Jacques-Louis David stands as one of the most influential figures in the history of Western art. As the preeminent painter of the Neoclassical era, his work not only defined the style but also became inextricably linked with the turbulent political landscape of late 18th and early 19th century France. His career spanned the final years of the Ancien Régime, the entirety of the French Revolution, and the rise and fall of Napoleon Bonaparte. David was more than an artist; he was a political activist, a propagandist, a teacher, and a cultural dictator whose influence shaped the artistic tastes of a generation and visually chronicled an era of profound transformation.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Jacques-Louis David was born in Paris on August 30, 1748, into a prosperous bourgeois family. His father, Louis-Maurice David, was an iron merchant, and his mother, Marie-Geneviève Buron, came from a family of builders and architects. This connection to the building trades perhaps initially steered the family's ambitions for the young Jacques-Louis towards architecture.

Tragedy struck early in David's life. When he was just nine years old, his father was killed in a duel. His mother subsequently left him in the care of his uncles, François Buron and Jacques-François Desmaisons, both successful architects. They provided him with an excellent education at the Collège des Quatre-Nations, but David proved to be an indifferent student, often filling his notebooks with drawings. A facial tumor, possibly the result of a fencing injury, developed during this time, slightly impeding his speech but perhaps intensifying his reliance on visual expression.

Recognizing his artistic inclinations, his uncles, despite their initial hopes for an architectural career, eventually relented. They sought advice from François Boucher, the leading Rococo painter of the day and a distant relative. Boucher, however, sensing the changing artistic tides and perhaps recognizing David's more severe temperament, declined to take him on directly. Instead, he recommended David to Joseph-Marie Vien, another prominent painter who worked in a more classical, albeit still somewhat Rococo-inflected, style.

Academic Training and the Lure of Rome

In 1766, David entered the studio of Vien and enrolled at the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture). The Académie was the dominant institution in French art, controlling training, exhibitions (the Salons), and prestigious commissions. The ultimate prize for an aspiring history painter was the Prix de Rome, a scholarship allowing winners to study for several years at the French Academy in Rome.

David's path to the Prix de Rome was fraught with frustration. He competed several times, feeling unfairly judged by the Académie establishment, which still favored the lighter Rococo aesthetic. His early submissions, while technically proficient, perhaps lacked the full conviction of his later style. He failed in 1771, 1772 (leading to a reported suicide attempt through starvation), and 1773. This period of rejection likely fueled his later antagonism towards the Académie system.

Finally, in 1774, David achieved his goal, winning the Prix de Rome with his painting Erasistratus Discovering the Cause of Antiochus' Disease. This victory was a turning point. Accompanied by his mentor Vien, who had just been appointed director of the French Academy in Rome, David traveled to Italy in 1775. The five years he spent there were transformative.

The Roman Crucible and the Birth of Neoclassicism

Rome exposed David to the art he had only known through prints and copies. He immersed himself in the study of ancient Roman sculpture and architecture, visiting the ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum, and filling sketchbooks with drawings. He also deeply admired the masters of the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods, particularly Raphael, Michelangelo, and Caravaggio, whose dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) would profoundly influence him.

Crucially, Rome was also the intellectual center of the burgeoning Neoclassical movement. David encountered the ideas of art theorists like Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who championed the "noble simplicity and calm grandeur" of Greek art, and painters like the German Anton Raphael Mengs, who were already pioneering a return to classical principles. This environment solidified David's rejection of the perceived frivolity and artificiality of the Rococo style epitomized by Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

He began to forge a new aesthetic: severe, rational, didactic, and morally uplifting. His drawing became crisper, his compositions more ordered and planar (often resembling classical friezes), his colors more sober, and his subject matter increasingly drawn from classical history and literature, chosen for its exemplary virtues. Early works from this period, like The Funeral of Patroclus (1778), show this evolving style. Upon his return to Paris in 1780, David was armed with a new artistic vision and the ambition to reshape French painting.

Breakthroughs and Masterpieces

David's return to Paris marked the beginning of his ascent. He was quickly accepted as an associate member of the Académie Royale in 1781 upon presentation of his painting Belisarius Begging for Alms. This work, depicting the unjustly disgraced Byzantine general, already showcased his Neoclassical style and his interest in themes of stoicism and virtue, resonating with Enlightenment ideals.

His marriage in 1782 to Marguerite Charlotte Pécoul, the daughter of a wealthy building contractor and superintendent of buildings, brought him considerable financial security and social standing. This stability allowed him greater freedom in pursuing his artistic goals. They would eventually have four children.

The painting that definitively established David as the leader of the Neoclassical school was The Oath of the Horatii, completed in Rome in 1784 and exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1785. Commissioned by the Crown, the painting depicts a scene from early Roman history where three brothers swear an oath to their father to fight to the death for Rome. Its stark composition, sculptural figures, dramatic lighting, and powerful theme of patriotic self-sacrifice caused a sensation. It was hailed as a manifesto of the new style, a call for moral rigor and civic virtue that contrasted sharply with the perceived decadence of the court.

