John Robert Cozens stands as a pivotal figure in the evolution of British landscape painting, particularly within the medium of watercolour. Active during the latter half of the eighteenth century, Cozens bridged the gap between the topographical traditions of earlier artists and the burgeoning Romantic movement. His evocative, atmospheric depictions of the European landscape, especially the Alps and Italy, captured a sense of poetry, mystery, and sublime grandeur that profoundly influenced subsequent generations, most notably J.M.W. Turner and Thomas Girtin. Though his life was tragically cut short, his unique vision secured his place as one of the most original and sensitive landscape artists Britain has produced.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

John Robert Cozens was born in London in 1752. Artistry was in his blood; he was the son of the respected drawing master and watercolourist Alexander Cozens. The elder Cozens, himself an intriguing figure born in Russia, was known for his innovative teaching methods, including the famous 'blot' technique, designed to stimulate the imagination in composing landscapes. It was under his father's tutelage that John Robert received his initial artistic training, absorbing not only technical skills but likely also an inclination towards imaginative and expressive landscape interpretation.

Evidence of young Cozens' precocious talent emerged early. Some accounts suggest he produced accomplished watercolours by the age of nine. His public career began modestly but respectably; he first exhibited his works with the Incorporated Society of Artists in London in 1767, when he was just fifteen. These early works already hinted at a sensitivity to atmosphere and landscape mood that would become the hallmark of his mature style, setting him apart from purely descriptive topographical artists like Paul Sandby, who was a dominant figure at the time.

His father's influence extended beyond technical instruction. Alexander Cozens' own landscape theories, emphasizing structure and imaginative composition, likely provided a foundation upon which John Robert built his more emotionally resonant and atmospheric approach. This familial artistic environment fostered a deep engagement with the possibilities of landscape art, steering him away from mere imitation towards interpretation and poetic feeling.

The Grand Tours: Journeys of Discovery

Travel was fundamental to the development of John Robert Cozens' art. Like many artists and gentlemen of his era, he undertook journeys to the Continent, seeking inspiration and subject matter. His two major tours, particularly through the Alps and Italy, provided the raw material for the works upon which his reputation rests. These were not simply sightseeing trips; they were profound encounters with landscapes that resonated deeply with the developing Romantic sensibility.

First Journey: Switzerland and Italy with Richard Payne Knight

Between 1776 and 1779, Cozens embarked on his first significant European tour. He travelled through Switzerland and into Italy, acting as a draughtsman for Richard Payne Knight. Knight was a prominent connoisseur, collector, and theorist, known for his writings on aesthetics, particularly the concept of the Picturesque. Travelling with such a figure undoubtedly exposed Cozens to contemporary ideas about landscape appreciation and representation.

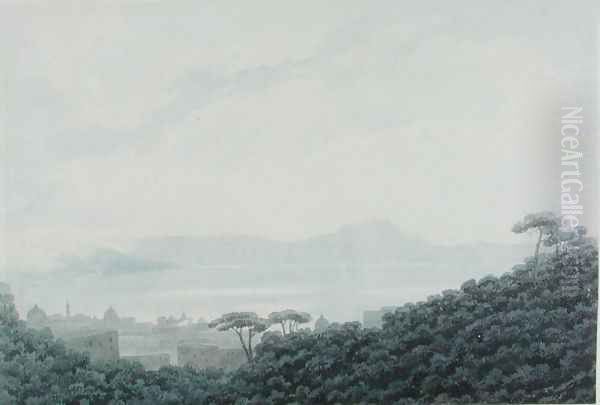

This journey was immensely productive. Cozens created numerous sketches and finished watercolours documenting the dramatic scenery of the Alps and the classical landscapes of Italy, including Rome and its environs. A series of fifty-four watercolours resulting from this trip, commissioned by Knight, showcases his burgeoning mastery of atmospheric effects. Works like Lake Albano (1777) exemplify his ability to capture the serene, slightly melancholic beauty of the Italian lakes, using subtle tonal gradations and a limited palette to evoke mood rather than precise detail. The sublime power of the Alps also left an indelible mark, visible in his depictions of vast mountain ranges shrouded in mist.

Second Journey: Italy with William Beckford

A second major tour took place between 1782 and 1783, this time in the company of the wealthy, eccentric, and controversial figure William Beckford. Beckford, famous as the author of the Gothic novel Vathek and the builder of the fantastical Fonthill Abbey, was another significant patron. Cozens accompanied Beckford through Italy, spending considerable time in Naples and its surroundings.

