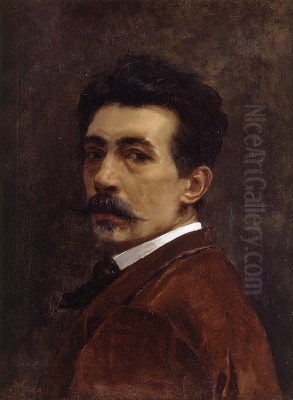

Joaquín Agrasot y Juan stands as a significant figure in nineteenth-century Spanish art, particularly renowned for his contributions to the Valencian school of painting. Born in Orihuela in 1836 and passing away in Valencia in 1919, Agrasot carved a niche for himself through his vivid depictions of Spanish life, his mastery of light and color, and his close association with the influential artist Mariano Fortuny y Marsal. His work, primarily falling under the umbrella of Costumbrismo, offers a rich tapestry of regional customs, landscapes, and the everyday moments of the Spanish people, rendered with a technique that absorbed both academic tradition and contemporary innovations.

Agrasot's long life spanned a period of significant change in Spain and Europe, witnessing the evolution of artistic styles from Romanticism and Realism towards Impressionism and beyond. While not strictly adhering to any single avant-garde movement, his art reflects the artistic currents of his time, particularly the fascination with genre scenes, the impact of realism, and a profound interest in the effects of light, which would become a hallmark of Valencian painting. His legacy is that of a dedicated chronicler of his culture and a painter of considerable technical skill whose works continue to be appreciated for their vibrancy and authenticity.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Valencia

Joaquín Agrasot y Juan was born on December 24, 1836, in Orihuela, a town in the province of Alicante, part of the Valencian Community in Spain. His early artistic inclinations led him to Valencia, the regional capital and a burgeoning center for arts and culture. There, he enrolled in the prestigious Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Carlos, one of Spain's leading art academies. This institution provided him with a solid foundation in academic principles, emphasizing drawing, composition, and the study of Old Masters.

During his formative years at the Academy, Agrasot studied under the guidance of D. Francisco Martínez Yago, a respected Valencian painter and educator. Martínez Yago (1814-1895) would have instilled in his pupil the importance of rigorous draftsmanship and the traditional techniques valued by the academic system. This training was crucial, providing Agrasot with the technical proficiency that would underpin his later stylistic developments. The artistic environment in Valencia, with its rich cultural heritage and growing community of artists, undoubtedly played a role in shaping his early artistic vision.

His talent was recognized early on, leading to opportunities for further development. Like many promising Spanish artists of his generation, the path to greater recognition often led through further studies, particularly in Rome, the historical epicenter of European art. Agrasot secured the means to travel to Italy, a journey that would prove pivotal in his artistic career, exposing him to new influences and connecting him with a vibrant international community of artists.

The Roman Sojourn and the Encounter with Fortuny

Rome in the mid-nineteenth century was a magnet for artists from across Europe and America. It offered not only the chance to study classical antiquity and Renaissance masterpieces firsthand but also a lively contemporary art scene. For Spanish artists, obtaining a 'pensionado' (a state-funded scholarship) to study in Rome was a mark of distinction and a critical step towards establishing a successful career. Agrasot spent a significant period in Italy, immersing himself in its artistic treasures and, crucially, connecting with fellow artists.

The most consequential encounter during his time in Italy was with Mariano Fortuny y Marsal (1838-1874). Fortuny, though only slightly younger than Agrasot, was already becoming a phenomenon in the European art world. Hailing from Catalonia, Fortuny possessed an extraordinary technical virtuosity, characterized by dazzling brushwork, a brilliant sense of color, and an ability to capture light with remarkable intensity. His small-scale, highly detailed paintings, often depicting historical genre scenes or exotic Orientalist subjects, were immensely popular and commanded high prices, particularly through influential dealers like Adolphe Goupil in Paris.

Agrasot fell into Fortuny's orbit, becoming a close friend and admirer. He joined the circle of Spanish artists who gathered around Fortuny in Rome, a group that included other talented painters such as Martín Rico y Ortega (1833-1908), a gifted landscape painter, and Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta (1841-1920), Fortuny's brother-in-law and another highly successful genre painter. This association was profoundly influential for Agrasot, exposing him directly to Fortuny's innovative techniques and his approach to subject matter.

