John Frost (1890-1937) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes underappreciated, figure in the annals of American Impressionism, particularly celebrated for his evocative portrayals of the Californian landscape. Born into an artistic lineage and educated in the vibrant art scenes of both America and Europe, Frost developed a distinctive style characterized by luminous color, atmospheric depth, and a profound sensitivity to the transient effects of light. Despite a life tragically cut short by illness, his body of work offers a compelling window into the early 20th-century American artistic dialogue with Impressionism, masterfully adapted to the unique environment of the American West.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

John Frost was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1890, into a family where art was not merely a pastime but a way of life. His father was Arthur Burdett Frost Sr. (A.B. Frost), one of America's most distinguished and popular illustrators and cartoonists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A.B. Frost was renowned for his sporting scenes, particularly hunting and fishing, and his humorous depictions of rural American life. This familial environment undoubtedly provided young John with his earliest exposure to artistic techniques, narrative composition, and the discipline required of a professional artist.

Growing up under the tutelage of such a prominent artistic figure, John Frost's initial artistic inclinations were naturally nurtured at home. His father's keen eye for detail, his ability to capture movement and character, and his understanding of the American landscape would have been formative influences. While A.B. Frost's style was primarily illustrative and rooted in realism, the foundational skills in drawing and observation John acquired were crucial for his later development, regardless of the stylistic path he would eventually choose. This early, informal training provided a solid bedrock upon which his more formal education would build.

The artistic milieu of Philadelphia at the turn of the century was also significant. The city boasted institutions like the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, which had a strong tradition of American painting, influenced by figures like Thomas Eakins. While Frost's primary early guidance came from his father, the broader artistic currents of the time, including the burgeoning interest in Impressionism that was taking hold in America, would have been part of the cultural atmosphere.

Parisian Sojourn and the Embrace of Impressionism

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons and immerse himself in the epicenter of contemporary art, John Frost, like many aspiring American artists of his generation, traveled to Paris. This was a pivotal period in his development. In Paris, he enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school that attracted students from around the world, offering an alternative to the more rigid École des Beaux-Arts. The Académie Julian was known for its roster of influential instructors and its more liberal approach to teaching.

At the Académie Julian, Frost studied under esteemed academic painters such as Jean-Paul Laurens. Laurens was a master of historical and religious painting, known for his dramatic compositions and somber palette, representing the strong academic tradition. Exposure to such rigorous academic training would have honed Frost's skills in draftsmanship, anatomy, and composition, providing a classical counterpoint to the Impressionist influences he would soon embrace more fully.

Perhaps more significantly for his stylistic evolution, Frost also studied with the American expatriate artist Richard E. Miller. Miller was a prominent member of the Giverny Colony of American Impressionists, artists who gathered near Claude Monet's home and were deeply influenced by his work and the principles of French Impressionism. Miller himself was known for his decorative paintings of women in sun-dappled interiors or gardens, rendered with a bright palette and broken brushwork. Studying with Miller provided Frost with direct exposure to Impressionist techniques and philosophies from a practitioner who had absorbed them firsthand.

During his time in France, Frost would have inevitably been immersed in the legacy and ongoing vibrancy of Impressionism. The works of masters like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas were transforming the way artists perceived and depicted the world. The emphasis on capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, painting en plein air (outdoors), using unmixed colors applied in small dabs to create optical vibrancy, and depicting everyday life or landscape rather than purely historical or mythological subjects – these were the hallmarks of the movement that deeply resonated with Frost. His time in Giverny, a hub for American artists like Theodore Robinson, Willard Metcalf, and his future friend Guy Rose, further solidified this Impressionist leaning.

Health Challenges and a Shift in Scenery

John Frost's promising artistic career was unfortunately shadowed by persistent health issues. He contracted tuberculosis, a widespread and often fatal disease in that era, which would significantly impact his life and productivity. Around 1912, seeking a cure or at least an environment conducive to recovery, Frost traveled to Davos, Switzerland. Davos was renowned for its sanatoria and the belief that its high-altitude, fresh mountain air was beneficial for respiratory ailments. He remained there for treatment until approximately 1914.

This period, while focused on health, likely still offered opportunities for observation and perhaps some artistic work, as the Alpine landscapes were dramatically different from what he had previously encountered. The clear light and majestic scenery of Switzerland, though not his primary subject matter later, may have subtly influenced his appreciation for atmospheric effects.

Upon returning to the United States, Frost initially settled in New York. He continued to paint, attempting to establish his career. However, the climate of the East Coast was not ideal for his compromised health. The dampness and cold winters likely exacerbated his condition, prompting a search for a more favorable environment. This search would ultimately lead him to a place that would become central to his artistic identity: California.

