Francis Towne stands as a unique figure in the history of British art. Active during the latter half of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, he dedicated his career primarily to the medium of watercolour, developing a style that was remarkably individualistic and, in many ways, ahead of its time. Though he achieved moderate success as a drawing master, particularly in the provinces, his distinctive artistic vision received limited recognition from the London art establishment during his lifetime. It was only in the twentieth century that his true significance was appreciated, revealing him as one of the most innovative landscape watercolourists of his era.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Francis Towne was born in England around 1739 or 1740. Sources often point to Middlesex, an area now largely incorporated into London, or specifically Islington, as his place of birth. His early life remains somewhat obscure, but his path towards an artistic career became clearer when he enrolled at Shipley's School in London. This drawing school, located in the Strand, was a significant training ground for young artists during the period. Towne studied there between approximately 1755 and 1762, acquiring foundational skills in drawing and likely gaining exposure to the prevailing artistic trends of the mid-eighteenth century.

During his formative years, Towne also benefited from the guidance of Thomas Brooks, described as a coach painter. While the specifics of this mentorship are not fully detailed, Brooks likely provided practical instruction that complemented the more formal training Towne received at Shipley's. This combination of formal schooling and practical apprenticeship helped shape Towne's early artistic development, preparing him for a career focused on visual representation, particularly landscape.

A Career Based in Exeter

After completing his training in London, Towne did not remain in the capital to pursue fame within its competitive art circles. Instead, he established himself primarily in the city of Exeter, in Devon. For much of his adult life, Exeter served as his base. Here, he built a successful career as a drawing master, teaching watercolour techniques to local gentry and aspiring artists. This profession provided him with a stable income and allowed him the freedom to develop his personal artistic style.

While based in Exeter, Towne maintained connections with the London art world. He regularly sent works for exhibition in the capital, hoping to gain wider recognition. However, despite these efforts, he failed to achieve significant acclaim or membership in prestigious institutions like the Royal Academy of Arts. His style, perhaps too unconventional for contemporary tastes, did not resonate strongly with the London critics and collectors of the day. His professional life was thus characterized by provincial success as a teacher juxtaposed with limited metropolitan fame as an exhibiting artist.

Journeys of Artistic Discovery: Wales

Travel played a crucial role in shaping Francis Towne's artistic vision. Seeking fresh subjects and dramatic landscapes, he undertook several significant journeys. One of the earliest and most formative was a tour of North Wales in 1777. He made this trip in the company of James White, who was both a pupil and a relation (sometimes described as a nephew, sometimes a cousin). The rugged mountains, deep valleys, and cascading waterfalls of Wales provided Towne with powerful motifs that suited his developing style.

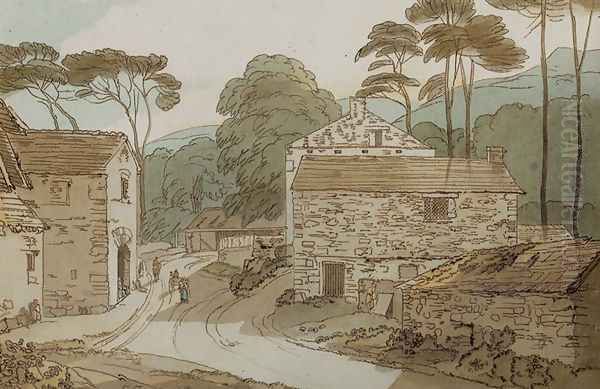

The works resulting from this Welsh tour demonstrate a growing confidence and originality. He began to refine his characteristic technique, using strong pencil outlines filled with broad, flat washes of colour. The landscapes themselves encouraged a simplification of form and an emphasis on structure, elements that would become hallmarks of his mature work. Compositions like A View of the Salmon Leap, capturing a dramatic Welsh gorge, exemplify his ability to convey the grandeur and underlying geometry of the natural world through his distinctive watercolour method during this period.