The relationship was one of mutual respect and camaraderie. They spent considerable time together, painting, discussing art, and traveling. Records indicate that Agrasot, Fortuny, and Martín Rico traveled together in Spain, visiting Seville and Granada in 1871. Granada, with its Moorish architecture and vibrant culture, held a particular fascination for Fortuny and his circle. Later, during the summer of 1874, shortly before Fortuny's untimely death, Agrasot was part of the group of friends staying with him at a villa in Portici, near Naples. This close personal and professional connection left an indelible mark on Agrasot's artistic development.

The Influence of Fortunyism

The term 'Fortunyism' is often used to describe the style and influence exerted by Mariano Fortuny on his contemporaries. It wasn't a formal movement but rather a shared aesthetic characterized by brilliant light effects, jewel-like colors, meticulous detail rendered with seemingly effortless, sparkling brushwork (known as preciosismo), and a preference for genre, historical, or Orientalist themes presented in an engaging, often anecdotal manner. Fortuny's international success made his style highly sought after and widely imitated.

Joaquín Agrasot absorbed many aspects of Fortuny's approach. His palette brightened considerably, and he developed a keen interest in capturing the intense Mediterranean sunlight and its effects on surfaces and figures. The meticulous attention to detail, particularly in rendering textures, fabrics, and architectural elements, also reflects Fortuny's influence. Agrasot learned from Fortuny's innovative techniques, adapting them to his own artistic temperament and subject matter.

However, Agrasot was not merely an imitator. While Fortuny often favored exotic locales or historical reconstructions, Agrasot primarily focused his lens on contemporary Spanish life, especially the rural customs and people of his native Valencia region. He translated the brilliance and technical facility of Fortunyism into a distinctly Spanish idiom, applying it to scenes of local peasants, village gatherings, and everyday labor. This adaptation allowed him to create works that resonated with a sense of national identity while employing a modern, internationally recognized technique.

Furthermore, Agrasot played a role in disseminating Fortuny's practical innovations. It is noted that around 1875, after Fortuny's death, Agrasot introduced a small, portable easel invented by Fortuny to other artists. This type of easel was particularly useful for painting outdoors (plein air), demonstrating the practical and technical exchanges within their circle. The influence was thus multifaceted, encompassing style, technique, subject approach, and even the tools of the trade.

Master of Costumbrismo

Agrasot's primary contribution lies within the genre of Costumbrismo. This Spanish artistic and literary movement, particularly popular in the 19th century, focused on depicting the everyday life, manners, customs, and types ('tipos') of a particular region or the country as a whole. It was closely related to Realism but often carried a picturesque or anecdotal flavor, celebrating local identity and traditions in a rapidly changing world.

Agrasot excelled in this genre, becoming one of the leading Costumbrista painters of the Valencian school. His canvases are populated with scenes drawn directly from the life around him: farmers working in the fields, women washing clothes by the river, families gathered in rustic interiors, lively village fiestas, and characteristic local figures like musicians or tradespeople. He approached these subjects with an eye for detail and a sense of empathy, capturing the textures of rural life – the rough fabrics of peasant clothing, the sun-baked walls of village houses, the tools of labor, the gestures and expressions of the people.

His paintings often present typical compositions associated with the genre, such as scenes set in village squares or courtyards, providing a stage for social interaction and the display of local customs. Works like Valencian Couple or scenes depicting local markets showcase his ability to orchestrate multi-figure compositions while maintaining a focus on individual characterization and authentic detail. These works served not only as artistic expressions but also as valuable visual documents of Valencian culture in the late 19th century.

The influence of his Italian stay and his connection with Fortuny enriched his Costumbrista works. He infused the often earthy realism of the genre with a brighter palette and a more sophisticated handling of light, elevating the everyday scenes beyond mere documentation to become vibrant artistic statements. This blend of local subject matter with advanced technique distinguishes Agrasot's contribution to Spanish Costumbrismo.

Capturing the Mediterranean Light

A defining characteristic of Agrasot's art is his fascination with light. Valencia, situated on the Mediterranean coast, is bathed in a unique, intense sunlight, and capturing its effects became a central preoccupation for many artists from the region. Agrasot was among the pioneers in exploring the expressive potential of this light, prefiguring the later, more famous Valencian Luminist movement led by Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863-1923).

