The Honourable John Maler Collier OBE ROI RP stands as a significant figure in the landscape of British art during the late Victorian and Edwardian periods. Born on January 27, 1850, and passing away on April 11, 1934, Collier carved a distinct niche for himself as both a painter and a writer, becoming particularly renowned for his compelling portraits executed in a style deeply influenced by, yet distinct from, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His work bridged the academic traditions of the era with a modern psychological insight, leaving behind a rich legacy of canvases that continue to engage viewers today.

Collier emerged from a family marked by intellectual and social prominence. His grandfather, John Collier, was a Quaker merchant who rose to become a Member of Parliament. His father, Robert Porrett Collier, achieved distinction as the 1st Baron Monkswell, serving as Lord Justice of Appeal and becoming a member of the Royal Society of British Artists. This environment undoubtedly fostered an appreciation for culture and public life, providing a foundation for Collier's own pursuits in the arts and letters. His brother, the 2nd Baron Monkswell, was Under-Secretary of State for War, further highlighting the family's standing.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

John Maler Collier received his formal education at Eton College, a traditional path for young men of his social standing. However, his inclination towards art soon became apparent. Seeking rigorous training, he initially studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London under Sir Edward Poynter, a prominent figure in the academic art establishment known for his classical subjects and meticulous technique. Poynter's emphasis on draughtsmanship would have provided a solid grounding.

Seeking broader European perspectives, Collier travelled abroad for further study. In 1875, he enrolled at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, a centre known for its painterly realism and robust technique, contrasting somewhat with the more linear emphasis found in Paris at the time. Following his time in Germany, Collier moved to Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. There, he entered the atelier of Jean-Paul Laurens, a respected painter of historical and religious subjects, known for his dramatic compositions and sombre palette. This combination of British, German, and French training equipped Collier with a versatile technical skill set.

The Pre-Raphaelite Influence and Artistic Style

While not a formal member of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which had largely dissolved as a cohesive movement by the time Collier began his career, his work undeniably absorbed many of its core tenets. He shared their commitment to serious subject matter, often drawn from literature, mythology, and history, and their dedication to truth to nature, rendered with meticulous detail and often vibrant colour. His approach, however, tended towards a smoother finish and a more conventional sense of composition than the sometimes starker, more radical early works of the Brotherhood.

Key figures associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, particularly Sir John Everett Millais, exerted a noticeable influence on Collier. Millais, a founding member of the PRB who later became a highly successful and respected President of the Royal Academy, demonstrated how Pre-Raphaelite principles could be adapted to achieve popular acclaim, especially in portraiture and narrative painting. Collier clearly learned from Millais's example, blending detailed observation with accessible storytelling.

Another significant influence was Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, a Dutch-born painter who settled in London and achieved immense fame for his depictions of classical antiquity. Alma-Tadema's polished technique, archaeological precision, and sensuous rendering of textures like marble and fabric resonated with Collier's own inclinations. Collier's father, Lord Monkswell, even commissioned a work from Alma-Tadema, indicating a family appreciation for his style. Collier adopted a similar clarity of form and careful rendering, though often applied to different subject matter.

Collier's own style is characterized by strong draughtsmanship, a clear, often bright palette, and a confident handling of oil paint. He paid close attention to the effects of light and shadow, using them to model form effectively and create mood. While grounded in realism, his works often possess a heightened sense of drama or psychological intensity, particularly evident in his narrative paintings and portraits of notable personalities.

A Celebrated Portraitist

Portraiture formed the bedrock of John Maler Collier's career and reputation. He became one of the most sought-after portrait painters of his generation, capturing the likenesses of prominent figures across society, including politicians, scientists, artists, writers, and members of the aristocracy. His success in this field was cemented by his regular exhibitions at the Royal Academy of Arts and his active involvement with the Royal Society of Portrait Painters (RSPP).

Collier was a founding member of the RSPP in 1891 and later served as its Vice-President for two decades, from 1909 until his death. This position underscored his standing within the portrait painting community. He was known for his ability to produce not just accurate likenesses, but also insightful character studies. His portraits often convey a sense of the sitter's personality and social standing through pose, expression, and carefully chosen accessories or backgrounds.

Among his most notable sitters were leading intellectuals and figures of the age. He painted two portraits of his father-in-law, the eminent biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his staunch defence of evolutionary theory. He also captured the likenesses of Charles Darwin himself, the writer Rudyard Kipling, Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, the actor J.L. Toole, and numerous other distinguished individuals. These commissions placed him at the heart of British intellectual and cultural life.

His approach to portraiture was often compared to that of his contemporaries. While perhaps lacking the dazzling brushwork of John Singer Sargent or the intense psychological probing of Hubert von Herkomer, Collier offered a reliable, dignified, and often penetrating portrayal that appealed greatly to the establishment figures who commissioned him. His style represented a solid, accomplished academic realism infused with Pre-Raphaelite clarity. He received the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1920 for his contributions.

