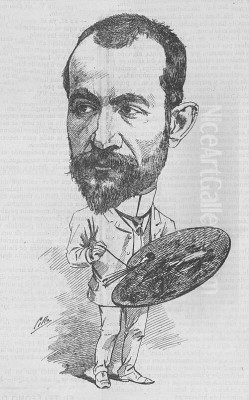

Ángel Lizcano y Esteban, a name that resonates with connoisseurs of 19th and early 20th-century Spanish art, represents a fascinating intersection of tradition and the evolving artistic currents of his time. Born in 1846 and passing away in 1929, Lizcano's career spanned a period of significant social, political, and cultural transformation in Spain. He is particularly noted for his adeptness in capturing the essence of Spanish popular life, often through a stylistic lens deeply influenced by the towering figure of Francisco de Goya. While perhaps not achieving the same stratospheric fame as some of his contemporaries, Lizcano's contributions to genre painting and his engagement with the Goyaesque tradition offer a valuable insight into the artistic landscape of his era.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

The precise details of Ángel Lizcano y Esteban's birthplace and the exact location of his passing remain somewhat elusive in readily available records, a common occurrence for artists who, while respected, did not achieve the level of biographical scrutiny afforded to the era's superstars. However, his active period is well-documented, placing him firmly within the vibrant artistic milieu of late 19th-century Madrid. It is known that Lizcano, who also sometimes used the cognomen "Monedero," was an active participant in the Spanish art scene. A significant indicator of his formal engagement with the art establishment was his submission of a work to the prestigious Nacional de Bellas Artes (National Exhibition of Fine Arts) in Madrid in 1881. These exhibitions were crucial platforms for artists to gain recognition, patronage, and critical appraisal.

Participation in such an event suggests a formal artistic education, likely at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid, which was the principal institution for artistic training in Spain. The Academy, founded in the 18th century, had been the training ground for Goya himself, as well as for subsequent generations of Spanish masters, including Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz, a dominant figure in mid-19th century Spanish art, and later, artists like Joaquín Sorolla and Ignacio Zuloaga, though their styles would diverge significantly. The curriculum would have emphasized drawing from casts and live models, copying Old Masters, and a thorough grounding in perspective and composition, providing a solid technical foundation upon which artists could build their individual styles.

The Enduring Influence of Goya

One of the most frequently cited aspects of Lizcano's art is its connection to Francisco de Goya (1746-1828). Goya's shadow loomed large over 19th-century Spanish art, and Lizcano was one of many artists who drew inspiration from his thematic concerns and stylistic innovations. Lizcano was particularly known for his depictions of "majos" and "majas," the archetypal figures of Madrid's working class, whose distinctive attire and spirited demeanor Goya had immortalized in numerous paintings and tapestry cartoons. These figures, with their colorful sashes, embroidered jackets, and confident poses, became symbols of a certain Spanish national identity.

Lizcano's engagement with Goya's style was not mere slavish imitation but rather an adoption of a visual language that resonated with popular taste and historical consciousness. Some critics have noted that while Lizcano's works echo Goya's themes and compositions, particularly those found in Goya's sketches for the Royal Tapestry Factory, they might not always capture the profound psychological depth or the biting social satire of the Aragonese master. Goya's tapestry cartoons, such as The Parasol or Blind Man's Bluff, while charming, also contained subtle social commentaries. Later, Goya's art would delve into much darker territories with The Disasters of War and the Black Paintings. Lizcano's interpretation seems to have focused more on the picturesque and anecdotal aspects of Goya's legacy, which found a ready market. This Goyaesque current was also explored by other artists like Eugenio Lucas Velázquez (1817-1870) and his son, Eugenio Lucas Villaamil (1858-1918), who were renowned for their pastiches and works "in the style of" Goya, sometimes leading to complex issues of attribution.

Costumbrismo and the Depiction of Spanish Life

Ángel Lizcano y Esteban was a significant practitioner of costumbrismo, a genre of painting that focused on depicting the everyday life, customs, traditions, and types of ordinary people. This movement, which flourished in Spain throughout the 19th century, was akin to genre painting in other European countries but possessed a distinctly Spanish character. It was fueled by a romantic interest in national identity, folklore, and the picturesque, often catering to both a domestic audience and foreign travelers eager for exotic representations of Spain.

