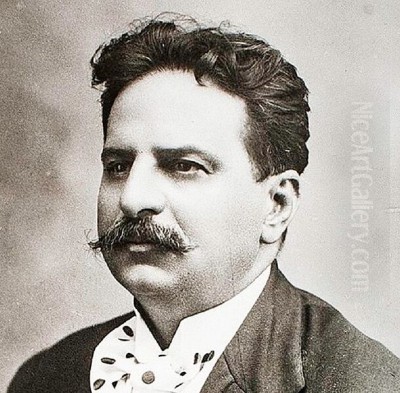

Joaquín Clausell Traconis stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of Mexican art, a painter whose canvases shimmer with the vibrant light and atmosphere of his homeland. Born on June 16, 1866, in the city of San Francisco de Campeche, Campeche, Clausell's life was a fascinating tapestry woven with threads of artistic passion, legal acumen, and fervent political activism. He is celebrated today as one of Mexico's foremost Impressionist painters, a master who translated the fleeting moments of nature into enduring works of art.

His heritage was a blend of cultures, with a Spanish father, José Clausell, from Catalonia, and a Mexican mother, Marcelina Traconis, from Campeche. This dual background perhaps contributed to his unique perspective, one that would eventually find its most profound expression on canvas, capturing the essence of Mexico through a European-influenced artistic lens.

Early Life and Political Awakening

Clausell's early years were marked by a rebellious spirit and a keen intellect. His formal education began in his native Campeche, but his outspoken nature soon set him on a collision course with authority. In 1883, at a young age, he was reportedly expelled from the Instituto Campechano for publicly criticizing the state governor, Joaquín Baranda, during a commemorative event. This early display of defiance foreshadowed his later involvement in national politics.

Seeking new opportunities, Clausell moved to Mexico City around the age of twenty, approximately in 1886. There, he initially pursued studies in engineering for a year before transitioning to law at the prestigious Escuela Nacional de Jurisprudencia. Despite his commitment to legal studies, which he successfully completed, earning a law degree, his innate passion for art began to surface more prominently during this period.

His political activism, however, did not wane. The late 19th century in Mexico was dominated by the lengthy rule of President Porfirio Díaz, a period known as the "Porfiriato." While it brought modernization and economic development, it was also characterized by authoritarianism and suppression of dissent. Clausell, with his strong convictions, found himself increasingly drawn into the opposition.

Journalism, Imprisonment, and Exile

In the early 1890s, Clausell ventured into journalism, a powerful tool for political expression. Alongside friends, he co-founded "El Demócrata," a newspaper explicitly critical of the Díaz regime. His writings were sharp and often inflammatory, challenging the established order. One notable incident involved organizing a student rally to honor Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, a liberal ex-president; this act led to his arrest for allegedly disrupting a funeral and charges of sedition, resulting in several months of imprisonment in the infamous Belén Prison.

His most significant confrontation with the Díaz government came in 1892. Clausell was a leading figure in organizing student movements protesting Díaz's controversial third re-election. His activities, including publishing political manifestos and mobilizing public opinion through "El Demócrata," led to his arrest once more. The newspaper itself became a thorn in the side of the government, with Clausell reportedly penning articles from his prison cell, exposing issues like illegal gambling establishments and abuses of judicial power.

Collaborating with fellow journalist Heriberto Frías, Clausell wrote a series of fictionalized accounts of military actions in Tomóchic, Chihuahua, under the shared pseudonym "Barreta." These articles, published in "El Demócrata," were perceived as highly critical of the federal army's brutal campaign against the Tomochitecos, further enraging the authorities. Facing escalating persecution and the threat of prolonged imprisonment or worse, Clausell made the difficult decision to flee Mexico.

His escape was reportedly dramatic, and he initially sought refuge in the United States, spending time in New York. From there, he made his way to Paris, France, arriving in a city that was then the undisputed epicenter of the art world. This period of exile, though forced upon him, would prove to be transformative for his artistic development.

Parisian Epiphany: The Embrace of Impressionism

Paris in the 1890s was alive with the revolutionary spirit of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Though the initial "scandal" of Impressionism had passed, its influence was pervasive. It was here that Joaquín Clausell, the lawyer and political activist, fully embraced his destiny as a painter. He immersed himself in the artistic milieu, visiting galleries, museums, and likely interacting with artists.

Crucially, he encountered the works of the great French Impressionist masters. He was profoundly influenced by the light-filled canvases of Claude Monet and the sensitive landscapes of Camille Pissarro. He absorbed their techniques: the broken brushwork, the emphasis on capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, the practice of painting en plein air (outdoors), and the use of a vibrant, often unmixed palette. Artists like Edgar Degas, with his dynamic compositions, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, with his joyful depictions of life, also contributed to the rich artistic environment Clausell experienced.

