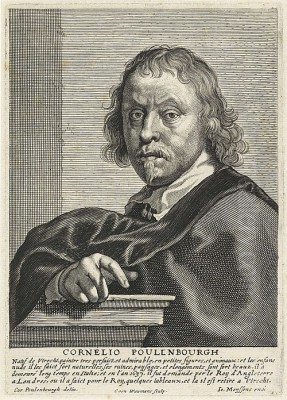

Introduction: Bridging North and South

Cornelis van Poelenburch (c. 1594/1595 – 1667) stands as a pivotal figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age painting. Born in Utrecht, he became one of the leading pioneers of the Italianate style of landscape painting in the Netherlands. His career represents a fascinating confluence of Northern European artistic traditions and the profound impact of the Italian Renaissance and the Roman Campagna. Renowned for his small-scale, exquisitely detailed paintings, often executed on copper or panel, Poelenburch transported viewers to sun-drenched, idealized landscapes populated by mythological figures, biblical characters, and Arcadian nymphs. His work, highly sought after during his lifetime and influential for generations to come, captures a unique blend of meticulous Dutch observation and the warm, luminous atmosphere of Italy. He was not merely a painter but a bridge between two distinct artistic worlds, forging a path that many other Dutch artists would follow.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Utrecht

Cornelis van Poelenburch's artistic journey began in Utrecht, a city with a vibrant and distinct artistic identity within the Dutch Republic. Born around 1594 or 1595, his early artistic education was shaped by the local environment. Crucially, he became a pupil of Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), a highly respected and versatile painter and draughtsman. Bloemaert was a central figure in Utrecht art, known for his Mannerist roots but adaptable style, which later incorporated elements of Caravaggism and classicism. Studying under Bloemaert provided Poelenburch with a solid foundation in drawing, composition, and the technical aspects of painting. Utrecht itself was an artistic hub open to international influences, partly due to its Catholic history and connections. This environment likely fostered Poelenburch's own inclination towards exploring artistic trends beyond the Dutch borders, particularly those emanating from Italy, the cradle of the Renaissance and classical antiquity. Bloemaert's workshop was a training ground for many significant artists, and Poelenburch's time there equipped him with the skills necessary for his future innovations.

The Transformative Italian Sojourn

Around 1617, like many ambitious Northern European artists of his time, Cornelis van Poelenburch embarked on a journey to Italy, a trip that would fundamentally shape his artistic vision and career trajectory. He spent a significant period, primarily between 1617 and 1625/1626, living and working in Rome, with documented visits to Florence as well. Italy, particularly Rome, was considered the ultimate finishing school for artists, offering direct exposure to the masterpieces of classical antiquity and the High Renaissance, including the works of giants like Raphael (1483–1520), whose compositions and idealized figures left an impression on him. The experience of the Italian landscape itself – the rolling hills of the Campagna, the ancient ruins scattered across the countryside, and the unique quality of the Mediterranean light – proved immensely influential. This direct encounter with the classical world and the Italian environment provided a wealth of inspiration that would become central to his art.

In Rome, Poelenburch immersed himself in the city's bustling artistic community. He studied the works of contemporary artists and absorbed the prevailing artistic currents. Perhaps the most significant influence during this period came from the German painter Adam Elsheimer (1578–1610), who had worked in Rome until his death. Although Elsheimer had passed away before Poelenburch's arrival, his legacy loomed large. Elsheimer was renowned for his small, highly detailed paintings on copper, often depicting biblical or mythological scenes within evocative landscapes, characterized by innovative treatments of light and atmosphere. Poelenburch clearly admired Elsheimer's meticulous technique, his handling of light (both natural and artificial), and his ability to create poetic moods within small formats. This influence is evident in Poelenburch's preference for small panels or copper plates and his own detailed, jewel-like landscapes.

