Joseph Crawhall III (1861-1913) stands as a distinctive and highly regarded figure in British art, particularly celebrated for his evocative and technically brilliant depictions of animals and birds. An important, albeit somewhat enigmatic, member of the Glasgow School of Painters, often referred to as the "Glasgow Boys," Crawhall carved a unique niche for himself through his mastery of watercolour, his profound empathy for his subjects, and an artistic style that blended keen observation with a remarkable memory and a subtle, pervasive humour. His work, while sharing certain affinities with his contemporaries, ultimately possessed an individuality that set him apart, earning him lasting acclaim and a dedicated following among collectors and connoisseurs.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

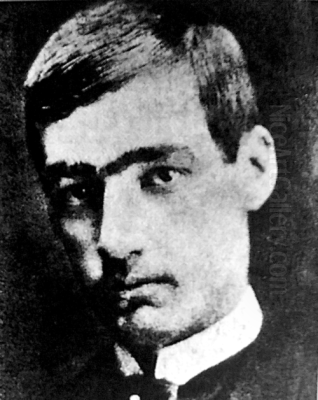

Born in Morpeth, Northumberland, on August 20, 1861, Joseph Crawhall III was immersed in an artistic environment from his earliest years. His father, Joseph Crawhall II, was himself an accomplished amateur artist, a noted antiquarian, and a significant figure in Newcastle's cultural life. The elder Crawhall was a prolific illustrator, known for his humorous and often eccentric drawings, and a passionate collector, particularly of the works of Thomas Bewick, the renowned Tyneside wood-engraver. This familial background undoubtedly nurtured young Joseph's artistic talents and instilled in him a deep appreciation for the natural world and the art of depiction.

His early artistic training was largely informal, guided by his father, who encouraged a rigorous method of drawing from memory. This practice, which involved observing a subject intently and then recreating it without direct reference, became a cornerstone of Crawhall's artistic process throughout his career. It honed his powers of observation and recall to an extraordinary degree, allowing him to capture the essence and characteristic movements of animals with uncanny accuracy and vitality. This emphasis on memory also contributed to the stylised, almost calligraphic quality that would later define his mature work, as he distilled forms to their most expressive and economical lines.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who pursued formal academic training in London or on the Continent from a young age, Crawhall's path was slightly different. His father's influence and the rich artistic milieu of Newcastle provided a strong foundation. He was also exposed to a wide range of artistic influences through his father's collections and connections, including Japanese prints, which would later play a significant role in shaping his compositional and stylistic choices.

Parisian Interlude and the Influence of Aimé Morot

In 1882, seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Joseph Crawhall travelled to Paris. There, he briefly studied under Aimé Nicolas Morot (1850-1913), a prominent French academic painter. Morot, born in Nancy, was a respected artist known for his historical scenes, portraits, and particularly his depictions of animals, especially horses and lions, often rendered with dramatic flair. He had studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris under Alexandre Cabanel and was a regular exhibitor at the Paris Salon, winning the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1873. Morot was also the son-in-law of the famous academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme.

While Crawhall's period of study with Morot was not extensive, the experience of being in Paris, then the undisputed centre of the art world, was undoubtedly formative. He would have been exposed to the ferment of artistic ideas, from the lingering influence of Realism and the Barbizon School to the burgeoning Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements. However, Crawhall's inherently individualistic temperament meant that he absorbed influences selectively, integrating them into his own developing vision rather than slavishly imitating any particular master or school. Morot's own skill in animal painting may have reinforced Crawhall's existing passion, but the direct stylistic impact of Morot on Crawhall's mature work is not overtly pronounced. Crawhall's path was already diverging towards a more personal and less conventional mode of expression.

The Glasgow School of Painters: A Confluence of Talents

Upon his return from Paris, Crawhall became increasingly associated with a group of young, rebellious artists who were transforming the Scottish art scene: the Glasgow Boys. This loose-knit group, active primarily from the late 1870s to the mid-1890s, sought to break away from the sentimental and anecdotal subject matter and the tight, detailed finish favoured by the Scottish academic establishment, particularly the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh. They championed a more modern approach, emphasizing painterly qualities, tonal harmony, and a commitment to realism, often drawing inspiration from contemporary French art, particularly the plein-air naturalism of Jules Bastien-Lepage, and the aestheticism of James McNeill Whistler.

Key figures among the Glasgow Boys included James Guthrie, E.A. Walton, John Lavery, George Henry, Arthur Melville, W.Y. Macgregor, James Paterson, E.A. Hornel, and Thomas Millie Dow. Crawhall, with his distinctive focus and technique, was a valued member of this circle. He shared their interest in capturing the truth of visual experience and their appreciation for strong design and colour. He collaborated closely with several members, notably James Guthrie and E.A. Walton. He painted with Walton at Roseneath, near Glasgow, and spent time with Guthrie at Brig o' Turk in the Trossachs and later at Crowland in Lincolnshire in 1882, before Guthrie moved to Cockburnspath in Berwickshire, which became a significant hub for the group.