During his time in Paris, Clausell also reportedly befriended the renowned French writer Émile Zola, a champion of Impressionism and a fierce advocate for justice, famously demonstrated in the Dreyfus Affair. Zola's encouragement may have further solidified Clausell's resolve to pursue art. While largely self-taught in terms of formal art instruction, his time in Paris served as an informal, yet deeply impactful, apprenticeship. He learned by observing, absorbing, and experimenting.

Return to Mexico: A Dual Life and Artistic Flourishing

After approximately a year in Paris, the political climate in Mexico shifted enough for Clausell to consider returning. Around 1906 (though some sources suggest an earlier return, the period of significant artistic output begins post-Paris), he was back in Mexico City. He resumed his legal career, which provided him with financial stability, but his true passion now lay in painting.

He established a studio in the Palacio de los Condes de Santiago de Calimaya, a historic colonial-era building in the heart of Mexico City (now the Museum of the City of Mexico). This studio became legendary. It wasn't a conventional, tidy workspace; instead, Clausell famously painted directly onto the walls of his rooms, covering them with landscapes, seascapes, and vibrant studies of light and color. These "wall paintings" became an extension of his canvas work, a continuous, immersive artistic environment.

Clausell's art from this period onward is characterized by its deep engagement with the Mexican landscape. He traveled extensively, seeking out the diverse natural beauty of his country. The rugged coastlines of the Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico, the dense forests, the majestic volcanoes like Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl, and the verdant valleys all found their way into his work.

Clausell's Artistic Style: A Mexican Impressionism

While deeply indebted to French Impressionism, Joaquín Clausell was not a mere imitator. He adapted the Impressionist vernacular to the unique light, colors, and forms of Mexico, creating a distinctly Mexican Impressionism. His style is characterized by several key elements:

Luminous Color and Light: Clausell had an extraordinary sensitivity to light. His paintings capture the intense, clear light of the Mexican highlands and the hazy, humid atmosphere of its coasts. He used color boldly, often employing vibrant, contrasting hues to convey the brilliance of the sun or the deep shadows of a forest. His palette could range from delicate pastels to rich, saturated tones.

Expressive Brushwork: He applied paint with vigorous, often thick, impasto strokes, giving his canvases a tactile quality. This technique, learned from the Impressionists, allowed him to convey the dynamism of nature – the crashing of waves, the rustling of leaves, the movement of clouds. His brushwork was not just descriptive but also emotionally expressive.

Focus on Landscape: The overwhelming majority of Clausell's oeuvre consists of landscapes. He was a keen observer of nature, and his paintings are intimate portrayals of specific places, imbued with a sense of atmosphere and mood. Unlike his great predecessor in Mexican landscape painting, José María Velasco, whose work was more detailed and panoramic in the academic tradition, Clausell's approach was more immediate and subjective, focused on capturing a personal, sensory experience of the landscape.

Spontaneity and Immediacy: Many of his works have a sketch-like quality, suggesting they were painted quickly, en plein air, to capture a fleeting moment. This spontaneity is a hallmark of Impressionism, and Clausell embraced it fully.

While primarily a landscapist, Clausell occasionally incorporated symbolic or even religious elements into his work, though these are less common. His primary focus remained the direct, unfiltered experience of nature. He was also influenced by the Spanish painter Joaquín Sorolla, whose sun-drenched Valencian beach scenes shared a similar interest in capturing brilliant light and vigorous brushwork.

Representative Works

Joaquín Clausell was a prolific painter, and many of his works are now held in major Mexican museums and private collections. Some of his most notable and representative pieces include:

_Atardecer en el mar, la ola roja_ (Sunset at Sea, The Red Wave, c. 1910): This iconic painting exemplifies Clausell's mastery of color and movement. He captures the dramatic moment of a wave cresting under a fiery sunset, the water rendered in bold strokes of red, orange, and deep blue. It’s a powerful, almost abstract, depiction of the sea's energy.

_Fuentes Brotantes, Bosque Azul_ (Gushing Fountains, Blue Forest) or similar titles depicting the Fuentes Brotantes National Park: Clausell painted numerous scenes from this park near Tlalpan, south of Mexico City. These works often feature lush vegetation, dappled sunlight filtering through trees, and the play of light on water. His use of blues and greens creates a cool, immersive atmosphere, sometimes with a Post-Impressionist intensity reminiscent of Van Gogh's expressive use of color and texture.

_Marina_ (Seascape) series: Clausell produced many seascapes, often depicting the rocky coasts and turbulent waters of the Pacific. These works showcase his ability to capture the raw power and changing moods of the ocean, with dynamic compositions and rich textures.

Volcano Landscapes: Like his contemporary Dr. Atl (Gerardo Murillo), Clausell was fascinated by Mexico's volcanoes. He painted Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl, capturing their majestic presence against the vast Mexican sky, often experimenting with different light conditions and atmospheric effects.

