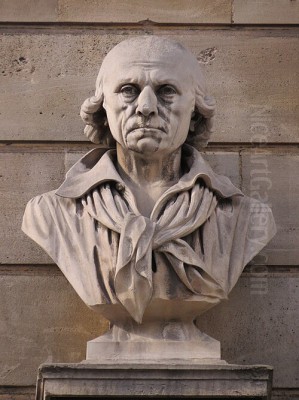

Jean-Jacques-François Le Barbier, born in Rouen on November 11, 1738, and passing away in Paris on May 7, 1826, stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in French art history. Spanning the late Ancien Régime, the tumultuous years of the French Revolution, and the subsequent Napoleonic era and Bourbon Restoration, Le Barbier's career encompassed painting, illustration, and writing. He navigated the shifting artistic and political landscapes of his time, leaving behind a body of work characterized by Neoclassical principles, historical consciousness, and a deep engagement with the ideals of the Enlightenment. While perhaps not possessing the revolutionary fervor of Jacques-Louis David, Le Barbier's contributions, particularly his iconic visualization of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, secure his place as an important visual chronicler of a transformative period in French history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Le Barbier's artistic journey began in his native Rouen, a city with its own rich artistic traditions. He initially studied under Jean-Baptiste Descamps, a painter and writer known for his lives of Flemish, German, and Dutch painters, at the Free School of Drawing in Rouen. This early training likely provided Le Barbier with a solid foundation in drawing and an appreciation for the Northern European artistic heritage. Seeking broader opportunities and more advanced instruction, he eventually made his way to Paris, the undisputed center of the French art world.

In Paris, Le Barbier further honed his skills under the tutelage of Jean-Baptiste-Marie Pierre. Pierre was a prominent history painter, winner of the prestigious Prix de Rome, and eventually became the Premier peintre du Roi (First Painter to the King) and director of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. Studying under Pierre exposed Le Barbier to the highest levels of academic training and the prevailing artistic currents. Although Pierre himself worked in a style that transitioned from late Rococo towards Neoclassicism, the academic environment increasingly championed the burgeoning Neoclassical ideals promoted by figures like Joseph-Marie Vien, who advocated a return to the perceived purity and moral seriousness of classical antiquity.

Le Barbier absorbed these influences, developing a style rooted in clear draughtsmanship, balanced composition, and elevated subject matter. He attempted the Prix de Rome competition, the gateway to studying antiquity firsthand in Italy, though without success. However, he did travel, visiting Switzerland, which likely brought him into contact with the landscapes and perhaps the literary circles that admired nature and sentiment, such as those surrounding the Swiss poet Salomon Gessner, for whom he would later provide illustrations. His formation occurred during a period of stylistic transition, moving away from the lighter, more decorative Rococo style associated with artists like François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard, towards the more austere, didactic, and classically inspired Neoclassicism.

Embracing Neoclassicism and History Painting

By the 1770s and 1780s, Neoclassicism was solidifying its dominance in French art, championed by theorists and artists alike. It was seen as a style appropriate for an age valuing reason, virtue, and public morality, drawing inspiration from the art and perceived values of ancient Greece and Rome. Le Barbier fully embraced this movement, focusing primarily on history painting – considered the noblest genre within the academic hierarchy – as well as mythological and allegorical subjects. His works often carried clear moral or civic messages, aligning with the Enlightenment's emphasis on art's potential to educate and uplift the public.

His acceptance into the prestigious Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in 1785 marked a significant milestone in his career, confirming his status within the official art establishment. His reception piece, typically a requirement for full membership, would have demonstrated his mastery of the Neoclassical style and his ability to handle complex historical or mythological themes. Membership allowed him regular exhibition opportunities at the Paris Salon, the crucial venue for artists to display their work and gain patronage.

Le Barbier's history paintings often depicted scenes intended to inspire virtue, patriotism, or reflection on human conduct. Works like The Courage of the Spartan Women or Hector Reproaching Paris drew on classical narratives to explore themes of duty, sacrifice, and the consequences of personal failings. These subjects resonated with contemporary audiences, who were increasingly interested in historical exemplars of republican virtue, particularly as political tensions mounted in the years leading up to the Revolution. His style, characterized by careful drawing, clear narrative structure, and controlled emotion, fit well within the Neoclassical mainstream, though perhaps lacked the dramatic intensity found in the works of his slightly younger and more famous contemporary, Jacques-Louis David.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

Perhaps Le Barbier's most enduringly famous work is his allegorical representation of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Adopted by the National Constituent Assembly in August 1789, this foundational document of the French Revolution required powerful visual representation to disseminate its principles. Le Barbier's composition, created around 1789-1790 and widely reproduced through engravings (notably by Pierre-Charles Baquoy and Nicolas Ponce), became one of the most iconic images associated with the Declaration.

