John E. Ferneley Sr. stands as one of the preeminent figures in British sporting art, renowned for his vibrant and meticulously detailed depictions of equestrian life, particularly the dynamic world of fox hunting. Born on May 18, 1782, in the village of Thrussington, Leicestershire, England, and passing away on June 3, 1860, Ferneley's life spanned a period of significant social and artistic change. His career, deeply rooted in the English countryside, captured the essence of aristocratic and gentry pastimes, leaving behind a legacy of paintings that are both historical documents and artistic triumphs.

Humble Beginnings and Auspicious Patronage

Ferneley's origins were modest. He was the son of a village wheelwright, and his early life seemed destined for a trade rather than the fine arts. However, his innate talent for drawing, often practiced on the sides of his father's wagons, did not go unnoticed. Legend holds that the young Ferneley would travel to nearby towns like Leicester and Nottingham to view and sketch paintings, nurturing his artistic inclinations.

A pivotal moment came when his burgeoning skills caught the eye of John Manners, the 5th Duke of Rutland, a prominent local landowner and enthusiast of field sports residing at Belvoir Castle. Recognizing Ferneley's potential, the Duke encouraged him to pursue art professionally. More significantly, he facilitated an apprenticeship for Ferneley under Benjamin Marshall (1768–1835), who was already established as a leading sporting artist of the day.

Apprenticeship under Benjamin Marshall

Around 1801, Ferneley began his formal training with Benjamin Marshall. Marshall, known for his robust, less idealized portrayal of horses compared to some predecessors, provided Ferneley with a strong foundation in equine anatomy and the techniques required to capture the power and spirit of the horse. Marshall's influence is visible in Ferneley's early work, particularly in the solid modelling of the animals and the attention paid to their individual characteristics.

During his time with Marshall, Ferneley also benefited from the opportunity to study at the Royal Academy Schools in London, further honing his skills in drawing and painting. This formal academic exposure, combined with Marshall's practical expertise in sporting subjects, equipped Ferneley with a versatile skill set. He began exhibiting his own works at the Royal Academy in 1806, marking the start of a long and successful exhibiting career that would continue until 1853.

Establishing a Career in Melton Mowbray

After completing his training, Ferneley worked briefly in Dover and Ireland, undertaking commissions. However, his career truly took flight upon his decision to settle in the Leicestershire town of Melton Mowbray in 1814. This move was strategically brilliant. Melton Mowbray was rapidly becoming the undisputed capital of fox hunting in England, attracting wealthy landowners, aristocrats, and sporting enthusiasts from across the country, particularly during the winter hunting season.

The town and its surrounding hunts – the Quorn, the Belvoir, and the Cottesmore – provided Ferneley with an unparalleled source of patronage and subject matter. He immersed himself in this world, becoming the favoured artist for depicting the horses, hounds, and riders that defined the Melton scene. His studio became a hub for the sporting elite, and it was said that "the Melton years were the Ferneley years," highlighting his central role in documenting the golden age of English fox hunting.

The Ferneley Style: Detail, Colour, and Atmosphere

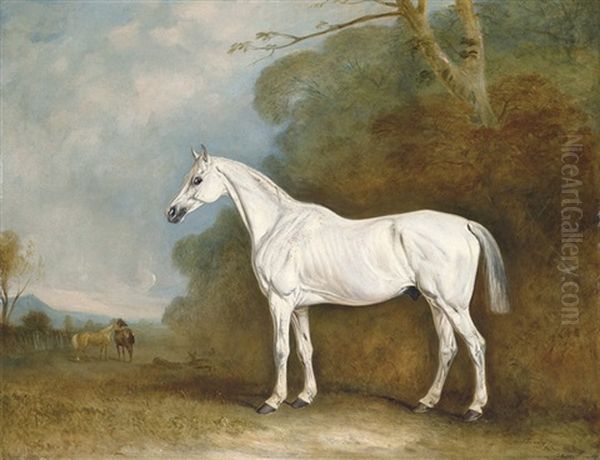

Ferneley developed a distinctive artistic style characterized by meticulous attention to detail, vibrant yet realistic colour palettes, and an exceptional ability to capture the likeness of both horses and their owners. Unlike the often more dramatic or romanticized approaches of some contemporaries, Ferneley's work possessed a clarity and accuracy that appealed greatly to his patrons, who valued faithful representations of their prized animals and memorable hunting days.

