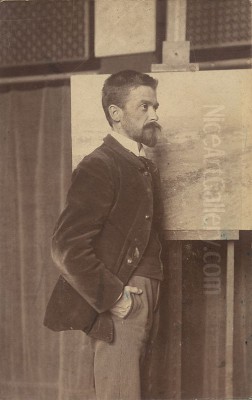

Theodore Robinson stands as a pivotal figure in the history of American art, celebrated primarily for his role in introducing and adapting French Impressionism for an American audience. Living a relatively short life from 1852 to 1896, Robinson forged a unique path, deeply influenced by his experiences abroad, particularly his close association with the master Impressionist Claude Monet. Yet, his work retained a distinctly American sensibility, blending the vibrant light and broken color of Impressionism with a foundational respect for form and structure rooted in his academic training and native traditions. His landscapes and figural scenes capture moments of quiet beauty, reflecting both the influence of his French contemporaries and his own lyrical interpretation of the world around him.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Theodore Robinson was born on June 3, 1852, in Irasburg, Vermont. His family background was modest; his father, Elijah Robinson, was a Methodist minister, and his mother, Ellen Brown Robinson, provided a supportive environment for his burgeoning artistic interests. The family did not remain in Vermont for long, moving westward when Theodore was still a young child, eventually settling in Evansville, Wisconsin. It was here, amidst the landscapes of the American Midwest, that Robinson's artistic inclinations began to take shape, encouraged particularly by his mother.

His formal art education began relatively late compared to some of his European counterparts. Around 1869, at the age of seventeen, he traveled to Chicago to briefly study at the Chicago Academy of Design (a precursor to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago). However, his studies were cut short due to persistent health problems, specifically severe asthma, which would plague him throughout his life and ultimately contribute to his early death. This chronic condition often dictated his movements and limited his physical endurance, yet it rarely dampened his artistic drive.

New York Studies and Academic Foundations

Forced to return home from Chicago due to his health, Robinson did not abandon his artistic ambitions. By 1874, he had made his way to New York City, the burgeoning center of the American art world. There, he enrolled in the prestigious National Academy of Design, immersing himself in the traditional academic curriculum that emphasized drawing, anatomy, and composition. He also likely attended classes at the newly formed Art Students League, an institution founded by students seeking a more progressive alternative to the Academy.

During his New York years, Robinson honed his skills in draftsmanship and began to establish himself within the city's artistic community. His early work from this period reflects the prevailing tastes, leaning towards Realism and the detailed rendering characteristic of American painting at the time. He associated with other young artists, absorbing the influences available to him, but already showing a sensitivity to landscape and natural effects that hinted at his future direction. This foundational training provided him with a technical solidity that would underpin even his most impressionistic later works.

Parisian Immersion and Broadening Horizons

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Robinson recognized the necessity of European study to fully develop his talents and gain international recognition. In 1876, he embarked for Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. This move marked a crucial turning point in his career. He sought out instruction from leading academic painters, enrolling first in the atelier of Emile-Auguste Carolus-Duran, a fashionable portraitist known for his painterly technique influenced by Velázquez.

Subsequently, Robinson studied under Jean-Léon Gérôme at the renowned École des Beaux-Arts. Gérôme was a staunch defender of academic tradition, famous for his meticulously detailed historical and Orientalist scenes. Studying under Gérôme provided Robinson with rigorous training in drawing and composition, reinforcing the academic discipline he had begun in New York. While this training might seem antithetical to his later Impressionist leanings, it equipped him with a strong sense of structure and form that he never fully abandoned.

During his time in France, Robinson also spent time outside Paris, notably in Grez-sur-Loing, a village near the Forest of Fontainebleau that attracted an international colony of artists. This brought him into contact with the lingering influence of the Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-François Millet and Camille Corot, who emphasized direct observation of nature, rural subjects, and atmospheric mood. It was in Grez that Robinson formed a friendship with the Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson, another resident of the artists' colony.

Early Career and Transatlantic Crossings

Robinson's initial years in France were marked by diligent study and the gradual absorption of diverse influences. He exhibited works at the Paris Salon, the official juried exhibition, gaining some recognition. He traveled, spending time in Venice and Bologna in 1879, further broadening his artistic horizons. He made several trips back and forth across the Atlantic, maintaining connections in both the American and French art worlds.

Upon returning to the United States periodically, Robinson sought commissions and teaching opportunities to support himself. An important early collaboration occurred in 1881 when he worked as an assistant to the prominent American artist John La Farge on decorative projects, including murals. La Farge, known for his sophisticated color sense and interest in stained glass, may have further stimulated Robinson's sensitivity to light and hue. These experiences helped Robinson integrate his European learning with the practical demands of the American art market.

The Giverny Revelation: Monet and Impressionism

The most transformative period in Robinson's artistic life began in the late 1880s with his discovery of Giverny, a small village on the Seine River northwest of Paris. Giverny was home to Claude Monet, the leading figure of French Impressionism, who had settled there in 1883. Drawn by the picturesque landscape and the presence of Monet, Giverny became a magnet for artists, particularly Americans. Robinson first visited in 1887 and returned repeatedly, spending extended periods there between 1888 and 1892.