This later Italian journey seems to have further deepened the poetic and sometimes melancholic quality of Cozens' work. The sketches and subsequent watercolours from this period often possess an even greater sense of atmosphere and emotional depth. Subjects included coastal views, ancient ruins, and the distinctive landscapes of southern Italy. Works derived from this period, such as A Cavern in the Campagna (likely based on sketches from his travels, though dated 1786), demonstrate his fascination with dramatic natural formations and the interplay of light and shadow, often imbued with a sense of mystery and timelessness. Views like A Castle on a Hilltop near Naples capture the picturesque qualities of the Italian scene, filtered through his unique sensibility.

Artistic Style: Atmosphere, Mood, and Sublimity

John Robert Cozens forged a distinctive artistic style that set him apart from his contemporaries and anticipated key elements of Romanticism. His primary medium was watercolour, which he handled with extraordinary subtlety and control, prioritizing tone and atmosphere over bright colour and intricate detail.

His technique involved building up landscapes through delicate, overlapping washes of predominantly cool colours – blues, greys, greens, and muted browns. This allowed him to achieve remarkable effects of aerial perspective, suggesting vast distances and the veiling effects of mist, haze, or twilight. Unlike the clear, bright linearity often found in earlier topographical watercolours, Cozens' forms are often softened, their edges blurred, merging into the surrounding atmosphere. This focus on tone and light created a powerful sense of unity and mood within his compositions.

The subjects Cozens favoured were landscapes imbued with historical resonance or natural grandeur: the towering peaks of the Alps, the serene expanses of Italian lakes like Nemi and Albano, the ancient ruins scattered across the Roman Campagna, and secluded villas like the Villa Lante on the Janiculum, Rome. However, his aim was never simply to record these scenes accurately. Instead, he sought to capture their emotional essence, their poetic spirit. His works often evoke feelings of melancholy, serenity, awe, or gentle contemplation.

Cozens' art resonates strongly with the aesthetic concepts of the Sublime and the Picturesque, which were gaining currency in the late eighteenth century. The Sublime, associated with feelings of awe, vastness, and even terror experienced before powerful natural phenomena (like the Alps), is palpable in many of his mountain scenes. The Picturesque, related to the appreciation of varied, irregular, and textured landscapes often featuring ruins or rustic elements (like the Italian countryside), also informs his compositions. Yet, Cozens transcends formulaic application of these ideas, infusing his work with a deeply personal, almost dreamlike quality. John Constable famously remarked that Cozens was "all poetry," highlighting this essential characteristic of his art.

Influence and Legacy: Shaping British Landscape Painting

Despite his relatively short career and the specialized nature of his watercolour practice, John Robert Cozens exerted a profound influence on the course of British landscape art. His work served as a crucial link between the classical landscape tradition, represented by artists like Richard Wilson, and the full flowering of Romanticism in the early nineteenth century. His impact was felt most strongly by the next generation of watercolour masters, particularly Thomas Girtin and J.M.W. Turner.

Both Girtin and Turner encountered Cozens' work at a formative stage in their careers. After Cozens suffered his mental breakdown, many of his sketches and watercolours came into the possession of Dr. Thomas Monro, the physician who cared for him. Dr. Monro was also an avid collector and patron of young artists. He established what became known as the "Monro Academy," an informal evening gathering at his home where promising young painters, including Girtin and Turner, were employed to copy works from his collection, notably those by Cozens.

This direct engagement with Cozens' art was transformative for both artists. Thomas Girtin absorbed Cozens' feeling for broad, atmospheric effects and poetic composition, developing his own powerful style characterized by rich tones and simplified forms. Girtin built upon Cozens' foundation, expanding the scale and expressive range of watercolour. His early death was lamented by Turner, who famously remarked, "Had Tom Girtin lived, I should have starved."

J.M.W. Turner's debt to Cozens was perhaps even more profound and long-lasting. Studying Cozens' Alpine scenes and Italian views helped Turner understand how to convey space, light, and atmosphere. Cozens' emphasis on mood and emotional response to landscape, rather than mere topography, resonated deeply with Turner's own developing vision. Turner himself acknowledged Cozens' importance, particularly regarding the depiction of mountain scenery, which became a major theme in his own work. While Turner would ultimately push watercolour and oil painting into radically new territories, the poetic sensibility and atmospheric depth found in Cozens remained a touchstone.