The painting is rich in symbolism drawn from Enlightenment thought, classical antiquity, and Masonic imagery. It typically depicts the seventeen articles of the Declaration inscribed on two tablets, reminiscent of the Ten Commandments, suggesting a new secular covenant. Presiding over the scene is the Eye of Providence, enclosed within a radiant triangle, symbolizing reason, vigilance, and the deistic Supreme Being often invoked during the Enlightenment, watching over the newly proclaimed rights. Flanking the tablets are allegorical female figures. On the left, a figure representing France breaking the chains of despotism (often holding a scepter or pike topped with a Phrygian cap, symbol of liberty). On the right stands a figure embodying Law or Justice, holding the tablets or pointing towards them.

Other symbolic elements often include the fasces (a bundle of rods bound together, symbolizing unity and authority), laurel wreaths (victory, achievement), and sometimes a serpent biting its tail (the Ouroboros, symbolizing eternity or cyclicality). Le Barbier masterfully synthesized these elements into a harmonious and legible composition that effectively communicated the Declaration's core messages of liberty, equality, popular sovereignty, and the rule of law. This image played a crucial role in popularizing the Revolution's ideals, appearing not only as paintings and prints but also on various artifacts. Its clarity and symbolic richness made it a powerful piece of visual propaganda for the new order.

The Four Continents Tapestries and Political Allegory

Another significant commission undertaken by Le Barbier reflects the intersection of art, politics, and international relations in the late 18th century: the design for a series of tapestries representing The Four Parts of the World (Les Quatres Parties du Monde). Commissioned by King Louis XVI in the late 1780s and woven at the renowned Gobelins Manufactory between 1790 and 1791, this series was intended as a diplomatic gift, possibly for George Washington, though it ultimately remained in France. Le Barbier designed the cartoons, the full-scale paintings used by the weavers.

The series included representations of Europe, Asia, Africa, and America. The design for America is particularly noteworthy for its political commentary. Created in the aftermath of the American Revolutionary War, in which France had played a crucial role supporting the American colonists against Great Britain, the tapestry depicts an allegorical scene celebrating the Franco-American alliance and the birth of the new republic. Rather than focusing solely on American figures or symbols of independence, Le Barbier's composition emphasizes France's role. America is often personified as a figure being aided or protected by Minerva (representing France or wisdom/strategy), sometimes alongside figures representing Liberty and Benjamin Franklin, who was immensely popular in France.

This portrayal reflects the French perspective on the American Revolution, highlighting their contribution and the shared ideals of liberty. It differs significantly from purely American depictions of their struggle. The tapestries demonstrate Le Barbier's skill in translating complex political ideas into grand allegorical compositions suitable for the prestigious medium of tapestry weaving. This commission from the King underscores Le Barbier's standing before the Revolution fully unfolded, capable of undertaking major state-sponsored projects. The changing political climate, however, meant the intended diplomatic purpose was never fulfilled.

A Prolific Illustrator

Beyond his work as a painter of historical and allegorical scenes, Jean-Jacques-François Le Barbier was an exceptionally prolific and highly regarded book illustrator. In an era when illustrated editions of classical texts, contemporary literature, and scientific works were highly prized by collectors and the reading public, Le Barbier's talents were in constant demand. His illustrations graced the pages of numerous deluxe editions, contributing significantly to the aesthetic quality and market success of these publications. It is estimated that he provided designs for illustrations in over sixty different books.

His collaboration with the Swiss poet and painter Salomon Gessner is well-documented. Le Barbier created illustrations for editions of Gessner's popular idyllic works, capturing the sentimental and pastoral mood of the texts. His facility with drawing the human figure, combined with a sensitivity to narrative and emotional nuance, made him adept at translating literary passages into compelling visual scenes. He provided designs that were then translated into engravings by skilled printmakers like Nicolas Ponce, Jean-Michel Moreau le Jeune, and Charles-Nicolas Cochin (though Cochin belonged to an slightly earlier generation, his influence on illustration was profound).

Le Barbier's illustrative work extended to a wide range of authors and subjects. He created designs for editions of classical authors like Ovid (whose Metamorphoses offered rich narrative potential), modern French playwrights like Jean Racine, Enlightenment philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and contemporary poets like Jacques Delille. His illustrations often employed the same Neoclassical stylistic conventions seen in his paintings: clear outlines, idealized figures, dramatic or poignant gestures, and careful attention to historical or mythological detail. This aspect of his career, while perhaps less monumental than his history paintings or tapestries, was crucial to his contemporary reputation and financial success, and demonstrates his versatility as an artist.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Contemporaries

Le Barbier's artistic style remained firmly rooted in Neoclassicism throughout his long career. His primary emphasis was on drawing (dessin), considered the intellectual foundation of art in academic theory. His compositions are generally balanced and clearly organized, prioritizing narrative clarity over dramatic dynamism, although works depicting moments of crisis or heroism naturally incorporate more movement. His figures are often idealized according to classical proportions, though his illustrations sometimes show a greater degree of naturalism or sentiment, perhaps influenced by contemporaries like Jean-Baptiste Greuze, known for his moralizing genre scenes.

