Joseph Benoit Suvée (1743-1807) stands as a significant, if sometimes overshadowed, figure in the landscape of late 18th and early 19th-century European art. A Flemish painter by birth, he navigated the shifting artistic currents from the waning Rococo to the ascendant Neoclassical style, leaving an indelible mark both as a creator and an educator. His career, marked by prestigious accolades, intense rivalries, and the socio-political upheavals of his time, offers a fascinating glimpse into the life of an artist dedicated to the classical ideal. From his early training in Bruges to his influential tenure as Director of the French Academy in Rome, Suvée's journey is one of artistic dedication and quiet perseverance.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Bruges

Born in Bruges, a city with a rich artistic heritage stretching back to the Flemish Primitives like Jan van Eyck and Hans Memling, Joseph Benoit Suvée was immersed in a culture that valued artistic skill from a young age. In 1743, the year of his birth, Bruges, though past its medieval commercial zenith, still maintained a respectable artistic environment. He demonstrated precocious talent, reportedly beginning his formal artistic studies at the tender age of eight at the Bruges Royal Academy of Fine Arts (Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten). This institution, like many others across Europe, was dedicated to upholding academic principles of art, emphasizing drawing from casts and life models.

Suvée excelled in this environment. By 1761, at just eighteen, he had already distinguished himself by winning first prize in both painting and architecture at the Bruges Academy. This early success was a clear indicator of his burgeoning talent and his ambition. The dual focus on painting and architecture in his early training would subtly inform his later compositions, often characterized by a strong sense of structure and spatial clarity, hallmarks of the Neoclassical aesthetic he would come to embrace. His foundational years in Bruges provided him with the technical skills and the drive to seek further advancement in a larger artistic center.

Parisian Aspirations and Academic Ascent

The allure of Paris, then the undisputed epicenter of the European art world, was irresistible for an ambitious young artist like Suvée. Around 1763, he made the pivotal move to the French capital. There, he sought out the tutelage of Jean-Jacques Bachelier (1724-1806), a painter and director of the Sèvres porcelain manufactory, known for his flower paintings but also a respected academic figure. Bachelier was an influential teacher who had himself been a student of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, and he ran a free drawing school, emphasizing rigorous training. Under Bachelier, Suvée would have further honed his skills, preparing for the demanding environment of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture.

Suvée was admitted as a student to the prestigious Académie Royale, the gateway to official recognition and patronage in France. The Academy, founded in the 17th century, dictated artistic taste and provided a structured path for aspiring artists, culminating in the coveted Prix de Rome. This prize, a scholarship for several years of study at the French Academy in Rome, was the ultimate goal for history painters, the most esteemed genre in the academic hierarchy. Suvée diligently worked towards this, absorbing the prevailing artistic theories and refining his technique in a city that was becoming a crucible for a new, more austere artistic style reacting against the perceived frivolity of Rococo, championed by artists like François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

The Prix de Rome and the Roman Sojourn

The year 1771 was a watershed moment in Suvée's career. He entered the fiercely competitive Prix de Rome competition. The set subject for that year was "The Combat of Mars and Minerva." His principal rival was a young, fiercely ambitious painter named Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), who would later become the leading figure of French Neoclassicism and a dominant force in European art. To the surprise and considerable chagrin of David, Suvée was awarded the first prize. This victory was a significant achievement, securing his passage to Rome and placing him in the top echelon of young French (or, in his case, French-affiliated Flemish) talent. David, who felt the prize was rightfully his, developed a lasting animosity towards Suvée, a rivalry that would simmer throughout their careers.

From 1772 to 1778, Suvée resided in Rome as a pensionnaire of the French Academy, then under the directorship of painters like Charles-Joseph Natoire and later Joseph-Marie Vien (David's own teacher, who arrived in Rome as director in 1775). Rome was a transformative experience. He immersed himself in the study of classical antiquity – the ruins, sculptures, and architectural marvels that were the wellspring of Neoclassical inspiration. He also diligently studied the works of Renaissance masters like Raphael and Michelangelo, and Bolognese classicists such as Annibale Carracci and Domenichino. Beyond his official history paintings, Suvée produced numerous red chalk drawings of Roman landscapes and ancient monuments. These drawings, often imbued with a poetic sensibility, combined archaeological accuracy with a grand, sometimes picturesque, vision, reflecting the era's burgeoning interest in both scientific observation and romantic sentiment. His contemporaries in Rome included other aspiring artists, and the environment was one of intense study and artistic exchange, though undoubtedly colored by the existing tensions, particularly with David who arrived in Rome in 1775, having won the Prix de Rome in 1774.