The California Years: A New Light, A New Canvas

In 1918, driven by the need for a drier, warmer climate to manage his tuberculosis, John Frost made the life-altering move to Pasadena, California. This relocation proved to be immensely beneficial not only for his health but also for his art. Southern California at this time was experiencing a burgeoning art scene, particularly centered around Impressionism, often referred to as California Impressionism or California Plein-Air Painting. The region's unique geography – with its dramatic deserts, rugged mountains, sun-drenched coastline, and vibrant flora – offered a wealth of inspiration for artists.

The light in California was a revelation. It was different from the softer, more diffused light of the East Coast or Europe. It was clearer, brighter, and capable of producing intense colors and sharp contrasts, particularly in the arid desert regions. This environment was perfectly suited to the Impressionist preoccupation with light and its effects. Frost, already steeped in Impressionist principles, found in California an ideal subject for his artistic explorations.

In Pasadena, Frost became closely associated with Guy Rose, another prominent California Impressionist. Rose, who had also spent considerable time in Giverny and was deeply influenced by Monet, became a friend and mentor to Frost. They often embarked on painting expeditions together, sharing insights and techniques. Rose's mature Impressionist style, characterized by a delicate palette and refined compositions, undoubtedly influenced Frost, though Frost developed his own distinct voice.

The artistic community in Southern California was vibrant, with figures like William Wendt, known as the "dean" of Southern California landscape painters for his robust, structural depictions; Granville Redmond, a deaf artist celebrated for his Tonalist scenes as well as his vibrant poppy fields; Edgar Payne, famous for his majestic Sierra Nevada landscapes and dramatic seascapes; and Alson S. Clark, another artist with Giverny experience who captured the sunlit architecture and landscapes of California. Frost became an integral part of this milieu, contributing his unique perspective.

Artistic Style and Dominant Themes

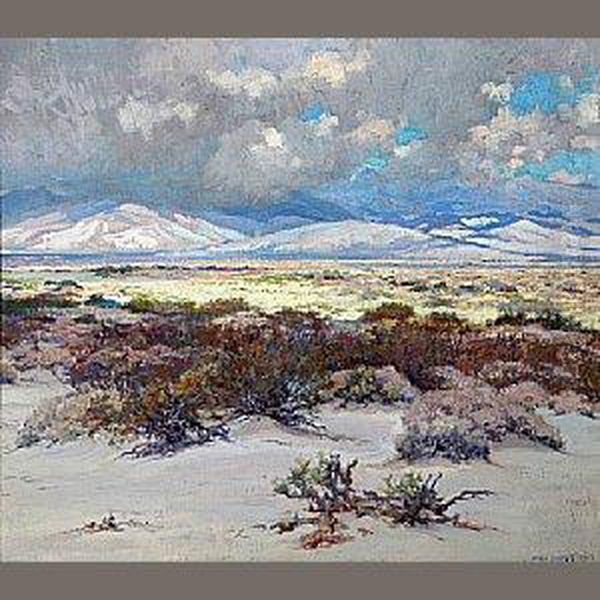

John Frost's artistic style is firmly rooted in Impressionism, yet it bears his individual stamp, shaped by his training, his personal vision, and the specific landscapes he chose to depict. His work is characterized by a bright, often high-keyed palette, reflecting the intense sunlight of the American West. He employed broken brushwork – short, distinct strokes of color – to capture the vibrancy of light and the texture of the landscape. This technique allowed colors to mix optically in the viewer's eye, creating a sense of immediacy and luminosity.

A key feature of Frost's work is his masterful handling of atmosphere. He was adept at conveying the haze of a distant mountain range, the shimmering heat of the desert, or the soft light of a coastal scene. His landscapes are not mere topographical records; they are imbued with a sense of mood and place, capturing the ephemeral qualities of a particular moment in time. He often favored panoramic views, allowing him to explore the expansive vistas of California.

His primary themes were the diverse landscapes of California and the Southwest. He was particularly drawn to the desert regions, such as the area around Palm Springs, including Chino Canyon. His desert scenes are notable for their depiction of the unique desert flora, the stark beauty of the arid terrain, and the dramatic play of light and shadow across the mountains and canyons. He also painted the rolling hills, majestic mountains like the Sierra Nevada, and the picturesque coastline of California. Small towns and rural scenes also occasionally featured in his work, always rendered with his characteristic sensitivity to light and color.

While clearly an Impressionist, Frost's work sometimes shows a structural solidity that perhaps reflects his academic training or the influence of Post-Impressionist ideas that were also current. His compositions are generally well-balanced, guiding the viewer's eye through the scene with a clear sense of depth and space. He shared with other California Impressionists a deep reverence for nature, and his paintings often evoke a sense of tranquility and awe in the face of the natural world.

