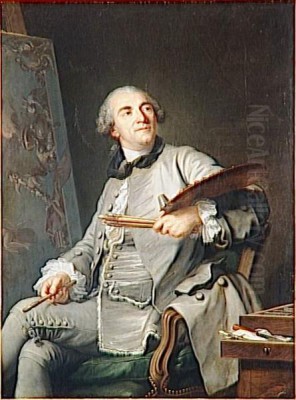

Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre stands as a significant, albeit sometimes complex, figure in the landscape of eighteenth-century French art. Born into the vibrant artistic milieu of Paris on March 6, 1714, his life spanned a period of profound stylistic transition, from the exuberant Rococo favoured during the reign of Louis XV to the burgeoning severity of Neoclassicism that would dominate the era of Louis XVI and the French Revolution. Pierre was not merely a painter; his talents extended to printmaking, drawing, and crucially, arts administration, culminating in his appointment as the most powerful artist in the kingdom: the Premier Peintre du Roi (First Painter to the King). His death on May 15, 1789, occurred just weeks before the storming of the Bastille, marking the end of an era he had both shaped and represented.

Pierre's career trajectory was emblematic of the path to success within the highly structured French academic system. He navigated its hierarchies with skill, securing prestigious commissions and ultimately wielding considerable influence over artistic production and education. While his own artistic output, particularly in history painting and large-scale decoration, earned him renown, his later years were increasingly dedicated to his official duties, leading some critics, both contemporary and modern, to view his administrative role as overshadowing his creative practice. Nonetheless, his work remains a vital testament to the artistic tastes and ambitions of France during the Ancien Régime, bridging stylistic divides and leaving an indelible mark on institutions like the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture and the Gobelins Manufactory.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre's artistic journey began in Paris, the undisputed centre of European art and culture in the early 18th century. While details of his earliest training are somewhat sparse, it is known that he studied under notable figures, likely including artists associated with the Académie Royale. The structured environment of the Parisian ateliers provided young artists like Pierre with a rigorous grounding in drawing from life, copying Old Masters, and understanding the principles of composition and perspective, essential skills for aspiring history painters.

The pivotal moment in his early career arrived in 1734. At the age of just twenty, Pierre achieved the highest honour available to a young French artist: the prestigious Prix de Rome. This prize, awarded by the Académie Royale, granted the winner a funded period of study at the French Academy in Rome. Pierre's winning entry was a history painting depicting the dramatic biblical scene Samson Handed Over to the Philistines by Delilah. Although this specific canvas is now unfortunately lost, the victory itself catapulted Pierre into the elite ranks of aspiring artists and set the stage for the next crucial phase of his development.

Winning the Prix de Rome was more than just an accolade; it was a passport to the heart of the classical world and the cradle of the Renaissance and Baroque. The prospect of studying in Rome, surrounded by the masterpieces of antiquity and the Italian masters, was considered indispensable for any artist aiming for success in the 'grand genre' of history painting, the most esteemed category within the academic hierarchy. Pierre's success demonstrated his early mastery of complex narrative composition and dramatic expression, prerequisites for tackling the historical, mythological, and religious subjects that would form the core of his oeuvre.

The Roman Sojourn: Influence and Development

Pierre's arrival at the Palazzo Mancini, home to the French Academy in Rome, marked the beginning of a formative five-year period (circa 1735-1740). Rome offered an unparalleled immersion in art history. He could study firsthand the sculptures of antiquity, the frescoes of Raphael and Michelangelo, and the powerful Baroque compositions of artists like Annibale Carracci, Domenichino, and Caravaggio. This direct exposure was fundamental to refining his technique, expanding his visual vocabulary, and deepening his understanding of the classical tradition that underpinned French academic art.

During his time in Rome, the French Academy was under the directorship of Charles-Joseph Natoire, himself a distinguished history painter whose style blended late Baroque dynamism with Rococo elegance. Natoire's influence is discernible in Pierre's work from this period and immediately following. He absorbed Natoire's fluid brushwork, his penchant for complex allegorical compositions, and his skillful handling of light and colour. This Roman training instilled in Pierre a confidence in handling large-scale formats and intricate narratives, skills essential for the decorative commissions he would later undertake.