Lizcano's costumbrista scenes are characterized by their lively detail, vibrant characters, and narrative clarity. He excelled in capturing the atmosphere of local festivals, market scenes, and popular entertainments. These works served as visual documents of a society undergoing change, preserving moments of traditional life that were gradually being eroded by modernization. Other notable costumbrista painters who contributed to this rich tradition include Valeriano Domínguez Bécquer (1833-1870), whose delicate watercolors and oils captured Andalusian and Castilian scenes with great sensitivity, and Leonardo Alenza y Nieto (1807-1845), known for his satirical and often melancholic portrayals of Madrid life. The international success of Mariano Fortuny (1838-1874), with his dazzling technique and exotic tableautin paintings, also gave a particular impetus and cachet to Spanish genre scenes, though Fortuny's style was more precious and internationally oriented than Lizcano's more direct approach.

Representative Works and Thematic Concerns

Several of Ángel Lizcano y Esteban's paintings stand out as representative of his style and thematic preoccupations. His work Vendedora de naranjas (Orange Seller Woman), dated 1877, an oil on canvas measuring 38 x 30 cm, is a fine example of his intimate genre scenes. It likely portrays a street vendor, a common sight in Spanish cities, capturing a moment of daily commerce with warmth and realism. The focus on a single figure allows for a more personal character study, a hallmark of effective genre painting.

Another significant work is La fiesta de San Isidro (The Festival of San Isidro). San Isidro Labrador is the patron saint of Madrid, and his feast day in May is celebrated with pilgrimages, outdoor picnics, and popular festivities on the Pradera de San Isidro (San Isidro's Meadow). Goya himself famously depicted this festival in works like The Meadow of San Isidro (1788), offering a panoramic view of the bustling crowds. Lizcano's rendition would have continued this tradition, capturing the lively atmosphere, the diverse array of attendees, and the specific customs associated with this important Madrilenian event. Such paintings were popular for their evocation of communal identity and shared cultural experiences.

The painting Baile en el merendero de la Tía Cotilla (Dance at Aunt Cotilla's Picnic Spot), measuring 89 x 130 cm, further illustrates Lizcano's interest in scenes of popular leisure and entertainment. Merenderos, or outdoor picnic spots and taverns, were common gathering places for working-class Madrileños, offering food, drink, music, and dancing. Lizcano's depiction would likely be filled with animated figures, capturing the joy and social interaction of such an occasion. These scenes provided ample opportunity to depict varied human types, colorful costumes, and dynamic compositions.

His Corrida de toros (Bullfight Scene) or Escena de Corrida taps into another quintessential Spanish theme. The bullfight, a spectacle of bravery, skill, and ritual, has been a perennial subject in Spanish art, famously depicted by Goya in his Tauromaquia series and numerous paintings. Lizcano's bullfight scenes would have focused on the drama and color of the event, appealing to the public's fascination with this traditional spectacle. These works often highlighted the bravery of the matador, the ferocity of the bull, and the enthusiastic reactions of the crowd, reflecting a deep-seated cultural phenomenon. The depiction of Basque culture, possibly through specific regional attire or settings in some of his works, also points to his broader interest in the diverse cultural tapestry of Spain, a theme also explored with great vigor by artists like Ignacio Zuloaga (1870-1945), who became particularly known for his powerful portrayals of Basque figures and Castilian landscapes.

Lizcano in the Context of His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Lizcano's position, it's useful to consider him alongside other prominent Spanish artists of his time. The latter half of the 19th century in Spain was a period of artistic richness and diversity. While Lizcano adhered to a more traditional, Goya-influenced realism and costumbrismo, other currents were also gaining traction.

The towering figure of Mariano Fortuny, with his brilliant technique and international acclaim, set a high bar for technical virtuosity and influenced a generation known as "Fortunistas." Artists like José Villegas Cordero (1844-1921) and Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta (1841-1920), Federico's son, achieved considerable success with their polished genre scenes and portraits, often catering to an affluent international clientele.

Historical painting also remained a prestigious genre, with artists like Francisco Pradilla Ortiz (1848-1921), famed for his monumental Joanna the Mad, and Antonio Gisbert (1834-1901), known for The Execution of Torrijos and his Companions, creating large-scale works that narrated key moments in Spanish history. Lizcano's focus on smaller-scale genre scenes offered a different, more intimate perspective on Spanish life.

As the century drew to a close and the 20th century began, new artistic winds began to blow. Joaquín Sorolla (1863-1923) emerged as a master of light, his vibrant beach scenes and portraits capturing the Mediterranean sun with unparalleled brilliance. His style, often termed "Luminism," was a Spanish interpretation of Impressionistic concerns with light and atmosphere, though he always maintained a strong foundation in realist drawing. Ignacio Zuloaga, mentioned earlier, offered a more somber and dramatic vision of Spain, often focusing on its austere landscapes and resilient people, sometimes seen as part of the "Generation of '98" ethos, which grappled with Spain's identity after the loss of its last colonies. Darío de Regoyos (1857-1913) was one of the few Spanish artists to more directly embrace Impressionist and Pointillist techniques, often depicting the landscapes and social realities of "Black Spain."