In Agrasot's paintings, light is often a protagonist. He skillfully depicted the play of bright sunlight and deep shadow, using contrasts to define form and create atmosphere. His outdoor scenes frequently feature the dazzling glare of the midday sun, bleaching colors and casting sharp shadows. Interior scenes are often illuminated by strong light streaming through windows or doorways, highlighting textures and creating dramatic focal points. A characteristic golden tonality often pervades his work, perhaps reflecting the warm Mediterranean light or even the influence of Italian painting traditions.

His handling of light goes beyond mere representation; it contributes significantly to the mood and narrative of his paintings. Whether depicting the cheerful bustle of a village festival under a bright sky or the quiet intimacy of a sunlit domestic interior, Agrasot used light to enhance the emotional resonance of the scene. This focus on luminosity connects him to a broader European interest in light effects during the latter half of the 19th century, but his interpretation remained firmly rooted in his specific Valencian environment.

While Sorolla would later take the exploration of Valencian light to new heights with his looser brushwork and Impressionist influences, Agrasot's earlier achievements laid important groundwork. His dedication to observing and rendering the unique quality of Mediterranean light marks him as a key figure in the development of the Valencian school's distinctive identity.

Significant Works and Themes

Throughout his long career, Joaquín Agrasot produced a substantial body of work, exploring various themes within his characteristic style. Several paintings stand out as representative of his artistic concerns and achievements:

The Death of the Duke of Montpensier (La Muerte del Duque de Montpensier): This historical genre painting depicts the aftermath of the duel in 1870 where Antoine, Duke of Montpensier, killed Infante Enrique de Borbón. Agrasot likely focused on the dramatic and tragic aspects of the event, showcasing his ability to handle historical subjects with realistic detail and emotional weight, a common practice for academic painters seeking recognition.

Temptation of Saint Augustine (Tentación de San Agustín): This work, tackling a religious theme with historical overtones, demonstrates Agrasot's versatility. The high estimated value mentioned in recent auction catalogues (¥15.22 million - ¥45.68 million) suggests it is considered a major work, likely impressive in scale and execution, perhaps blending historical accuracy with dramatic intensity and the rich detail characteristic of his style.

Two Friends (Dos Amigos): Often cited as a typical example of his Costumbrista work, this painting likely depicts a scene of camaraderie between two Valencian men, perhaps peasants or local types, possibly sharing a drink or conversation. Such works allowed Agrasot to explore character, costume, and local atmosphere with warmth and authenticity.

Valencian Couple (Pareja Valenciana): Similar to Two Friends, this title suggests a focus on regional types and customs, likely portraying a man and woman in traditional Valencian attire within a characteristic setting. These paintings celebrated local identity and provided picturesque glimpses into Spanish life for both domestic and international audiences.

Guitarrista dormido (Sleeping Guitar Player): This subject, the resting musician, was a popular motif in Spanish genre painting. Agrasot's version would likely emphasize the relaxed pose, the details of the instrument and costume, and the play of light and shadow in the setting, creating a quiet, atmospheric scene typical of Costumbrismo.

The Sisters Charity (Las Hermanas de la Caridad): This painting earned Agrasot a Silver Medal at the Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition of 1876. The title suggests a scene involving nuns engaged in charitable work, a theme combining religious sentiment with social observation, likely rendered with the realism and attention to detail that characterized his award-winning works.

Washerwomen at the River (Lavanderas en el río): A recurring theme in 19th-century genre painting, scenes of washerwomen offered artists the opportunity to depict female labor, social interaction, and the effects of light on water and fabric, often in a picturesque outdoor setting. Agrasot likely approached this theme with his typical focus on Valencian light and local color.

These examples illustrate the range of Agrasot's subject matter, from historical drama and religious themes to intimate scenes of everyday life and characteristic regional types. Common threads include his detailed realism, his interest in Spanish customs, and his masterful handling of light and color, all hallmarks of his mature style.

Agrasot and His Contemporaries

Joaquín Agrasot's artistic journey was deeply intertwined with the network of artists he encountered in Valencia, Rome, and Madrid. His relationships with contemporaries shaped his style, facilitated his career, and placed him within the broader context of 19th-century Spanish art.