Beyond studying the masters, Rome provided opportunities for interaction with fellow artists and patrons. It was during this time that Pierre formed a connection with Claude-Henri Watelet, a wealthy amateur artist, printmaker, and writer. Watelet, who was also in Rome, admired Pierre's talent and commissioned him to create designs, which Watelet himself then etched. This collaboration resulted in a series of prints, demonstrating Pierre's versatility and his early engagement with the medium of printmaking, often depicting pastoral or mythological scenes that resonated with the prevailing Rococo sensibility. This period solidified his technical skills and broadened his artistic network, preparing him for his return to Paris.

Return to Paris and Academic Ascent

Upon returning to Paris around 1740, Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre was well-positioned to launch his professional career. Armed with the prestige of the Prix de Rome and the invaluable experience gained in Italy, he sought recognition within the powerful Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. He submitted works to the regular Salons, the official exhibitions that were crucial for an artist's visibility and critical reception. His paintings, often featuring historical or mythological subjects executed with the technical polish and compositional sophistication honed in Rome, quickly attracted attention.

In 1742, Pierre achieved a significant milestone by being formally accepted (agréé) into the Académie Royale. Full membership (reçu) typically followed upon the submission and acceptance of a reception piece, or morceau de réception. While the specific work varies in sources, it was undoubtedly a history painting demonstrating his mastery of the grand style, likely a mythological or historical subject conforming to academic expectations. His election confirmed his status as a professional artist of standing and granted him access to royal commissions and the influential network of the Academy.

Throughout the 1740s and 1750s, Pierre solidified his reputation as one of the leading painters of his generation. He became a regular and prominent exhibitor at the Salons, showcasing major works that competed for attention alongside those of established figures like François Boucher and Carle Van Loo, and rising talents. He received numerous commissions for religious paintings for churches in Paris and the provinces, as well as decorative works for royal residences and aristocratic patrons. His style during this period often balanced the grandeur expected of history painting with a certain Rococo grace, appealing to the tastes of the time while maintaining academic decorum. He was elected a professor at the Academy in 1748, further cementing his role within the institution.

Artistic Style: Bridging Rococo and Neoclassicism

Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre's artistic style is fascinating for its position straddling two major artistic movements. He matured during the height of the Rococo, yet his career culminated as Neoclassicism gained ascendancy. His work reflects this transitional period, incorporating elements of both while forging a distinct, often imposing, personal style, particularly suited to large-scale decorative and history painting.

His grounding was firmly in the French academic tradition, which emphasized drawing, clarity of narrative, and adherence to classical principles, albeit interpreted through a Baroque lens inherited from predecessors like Charles Le Brun. From his Roman studies and the influence of Natoire, he adopted a fluid brushwork, a rich colour palette, and a dynamic sense of composition, often employing swirling diagonals and dramatic lighting effects reminiscent of the Italian Baroque. This is evident in many of his religious and mythological works, which possess an energy and theatricality characteristic of the era.

However, compared to the quintessential Rococo master François Boucher, whom he would eventually succeed as Premier Peintre, Pierre's work often exhibits greater sobriety and weight. While Boucher excelled in lighthearted, sensuous mythologies and pastorals, Pierre frequently tackled more serious themes or imbued his subjects with a grandeur and scale that leaned towards the 'grand style'. His figures often have a solidity and anatomical precision that anticipates Neoclassical concerns, even when placed within Rococo-inflected settings. Works like The Death of Harmonia (c. 1740-41, Metropolitan Museum of Art), created shortly after his return from Rome, showcase this blend: dynamic composition and rich colour combined with a serious historical subject treated with dramatic intensity.

As Neoclassicism began to emerge in the latter half of his career, championed by artists like Joseph-Marie Vien and Jacques-Louis David, Pierre's style did not fully embrace its severity, linearity, and archaeological precision. He remained largely committed to the painterly values and compositional structures he had mastered earlier. This adherence to a style perceived as less 'modern' by proponents of the Neoclassical reform perhaps contributed to the criticism he faced later in life, particularly from Enlightenment critics like Denis Diderot, who increasingly favoured Greuze's sentimentality or the nascent Neoclassical aesthetic. Pierre's style, therefore, represents a powerful, often majestic, iteration of the late Baroque and Rococo traditions, adapted for large-scale official art, rather than a full conversion to the incoming Neoclassical ideal.