Another important figure in Rome was the Flemish landscape painter Paul Bril (1554–1626), who had established a successful career in the city. Bril's idealized landscapes, often featuring classical ruins and a sense of grandeur, also provided a model for Poelenburch and other Northern artists working in Italy. Poelenburch synthesized these influences – the classical ideal, the specific light and landscape of Italy, the technical finesse of Elsheimer, and the established tradition of idealized landscape represented by Bril – to forge his own distinctive style. His time in Italy was not just about learning; it was about transformation, leading him to become a key figure in the development of Dutch Italianate landscape painting. He also found patrons in Italy, including connections with Cosimo II de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, indicating his growing reputation even during his formative years abroad.

The Bentvueghels: Brotherhood in Rome

During his extended stay in Rome, Cornelis van Poelenburch became actively involved in the social and professional lives of the expatriate artist community. He was a founding member of the Bentvueghels (Dutch for "Birds of a Feather"), a society primarily composed of Dutch and Flemish artists working in Rome. Officially known as the "Schildersbent," this confraternity provided mutual support, camaraderie, and a network for artists far from home. The Bentvueghels were known for their bohemian lifestyle and initiation rituals, often involving feasting, drinking, and mock ceremonies held at locations like the supposed Tomb of Bacchus (a Roman sarcophagus). Each member received a nickname, or "bent name." Poelenburch's nickname was "Satyr," a moniker that likely alluded to the frequent appearance of satyrs and other mythological creatures in his Arcadian landscapes, perhaps also hinting at a playful or earthy aspect of his personality or art.

Membership in the Bentvueghels was significant. It placed Poelenburch at the heart of the Netherlandish artistic community in Rome, fostering exchanges of ideas and techniques. Among his contemporaries in this circle was Bartholomeus Breenbergh (1598–1657), another highly important early Dutch Italianate painter whose career parallels Poelenburch's in many ways. Both artists specialized in small-scale Italianate landscapes with ruins and figures, though Breenbergh's style often featured sharper contrasts of light and shadow and a more dramatic flair compared to Poelenburch's typically softer, more harmonious approach. Other members included painters like Pieter van Laer (1599–c. 1642), nicknamed "Il Bamboccio," who would later pioneer a different genre focused on Roman street life. The Bentvueghels, despite their sometimes rowdy reputation, played a crucial role in the lives of these artists, offering a sense of belonging and professional identity in a foreign city, and facilitating the cross-pollination of artistic ideas that defined the Italianate movement. Poelenburch's involvement underscores his integration into this vibrant international artistic scene.

Forging a Signature Style: The Italianate Vision

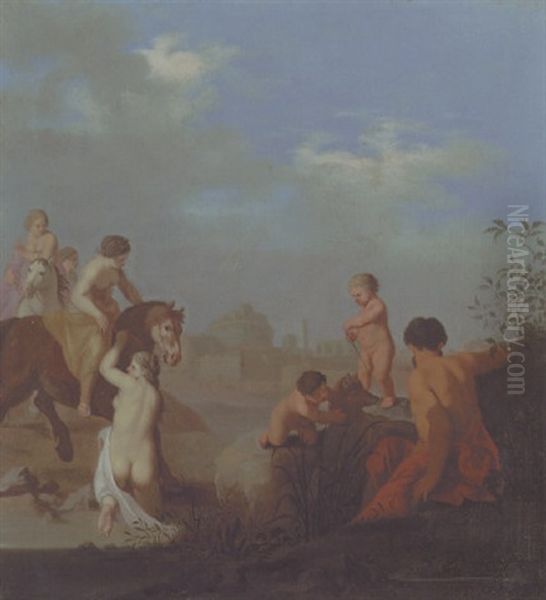

Poelenburch's experiences in Italy culminated in the development of a highly distinctive and influential artistic style. He became a master of the small-format cabinet picture, often painting on copper or smooth wooden panels. This choice of support allowed for an exceptionally refined, enamel-like finish, enhancing the jewel-like quality of his work. His landscapes are typically idealized visions of the Roman Campagna or imaginary Arcadian settings. They feature rolling hills bathed in a warm, golden, or silvery light, clear blue skies often dotted with delicate clouds, and meticulously rendered foliage and rock formations. Classical ruins – crumbling temples, ancient arches, sarcophagi – are frequently incorporated, evoking a sense of nostalgia for antiquity and adding a layer of historical resonance. These elements are rendered with a delicate precision that reflects his Dutch training, but the overall atmosphere is distinctly Italian.