Journeys of Artistic Discovery: Italy and the Alps

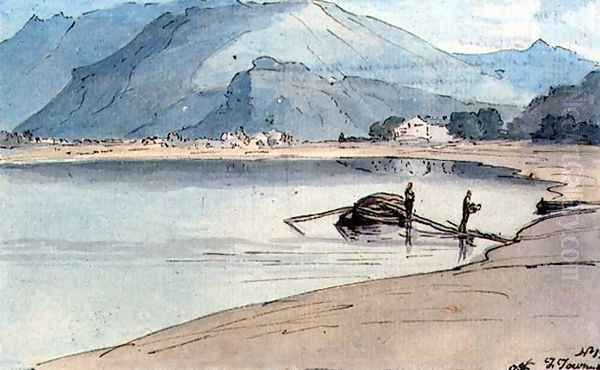

The most significant journey for Towne's artistic development was undoubtedly his trip to Italy and the Alps between 1780 and 1781. This extended tour, a version of the 'Grand Tour' popular among British artists and gentlemen, exposed him to the classical ruins of Rome and the sublime mountain scenery of the Alps. He travelled for part of this journey with fellow British landscape artists, including Thomas Jones and William Pars. John Warwick Smith is also mentioned as a contemporary landscape painter active during this period of European travel.

In Rome, Towne produced a remarkable series of watercolours depicting the city's ancient monuments and surrounding Campagna. He was captivated by the strong Mediterranean light and the clear architectural forms of structures like the Colosseum and the Baths of Caracalla. His Italian works are noted for their clarity, their precise observation of light and shadow, and their emphasis on geometric composition. Works such as The Gardens of Villa Mellini showcase his sensitivity to light effects and architectural settings.

The return journey through the Alps provided equally powerful inspiration. Towne was profoundly struck by the scale and structure of the mountains and glaciers. William Pars had already exhibited Alpine scenes in London, indicating a growing interest in such dramatic subjects. Towne's own Alpine watercolours are among his most striking, reducing the complex mountain forms to bold, interlocking shapes defined by clean lines and subtle tonal washes. This experience solidified his unique approach to landscape representation. Some sources also mention a later, perhaps independent, trip to Rome around 1807, suggesting a lifelong fascination with the city, though the 1780-81 visit remains central to his artistic evolution.

The Distinctive Towne Style: Geometry, Light, and Wash

Francis Towne's artistic style is highly distinctive and instantly recognizable. He developed a technique that departed significantly from the more detailed, picturesque conventions favoured by many of his contemporaries. His method typically involved creating a precise, often delicate, pencil drawing directly onto the paper, outlining the main forms of the landscape. He would then apply washes of watercolour, often in broad, flat areas, respecting the boundaries set by the pencil lines.

This technique emphasized structure and pattern over intricate detail. Towne often used a limited palette, favouring subtle greens, blues, greys, and browns, applied with remarkable control. His handling of light was crucial; he used tonal contrasts to define form and create a sense of atmosphere, often capturing specific times of day or weather conditions with great clarity. The overall effect is one of order, clarity, and geometric simplification. His compositions feel carefully constructed, almost abstract in their reduction of natural forms to their essential shapes.

This approach resulted in works that possess a cool, restrained, and somewhat unemotional beauty. There is a sense of detachment, a focus on the formal qualities of the landscape rather than overt romantic sentiment. This very quality, which perhaps limited his appeal in the eighteenth century, is what makes his work seem so remarkably modern to later viewers. His emphasis on flat planes of colour and strong linear design anticipates trends that would emerge much later in the history of art.

Representative Works and Landscape Themes

Several key works exemplify Francis Towne's unique artistic vision and his preferred landscape subjects. His watercolours from the Alps, such as Ambleside (though titled after an English Lake District location, it often represents his Alpine style), are considered masterpieces of mountain painting. These works capture the immense scale and geological structure of the peaks with an almost architectural clarity, showcasing his ability to simplify complex forms into powerful, near-abstract designs. He is rightly regarded as one of the great interpreters of mountain scenery in the eighteenth century.

His depictions of Devon, his home county for many years, also form an important part of his oeuvre. Lake Windermere (potentially misattributed regarding location in the source snippets, as Windermere is in the Lake District, but likely representing his English landscape style) and Waterfall at Chudleigh Rock demonstrate his ability to apply his distinctive style to the gentler, though still dramatic, scenery of South West England. These works often feature carefully rendered trees, flowing water, and rocky outcrops, all treated with his characteristic precision and control of wash.