The most significant relationship, as discussed, was with Mariano Fortuny y Marsal. Fortuny was not just an influence but a close friend, and Agrasot was an integral part of his circle. This connection provided Agrasot with artistic inspiration, technical knowledge, and potentially greater access to the international art market that Fortuny commanded.

In Rome, Agrasot also associated with Attilio Simonetti (1843-1925), an Italian painter known for his historical and costume genre scenes, similar in spirit to Fortuny's work. Simonetti's own success in the international market may have provided further insights for Agrasot. The landscape painter Martín Rico y Ortega was another key member of this circle, sharing travels and artistic interests with both Fortuny and Agrasot. His focus on light-filled landscapes complemented the genre scenes favored by his friends.

Back in Valencia, Agrasot was a respected figure. He maintained connections with other prominent Valencian artists, such as José Benlliure y Gil (1855-1937), another important Costumbrista painter known for his detailed and colorful scenes of Spanish life. While perhaps differing in specific style, Ignacio Pinazo Camarlench (1849-1916) was another major Valencian contemporary, known for his looser brushwork and exploration of light, eventually moving closer to Impressionism. Agrasot's work, alongside theirs, contributed to the reputation of the Valencian school.

Agrasot also played the role of mentor. The Valencian photographer Vicente Martínez Sanz (1850-1920s), considered a pioneer of Spanish Impressionist photography, received training from Agrasot and maintained a lifelong friendship with him. This connection highlights Agrasot's standing within the Valencian artistic community.

Within the wider Spanish art scene, Agrasot's generation included major figures in academic history painting, such as Eduardo Rosales (1836-1873) and José Casado del Alisal (1832-1886). While Agrasot occasionally tackled historical subjects, his primary focus on genre painting aligned him more closely with the Fortuny circle than with the grand history painting tradition promoted by the Madrid Academy. There might have been underlying tensions or rivalries between these different artistic factions, as hinted at by mentions of disputes involving Fortuny's disciples and figures like Casado.

The Fortuny circle also included Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta, who specialized in elegant portraits and genre scenes, sharing the preciosismo style. The international context is also relevant; the work of French academic painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), known for his detailed Orientalist and historical scenes, resonated with the interests of Fortuny and his circle. Similarly, the meticulous technique of Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891) was admired. Agrasot operated within this complex web of local, national, and international artistic relationships.

Exhibitions, Awards, and Recognition

Throughout his career, Joaquín Agrasot actively sought recognition through participation in major exhibitions, both in Spain and internationally. Success in these venues was crucial for establishing an artist's reputation and securing patronage.

He was a regular participant in Spain's prestigious Exposiciones Nacionales de Bellas Artes (National Fine Arts Exhibitions) held in Madrid. These state-sponsored exhibitions were the primary platform for Spanish artists to showcase their work and compete for official medals, which significantly boosted their careers. Agrasot achieved notable success, winning a third-class medal in the 1864 exhibition and a second-class medal in 1867 (some sources mention 1866 or 1868, indicating consistent recognition in this period). These awards confirmed his standing within the national art scene early in his career.

Agrasot also participated in exhibitions in Barcelona, another important Spanish art center, winning awards there in 1864 and 1867, further solidifying his reputation within Spain.

His work gained international exposure as well. A significant achievement was winning a Silver Medal at the Centennial International Exhibition held in Philadelphia in 1876. This major world's fair provided a global stage for arts and industries. Agrasot's award for his painting The Sisters Charity demonstrated that his work, rooted in Spanish themes, possessed qualities appreciated by an international audience and jury, likely his technical skill and the appealing nature of his genre subjects.

His paintings were acquired by important collectors and institutions. Notably, works by Agrasot entered the collection of the Museo del Prado in Madrid and the Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia, the leading art museum in his home region. The presence of his work in the collection of the Spanish Parliament (Congreso de los Diputados) also signifies official recognition. These acquisitions ensured the preservation of his work and cemented his place in the narrative of Spanish art history.

Critical Reception and Artistic Debates

While Joaquín Agrasot achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime, his work, like that of many artists, was also subject to critical evaluation and positioned within the ongoing artistic debates of the era.