Representative Works: Capturing the Essence of the West

Several paintings stand out as representative of John Frost's artistic achievements and his contribution to California Impressionism.

"Chino Canyon" (1925) is one of his most celebrated works. This painting depicts the rugged beauty of the desert landscape near Palm Springs. Frost masterfully captures the intense sunlight on the rocky canyon walls, using a palette of warm earth tones, purples, and blues to convey the arid atmosphere and the distant haze. The brushwork is confident and expressive, defining the forms of the landscape while simultaneously conveying the shimmering quality of the desert light. The composition leads the eye deep into the canyon, creating a sense of vastness and solitude. This work exemplifies his ability to translate the unique character of the California desert onto canvas with both accuracy and poetic sensibility.

"A View of the Coast from Clifftop" (date unknown, but typical of his California period) showcases another facet of his engagement with the Californian environment. In such coastal scenes, Frost would typically employ a cooler palette, capturing the blues and greens of the Pacific Ocean and the varied colors of the coastal bluffs. His skill in rendering atmospheric perspective would be evident in the way the distant coastline recedes into a soft haze. The play of sunlight on the water and the textures of the cliffs would be rendered with his characteristic Impressionistic touch, conveying the fresh, breezy atmosphere of the seaside.

"Fly Fishing Lesson off the Back Porch" (1919) offers a glimpse into a more intimate, perhaps narrative scene, possibly influenced by his father's sporting art, yet rendered in Frost's Impressionist style. While primarily known for his pure landscapes, this work suggests a versatility and an ability to incorporate figures into his light-filled environments. The focus would still be on the effects of light – perhaps dappled sunlight filtering through trees, reflections on water – and the relaxed, leisurely atmosphere of the scene.

These works, among others, demonstrate Frost's commitment to en plein air painting and his ability to capture the specific light and color of the American West. His paintings are not just depictions of places, but evocations of the experience of being in those landscapes.

Later Career and Foray into Sporting Art

In the later years of his relatively short career, John Frost began to explore themes reminiscent of his father's work, notably sporting art. He produced a number of paintings depicting hunting and fishing scenes. This thematic shift might have been a nod to his artistic heritage, a personal passion, or perhaps an attempt to reach a different segment of the art market.

These sporting scenes were rendered with the same Impressionistic sensibility that characterized his landscapes. He applied his understanding of light, color, and atmosphere to these dynamic subjects, capturing the excitement of the chase or the quiet concentration of an angler. The figures in these scenes are typically well-integrated into their natural surroundings, with the landscape itself playing a crucial role in the composition and mood.

These works were well-received, particularly by collectors of sporting art, and they demonstrate Frost's versatility as a painter. Even when tackling subjects with a strong narrative element, his primary concern remained the visual and atmospheric qualities of the scene. The high clarity and vibrant colors he employed in these pieces made them particularly appealing. His ability to combine the dynamism of sporting activities with the nuanced beauty of the natural environment set these works apart.

Despite this exploration of new themes, landscape painting remained central to his oeuvre. His deep connection to the Californian environment continued to provide him with his primary source of inspiration.

Legacy and Enduring Recognition

John Frost's life was tragically cut short when he succumbed to tuberculosis in Pasadena in 1937, at the age of only 47. His premature death undoubtedly limited the full arc of his artistic development and the volume of work he might have produced. Nevertheless, in his relatively brief career, he made a significant contribution to American art, particularly within the California Impressionist movement.

His works were exhibited during his lifetime at prominent venues, including the Stendahl Galleries in Los Angeles, which played a crucial role in promoting California Impressionism, and the Ambassador Hotel, another key exhibition space. Posthumously, his paintings have continued to be appreciated and are held in private collections and some museum collections.

The auction market for his works reflects a sustained interest and appreciation for his talent. Paintings like "Chino Canyon" and "A View of the Coast from Clifftop" command respectable prices, indicative of his standing among California Impressionists. Collectors value his paintings for their luminous quality, their evocative portrayal of the Western landscape, and their skillful execution.

John Frost's legacy lies in his ability to synthesize the principles of French Impressionism with the unique visual character of the American West. He was part of a generation of artists who helped to define a distinctly American response to Impressionism, adapting its techniques and philosophies to new subjects and new light. His paintings of the California deserts, mountains, and coastline are enduring testaments to his artistic vision and his love for the landscapes that inspired him. He remains an important figure for those studying the rich history of California art and the broader story of American Impressionism. His work invites viewers to see the familiar landscapes of the West through a lens of heightened color, light, and atmospheric beauty.