Return to Paris: Academician and Educator

Upon his return to Paris in 1778, Suvée sought to capitalize on his Roman experience and establish his career. He was quickly approved (agréé) by the Académie Royale in 1779 and presented his reception piece, The Birth of the Virgin, to become a full member (académicien) in 1780. This status granted him the right to exhibit regularly at the prestigious Paris Salon, the official art exhibition that could make or break an artist's reputation. Suvée became a respected, if not always headline-grabbing, figure in the Parisian art scene.

A notable aspect of Suvée's Parisian career was his commitment to teaching. He established a drawing school specifically for young women, located within the Louvre itself. This was a progressive step in an era when opportunities for formal artistic training for women were severely limited. Figures like Adélaïde Labille-Guiard and Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun were exceptional talents who navigated the male-dominated art world, and Suvée's initiative provided a structured environment for other aspiring female artists. This dedication to pedagogy would remain a constant throughout his life, shaping many young talents. His own style, a refined and somewhat gentle form of Neoclassicism, continued to develop, often focusing on historical and religious subjects rendered with clarity, balanced composition, and a smooth finish.

Masterworks and Artistic Style: Defining Suvée's Neoclassicism

Suvée's artistic output, while perhaps not as voluminous or revolutionary as that of his rival David, includes several key works that exemplify his Neoclassical approach. His style, while firmly rooted in the principles of order, clarity, and moral seriousness advocated by theorists like Johann Joachim Winckelmann, often retained a certain grace and sensitivity that distinguished it from the more severe and heroic classicism of David.

_The Combat of Mars and Minerva_ (1771): This was the painting that secured Suvée the Prix de Rome. Now housed in the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lille, the work depicts the mythological clash between the god of war and the goddess of wisdom and strategic warfare. The composition is dynamic yet ordered, with figures rendered in a classical idiom. Minerva, representing reason and controlled strength, triumphs over the brute force of Mars. The painting demonstrates Suvée's mastery of anatomy, complex figural arrangement, and the academic conventions of history painting. Its success highlighted his ability to interpret a classical theme with vigor and technical proficiency, meeting the Academy's expectations.

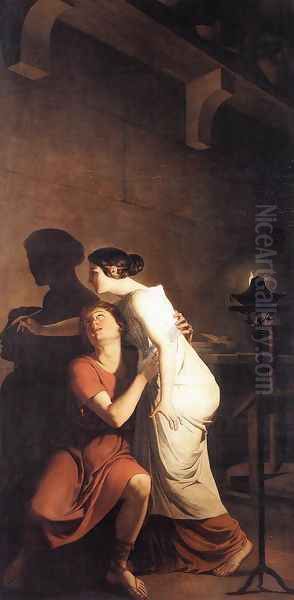

_The Invention of the Art of Drawing_ (also known as _Dibutades Tracing the Portrait of Her Shepherd Lover_) (1791): Perhaps Suvée's most famous work, this painting, now in the Groeningemuseum in Bruges, is a quintessential example of sentimental Neoclassicism. It illustrates the legendary origin of drawing as recounted by Pliny the Elder: Kora of Sicyon (often called Dibutades, after her father, a potter) traces the shadow of her departing lover on a wall, seeking to preserve his image. The scene is intimate and tender, illuminated by lamplight that creates dramatic chiaroscuro. The figures are idealized, their poses graceful, and the emotion is palpable yet restrained. The painting not only celebrates the origins of art but also touches upon themes of love, memory, and the power of representation. It resonated with contemporary sensibilities and showcased Suvée's ability to imbue classical forms with relatable human feeling. This work is often compared to a similar subject painted by Jean-Baptiste Regnault around the same time.

Suvée's Neoclassicism was characterized by meticulous draughtsmanship, balanced compositions, often employing a frieze-like arrangement of figures, and a palette that, while clear, could be richer and more nuanced than the starker colors sometimes favored by David. He explored themes from mythology, ancient history, and the Bible, always aiming for a sense of decorum and elevated sentiment. His work can be seen as a bridge between the lingering elegance of the French classical tradition and the more rigorous demands of the burgeoning Neoclassical movement, influenced by archaeological discoveries at Pompeii and Herculaneum and the writings of scholars like Winckelmann and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing.

Navigating the French Revolution and Its Aftermath

The French Revolution, beginning in 1789, profoundly reshaped French society and its artistic institutions. The Académie Royale was abolished in 1793, a move championed by Jacques-Louis David, who had become a fervent revolutionary and a powerful figure in the new Republic's cultural politics. For artists like Suvée, who were associated with the Ancien Régime's structures, this was a period of uncertainty and, in some cases, peril.