Major Themes and Genres

Pierre's extensive oeuvre encompassed the primary genres favoured by the French academic system, with a clear emphasis on the most prestigious categories: history painting and large-scale religious and decorative commissions.

History Painting

This was the cornerstone of Pierre's ambition and reputation. History painting, in the academic hierarchy, included subjects drawn from the Bible, ancient history, mythology, and allegory. These works were expected to convey moral lessons, depict noble actions, and demonstrate the artist's mastery of complex compositions, human anatomy, and dramatic expression. Pierre excelled in this arena, producing numerous canvases for royal and aristocratic patrons, as well as for the Salons. His lost Prix de Rome painting, Samson and Delilah, belonged to this category, as did The Death of Harmonia. He often chose moments of high drama or emotional intensity, rendered with a dynamic composition and rich colour palette characteristic of his style.

Religious Commissions

A significant portion of Pierre's output consisted of large-scale religious paintings commissioned for churches and chapels. The 18th century saw continued patronage of religious art, and Pierre became one of the go-to artists for major projects. He created altarpieces and decorative cycles for prominent Parisian churches, including Saint-Roch, Saint-Sulpice, and potentially contributed decorations for Notre-Dame Cathedral. Notable examples include his Assumption of the Virgin (c. 1752-56, Petit Palais, Paris) and Saint Francis Meditating in Solitude (1747, Petit Palais, Paris). These works often combined intense piety with theatrical presentation, fulfilling their devotional function while showcasing Pierre's skill in handling monumental formats and complex figure groups, often employing dramatic lighting effects.

Mythological Subjects and Decorative Schemes

Mythology provided fertile ground for artists to explore allegory, sensuality, and decorative possibilities. Pierre frequently painted mythological scenes, such as Leda and the Swan (c. 1750-60, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, Rio de Janeiro) and A Bacchanale: Naked Maenads Decorating a Herm. While sometimes lighter in tone, reflecting Rococo tastes, his mythological works often retained a sense of grandeur. He was particularly adept at integrating paintings into larger decorative schemes for royal palaces like Versailles, Fontainebleau, and Choisy, as well as private residences. This included designing ceiling paintings and overdoors, where mythological or allegorical themes could be woven into the architectural setting, creating opulent and unified interiors. His work for the Duke of Orléans falls into this category.

Printmaking and Other Works

While primarily a painter, Pierre was also a skilled printmaker, primarily working in etching. His prints often reproduced his own designs or explored themes complementary to his paintings. The Flight into Egypt (1758) is a notable example of a religious subject treated in print, while La Mascarade Chinoise (1735), likely based on designs from his Roman period or shortly after, reflects the contemporary fascination with Chinoiserie. He also produced drawings, which reveal his working process and mastery of draughtsmanship, such as the study for The Massacre of the Innocents (1762, Louvre). Although less central to his fame, he occasionally engaged with genre scenes or designed objects like vases, demonstrating a breadth of talent typical of leading artists of the era.

Premier Peintre du Roi: The Pinnacle of Success

In 1770, Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre reached the apex of the French artistic establishment. Following the death of François Boucher, Pierre was appointed Premier Peintre du Roi (First Painter to the King) by Louis XV. This was the highest official artistic position in the kingdom, placing him nominally above all other painters working for the crown and giving him significant influence over royal artistic patronage and policy. The appointment recognized his long and successful career, his mastery of the grand style favoured for official art, and his proven ability to manage large-scale projects.

The role of Premier Peintre was not merely honorary. It came with substantial responsibilities, including advising the King and the Surintendant des Bâtiments du Roi (Superintendent of Royal Buildings) on artistic matters, overseeing major royal commissions, and playing a leading role in the administration of artistic institutions. Pierre's duties extended to the management of the Gobelins Tapestry Manufactory, a prestigious royal enterprise for which artists provided cartoons (full-scale painted designs). He was also deeply involved in the affairs of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture.