Narrative and Subject Pictures

Beyond portraiture, Collier dedicated significant energy to narrative and subject paintings, often drawing inspiration from history, mythology, literature, and contemporary life. These works allowed him greater freedom in composition and thematic exploration, and they include some of his most famous and debated canvases.

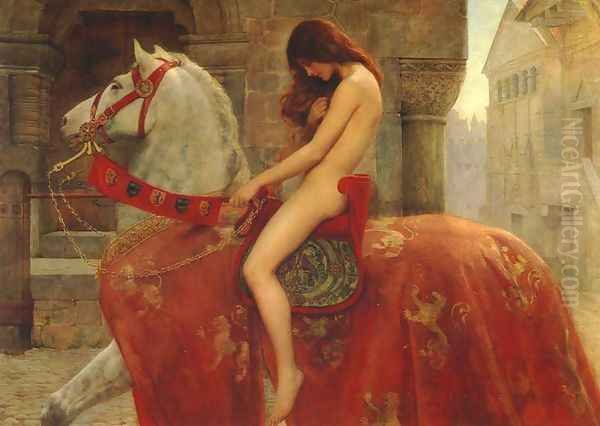

Perhaps his most widely recognized painting is Lady Godiva (c. 1898), now housed in the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry. Depicting the legendary Anglo-Saxon noblewoman riding naked through the streets of Coventry to protest her husband's oppressive taxes, the painting is a striking image of vulnerability and defiance. Collier renders Godiva with sensitivity, emphasizing her modesty and resolve against a detailed backdrop of medieval architecture. The work captures the Victorian fascination with historical romance and moral courage.

Another major historical work is The Death of Cleopatra (1890). Here, Collier tackles the dramatic final moments of the Egyptian queen. The painting showcases his skill in rendering luxurious textures – fabrics, jewels, and flesh – and his interest in historical detail, incorporating elements suggestive of Egyptian artifacts. The composition is theatrical, focusing on the languid figure of Cleopatra after being bitten by the asp, attended by her grieving handmaidens. It reflects the 19th-century European fascination with Orientalist themes and dramatic historical episodes, comparable in ambition to works by French academic painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme.

Collier also explored Greek mythology, notably in his two paintings of Clytemnestra. The first, from 1882, shows Agamemnon's vengeful wife after the murder of her husband, axe in hand, standing grimly in a doorway. A later version, painted around 1914, depicts her awaiting Agamemnon's return, a more psychologically tense portrayal informed perhaps by newer archaeological discoveries from Crete, reflecting an ongoing engagement with classical themes updated with contemporary knowledge. His Priestess of Delphi (1891) similarly delves into the ancient world, depicting the oracle in a trance-like state, showcasing his ability to convey mystery and psychological intensity.

A distinctive aspect of Collier's narrative work is his engagement with the "problem picture" genre, popular in the late Victorian era. These paintings depicted ambiguous social or domestic situations, inviting viewers to speculate on the narrative and the characters' motivations. The Fallen Idol (1902), sometimes known as The Cheat, is a prime example. It shows a tense confrontation between a husband and wife, where the wife appears to have confessed to infidelity, leaving the viewer to ponder the consequences. Similarly, The Prodigal Daughter (c. 1903) depicts the dramatic return of a wayward young woman to her shocked family, her fashionable attire contrasting with the sombre domestic setting. These works touched upon contemporary social anxieties and moral dilemmas.

His historical painting The Last Voyage of Henry Hudson (exhibited 1881) tackles a theme of exploration and betrayal, depicting the explorer cast adrift by his mutinous crew in the Arctic. It’s a powerful image of isolation and despair, rendered with attention to the harsh environment and the emotional state of the figures, demonstrating his versatility in subject matter.

Technique and Method

John Maler Collier was not only a practitioner but also a thoughtful commentator on the art of painting. He authored several books on technique that offer insight into his methods and the principles he valued. These include A Primer of Art (1882), A Manual of Oil Painting (1886), and The Art of Portrait Painting (1905). These manuals suggest a methodical and rational approach to his craft.

His writings emphasize the importance of accurate drawing as the foundation of good painting, reflecting his academic training. He advocated for a direct approach to oil painting, often working alla prima (wet-on-wet) or with minimal underpainting, particularly in portraits, to achieve freshness and vibrancy. He stressed the careful observation of colour and tone in relation to light, aiming for a truthful representation of appearances.

His Manual of Oil Painting provides practical advice on materials, colour mixing, and application techniques. The Art of Portrait Painting delves into the specific challenges of capturing likeness and character, discussing composition, lighting, and the relationship between artist and sitter. These texts reveal Collier as a proponent of sound craftsmanship and objective representation, aligning him with the realistic traditions of the 19th century. He believed that sentiment and emotion in painting should arise naturally from the truthful depiction of the subject, rather than through exaggerated effects.

His studio practice likely involved preliminary sketches and studies, particularly for complex narrative compositions. He would have worked extensively from models, paying close attention to anatomy, drapery, and expression. The high level of finish and detail in many of his works indicates a patient and meticulous working process, balancing the desire for accuracy with the need for artistic effect.