The Glasgow Boys were not a homogenous group with a single manifesto; rather, they were united by a shared desire for artistic innovation and a dissatisfaction with the status quo. They often worked outdoors, directly from nature, capturing the light and atmosphere of the Scottish landscape and rural life. While Crawhall's method of working primarily from memory set him somewhat apart in terms of process, his aesthetic aims aligned with the group's broader objectives. His work was exhibited alongside theirs and contributed to the growing reputation of the Glasgow School, both nationally and internationally.

Crawhall's Unique Artistic Vision: Animals, Watercolour, and Memory

Joseph Crawhall's artistic reputation rests predominantly on his extraordinary watercolours of animals and birds. He developed a highly personal and innovative approach to the medium, often working on linen or holland cloth, which provided a textured surface that absorbed the pigment in a unique way, contributing to the distinctive quality of his work. His palette was often restrained, yet he achieved remarkable effects of colour and tone, capturing the subtle sheen of a bird's plumage or the rough texture of an animal's hide with deceptive simplicity.

His technique was characterized by its fluency and economy. Each brushstroke appears deliberate and essential, imbued with a calligraphic elegance that reflects the influence of Japanese art. This influence is also evident in his compositions, which often feature asymmetrical arrangements, flattened perspectives, and a sophisticated use of negative space. Like the Japanese masters, such as Hokusai or Hiroshige, Crawhall possessed an innate understanding of pattern and design, using these elements to enhance the expressive power of his subjects.

The cornerstone of his practice, as mentioned earlier, was his reliance on memory. He would observe his subjects intently, sometimes for extended periods, absorbing their forms, movements, and characteristic behaviours. Then, often much later, he would translate these stored impressions onto paper or linen with astonishing precision and vitality. This method allowed him to move beyond mere photographic representation, capturing the essential spirit and personality of the animal. His creatures are never sentimentalised; instead, they are depicted with a profound understanding of their nature, often imbued with a subtle, almost imperceptible humour. This humour, a defining characteristic of his work, is never forced or caricatured but arises naturally from his acute observation of animal behaviour and expression.

Masterpieces and Signature Style: Capturing the Essence

One of Crawhall's most celebrated works is "The White Drake" (c. 1895), a watercolour on linen now in the Burrell Collection, Glasgow. This striking image of a proud, assertive male duck exemplifies many of the finest qualities of his art. The composition is bold and dynamic, the bird's form rendered with a few deft, calligraphic strokes that convey both its physical presence and its inherent character. The white of the drake's plumage is set off against a subtly toned background, and the touches of colour on its beak and feet are applied with exquisite precision. The work demonstrates his mastery of design, his ability to capture movement, and his appreciation for the decorative qualities inherent in nature, likely influenced by his admiration for Chinese silk watercolours as well as Japanese prints.

Other notable works further illustrate his range and skill. "The Aviary" and "The Black Cock" showcase his ability to depict birds with both scientific accuracy and artistic flair. His equestrian subjects, often featuring horses in dynamic poses, reveal his understanding of animal anatomy and movement. In a piece like "Ware Hare," the depiction of the hare, though perhaps anatomically simplified in its alert, upright ears, conveys a palpable sense of nervous energy and wildness, tinged with his characteristic gentle humour. He had an uncanny ability to capture the individual "personality" of each creature, whether it was the haughty disdain of a camel, the sleek alertness of a greyhound, or the comical pomposity of a farmyard fowl.

His style, while sharing the Glasgow School's interest in colour and design, remained distinctly his own. Compared to the often more robust, impastoed oil paintings of some of his colleagues like Guthrie or Lavery, Crawhall's watercolours possess a refined delicacy and a graphic sensibility that set them apart. His focus on animal subjects also distinguished him, as many of the other Glasgow Boys were more concerned with landscape, portraiture, or scenes of rural labour.

Collaborations, Friendships, and Wider Connections

Beyond his core involvement with the Glasgow Boys, Crawhall maintained important artistic friendships and collaborations. His close working relationships with E.A. Walton and James Guthrie were pivotal in his early development and his integration into the Glasgow art scene. He also shared a deep appreciation for the work of Arthur Melville, another prominent member of the Glasgow Boys, whose innovative watercolour techniques and bold compositions likely resonated with Crawhall's own artistic explorations. Melville, known for his vibrant depictions of scenes from Spain, North Africa, and the Middle East, was a master of capturing light and atmosphere in watercolour, and his technical daring would have been an inspiration.