David followed this triumph with other major works that solidified his reputation. The Death of Socrates (1787) portrayed the philosopher's calm acceptance of his unjust death sentence, celebrating reason and principled defiance. It further cemented David's position as the foremost history painter in France, admired for both his technical mastery and the intellectual weight of his subjects.

Another significant work from this pre-revolutionary period was The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons (1789). Depicting the Roman consul who condemned his own sons to death for treason, the painting explored the painful conflict between personal feeling and civic duty. Exhibited shortly after the storming of the Bastille, it acquired immediate political resonance in the charged atmosphere of revolutionary Paris.

Artist of the Revolution

As the French Revolution erupted in 1789, David embraced its cause with fervor. His Neoclassical ideals – emphasizing reason, virtue, and sacrifice for the state – aligned perfectly with the Revolution's rhetoric. He quickly became one of its most prominent artistic voices and an active political participant.

He joined the radical Jacobin Club and was elected as a deputy to the National Convention in 1792, where he voted for the execution of King Louis XVI. David served on influential committees, including the Committee of Public Instruction and the Committee of General Security. He used his position to attack the old artistic establishment, playing a key role in the abolition of the Académie Royale in 1793, which he viewed as elitist and resistant to change.

David effectively became the Revolution's chief propagandist and master of ceremonies. He designed revolutionary festivals, costumes, and symbols, seeking to create a new visual culture for the Republic. His art directly served the revolutionary cause. He began work on The Tennis Court Oath (1791), a massive, unfinished canvas commissioned to commemorate the pivotal moment when the Third Estate vowed not to disband until a constitution was established. Though never completed, the preparatory drawings reveal his ambition to create a modern history painting capturing the collective will of the people.

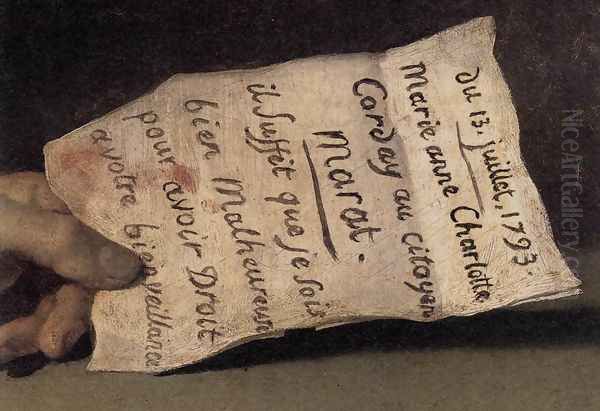

His most iconic revolutionary painting is The Death of Marat (1793). Jean-Paul Marat, a radical journalist and friend of David's, was assassinated in his bath by Charlotte Corday. David was called upon to depict the scene and create a martyr for the Revolution. He portrayed Marat with stark realism yet imbued the scene with a quiet dignity and pathos reminiscent of religious depictions of Christ's deposition. The painting, with its simple composition, dramatic lighting, and poignant detail, became an enduring image of revolutionary sacrifice. He also painted a portrait of the deputy Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau on his deathbed, another revolutionary martyr, though this work was later destroyed.

David's deep involvement with the Jacobins, particularly his association with Maximilien Robespierre, put him in danger during the Thermidorian Reaction that followed Robespierre's fall in 1794. He was arrested and imprisoned twice. His wife, Marguerite Charlotte, a staunch royalist, had divorced him earlier due to his radicalism. However, she reportedly worked for his release during his imprisonment, and they remarried in 1796 after he was freed. During his confinement, he painted his only landscape, the serene View of the Luxembourg Gardens.

Painter to the Emperor

Emerging from prison, David found a changed political landscape. The Directory period was unstable, and David initially retreated somewhat from overt political engagement in his art, focusing on themes from classical mythology, such as The Intervention of the Sabine Women (1799), a plea for reconciliation after the Reign of Terror.

However, the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte offered David a new focus and a powerful patron. David admired Napoleon, seeing him as a heroic figure who could restore order and embody the Revolution's positive achievements. Napoleon, in turn, recognized the power of David's art for propaganda and consolidating his own image and legitimacy.

David met Napoleon in 1797 and was immediately captivated. He began planning a grand portrait, Napoleon Crossing the Alps (or Bonaparte at the Saint-Bernard Pass), completed between 1801 and 1805. This highly idealized image, depicting Napoleon calmly leading his army across the treacherous pass, became one of the most famous equestrian portraits in history. David produced several versions of this potent piece of propaganda.