His thematic concerns revolved around history (both ancient and contemporary), mythology, allegory, and the illustration of literature. A recurring interest was the exploration of civic virtue, heroism, and moral dilemmas, reflecting the didactic preoccupations of the Enlightenment and the Revolutionary era. Works like the painting depicting the heroic self-sacrifice of André Desilles during the Nancy Mutiny (1790), which Le Barbier worked on in 1794 and exhibited later in 1819, exemplify this focus on contemporary events imbued with classical notions of virtue. Later works, such as A Canadian Mother Mourning the Death of Her Child (exhibited 1817), suggest an engagement with themes of universal human emotion, perhaps touched by the emerging sensibilities of Romanticism.

Le Barbier worked within a vibrant and competitive Parisian art world. He exhibited alongside major figures at the Salon. These included the undisputed leader of Neoclassicism, Jacques-Louis David, whose politically charged works like The Oath of the Horatii set a powerful standard. Other contemporaries included history painters like François-André Vincent and Joseph-Benoît Suvée; the portraitist Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, famous for her depictions of Queen Marie Antoinette; landscape and ruin painters like Hubert Robert; and artists who bridged Neoclassicism and early Romanticism, such as Pierre-Paul Prud'hon. Le Barbier would also have known the next generation emerging from David's studio, including Anne-Louis Girodet, Antoine-Jean Gros, and François Gérard, and later, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who would carry Neoclassical principles into the 19th century. Le Barbier navigated this complex scene, maintaining a consistent, if perhaps less groundbreaking, artistic path.

Later Career, Writings, and Legacy

Le Barbier continued to work and exhibit through the Napoleonic Empire and the Bourbon Restoration. While the grand historical and allegorical commissions of the pre-Revolutionary and Revolutionary periods may have become less frequent, he remained active, particularly as an illustrator. He also turned his hand to writing, publishing works on artistic theory and practice, such as Principes de dessin d'après nature (Principles of Drawing from Nature) and essays on subjects like the beauty of women, demonstrating the intellectual breadth common among artists of his era.

Despite his productivity, Academy membership, and the enduring fame of his Declaration illustration, Le Barbier's reputation in art history has often been overshadowed by more dominant figures like David or later Romantic painters. Some critics, both contemporary and later, found his style somewhat conventional or lacking in powerful innovation compared to the dramatic intensity or political edge of some of his peers. His adherence to established Neoclassical norms might have made his work seem less revolutionary in retrospect.

However, this assessment perhaps undervalues his specific contributions. His visualization of the Declaration of the Rights of Man remains a potent and instantly recognizable symbol of the French Revolution and its ideals, reproduced countless times and serving as a key piece of historical iconography. His designs for the Four Continents tapestries offer valuable insight into the political uses of art and the Franco-American relationship in the late 18th century. Furthermore, his extensive work as an illustrator highlights his skill and versatility, contributing significantly to the rich tradition of French book art during a golden age of publication.

Conclusion: A Versatile Artist in a Time of Change

Jean-Jacques-François Le Barbier was a versatile and highly productive artist whose career successfully navigated one of the most turbulent periods in French history. Trained in the academic tradition and fully embracing the Neoclassical style, he created significant works in history painting, allegory, and tapestry design. His iconic representation of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen cemented his place in the visual culture of the French Revolution. Simultaneously, his prolific output as a book illustrator demonstrates another crucial dimension of his artistic practice, showcasing his narrative skill and draughtsmanship across a wide range of literary subjects.

While perhaps lacking the transformative impact of a figure like Jacques-Louis David, Le Barbier was a respected member of the artistic establishment, adept at fulfilling major commissions and contributing thoughtfully to the visual discourse of his time. His work consistently reflects the Enlightenment's emphasis on reason, morality, and civic virtue, rendered in the clear, ordered language of Neoclassicism. As a painter, illustrator, and writer, Jean-Jacques-François Le Barbier offers a valuable perspective on the artistic culture of late 18th and early 19th century France, an artist whose work captured the ideals, aspirations, and historical consciousness of an era of profound change. His legacy endures, particularly through the powerful symbolism embedded in his depiction of human rights, a testament to art's ability to give form to foundational political ideas.