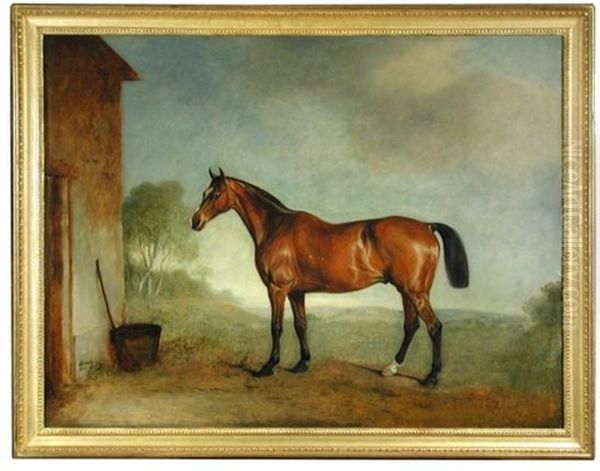

His compositions ranged from individual equine portraits, often set against stable or landscape backgrounds, to complex, panoramic scenes depicting the thrill of the chase. In his portraits, such as Orion, a Chestnut Hunter outside Stables (1831), he rendered the horse's conformation, coat texture, and even its personality with remarkable precision. The tack, the grooming, and the surrounding architecture were all depicted with careful observation.

In his larger hunting scenes, like the various versions of The Quorn Hunt, Ferneley demonstrated a masterful ability to organize numerous figures – riders, horses, and hounds – within expansive landscapes, conveying the energy and social dynamics of the event. He often included recognizable landmarks and accurately portrayed the specific colours and attire associated with different hunts. His landscapes, while often serving as backdrops, were rendered with sensitivity to light and atmosphere, grounding the sporting action within the tangible reality of the English countryside.

Representative Masterpieces

Throughout his prolific career, Ferneley produced numerous works that are now considered highlights of British sporting art.

The Quorn Hunt (various versions, e.g., 1822): These large-scale compositions are perhaps his most famous works, capturing the excitement and social gathering of a meet or run with the Quorn Hunt, one of England's most prestigious hunts. They often feature portraits of prominent members, making them valuable historical records as well as artistic achievements.

Mr Green's Bay Mare: Often cited as a prime example of his skill in equine portraiture, this work showcases his ability to capture the elegance, strength, and individual character of a specific horse, rendered with his typical attention to anatomical accuracy and fine detail.

Seahorse (1826): This painting, depicting a racehorse, demonstrates his versatility beyond hunting scenes. It highlights his understanding of thoroughbred conformation and his ability to convey a sense of poised energy.

The Egyptian Pony (1856): Painted later in his career, this charming work shows his continued dedication to capturing the unique qualities of different breeds. The depiction of the pony and its elaborate tack showcases his skill with colour and texture.

Orion, a Chestnut Hunter outside Stables (1831): A classic example of his individual horse portraits, combining anatomical precision with a sense of the animal's presence and the specificity of its environment.

These works, among many others, cemented Ferneley's reputation and remain highly sought after by collectors and institutions today.

Collaboration with Sir Francis Grant

An interesting aspect of Ferneley's career was his collaboration with Sir Francis Grant (1803–1878). Grant, initially an amateur artist and keen huntsman who frequented Melton Mowbray, became a highly successful portrait painter, eventually rising to become President of the Royal Academy in 1866. During Grant's earlier years, he and Ferneley occasionally collaborated on large hunting pictures.

In these joint works, Ferneley typically painted the horses and hounds, leveraging his specialized expertise, while Grant, with his growing skill in portraiture, would paint the human figures. This partnership allowed them to produce complex compositions efficiently, combining their respective strengths. While they were friends and collaborators, they also operated within the same competitive field of sporting and portrait painting, though Grant's career ultimately took a different trajectory towards mainstream portraiture and academic leadership.