His adherence to the Costumbrista genre and the detailed, luminous style associated with Fortuny placed him firmly within a popular and commercially successful vein of 19th-century art. His technical skill was widely acknowledged, and his ability to capture the essence of Valencian life was praised. He was regarded as a leading figure within the Valencian school.

However, some criticisms or qualifications might have arisen. The very preciosismo or meticulous detail inherited from Fortuny, while admired by many, could sometimes be seen by critics favoring broader, more suggestive styles (like those emerging with Impressionism) as overly finished or lacking in spontaneity. The focus on picturesque or anecdotal genre scenes, central to Costumbrismo, might have been viewed by some as less ambitious than the grand historical or mythological subjects favored by the strictest academic tradition, or less innovative than the emerging modern art movements.

Mentions of his works being criticized for their "huge size" or "dramatic" quality require context. It's possible that some of his larger exhibition pieces, designed to make an impact in crowded salons, employed a scale or dramatic intensity that some critics found excessive for genre subjects, perhaps contrasting with the smaller, more intimate tableautin format often associated with Fortuny himself.

The reference to potential friction involving Fortuny's disciples and figures like José Casado del Alisal points to the complex dynamics and rivalries within the Spanish art world. Casado del Alisal represented a more sober, formal strand of history painting associated with the Madrid Academy, potentially contrasting with the more cosmopolitan, technically brilliant, and market-savvy approach of the Fortuny circle based partly in Rome and Paris. Agrasot, as a key member of Fortuny's group, would have been situated within these debates about the direction of Spanish art.

Despite any such debates or criticisms, Agrasot maintained a strong reputation, particularly in Valencia, and his work continued to find appreciative audiences and collectors throughout his career.

Later Years and Legacy

After his formative years and time spent abroad, particularly in Italy, Joaquín Agrasot eventually settled back in Valencia. He remained active as a painter for many decades, continuing to produce works that celebrated the life and landscapes of his native region. He became an established and respected figure in the Valencian artistic community, witnessing the rise of the next generation of artists, including the internationally acclaimed Joaquín Sorolla.

He continued to refine his style, always maintaining his commitment to realism, detailed observation, and the vibrant depiction of light. His long career allowed him to create a significant oeuvre that provides a valuable visual record of Spanish, and particularly Valencian, society during a period of transition.

Joaquín Agrasot y Juan died in Valencia on January 8, 1919, at the age of 83. He was buried in a local church, marking the end of a long and productive life dedicated to art.

His legacy endures primarily through his paintings, which are held in major Spanish museums and private collections. He is remembered as:

A leading exponent of the Costumbrista genre in Valencia, capturing the region's unique customs and types with skill and affection.

A master in the depiction of light, particularly the intense sunlight of the Mediterranean, making him an important precursor to the Valencian Luminist movement.

A key member of the influential circle around Mariano Fortuny y Marsal, successfully adapting the 'Fortunyist' style to Spanish themes.

A technically proficient artist whose works were recognized with awards both nationally and internationally.

An important figure in the history of the Valencian school of painting.

His paintings continue to be appreciated for their vibrant color, detailed execution, and evocative portrayal of a bygone era in Spanish life. They offer a window into the world of 19th-century Valencia, rendered by an artist who was both a skilled technician and a keen observer of his environment.

Conclusion

Joaquín Agrasot y Juan occupies a distinguished place in the annals of 19th-century Spanish art. As a prominent member of the Valencian school and a close associate of the celebrated Mariano Fortuny, he skillfully navigated the artistic currents of his time. His dedication to Costumbrismo allowed him to create a rich and enduring portrait of Spanish life, particularly the customs, people, and luminous landscapes of his native Valencia.

His mastery of light and color, honed through academic training and refined by his experiences in Italy and his association with Fortuny, resulted in works of vibrant realism and meticulous detail. While influenced by the international success of Fortunyism, Agrasot forged his own path, applying these advanced techniques primarily to local themes, thereby contributing significantly to the sense of regional identity in Spanish art.

Through numerous exhibitions and awards, both in Spain and abroad, Agrasot achieved significant recognition during his lifetime. His work continues to be valued for its technical excellence, its historical documentary value, and its sheer visual appeal. He remains a key figure for understanding the evolution of Spanish genre painting and the development of the distinctive Valencian interest in capturing the effects of Mediterranean light, leaving behind a legacy as a talented and dedicated chronicler of his time and place.