Concurrent with his appointment as Premier Peintre, Pierre's influence within the Académie grew. He had already served as a professor and held other administrative posts. In 1778, he was elected Director of the Académie, the institution's highest administrative office (distinct from the honorary position of Chancellor). As Director, he presided over the Academy's meetings, oversaw its teaching programs, and played a key role in organizing the Salons and upholding academic standards. Holding both the Premier Peintre position and the Directorship simultaneously made Pierre arguably the most powerful figure in the French art world during the 1770s and much of the 1780s.

Administrative Influence and Critical Reception

Pierre's tenure in high office coincided with a period of increasing debate and change within the French art world. While his administrative roles granted him immense power, they also drew criticism and placed him at the centre of stylistic conflicts. As Director of the Académie and Premier Peintre, he was seen as the guardian of the established academic tradition, a tradition increasingly challenged by Enlightenment critics and the proponents of Neoclassicism.

His administrative duties were demanding, involving the management of budgets, personnel, commissions, and the complex politics of the court and the Academy. This inevitably consumed much of his time and energy, leading to a noticeable decline in his personal artistic output, particularly in easel painting. While he continued to oversee large decorative projects and the Gobelins, his focus shifted from creation to administration. Critics like Denis Diderot, whose influential Salon reviews championed artists like Jean-Baptiste Greuze and later Jacques-Louis David, often found Pierre's work and, by extension, the official art he represented, to be lacking in genuine feeling or moral seriousness compared to the emerging trends.

Pierre's position often placed him in opposition to the burgeoning Neoclassical movement. While not entirely hostile to it – the Academy under his directorship did admit and promote Neoclassical artists – his own artistic background and administrative responsibilities aligned him more closely with the established late Baroque/Rococo grand style. He was sometimes perceived as resistant to reform and overly concerned with maintaining the privileges and hierarchies of the academic system. This perception solidified as artists like Vien and David gained prominence, advocating for a return to perceived classical purity, linearity, and didactic historical subjects.

Despite these criticisms, Pierre's administrative influence was profound. He maintained the functioning of key artistic institutions during a period of transition. He oversaw the training of a generation of artists within the Academy schools and managed the production of significant royal commissions, including tapestries and decorative paintings that adorned royal residences. His commitment to the 'grand genre' ensured the continuation of large-scale history and religious painting, even as tastes began to shift. His influence, therefore, was complex: upholding tradition while managing institutions that would eventually be transformed by the very forces he sometimes seemed to resist.

Relationships with Contemporaries

The Parisian art world of the 18th century was a relatively small, interconnected community, and Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre interacted with nearly all its leading figures, sometimes as a mentor, colleague, competitor, or administrator.

His early influence came from figures associated with the Academy, and crucially, from Charles-Joseph Natoire during his time in Rome. Natoire's elegant, painterly style left a lasting impression on Pierre's approach to composition and colour. Back in Paris, he entered a scene dominated by established masters. Carle Van Loo, another prominent history painter and influential figure at the Academy (serving as Director before Pierre), represented the established grand style.

Pierre's most significant relationship, in terms of succession, was with François Boucher. Boucher, the epitome of the Rococo style, held the position of Premier Peintre du Roi until his death in 1770. Pierre's appointment as his successor marked a symbolic shift, though Pierre's own style retained Rococo elements. While perhaps not direct rivals in the same stylistic niche (Boucher being more associated with mythology and pastoral scenes, Pierre with grander history and religious works), they were the two dominant figures of their respective generations vying for the highest official honours.

He collaborated with the printmaker and influential art theorist Charles-Nicolas Cochin the Younger on various Academy matters and potentially on print projects. Cochin was a key figure in advocating for certain reforms and commenting on artistic standards. Pierre also maintained his early connection with the amateur artist and collector Claude-Henri Watelet.

As Neoclassicism gained momentum, Pierre interacted with its leading proponents. Joseph-Marie Vien, often considered a pioneer of the Neoclassical style in France, eventually succeeded Pierre as Premier Peintre after Pierre's death. Jacques-Louis David, the radical standard-bearer of Neoclassicism, rose to prominence during Pierre's later years as Director. While Pierre's administration oversaw David's early successes (like his reception into the Academy), their artistic ideals represented opposing poles, and David would later become a fierce critic of the academic system Pierre represented.