A defining characteristic of Poelenburch's art is his treatment of light. He moved away from the more dramatic chiaroscuro seen in the works of the Utrecht Caravaggisti (like Gerard van Honthorst or Hendrick ter Brugghen) and instead adopted a softer, more diffused illumination, reminiscent of the gentle light of the Italian countryside, particularly influenced by the atmospheric effects captured by Elsheimer. This creates a serene, often idyllic mood in his paintings. His figures, though small in scale relative to the landscape (staffage), are central to the narrative and mood. He specialized in depicting nude or semi-nude figures – nymphs, goddesses, satyrs from mythology, or biblical characters like Adam and Eve or Bathsheba. These figures are often rendered with smooth, porcelain-like skin and graceful poses, drawing inspiration from classical sculpture and Renaissance masters like Raphael. Despite their classical or biblical themes, the figures sometimes wear contemporary details or possess a certain approachability, blending the mythical with a subtle touch of realism. This combination of idealized landscape, classical motifs, specific light quality, and delicate figures became the hallmark of Poelenburch's style and set the standard for the first generation of Dutch Italianate painters.

Return to Utrecht and Established Success

Around 1626 or 1627, Cornelis van Poelenburch returned to his native Utrecht, his reputation preceding him. His Italianate landscapes, with their refined technique and appealing subject matter, found immediate favor with Dutch collectors. The novelty of his style – the sunny, idealized depictions of Italy – offered a contrast to the more topographical or tonal landscapes being produced by some of his Dutch contemporaries. He quickly became one of Utrecht's most successful and sought-after painters. His success is evidenced by his prestigious commissions and his role within the local artistic community. In 1649, he was recorded as one of the heads (along with Abraham Bloemaert and others) of the Utrecht Guild of Saint Luke, the professional organization for painters and other craftsmen, a position reflecting his high standing among his peers. He held leadership roles in the guild again in later years (1657, 1658, 1664), indicating sustained respect within the profession.

Back in Utrecht, Poelenburch continued to produce the type of cabinet-sized Italianate landscapes that had established his fame. While he occasionally incorporated more recognizably Dutch elements into his backgrounds, the core of his work remained rooted in the idealized Italian vision he had developed abroad. His paintings were acquired by prominent collectors within the Dutch Republic, including, reportedly, the Stadtholder Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange. The demand for his work was such that he maintained a successful workshop, training pupils who would help propagate his style. His success demonstrates that there was a significant market in the Netherlands for these idealized, southern-infused scenes, offering collectors a form of escapism and a connection to the classical world. He remained a dominant figure in Utrecht's art scene until his death in 1667.

The London Interlude: Royal Patronage

Poelenburch's fame was not confined to the Netherlands. His reputation reached the English court, and he spent a period working in London, likely between 1637 and 1641. He was invited by King Charles I, a renowned connoisseur and patron of the arts. Charles I's court was a magnet for artistic talent, famously employing the Flemish masters Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), who dominated portraiture and large-scale commissions. Poelenburch's invitation highlights the international appeal of his specialized genre. While not undertaking the grand projects assigned to Rubens or Van Dyck, Poelenburch contributed his characteristic small-scale works to the royal collection. Sources suggest he painted cabinet pictures, possibly including works intended to decorate small pieces of furniture like cabinets, fitting his intimate style.