Robinson developed a close personal and professional relationship with Monet. He became one of the few American artists admitted into Monet's inner circle, often dining with the Monet family and discussing art with the master himself. While Monet did not take formal pupils, he offered advice and critiques, profoundly influencing Robinson's understanding and application of Impressionist principles. Robinson meticulously documented their conversations and his own experiments in his diaries, providing invaluable insight into his artistic evolution and Monet's methods.

Under Monet's influence, Robinson fully embraced the Impressionist aesthetic. He adopted a brighter palette, used broken brushwork to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, and committed himself to painting en plein air (outdoors). He focused on the interplay of sunlight and shadow, the reflections on water, and the vibrant colors of the French countryside. His Giverny paintings often depict the local landscape, village scenes, and figures integrated within nature, bathed in the characteristic light of the region.

Adapting Impressionism: A Personal Style

Despite the profound impact of Monet and Giverny, Theodore Robinson did not simply mimic the French master. He adapted Impressionism to his own temperament and artistic background. Compared to Monet's often dazzling and dissolving forms, Robinson's work generally retained a greater sense of underlying structure and solidity, a legacy of his academic training under Gérôme. His figures, while painted with Impressionist techniques, often possess a weight and definition that distinguishes them from Monet's more integrated figures.

Robinson's color palette, while significantly brightened, could also be more subdued and tonal at times, reflecting perhaps a more reserved, lyrical sensibility. His brushwork, though looser and more visible than in his earlier work, was often applied with a delicate touch. He was particularly drawn to capturing specific times of day and weather conditions, exploring the subtle nuances of light rather than solely its most brilliant effects. This resulted in a style that was recognizably Impressionist yet possessed a distinct, personal quality – an American interpretation of the French movement.

His subjects often focused on the quiet, everyday life of rural France – women working in fields, farm buildings nestled in the landscape, tranquil river views. Even when painting the same motifs as Monet, such as haystacks or the Seine, Robinson brought his own perspective, often choosing different viewpoints or emphasizing different aspects of the scene. This ability to absorb influence while maintaining individuality is a hallmark of his artistic maturity.

Key Works from the Giverny Period

Robinson's time in Giverny was highly productive, yielding some of his most celebrated works. The Valley of the Seine, from the Hills of Giverny (often identified with titles like The Valley of Arconville) exemplifies his mastery of the Impressionist landscape. It showcases a panoramic view bathed in sunlight, rendered with vibrant greens, blues, and yellows, and characteristic broken brushwork capturing the atmospheric haze.

Another significant work is The Wedding March (1892), painted to commemorate the marriage of Monet's stepdaughter, Suzanne Hoschedé, to the American painter Theodore Earl Butler. This painting captures the procession moving through the village, demonstrating Robinson's ability to handle complex figural compositions within an Impressionist framework, balancing individual figures with the overall play of light and color.

Other notable paintings from this era include La Débâcle (1892), depicting the breaking up of ice on the Seine, a subject also tackled by Monet, but rendered with Robinson's characteristic sensitivity to atmospheric nuance. Works like Willows (also known as By the River) show his skill in capturing the shimmering effect of light filtering through foliage and reflecting on water, using a high-keyed palette and fluid brushstrokes. These paintings cemented his reputation as a leading American Impressionist.

Return to America: Teaching and Influence

In 1892, Robinson returned to the United States for the final time, bringing with him the mature Impressionist style he had forged in Giverny. He became an important conduit for transmitting Impressionist ideas back to his homeland, not only through his paintings but also through teaching. He secured several teaching positions, sharing his knowledge and enthusiasm for the new style with American students.

He taught at the Brooklyn Art Association, conducted summer classes at Napanoch, New York, near the Delaware and Hudson Canal (a subject of many of his later paintings), and later at Evelyn College (then the women's coordinate college at Princeton University). He also taught briefly at the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Through his teaching, he influenced a younger generation of American artists, helping to popularize Impressionism beyond the small circle of artists who had studied abroad.

Robinson became part of a growing movement of American Impressionism, which included artists like Childe Hassam, John Henry Twachtman, and J. Alden Weir, many of whom had also spent time in France and were adapting Impressionist techniques to American subjects and light. Robinson associated with these artists, exhibiting alongside them and contributing to the gradual acceptance of Impressionism by American collectors and institutions. He was elected to the Society of American Artists, a more progressive group than the National Academy of Design.