When Napoleon declared himself Emperor in 1804, he appointed David as his Premier Peintre (First Painter). David's studio became the official source for Napoleonic imagery. His most ambitious undertaking for the Emperor was the colossal Coronation of Napoleon (1805-1807). Measuring over 33 feet wide, this meticulously detailed painting depicts the opulent ceremony in Notre Dame Cathedral where Napoleon crowned himself and Empress Josephine. David took liberties with the scene, notably adding Napoleon's mother, Letizia, who was not actually present, to please the Emperor.

Other major works from the Napoleonic period include The Distribution of the Eagle Standards (1810), celebrating the army's loyalty, and numerous portraits of Napoleon, his family, and members of the imperial court. David's style during this period retained its Neoclassical clarity but often incorporated a greater richness of color and texture, reflecting the grandeur and pageantry of the Empire.

The Master's Studio: Teaching and Influence

Throughout his career, David was a highly influential teacher. His studio was the most prestigious and sought-after in Paris, attracting hundreds of students from France and across Europe. He dominated French art education, particularly after the abolition of the old Académie.

David's teaching methods emphasized rigorous drawing, close study of classical sculpture, and meticulous observation of the live model. He believed that mastery of form was the foundation of great art. While demanding, he also fostered a sense of camaraderie and intellectual debate among his pupils. His studio was not just a place of technical instruction but also a hub of artistic and sometimes political discussion.

He trained many of the leading artists of the next generation. Among his most famous pupils were:

Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835): Known for his dramatic paintings of Napoleonic battles, Gros bridged the gap between Neoclassicism and the emerging Romantic movement.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867): While deeply influenced by David's emphasis on line, Ingres developed his own distinct, highly refined style and became the leading figure of French Neoclassicism after David's exile. Their relationship was complex, marked by both admiration and rivalry.

Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (1767-1824): Often known simply as Girodet, he developed a more personal and often sensual style that prefigured Romanticism.

François Gérard (1770-1837): A successful portraitist and history painter favored by the Napoleonic court and later the Bourbon monarchy.

Jean-Germain Drouais (1763-1788): A highly promising student who won the Prix de Rome but died young in Italy.

Jean-Baptiste Isabey (1767-1855): A renowned portrait miniaturist.

David's influence extended far beyond his direct pupils, shaping the course of academic painting in France and elsewhere for decades. His emphasis on historical subjects, moral purpose, and formal clarity set the standard against which subsequent artistic movements, including Romanticism, would react.

Exile and Final Years

The fall of Napoleon in 1815 marked the end of David's dominance in France. With the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy under Louis XVIII, David, as a regicide (having voted for Louis XVI's execution) and a prominent Bonapartist, was targeted. Although offered amnesty by the new king, perhaps partly due to the influence of former students like Gérard, David chose self-imposed exile.

In 1816, he settled in Brussels, in what was then the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. He was welcomed by the artistic community there and continued to paint and receive commissions, primarily portraits and mythological subjects. His style in exile remained technically brilliant, but some critics find his later mythological works, such as Cupid and Psyche (1817) and Mars Being Disarmed by Venus and the Three Graces (1824), lack the revolutionary fervor and political edge of his earlier masterpieces. They possess a cooler, more detached quality, sometimes with a heightened sensuality.

Despite being exiled, David remained a revered figure, and his studio in Brussels continued to attract students. He maintained contact with his former pupils in Paris, including Gros and Gérard. He refused invitations to return to France, remaining in Brussels until his death.

Jacques-Louis David died in Brussels on December 29, 1825, after being struck by a carriage. The Bourbon government refused to allow his body to be returned to France for burial. He was interred in Brussels, though his heart was later entombed at the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Legacy of a Revolutionary Artist

Jacques-Louis David's legacy is immense and complex. He was the undisputed master of Neoclassicism, defining its aesthetic principles and producing its most iconic works. His paintings, from The Oath of the Horatii to The Death of Marat and The Coronation of Napoleon, are landmarks of art history, admired for their formal rigor, technical brilliance, and powerful engagement with their historical moment.

He demonstrated that art could be a potent political force, shaping public opinion and serving the state. His career mirrored the tumultuous changes in French society, from the ideals of the Enlightenment through the fervor of the Revolution to the autocratic grandeur of the Napoleonic Empire.

As a teacher, he shaped a generation of artists, ensuring the continuation of the classical tradition even as new movements began to challenge it. His influence was felt throughout Europe, making Neoclassicism the dominant international style for decades.

While his unwavering political commitments led to controversy and ultimately exile, they were inseparable from his artistic vision. David believed art should serve a higher moral and civic purpose. Whether depicting Roman heroes, revolutionary martyrs, or an Emperor, he sought to inspire virtue, patriotism, and awe through the clarity and severity of his Neoclassical style. He remains a pivotal figure, embodying the profound connections between art, politics, and history during an age of revolution.