Edward Atkinson Hornel stands as a significant figure in Scottish art history, a painter whose vibrant canvases captured the imagination of his contemporaries and continue to resonate today. Born far from the shores of Scotland, his life and art became intrinsically linked with the town of Kirkcudbright and the revolutionary spirit of the Glasgow Boys. His work, characterized by rich colour, decorative patterns, and an enduring fascination with childhood, nature, and distant cultures, marks him as a unique voice in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century European art.

An Unconventional Beginning: From Australia to Scotland

Edward Atkinson Hornel's story begins not in the misty glens of Scotland, but under the bright sun of Australia. He was born on July 17, 1864, in Bacchus Marsh, Victoria. His parents were Scottish immigrants, and their connection to their homeland remained strong. Seeking opportunities, they had ventured to Australia, but the pull of Scotland eventually led them back. The family returned and settled in Kirkcudbright, a picturesque harbour town in Dumfries and Galloway, when Edward was still a child. This town, with its distinctive light and artistic community, would become Hornel's lifelong home and a constant source of inspiration.

Kirkcudbright provided the backdrop for Hornel's formative years. The town's scenic beauty, its bustling harbour, and the surrounding countryside undoubtedly shaped his early visual experiences. It was here that his artistic inclinations began to surface, leading him to pursue formal training. His journey into the art world began seriously at the Trustees' Academy in Edinburgh (a precursor to the Edinburgh College of Art), where he would have received a foundational grounding in academic drawing and painting techniques.

However, like many ambitious young artists of his generation, Hornel sought broader horizons. He travelled to Antwerp, Belgium, to study at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts between 1881 and 1883. Antwerp was a significant art centre, offering exposure to both historical Flemish traditions and contemporary European trends. Studying under Charles Verlat, Hornel would have been immersed in a rigorous academic environment, yet also exposed to the burgeoning realist and plein-air movements sweeping across the continent. This period abroad was crucial, broadening his technical skills and artistic perspective beyond the confines of Scottish academicism.

The Glasgow Boys: Rebellion and Innovation

Upon returning to Scotland around 1885, Hornel did not simply rejoin the established art scene. Instead, he became associated with a dynamic and rebellious group of young painters who were challenging the conservative dominance of the Royal Scottish Academy. This loose collective became known as "The Glasgow Boys." Though centred around Glasgow, its members, including Hornel based in Kirkcudbright, shared a common goal: to paint modern life and landscape with greater realism, bolder techniques, and a fresh perspective, often drawing inspiration from French Naturalism and Impressionism.

The Glasgow Boys were not a formal school with a strict manifesto, but rather a group of friends and colleagues united by their dissatisfaction with traditional subject matter and academic polish. Key figures included James Guthrie, who became a leading figure, W.Y. Macgregor, often considered the group's father figure, John Lavery, E. A. Walton, James Paterson, and George Henry. They admired the directness and tonal realism of French painters like Jules Bastien-Lepage and the atmospheric landscapes of the Barbizon School painters such as Jean-François Millet and Camille Corot. They often worked outdoors (en plein air), capturing the specific light and atmosphere of the Scottish landscape.

Hornel quickly became an important member of this circle. His work, even in the early stages, showed an inclination towards strong colour and decorative effects that distinguished him. While sharing the group's commitment to modern subjects and techniques, Hornel's path would increasingly diverge towards a more personal, decorative, and colour-focused style. The camaraderie and shared rebellious spirit of the Glasgow Boys provided a vital context for his development, encouraging experimentation and mutual support. Their exhibitions, particularly those held in London and continental Europe from the late 1880s onwards, brought them international recognition and positioned Scottish painting at the forefront of modern European art.

A Fruitful Partnership: Hornel and George Henry

Within the Glasgow Boys, Hornel formed a particularly close artistic bond with George Henry (1858-1943). Henry, another prominent member of the group, shared Hornel's interest in colour, texture, and decorative possibilities. Their collaboration marked a significant phase in both artists' careers and produced some of the most innovative works associated with the Glasgow School. They began sharing a studio in Glasgow in 1885, fostering an environment of intense creative exchange.

Their shared interests led them to experiment boldly with technique and subject matter. They were less interested in the purely naturalistic depiction favoured by some colleagues like James Guthrie, and more drawn towards symbolism, rich surfaces, and non-naturalistic colour. This is exemplified in their most famous collaborative painting, The Druids Bringing in the Mistletoe (1890). This large, striking canvas depicts a procession of ancient Celtic figures in a snowy landscape. The painting is remarkable for its textured surface, achieved through heavy impasto and possibly incorporating materials like gesso or plaster, and its use of gold paint, lending it a ritualistic, almost Byzantine quality.

The Druids was a radical departure from conventional painting. Its emphasis on flat, decorative patterns, symbolic content, and rich, textured colour fields demonstrated a move towards Symbolism and Art Nouveau aesthetics. While critically debated at the time, the work showcased the innovative direction Hornel and Henry were exploring, pushing the boundaries of painting beyond mere representation towards evocative decoration and mood. This collaboration was pivotal, solidifying their reputations as avant-garde artists within the Glasgow movement.

The Allure of the East: The Journey to Japan

A defining moment in Hornel's artistic development was his journey to Japan with George Henry. Funded partly by the Glasgow art dealer Alexander Reid and the collector William Burrell, they embarked on this adventurous trip in 1893, staying until 1894. Japan held a powerful allure for many Western artists in the late 19th century, following the opening of the country to the West and the subsequent craze for Japonisme. Artists like James McNeill Whistler, Edgar Degas, and Vincent van Gogh had already incorporated elements of Japanese aesthetics into their work.