Robinson's Mature American Style

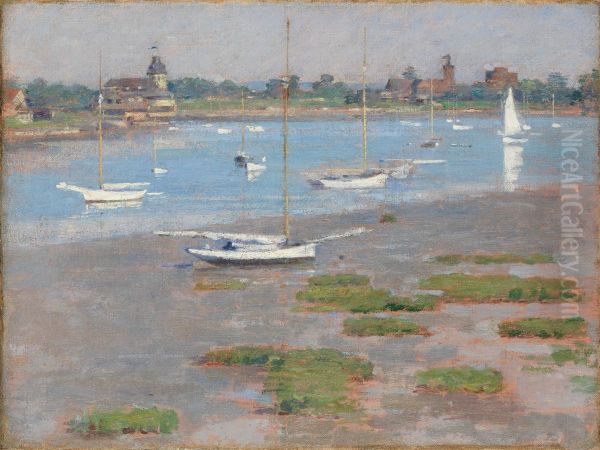

During his final years in America, Robinson continued to paint prolifically, applying his Impressionist approach to American landscapes. He found subjects in the countryside of Vermont, Connecticut, and New York, particularly along the Delaware and Hudson Canal. Works from this period, such as Port Ben, Delaware and Hudson Canal (1893) and Low Tide, Riverside Yacht Club (1894), demonstrate his continued fascination with light, water, and atmosphere, now applied to distinctly American scenes.

His American landscapes often possess a quiet, pastoral quality. While still employing Impressionist techniques, some critics detect a subtle shift, perhaps a return to slightly more solid forms or a tonal quality reminiscent of American Luminism or the works of Winslow Homer, another major American painter navigating realism and light. He continued to integrate figures into his landscapes, often depicting women engaged in quiet domestic or leisure activities, rendered with sensitivity and grace.

His commitment to plein air painting remained strong, even as his health declined. He sought out locations that offered compelling motifs and allowed him to work outdoors, capturing the specific character of American light and landscape. His late works confirm his status as a major interpreter of the American scene through an Impressionist lens.

Artistic Circle and Collaborations

Beyond his seminal relationship with Claude Monet, Robinson interacted with a wide circle of artists and writers on both sides of the Atlantic. His early collaboration with John La Farge provided valuable experience in decorative work. In France, particularly in Giverny and Grez-sur-Loing, he was part of a vibrant international community. Besides Monet, he knew American painters like Willard Metcalf, Theodore Earl Butler, John Leslie Breck, and Lilla Cabot Perry, who were also exploring Impressionism in Giverny.

His friendship with Robert Louis Stevenson in Grez highlights the cross-pollination between artistic and literary circles during this period. Back in the United States, he was connected with fellow American Impressionists like Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, and John Henry Twachtman, sharing exhibition venues and contributing to the collective effort to establish the new style. He also maintained friendships with artists working in more traditional styles, reflecting his broad engagement with the art world of his time. These connections enriched his artistic life and helped position him within the key developments of late 19th-century art.

Health Struggles and Final Years

Theodore Robinson's life and career were constantly shadowed by his chronic asthma. This condition frequently interrupted his work, forced him to seek out climates thought to be beneficial, and likely contributed to a sense of urgency in his artistic production. Despite these challenges, he maintained a rigorous work ethic and a deep commitment to his art. His diaries reveal his ongoing struggles with health, finances, and occasional artistic self-doubt, painting a portrait of a dedicated artist persevering against considerable odds.

In the mid-1890s, his health deteriorated more significantly. He spent time in Vermont, hoping the mountain air would provide relief. However, his condition worsened. He returned to New York City, where he died suddenly following an acute asthma attack on April 2, 1896, at the tragically young age of 44. He passed away in the apartment of his cousin, just as he was achieving wider recognition and seemed poised for continued artistic growth.

Legacy and Recognition

Despite his short career, Theodore Robinson left an indelible mark on American art. He was one of the very first American artists to fully understand and assimilate French Impressionism, and crucially, to adapt it into a personal style suited to American sensibilities. His close relationship with Monet provided him with unparalleled insight, which he effectively translated into his own work and shared through his teaching.

His paintings are admired for their lyrical beauty, their sensitive rendering of light and atmosphere, and their harmonious blend of Impressionist technique with a respect for form. He successfully bridged the gap between European modernism and American tradition, creating works that felt both innovative and grounded. His influence extended to his students and fellow artists, helping to shape the course of American Impressionism.

Recognition of his importance grew steadily after his death. A memorial exhibition was held shortly after he passed away. A major retrospective organized by the Brooklyn Museum in 1946, fifty years after his death, solidified his reputation. Another significant traveling exhibition organized by the Baltimore Museum of Art in 1973 further cemented his place in the canon of American art. Today, his works are held in major museum collections across the United States, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Phillips Collection, the Terra Foundation for American Art, the White House Collection, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, among many others.

Conclusion: A Gentle Pioneer

Theodore Robinson's contribution to American art lies in his role as a sensitive interpreter and pioneer. He navigated the complex currents of late 19th-century art, absorbing the revolutionary techniques of French Impressionism through direct contact with its greatest master, Claude Monet, yet filtering them through his own artistic vision and American background. His paintings, characterized by their gentle light, harmonious color, and quiet observation of nature and rural life, offer a unique and enduring perspective. Though his life was cut short, his dedication to capturing the beauty of the world around him, his willingness to embrace new ideas, and his ability to forge a personal style ensure his legacy as a crucial and beloved figure in the story of American Impressionism. He remains a testament to the fruitful dialogue between American and European art at a time of significant transformation.