His studio walls themselves, covered in murals and studies, could be considered a monumental, evolving artwork, though sadly, much of this ephemeral work is not preserved in the same way as his canvases.

Contemporaries, Collaborators, and Artistic Circle

Joaquín Clausell was part of a vibrant artistic and intellectual scene in Mexico City. He interacted with many of an era's leading figures.

In the realm of art, he was a friend and contemporary of Dr. Atl (Gerardo Murillo), a key figure in the Mexican modernist movement, a painter, writer, volcanologist, and cultural promoter. While Dr. Atl's style evolved towards a more monumental and symbolic representation of the landscape (using his "Atl-colors," a type of pastel stick he invented), both artists shared a profound love for the Mexican terrain.

Clausell also knew Diego Rivera, one of the "Tres Grandes" of Mexican Muralism. Though Rivera's path would lead him to large-scale public murals with strong social and political messages, his early European period also saw him experiment with Impressionism and Cubism. Clausell's generation helped pave the way for the artistic renaissance that Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros would later spearhead.

Saturnino Herrán, another important contemporary, focused on figurative work that celebrated Mexican identity, often with a Symbolist inflection. While their subject matter differed, both Herrán and Clausell contributed to the growing sense of Mexicanidad (Mexicanness) in the arts.

Other artists of the period with whom Clausell likely had contact or whose work formed part of the artistic dialogue include Alfredo Ramos Martínez, another pioneer of Mexican modernism who also spent time in Europe and championed open-air painting schools, and Francisco Goitia, known for his more somber, expressionistic depictions of indigenous life and suffering.

In his political and journalistic activities, Clausell collaborated with figures like Heriberto Frías on "El Demócrata." He also supported, at different times, political figures such as Francisco I. Madero, who led the 1910 revolution against Díaz, and later, more controversially, Victoriano Huerta. His political allegiances could be complex and sometimes shifted with the turbulent tides of the Mexican Revolution. Other journalistic collaborators included Moheno, Gabriel González Mier, and Alberto Santibañez.

Later Years and Untimely Death

Joaquín Clausell continued to paint and practice law throughout his life. He remained a somewhat enigmatic figure, dedicated to his art but not actively seeking the limelight of exhibitions or self-promotion in the way some of his contemporaries did. His studio was his sanctuary, his primary place of creation and communion with his artistic vision.

His life came to an unexpected and tragic end. On November 28, 1935, Joaquín Clausell died at his home in the Lagunas de Zempoala region, a beautiful natural area that he loved and often painted. The cause of death was reportedly injuries sustained from a fall, possibly from a cliff or embankment while he was out in the landscape, perhaps scouting a new scene to paint. He was 69 years old.

Legacy and Influence on Mexican Art

Joaquín Clausell's contribution to Mexican art is significant and multifaceted. He is widely regarded as the most important Impressionist painter of Mexico and a key figure in the transition from 19th-century academic art to 20th-century modernism.

His primary legacy lies in his introduction and adaptation of Impressionist techniques to the Mexican context. He demonstrated that this European movement could be a powerful tool for interpreting and celebrating the unique character of the Mexican landscape. His work showed a path away from the more literal, detailed style of Velasco towards a more personal, expressive, and light-focused approach.

While he may not have had formal students in an academic sense, his work undoubtedly influenced subsequent generations of Mexican landscape painters. His emphasis on color, light, and direct observation of nature provided an alternative to the more narrative or politically charged art of the muralists, though both streams contributed to the richness of Mexican art.

Art historians and critics today recognize Clausell's importance. His paintings are prized for their beauty, their technical skill, and their unique fusion of international artistic currents with a deep-seated Mexican sensibility. He is often paired with José María Velasco as one of the two giants of Mexican landscape painting, each representing a different era and approach but united by their profound connection to the land.

His work continues to be exhibited and studied, offering a window into the soul of a painter who saw the world in vibrant hues and fleeting moments, and who dedicated his life to capturing that vision on canvas and on the walls of his extraordinary studio. He remains an enduring testament to the power of art to transcend politics and time, leaving behind a luminous legacy that continues to inspire.

Conclusion

Joaquín Clausell was more than just a painter; he was a man of deep convictions, a restless spirit who navigated the turbulent waters of Mexican politics and the revolutionary currents of modern art. From the rebellious student in Campeche to the exiled journalist in Paris, and finally to the master Impressionist in his Mexico City studio, his life was a journey of passion and discovery. His canvases, alive with the light and color of Mexico, stand as a vibrant testament to his artistic genius. He successfully forged a unique Mexican Impressionism, capturing the soul of his nation's landscapes with a sensitivity and vigor that ensures his place among the most important artists Mexico has produced. His legacy is not just in the paintings themselves, but in the enduring inspiration they provide, reminding us of the profound beauty to be found in the natural world and the power of an individual artistic vision.