Other notable contemporaries included Jean-Honoré Fragonard, whose exuberant Rococo works offered a contrast to Pierre's more formal style; Jean-Siméon Chardin, master of still life and quiet genre scenes, operating outside the grand historical tradition Pierre championed; Jean-Baptiste Greuze, whose sentimental and moralizing genre scenes earned Diderot's praise but held a different place than Pierre's official art; Hubert Robert, painter of picturesque ruins; and sculptors like Étienne Maurice Falconet, who also worked for royal and aristocratic patrons and were part of the same academic milieu. Pierre navigated this complex web of relationships, leveraging his position while contending with shifting tastes and rising talents.

Later Years and Legacy

The final decade and a half of Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre's life, from the mid-1770s until his death in 1789, were largely defined by his powerful administrative roles as Premier Peintre du Roi and Director of the Académie. While he remained a figure of immense institutional authority, his personal artistic production waned, and his style increasingly appeared conservative in the face of the triumphant rise of Neoclassicism under Jacques-Louis David. The critical tide, led by voices favouring the new style's perceived virtues of clarity, austerity, and civic morality, had turned against the perceived artifice and grandeur of the tradition Pierre represented.

His focus on administration, while perhaps necessary for the functioning of the royal artistic bureaucracy, cemented his image as an establishment figure, somewhat removed from the cutting edge of artistic innovation. He continued to oversee projects at the Gobelins manufactory and likely advised on decorative schemes, but major new easel paintings became rare. His authority ensured the continuation of academic practices and the dominance of history painting as the premier genre, but the energy and excitement in the art world were shifting towards David and his followers.

Pierre died on May 15, 1789, just two months before the outbreak of the French Revolution. His death marked the end of a long and distinguished career that had spanned the reigns of Louis XV and Louis XVI. He did not live to see the dramatic upheaval that would dismantle the very institutions he had led – the abolition of the Académie Royale and the transformation of French society and its artistic patronage. In a sense, his passing symbolized the end of the Ancien Régime's artistic system.

Despite the criticisms and the overshadowing effect of Neoclassicism, Pierre's legacy is significant. He was a highly accomplished painter and decorator in the grand French tradition, responsible for numerous important religious and secular commissions. His works can be found today in major museums worldwide, including the Louvre in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Prado Museum in Madrid, the Petit Palais in Paris, and the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes in Rio de Janeiro, attesting to his skill and historical importance. He stands as a key transitional figure, embodying the late flowering of the French Baroque and Rococo grand style while holding the reins of power during the emergence of Neoclassicism. His career offers invaluable insight into the workings of the French academic system, royal patronage, and the complex interplay of art and power in 18th-century France.

Conclusion: An Artist of Transition and Authority

Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre occupies a crucial, multifaceted position in the narrative of 18th-century French art. He was far more than just a painter; he was a printmaker, a designer, and ultimately, one of the most powerful arts administrators of the Ancien Régime. His long career witnessed the zenith of the Rococo and the decisive rise of Neoclassicism, and his own work reflects this pivotal moment of transition, blending the painterly dynamism inherited from the Baroque and Rococo with the seriousness of purpose demanded by the academic tradition of history painting.

His journey through the ranks of the Académie Royale, from Prix de Rome winner to Director, and his appointment as Premier Peintre du Roi, underscore his mastery of the institutional pathways to success. In these roles, he wielded considerable influence, shaping artistic education, overseeing royal commissions, and managing the prestigious Gobelins manufactory. His leadership ensured the continued prominence of the 'grand style' and the institutions that supported it, even as new aesthetic ideals gained ground.

While his dedication to administrative duties in later life may have curtailed his personal artistic output and led to criticism from proponents of newer styles, his significant body of work – particularly his large-scale religious paintings and decorative schemes – remains a testament to his considerable talent. He skillfully navigated the demands of church, state, and aristocratic patrons, creating works characterized by compositional confidence, rich colour, and often dramatic intensity. Studying Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre provides essential insights not only into the stylistic evolution of French art but also into the complex relationship between artistic creation, institutional power, and shifting cultural values in the decades leading up to the French Revolution. He remains an indispensable figure for understanding the art and administration of the French Enlightenment era.