Contemporaries and Context

John Maler Collier operated within a vibrant and complex British art world. The late Victorian and Edwardian eras saw the coexistence of various artistic movements and styles. The influence of the Pre-Raphaelites, including figures like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, and Edward Burne-Jones, continued to be felt, particularly in subject matter and decorative richness. Simultaneously, academic classicism, championed by artists like Lord Leighton and Sir Edward Poynter, held sway at the Royal Academy.

Aestheticism, with its emphasis on "art for art's sake," offered another alternative, most famously represented by James McNeill Whistler, whose tonal harmonies and suggestive forms contrasted sharply with Collier's clear realism. The rise of Impressionism in France also began to influence British artists, although its impact on established figures like Collier was limited. He remained largely committed to a detailed, representational style throughout his career.

Within the realm of portraiture, Collier competed with and worked alongside major figures. John Singer Sargent, an American expatriate, dominated the field with his dazzling brushwork and sophisticated portrayals of high society. German-born Hubert von Herkomer was another highly successful portraitist and subject painter, known for his social realism and vigorous technique. George Frederic Watts, an older artist, created allegorical portraits and "historical" paintings imbued with moral seriousness. Frank Dicksee continued the tradition of romantic and historical subjects with a polished finish.

Collier navigated this landscape successfully, maintaining a strong presence at the Royal Academy exhibitions for over fifty years. His style, while perhaps less innovative than some, offered a reassuring blend of traditional skill and modern sensibility that appealed to patrons and the public alike. He represented a mainstream, highly competent strand of British art that valued narrative clarity, technical proficiency, and dignified representation.

Marriage, Family, and Social Circle

John Maler Collier's personal life was notably intertwined with one of the most prominent intellectual families of the era – the Huxleys. In 1879, he married Marian (Mady) Huxley, herself a talented painter who had studied alongside Collier at the Slade School. She was the daughter of Thomas Henry Huxley, the renowned biologist and advocate for Darwin's theories. This marriage connected Collier directly to a circle of leading scientists, writers, and thinkers.

Tragically, Marian died of pneumonia in 1887, leaving Collier with their young daughter, Joyce. Joyce Collier would later follow in her parents' footsteps, becoming a respected portrait miniaturist and exhibiting at the Royal Academy.

Following Marian's death, Collier developed a close relationship with her younger sister, Ethel Gladys Huxley. However, marriage to a deceased wife's sister was illegal in England at that time under ecclesiastical law. Determined to marry, Collier and Ethel travelled to Norway, where such marriages were permitted, and wed there in 1889. This act required a degree of social courage and highlighted the restrictive nature of English marriage laws, which were only changed by the Deceased Wife's Sister's Marriage Act in 1907.

His marriage to Ethel produced two children: a daughter, and a son, Sir Laurence Collier, who became the British Ambassador to Norway from 1941 to 1951. The Huxley connection remained central to Collier's social and intellectual life, placing him within a milieu that valued rationalism, scientific progress, and public discourse – values that arguably informed the clarity and directness of his artistic approach.

Later Life and Legacy

John Maler Collier remained a productive and respected artist well into the 20th century. He continued to exhibit regularly and undertake portrait commissions. His style, while established in the Victorian era, retained its appeal for many patrons seeking traditional, well-crafted likenesses and narrative paintings. He adapted somewhat to changing tastes but remained fundamentally committed to the principles of realism and strong narrative content that had defined his career.

He continued his involvement with the Royal Society of Portrait Painters as Vice-President and maintained his connections with the Royal Academy. His writings on art technique also ensured his influence extended to aspiring artists seeking practical guidance. He lived to the age of 84, passing away in his London home in Hampstead on April 11, 1934.

Today, John Maler Collier is remembered as a leading figure of late Victorian and Edwardian art. While perhaps overshadowed in critical discourse by more avant-garde movements, his work retains considerable appeal for its technical skill, narrative interest, and insightful portraiture. His paintings offer a valuable window into the tastes, values, and personalities of his era.

His works are held in numerous public collections in the United Kingdom and beyond. Key examples can be found in Tate Britain, the National Portrait Gallery in London (which holds many of his portraits of eminent figures), the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, Manchester Art Gallery, the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum in Coventry, and Southampton City Art Gallery, among others. These collections ensure that his contribution to British art remains accessible to contemporary audiences.

Conclusion

The Honourable John Maler Collier navigated the complex art world of late 19th and early 20th century Britain with considerable success. Rooted in academic training yet deeply influenced by the colour and detail of the Pre-Raphaelites, he forged a distinctive style characterized by clarity, realism, and psychological insight. As one of the foremost portrait painters of his day, he captured the likenesses of a generation of prominent Britons, leaving behind an invaluable historical record. His narrative paintings, exploring themes from history, mythology, and contemporary life, further demonstrate his skill as a storyteller and his engagement with the cultural concerns of his time. Through his paintings and his writings on technique, Collier solidified his place as a significant artist and an articulate proponent of representational painting, whose legacy continues to be appreciated for its craftsmanship and enduring appeal.