An interesting, though perhaps less direct, influence was the English artist and illustrator Charles Keene (1823-1891), known for his work for Punch magazine. Crawhall admired Keene's draughtsmanship and his ability to capture character and everyday life with wit and economy. It is documented that Crawhall himself produced over 200 illustrations for Punch, demonstrating his versatility and his engagement with the broader currents of Victorian illustration.

His connection to the legacy of Thomas Bewick, fostered by his father, remained a constant thread. Crawhall, along with J.W. Barnes, served as an executor for Isabella Bewick, Thomas Bewick's daughter. This deep-rooted appreciation for Bewick's meticulous observation and masterful wood engravings of British birds and animals undoubtedly informed Crawhall's own approach to depicting the natural world.

Crawhall was also acquainted with James McNeill Whistler, whose aesthetic theories and artistic practice had a significant impact on the Glasgow Boys. Whistler's emphasis on "art for art's sake," his interest in Japanese art, and his sophisticated use of tonal harmonies found echoes in the work of many Glasgow artists, including Crawhall.

Challenges, Evolution, and Personal Quirks

Crawhall's artistic journey was not without its challenges. His father's strict training method, which forbade the use of an eraser (India rubber), instilled a discipline that, while fostering his memory, also led to a certain perfectionism. He was known to be highly self-critical and would sometimes destroy works that he felt did not meet his exacting standards. This intense focus and the somewhat solitary nature of his memory-based process contributed to his reputation as an introverted and often silent individual, though those who knew him well also attested to his keen sense of humour and his quiet enjoyment of life's absurdities.

His artistic output was not as voluminous as that of some of his contemporaries, partly due to his meticulous process and his self-critical nature. After around 1889, his focus shifted even more decisively towards animal and bird subjects, marking a further consolidation of his unique artistic identity, perhaps moving somewhat away from the more direct stylistic influences of some of the Glasgow Boys who were heavily invested in the naturalist figure painting popularised by Bastien-Lepage.

For a time, Crawhall served as secretary of the Newcastle Arts Association. While he was keen to promote local artists, records suggest he faced challenges in attracting prominent London artists to exhibit with the association, perhaps indicating that his talents lay more in creation than in arts administration. He also experimented with other media, including woodcuts, though his primary and most successful medium remained watercolour on linen.

Later Years, Legacy, and Market Reception

Joseph Crawhall continued to produce his distinctive watercolours throughout his career, though he spent his later years in Yorkshire and then London, somewhat removed from the Glasgow art scene. He died in London on May 24, 1913, at the relatively young age of 51.

Despite his somewhat reserved nature and his specialized subject matter, Crawhall's work achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime and has continued to be highly prized. His paintings were sought after by discerning private collectors, and his reputation as one of the most original and accomplished animal painters of his generation was firmly established. He is considered one of the most important artists associated with the Glasgow School, his work adding a unique dimension to the group's collective achievement.

Today, Joseph Crawhall's works are held in major public collections, most notably the Burrell Collection in Glasgow, which houses the largest single holding of his art, comprising nearly sixty pieces. This collection showcases the full range of his talent, from mature masterpieces to experimental works and travel sketches. The Hunterian Art Gallery at the University of Glasgow also has significant holdings. Other institutions, such as the Tate Britain, the National Galleries of Scotland, and the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford (which holds manuscripts, sketches, and related documents), also possess examples of his work.

His paintings continue to perform well on the art market, admired for their technical brilliance, their aesthetic appeal, and their unique blend of observation, memory, and wit. Artists who followed, such as the Scottish painter John Maclauchlan Milne, who also specialized in animal subjects, may have looked to Crawhall's example. His influence can also be seen in the broader tradition of British animal painting, which includes figures like George Stubbs from an earlier era, and later artists who sought to capture the vitality of the animal world.

Conclusion: An Enduring Artistry

Joseph Crawhall III was an artist of singular vision and exceptional talent. Working within the dynamic context of the Glasgow School, he forged a path that was uniquely his own. His profound understanding of animal life, coupled with his innovative watercolour technique and his reliance on a powerfully trained memory, resulted in works that are both timeless and deeply personal. His ability to convey the character and spirit of his subjects with such economy of means, often tinged with a gentle humour, sets him apart. Influenced by sources as diverse as Japanese prints, the wood engravings of Thomas Bewick, and the aesthetic currents of his time, he synthesized these elements into a coherent and compelling artistic language. More than a century after his death, Joseph Crawhall's depictions of the animal kingdom continue to captivate and delight, securing his place as a master of watercolour and one of the most original figures in British art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His legacy is a testament to the power of focused observation, refined skill, and an unwavering commitment to a personal artistic truth.