His Italian views, particularly those of Rome like The Gardens of Villa Mellini, highlight his fascination with classical architecture and the effects of strong sunlight. Across all these locations – Wales, Italy, the Alps, and Devon – Towne consistently applied his unique stylistic principles, focusing on structure, light, and the simplification of form through line and wash.

Artistic Circle, Influences, and Context

While Towne operated somewhat outside the mainstream London art world, he was not entirely isolated. His early training connected him with Thomas Brooks and the environment of Shipley's School. He maintained relationships with pupils like John White (also a relation) and John Warren. His travels brought him into contact with contemporaries like Thomas Jones, William Pars, and potentially John Warwick Smith, sharing experiences and perhaps exchanging ideas, particularly regarding the depiction of Italian and Alpine scenery.

His legacy was passed down through his family, notably via his relation James White (possibly the same person as John White, or a separate nephew figure), who inherited many works, and subsequently through James's heir, John Herman Merivale. These individuals played a crucial role in preserving Towne's artistic output for future generations.

In terms of broader artistic context, Towne's work can be seen in relation to pioneers of British landscape painting and watercolour, such as Paul Sandby and Richard Wilson. While stylistically different, these artists helped establish landscape as a serious genre in Britain and popularized watercolour as a medium. Some commentators have noted a potential affinity between Towne's dramatic landscapes and the sublime works of the seventeenth-century painter Salvatore Rosa, whose wild Italian scenes were influential throughout the eighteenth century, suggesting Towne may have drawn inspiration from his precursor's powerful compositions.

Later Life, Obscurity, and Rediscovery

After his travels, Francis Towne returned to England and continued his career, primarily based in Exeter and later possibly moving back to London or Islington towards the end of his life. He continued to teach and paint, producing a large body of work. Despite his dedication and unique talent, he remained largely unrecognized by the official art institutions. He never became a member of the Royal Academy, a significant marker of success for artists of his time. He lived a relatively quiet, perhaps even secluded, life, unmarried, and focused on his art.

Francis Towne died in 1816, at the age of approximately 77. For nearly a century after his death, his work remained largely forgotten by the wider art world, preserved mainly through his family heirs. The turning point came in the early twentieth century, particularly around the 1930s, when critics and art historians, notably A. P. Oppé (though not mentioned in the source snippets, his role was pivotal), began to re-evaluate Towne's watercolours. They recognized the extraordinary originality and modernity of his style.

This rediscovery led to a dramatic reassessment of his place in British art history. Far from being a minor provincial drawing master, Towne came to be seen as a highly innovative artist whose work possessed a unique aesthetic sensibility. His geometric simplification and bold use of flat washes resonated with modern artistic tastes, leading some to draw comparisons with twentieth-century artists like John Nash, who shared an interest in structured landscape design.

Enduring Significance and Legacy

Today, Francis Towne is highly regarded as a major figure in the development of British watercolour painting. His posthumous reputation far exceeds the recognition he received during his lifetime. His large body of work, meticulously documented in a comprehensive catalogue raisonné listing over a thousand pieces, attests to his prolific output and consistent vision. Major museums, including the British Museum, the Tate Britain, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, hold significant collections of his watercolours, making his art accessible to the public.

His influence lies not in having founded a school or having had numerous direct followers, but in the singular quality of his artistic vision. He demonstrated a way of seeing and representing the landscape that was profoundly personal and forward-looking. His emphasis on pattern, structure, and the abstract qualities of natural forms, combined with his mastery of the watercolour medium, marks him as an artist of exceptional originality.

Francis Towne's story is a compelling example of how artistic merit can sometimes be overlooked by contemporary audiences, only to be fully appreciated by later generations. His journey from provincial obscurity to posthumous acclaim underscores the importance of rediscovering artists who deviated from the prevailing norms of their time. He remains a testament to the power of individual style and a key figure for understanding the rich diversity of British landscape art in the eighteenth century. His cool, elegant, and structurally profound watercolours continue to captivate viewers with their unique beauty.