His time in London placed him in proximity to some of the greatest artists of the era and exposed his work to the sophisticated tastes of the English aristocracy. While details of specific collaborations are scarce, his presence at court alongside figures like Van Dyck underscores his status. He reportedly worked alongside Alexander Keirincx (1600–1652), another landscape painter active at the English court around the same time, sometimes adding figures to Keirincx's landscapes. This English interlude, though relatively brief compared to his time in Italy or his long career in Utrecht, further cemented Poelenburch's international reputation and demonstrated the high regard in which his refined Italianate scenes were held by elite patrons outside the Dutch Republic. He eventually returned to Utrecht, where he remained for the rest of his life.

Collaborations, Workshop, and Influence

Like many successful artists of the Dutch Golden Age, Cornelis van Poelenburch engaged in collaborations and maintained an active workshop. Collaborations were common practice, allowing artists to leverage each other's specializations. Poelenburch, known for his skill in rendering delicate figures, sometimes painted the staffage (human or mythological figures) into landscapes created by other artists. Conversely, other artists might paint the landscape settings for his figures, although Poelenburch was primarily known as a landscape painter himself. Notable collaborators included Jan Both (c. 1610/18–1652), a leading figure of the second generation of Dutch Italianates. The synergy between Poelenburch and Both was significant, with their styles sometimes blending, although Both's landscapes are generally larger and possess a more heroic, atmospheric quality, often influenced by Claude Lorrain. Poelenburch is also known to have collaborated with Alexander Keirincx, as mentioned during his London period, and potentially with Herman Saftleven (1609–1685), another Utrecht-based landscape painter.

Poelenburch's success necessitated a workshop to meet the demand for his paintings. He trained several pupils who absorbed his style and techniques, helping to disseminate the Italianate manner. Among his known pupils are Dirck van der Lisse (1607–1669), Daniel Vertangen (c. 1600–1681/84), and Jan Gerritsz van Bronckhorst (c. 1603–1661), who initially trained with Poelenburch before developing his own career, partly influenced by Caravaggism. These pupils often created works very much in the master's style, sometimes leading to attribution challenges for art historians. Poelenburch's influence extended beyond his direct pupils. His pioneering role in establishing the Italianate landscape genre in the Netherlands paved the way for subsequent generations of artists who traveled to Italy or adopted the style, including prominent figures like Nicolaes Berchem (1620–1683) and Karel Dujardin (c. 1622–1678). His polished technique and idealized vision remained popular well into the 18th century, demonstrating the lasting impact of his artistic formula.

Key Themes and Representative Works

Cornelis van Poelenburch's oeuvre is characterized by a consistent focus on specific themes, primarily drawn from classical mythology and the Bible, set within his signature Italianate landscapes. Arcadian scenes featuring nymphs, satyrs, and shepherds relaxing or bathing in idyllic natural settings were particularly popular. These works evoke a timeless golden age, far removed from the everyday realities of 17th-century Dutch life. Mythological subjects included stories like The Feast of the Gods, often depicted as a gathering of deities in a lush landscape, perhaps inspired by Raphael's frescoes, or narratives such as The Flight of Cloelia, an ancient Roman tale of heroism. Biblical themes were also common, often chosen for their potential to include nude or semi-nude figures within a landscape, such as Adam and Eve (including The Expulsion from Paradise), Lot and his Daughters, or Bathsheba Bathing.

Several works stand out as representative of his style and achievements:

Landscape with Nymphs Bathing (numerous versions): This recurring theme allowed Poelenburch to showcase his skill in depicting the female nude within serene, watery landscapes. Examples can be found in major museums worldwide. Bathsheba Bathing (c. 1640-1650, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) is a prime example, demonstrating his delicate handling of figures, light, and the lush, detailed natural surroundings.

The Feast of the Gods: Poelenburch painted this subject multiple times. These compositions typically feature numerous mythological figures feasting and reclining in an open, idealized landscape, showcasing his ability to handle complex multi-figure arrangements within his characteristic style.