Within this diverse landscape, Lizcano carved out his niche. He was not an avant-garde innovator in the mold of a Picasso (born 1881, thus a younger contemporary) or Juan Gris, nor did he achieve the sweeping national and international fame of Sorolla. However, his dedication to depicting the everyday life of Spain, filtered through a Goyaesque sensibility, provided a consistent and appreciated body of work. He shared with artists like José Benlliure y Gil (1855-1937), also known for his detailed and anecdotal genre scenes, a commitment to narrative clarity and accessible subject matter.

The Artistic Climate: Academies, Exhibitions, and Patronage

The art world in which Lizcano operated was largely structured around official institutions like the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando and the National Exhibitions of Fine Arts. These exhibitions, held periodically, were major events where artists could win medals, secure commissions, and gain public recognition. The state was a significant patron, acquiring works for national museums and public buildings. Private collectors also played an increasingly important role, particularly for genre paintings that were well-suited for domestic interiors.

Lizcano's participation in the 1881 National Exhibition indicates his engagement with this system. While the provided information doesn't specify if he won any awards, the mere acceptance of his work was a mark of professional standing. The critical reviews and public reception at these exhibitions could significantly shape an artist's career. The taste of the time often favored historical paintings, grand portraits, and well-executed genre scenes. Lizcano's work, with its clear narratives and appealing subject matter, would have found a receptive audience.

The "controversy" or discussion surrounding the Goya-like qualities of some works attributed to or associated with Lizcano is typical of artists who work closely in the style of a great master. It speaks to the enduring power of Goya's artistic personality and the desire of later artists to connect with his legacy. Such stylistic affinities could sometimes lead to misattributions or debates among connoisseurs, but they also highlight the lineage and transmission of artistic ideas.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

Ángel Lizcano y Esteban's legacy lies in his contribution to the rich tapestry of 19th-century Spanish genre painting. He was a skilled observer of his society, adept at translating the vibrancy of Spanish popular culture onto canvas. His works serve as valuable historical documents, offering glimpses into the festivals, occupations, and social customs of his time. The influence of Goya on his art is undeniable and places him within a significant tradition of Spanish painting that continued to explore themes and stylistic approaches pioneered by the Aragonese master.

While he may not be as widely known internationally as Goya, Velázquez, Picasso, or Sorolla, Lizcano holds a respectable place within the canon of Spanish art. His paintings are found in various Spanish collections and appear in art market auctions, indicating a continued appreciation for his work. He represents a type of artist crucial to any national school: the dedicated professional who, while perhaps not revolutionizing art, diligently and skillfully chronicles the life of his time, contributing to the broader cultural heritage. His depictions of majos, bullfights, and festive gatherings helped to solidify a certain visual iconography of Spain that persisted well into the 20th century.

Artists like Lizcano provide depth and context to the art historical narrative. They demonstrate the prevailing tastes, the influence of major figures, and the everyday concerns that found artistic expression. His commitment to realism, combined with the picturesque elements of costumbrismo and the enduring appeal of the Goyaesque, ensured his relevance during his lifetime and his continued interest for art historians and enthusiasts today. He was part of a generation that included figures like the aforementioned Ricardo Arredondo y Calmache (1850-1911), known for his views of Toledo, or José Jiménez Aranda (1837-1903), a master of anecdotal historical genre, all contributing to a multifaceted vision of Spain.

Conclusion

Ángel Lizcano y Esteban (1846-1929) was a Spanish painter whose career successfully navigated the artistic currents of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Deeply influenced by Francisco de Goya, he became a notable exponent of costumbrista painting, capturing the everyday life, traditions, and popular types of Spain with skill and affection. Works such as Vendedora de naranjas, La fiesta de San Isidro, and Corrida de toros exemplify his dedication to these themes, rendered in a realistic style that resonated with the tastes of his time.

While specific details of his early training and later life, including his precise birth and death locations or any formal teaching roles, are not extensively documented in all common sources, his participation in the National Exhibition of Fine Arts in 1881 attests to his professional standing. He operated within an artistic environment that included towering figures like Mariano Fortuny, Joaquín Sorolla, and Ignacio Zuloaga, each contributing to the diverse panorama of Spanish art. Lizcano's particular contribution was his consistent and engaging portrayal of Spanish popular culture, keeping alive the Goyaesque tradition of depicting "majos" and scenes of everyday life. His art offers a window into a bygone era, preserving the color and spirit of Spanish society and earning him a valued place in the history of Spanish painting. His work continues to be appreciated for its narrative charm, its historical value, and its connection to one of Spain's greatest artistic legacies.