Despite the turmoil, Suvée's reputation endured. In 1792, he was appointed Director of the French Academy in Rome. However, the escalating revolutionary fervor and the political instability in both France and Italy prevented him from taking up this prestigious post immediately. Indeed, his career took a dramatic and dangerous turn. Due to political machinations, possibly fueled by his old rival David who had become the virtual "art dictator" of France, Suvée found himself imprisoned in the Saint-Lazare prison in Paris for a period. This notorious prison held many perceived enemies of the Revolution, and it was a harrowing experience.

It was not until 1801, under the more stable conditions of Napoleon Bonaparte's Consulate, that Suvée was finally able to travel to Rome and assume his duties as Director of the French Academy, which had been re-established at the Villa Medici. This appointment was a testament to his recognized abilities as an artist and administrator. As Director, he was responsible for overseeing the studies of a new generation of French artists who had won the Prix de Rome, guiding their artistic development and ensuring they made the most of their time in the Eternal City.

Directorship in Rome and Final Years

Suvée's tenure as Director of the French Academy in Rome lasted from 1801 until his death in 1807. During these years, he worked to restore the Academy's prestige and provide a supportive environment for its students. Among the young artists who would have been at the Villa Medici during or shortly after his directorship was Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), who arrived in 1806 after winning the Prix de Rome in 1801 (though his departure was delayed). Suvée's own artistic production continued, though his administrative duties likely consumed much of his energy.

He was respected by the students for his fairness and dedication. His own experiences as a pensionnaire decades earlier undoubtedly informed his approach to guiding young talents. He encouraged rigorous study of the antique and the Renaissance masters, upholding the Neoclassical principles that had defined his own career. His directorship coincided with Napoleon's consolidation of power and the expansion of French influence across Europe, and the French Academy in Rome played a role in projecting French cultural prestige. Suvée died in Rome in 1807, still serving as Director, bringing to a close a career that had spanned some of the most dynamic and transformative decades in European art history.

Pupils and Enduring Legacy

Joseph Benoit Suvée's influence extended significantly through his role as an educator. In Paris, his school for women was an important, if often overlooked, contribution. In Rome, as Director, he shaped a generation of French artists. Many Flemish artists also benefited from his guidance or were inspired by his success, looking to him as a model for achieving international recognition.

Among his notable pupils were:

André Ségla: A friend and student whose portrait Suvée painted.

Joseph Denis Odevaere (1775-1830): A fellow Bruges native who studied with Suvée and later with David, becoming a prominent Neoclassical painter in Belgium.

Jean-Baptiste Joseph Deville

Joseph Dauwe

Augustin van den Berghe (1756-1836): Also from Bruges, he studied with Suvée and later became a professor at the academy in Beauvais.

Albert Gregorius (1774-1853): Another Bruges artist who, after initial training in his hometown, studied in Paris, likely encountering Suvée's influence, and later became director of the Bruges Academy.

Beyond these individuals, Suvée's broader legacy lies in his consistent adherence to Neoclassical ideals, tempered with a Flemish sensibility for careful execution and often a more gentle emotional tone than some of his French contemporaries like David or Jean-Germain Drouais. He played a crucial role in transmitting these ideals to his students and in maintaining the standards of academic art. While David's more dramatic and politically charged Neoclassicism often dominates historical narratives, Suvée represents another facet of the movement – one characterized by sustained dedication, scholarly engagement with the classical past, and a commitment to the craft of painting. His career demonstrates the international character of Neoclassicism, with artists from across Europe, including from Flanders like himself, contributing to its development and dissemination. Other key Neoclassical figures whose careers intersected or ran parallel include Jean-François Peyron (a rival of David for the Prix de Rome), François-André Vincent (another Prix de Rome winner), Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson (a student of David), and Pierre-Paul Prud'hon, whose style offered a softer, more lyrical alternative within the broader Neoclassical framework.

Conclusion: A Measured Master of His Time

Joseph Benoit Suvée was an artist of considerable talent and unwavering dedication. From his early triumphs in Bruges to his leadership of the French Academy in Rome, he navigated the complex art world of his era with skill and integrity. His victory in the 1771 Prix de Rome over Jacques-Louis David set the stage for a career that, while perhaps less flamboyant than his rival's, was marked by consistent quality and a deep commitment to the principles of Neoclassicism. His paintings, such as The Combat of Mars and Minerva and The Invention of the Art of Drawing, remain important examples of the style, showcasing his technical mastery and his ability to convey both grand historical narratives and tender human emotions.

As an educator, Suvée's impact was significant, particularly his pioneering school for women artists in Paris and his later directorship in Rome. He helped shape a generation of artists, instilling in them the values of classical art. Though sometimes overshadowed by more revolutionary figures, Joseph Benoit Suvée holds a secure place in art history as a distinguished Flemish painter who made significant contributions to the Neoclassical movement, leaving behind a legacy of refined artistry and dedicated mentorship. His life and work offer a valuable perspective on the artistic culture of a transformative period in European history.