Ferneley in the Context of Sporting Art

John Ferneley Sr. worked during a flourishing period for British sporting art. He is often compared to his great predecessor, George Stubbs (1724–1806). While Stubbs is revered for his profound anatomical studies and almost scientific approach to equine depiction, Ferneley's work is often seen as more directly engaged with the social aspects and dynamic action of contemporary sporting life, particularly hunting. His colours are generally brighter and his compositions often busier than Stubbs's more classically restrained paintings.

Ferneley's direct teacher, Benjamin Marshall, provided a crucial link, moving sporting art towards a more robust and less formal style than seen in some earlier works. Ferneley built upon this, refining the detail and expanding the scope of his compositions.

He was a contemporary of several other notable sporting artists. The Alken family, particularly Henry Thomas Alken Snr (1785–1851) and his son Samuel Henry Alken Jnr (1810-1894), were prolific producers of hunting, coaching, and racing scenes, often characterized by vigorous action and sometimes humorous observation. James Pollard (1792–1867) excelled in depicting coaching and racing scenes with lively detail. John Frederick Herring Snr (1795–1865) was another major figure, particularly famous for his portraits of racehorses, including many Derby and St Leger winners, and his charming farmyard scenes. Herring's meticulous finish often rivalled Ferneley's.

Other significant names in the broader field during or overlapping Ferneley's time include James Ward (1769–1859), known for his powerful, Romantic-influenced animal paintings; Abraham Cooper (1787–1868), who painted battle scenes as well as sporting subjects; Sawrey Gilpin (1733–1807), from an earlier generation but whose influence persisted; Charles Towne (1763-1840), known for his detailed landscapes with animals; and Dean Wolstenholme Snr (1757-1837) and Jnr (1798-1882), both known for their hunting scenes. Later in Ferneley's career, Sir Edwin Landseer (1802–1873) achieved immense fame, though his work often carried more overt narrative and sentimental weight, particularly his depictions of deer and dogs. Richard Ansdell (1815-1885) also gained prominence for his animal and sporting subjects, often collaborating with figure painters like John Phillip.

Within this rich artistic landscape, Ferneley carved out a distinct niche. His deep connection to Melton Mowbray and the hunting community, combined with his consistent quality and reliability, made him the definitive painter of that specific world for nearly half a century. His work offers less of the overt drama of Ward or the anecdotal humour of Alken, focusing instead on accurate representation combined with a feel for the atmosphere of the English countryside and the social rituals of the sporting gentry.

Later Life, Family, and Legacy

Ferneley enjoyed a long and prosperous career based largely in Melton Mowbray. He married his first wife, Sally Kettle, in 1809. Together they had seven children, six of whom survived infancy. Tragically, Sally died in 1836. Ferneley later married Ann Allan in 1848.

His artistic talent was passed down to the next generation. Two of his sons, John Ferneley Jr. (1815–1862) and Claude Loraine Ferneley (1822–1891), also became painters, specializing in sporting subjects in a style heavily influenced by their father. John Jr. often worked in York, while Claude Loraine assisted his father and continued working in Melton Mowbray after his father's death. His daughter Sarah Ferneley (1812-1903) also painted, though she is less well-known than her brothers.

John Ferneley Sr. continued painting almost until his death in Melton Mowbray on June 3, 1860, at the age of 78. He was buried in his home village of Thrussington. He left behind a vast body of work, meticulously documented in his account books, which provide valuable insights into his commissions, patrons, and prices.

His legacy is significant. Alongside Stubbs and Marshall, he is considered one of the triumvirate of great British sporting painters. His work provides an invaluable visual record of a specific era and social milieu – the world of the English country squire and the rituals of the hunt in the late Georgian and early Victorian periods. His paintings are admired for their technical skill, their accuracy, their vibrant depiction of horses and hounds, and their ability to evoke the atmosphere of the English sporting landscape. His works remain highly prized by collectors and are represented in major public and private collections worldwide, including the Tate Britain, the Yale Center for British Art, and numerous regional UK museums. Ferneley successfully elevated sporting art through his dedication, skill, and deep understanding of his subject matter, ensuring his place as a master chronicler of the chase.