The admiration for Cozens extended to other major figures. John Constable, a key figure in British Romantic landscape painting alongside Turner, held Cozens in the highest esteem, calling him "the greatest genius that ever touched landscape." Constable recognized the unique quality of Cozens' art, its ability to transcend mere description and achieve a form of abstract, emotional beauty. This praise from an artist with such a different approach (Constable focused on the empirical study of English nature) underscores the universal appeal of Cozens' poetic vision.

His influence can also be seen in the context of other contemporary landscape artists exploring mood and atmosphere, such as Francis Towne, known for his starkly beautiful Alpine watercolours. Cozens' patrons, including Richard Payne Knight, William Beckford, and Sir George Beaumont (another highly influential collector and amateur artist), also played a role in disseminating his work and ensuring its visibility within elite artistic circles. Through these channels – direct study by younger artists, the admiration of peers, and the support of key patrons – Cozens' quiet, poetic art left an indelible mark. His father, Alexander Cozens, provided the initial training, but John Robert forged a path that significantly altered the landscape of British art. Even later artists, like John Sell Cotman, working within the watercolour tradition, operated in an artistic environment shaped in part by Cozens' innovations.

Later Years and Mental Decline

The promising career of John Robert Cozens came to a tragic and premature end. In 1793, at the height of his powers, he succumbed to a severe mental illness, described at the time as a "nervous breakdown" or "mental derangement." The exact nature of his condition is unknown, but it rendered him incapable of working.

He was placed under the care of Dr. Thomas Monro, a physician specializing in mental illness who was also, as mentioned, a passionate art collector and patron. Cozens spent the last few years of his life under Dr. Monro's supervision. While this period marked the end of his creative output, it paradoxically became a period when his influence intensified, as Monro made Cozens' works available for study by the young Turner, Girtin, and others in his informal 'academy'.

John Robert Cozens died in London in December 1797, at the relatively young age of 45. His death silenced a unique artistic voice, but the body of work he had already created was substantial enough to secure his legacy. The circumstances of his final years add a layer of poignancy to the often melancholic and ethereal beauty of his landscapes.

Art Historical Evaluation

In the annals of British art history, John Robert Cozens occupies a unique and significant position. He is widely regarded as one of the most original landscape painters of the eighteenth century and a crucial forerunner of the Romantic movement in Britain. His primary contribution lies in his transformation of watercolour from a predominantly topographical medium into one capable of profound poetic expression and atmospheric subtlety.

His focus on mood, feeling, and the evocative power of light and atmosphere, rather than precise detail, marked a decisive shift towards a more subjective interpretation of nature. His depictions of the Alps and the Italian landscape, particularly works like Lake Albano, Villa Lante on the Janiculum, Rome, and A Cavern in the Campagna, are celebrated for their delicate tonal harmonies, their sense of mystery, and their serene, often melancholic, beauty. He captured the sublime grandeur of mountains and the poetic resonance of classical lands with unparalleled sensitivity.

While sometimes described as having a limited range or a 'primitive' technique compared to the dazzling virtuosity of later artists like Turner, this assessment misses the point of his unique genius. His strength lay precisely in his restraint, his mastery of suggestion, and his ability to distill the essence of a landscape's mood. As Constable perceived, his work transcended mere representation to become "poetry."

His influence on Turner and Girtin alone would be enough to guarantee his importance, acting as a vital catalyst for the golden age of English watercolour painting. He demonstrated the potential of the medium for serious artistic expression, paving the way for its elevation in status during the early nineteenth century. Today, his works are held in major collections worldwide, including Tate Britain, the British Museum, and the Victoria and Albert Museum, and continue to be admired for their quiet intensity and enduring atmospheric power.

Conclusion

John Robert Cozens remains a figure of profound importance in British art. Working primarily in the subtle medium of watercolour, he developed a deeply personal and poetic vision of landscape. Through his evocative depictions of Switzerland and Italy, he captured the spirit of place, emphasizing mood, atmosphere, and the emotional resonance of nature over literal description. His innovations in technique and his romantic sensibility had a decisive impact on the succeeding generation, most notably Turner and Girtin, helping to shape the future of landscape painting in Britain. Though his life ended prematurely under tragic circumstances, the haunting beauty and quiet intensity of his work ensure his legacy as a master of atmospheric landscape and a true poet in watercolour.