Landscape with Roman Ruins (various titles): Many of Poelenburch's works prominently feature identifiable or imaginary classical ruins, such as the Colosseum or fragments of temples and arches. These paintings, like Roman Campagna Landscape with Ruins (examples in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, and elsewhere), highlight his fascination with antiquity and his ability to integrate architectural elements seamlessly into natural settings.

The Flight of Cloelia: This subject, depicting the Roman heroine Cloelia escaping captivity by swimming across the Tiber with fellow hostages, allowed for a dynamic composition combining figures, water, and landscape, often with Rome depicted in the background.

The Expulsion from Paradise (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam): This work tackles a key biblical narrative, placing Adam and Eve within a verdant, Edenic landscape, demonstrating his ability to convey dramatic moments within his typically serene style.

Cimon and Iphigenia: Based on a story from Boccaccio's Decameron, this theme involves the rough Cimon stumbling upon the sleeping nymph Iphigenia and being transformed by her beauty. It provided another opportunity to depict idealized figures in a pastoral setting.

These works, typically small in scale and executed with meticulous care, are found today in major international collections, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Mauritshuis in The Hague, the Louvre in Paris, the National Gallery in London, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Yale University Art Gallery, attesting to his enduring appeal and historical importance.

Art Historical Significance and Legacy

Cornelis van Poelenburch holds a secure and significant place in the history of Dutch art. He is widely recognized as one of the founders and foremost exponents of the first generation of Dutch Italianate landscape painters. His journey to Italy and subsequent return to Utrecht with a fully formed, Italian-inspired style marked a crucial development in Dutch Golden Age painting. He successfully synthesized the Northern tradition of detailed realism with the idealized beauty, classical themes, and luminous atmosphere of Italy, creating a formula that proved immensely popular and influential. His work offered a distinct alternative to the more naturalistic or tonal landscape traditions developing concurrently in the Netherlands, represented by artists like Jan van Goyen, Salomon van Ruysdael, and later Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema. Poelenburch's art catered to a taste for the exotic, the classical, and the idyllic.

His influence was profound and lasting. He directly trained pupils who continued his style, and his success inspired many other Dutch artists to travel to Italy or adopt Italianate motifs. The subsequent generation of Italianate painters, including Jan Both, Nicolaes Berchem, Karel Dujardin, and Adam Pynacker, built upon the foundations laid by Poelenburch and Breenbergh, often working on larger canvases and developing more complex atmospheric effects, but the core elements of idealized landscapes, warm light, and classical or pastoral staffage remained indebted to the pioneers. Poelenburch's polished technique and appealing subject matter ensured his popularity among collectors throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Even as artistic tastes shifted, his works continued to be valued for their refinement and charm. He stands alongside the Utrecht Caravaggisti (Honthorst, Ter Brugghen, Baburen) and Mannerists like Bloemaert as one of the key figures who shaped the unique artistic identity of Utrecht within the broader context of the Dutch Golden Age, demonstrating the city's openness to international, particularly Italian, influences.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Arcadia

Cornelis van Poelenburch's artistic legacy is defined by his successful fusion of Dutch precision and Italian light. As a foundational figure of the Italianate movement in the Netherlands, he translated his experiences of Italy's landscapes, classical ruins, and artistic heritage into a unique and highly sought-after style. His small, jewel-like paintings on copper and panel offered 17th-century viewers, and continue to offer audiences today, an escape into sunlit, Arcadian realms populated by figures from myth and scripture. While distinct from the more commonly recognized 'realistic' Dutch landscapes, Poelenburch's idealized visions represent an equally important facet of the Dutch Golden Age, reflecting the era's fascination with classical antiquity and the enduring allure of Italy. Through his meticulous technique, his mastery of soft light, and his charmingly rendered figures, Poelenburch created a body of work that secured his place as a significant master, whose influence resonated through Dutch art and whose paintings continue to be admired for their elegance and serene beauty. He remains a testament to the fruitful dialogue between Northern European artistic traditions and the timeless inspiration of the Mediterranean world.