy and Historical Reassessment

Upon his death in 1850, Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard was a respected but perhaps not a celebrated figure in the way the leading lights of Romanticism or Neoclassicism were. For much of the later 19th and early 20th centuries, his work, like that of many artists of his transitional generation, was somewhat overlooked. The focus of art historical narratives tended to be on the more clearly defined movements and their most iconic representatives.

However, in more recent decades, there has been a greater appreciation for artists who navigated the complex transitions between major stylistic periods. Art historians have re-examined his oeuvre, recognizing his skill in bridging different artistic currents and his significant contributions to historical painting and the Troubadour style. His ability to adapt to changing tastes and secure consistent patronage across several different political regimes is also noteworthy.

His works are now found in major museum collections, including the Louvre in Paris, the Musée National du Château de Versailles, and various regional museums in France. Exhibitions and scholarly publications have shed more light on his career, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of his place in French art history. He is no longer seen merely as the son of a more famous father, but as an artist who made his own distinct contributions during a dynamic and transformative era.

While he may not have achieved the towering fame of his father or some of his most celebrated contemporaries, Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard's legacy lies in his versatile and prolific output, his role in popularizing the Troubadour style, and his embodiment of the artistic shifts that characterized French art from the late 18th to the mid-19th century. His paintings offer a fascinating window into the tastes, values, and historical imagination of his time. The indirect influence of his family's artistic traditions, particularly the painterly qualities, can even be seen as a distant precursor to the looser brushwork explored by later artists like Edgar Degas or Claude Monet, though this is a more general atmospheric link than a direct line of descent.

Conclusion

Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard's artistic journey was one of navigating a complex inheritance and a rapidly changing world. He successfully forged a career that spanned over half a century, adapting his style and subject matter to the evolving demands of Neoclassicism, Romanticism, and the specific tastes of the Troubadour genre. While the specter of his father, Jean-Honoré, loomed large, Alexandre-Évariste established himself as a distinct artistic personality, a skilled painter and decorator who contributed significantly to the artistic fabric of France during a pivotal period. His works remain a testament to his talent, his adaptability, and the rich, multifaceted artistic currents of his age, offering valuable insights into the cultural and historical landscape of post-revolutionary France.