For Hornel and Henry, the trip was an opportunity for deep immersion. They were not merely tourists but sought to understand Japanese art and culture firsthand, particularly its principles of design, colour harmony, and spatial composition. They studied traditional Japanese woodblock prints (ukiyo-e) by masters like Hokusai and Hiroshige, admiring their flattened perspectives, bold outlines, asymmetrical compositions, and decorative use of colour. They also observed Japanese life, gardens, textiles, and crafts, absorbing the visual richness of their surroundings.

The impact of this journey on Hornel's art was profound and lasting. Upon his return, his paintings took on a distinctly brighter palette, a more pronounced emphasis on decorative pattern, and often featured Japanese subjects or motifs. Works created during and immediately after the trip depict Japanese women in kimonos, children playing, temples, and gardens. He adopted a flatter perspective and arranged figures and elements across the canvas in a manner reminiscent of Japanese prints, creating intricate, tapestry-like surfaces. This fusion of Western painting techniques with Eastern aesthetics became a hallmark of Hornel's mature style. The Japan trip solidified his reputation as a colourist and decorator, setting him apart even within the diverse Glasgow School.

Mature Style: Colour, Children, and Kirkcudbright

Following his return from Japan, Hornel settled back into life in Kirkcudbright, purchasing Broughton House in 1901, which would be his home and studio for the rest of his life. His mature style crystallized during this period, characterized by several key elements. Colour became paramount, applied in thick, mosaic-like patches (impasto) that gave his canvases a vibrant, textured surface. He often juxtaposed complementary colours to create a shimmering effect, bathing his scenes in a warm, often idealized light.

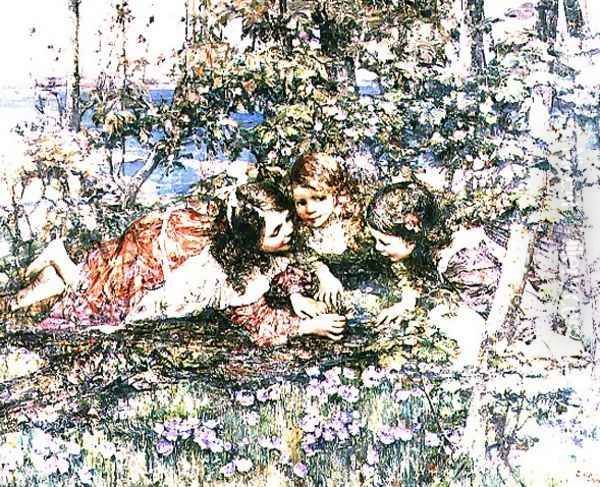

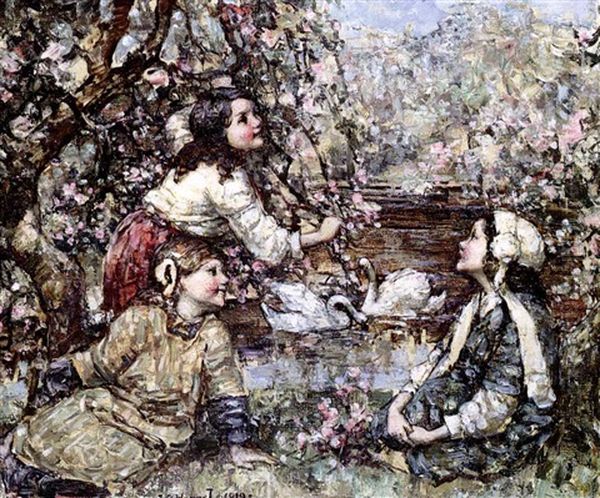

His subject matter frequently revolved around the landscapes and gardens of Kirkcudbright and Galloway, particularly the woods and shoreline near his home. Flowers became a recurring motif, rendered not with botanical precision but as vibrant masses of colour contributing to the overall decorative scheme. Perhaps his most recognizable subjects, however, were young girls, often depicted playing in idyllic natural settings, surrounded by flowers or butterflies, or paddling by the sea. Works like Summer or The Butterfly exemplify this theme.

These paintings of children, while charming, have sometimes drawn criticism for their sentimentality and repetitive nature, especially in his later career. However, they were immensely popular with the public and collectors. Hornel captured a sense of childhood innocence and harmony with nature that resonated with Edwardian sensibilities. His technique remained distinctive: figures and landscape elements were often woven together into a dense, decorative tapestry, flattening the pictorial space and emphasizing the surface pattern. This approach, blending influences from Japanese art, Post-Impressionism (particularly the work of artists like Paul Gauguin in its decorative aspect), and perhaps Celtic design, resulted in paintings that were immediately recognizable as Hornel's.

Commercial Success and Later Career

Hornel achieved considerable commercial success during his lifetime. His brightly coloured, decorative paintings of children and flowers found a ready market. He exhibited regularly in Scotland and London, and his work was acquired by collectors and public galleries. This success allowed him to live comfortably and to develop Broughton House and its gardens extensively. He became a respected figure in the Scottish art world, though perhaps somewhat removed from the cutting edge as newer movements like Fauvism and Cubism emerged in the early 20th century.

Some critics argue that the demands of the market led to a degree of formulaicism in his later work. The compositions became somewhat predictable, and the initial freshness and experimental energy seen in his earlier paintings, particularly those from the Japanese period and the collaboration with Henry, arguably diminished. He continued to produce variations on his popular themes – girls in landscapes, often with titles like Gathering Primroses or By the Burn. These works, while technically proficient and visually appealing with their "jewel-like" surfaces, sometimes lacked the innovative spark of his earlier output.

Despite this, Hornel remained a highly regarded painter. He continued to travel, including trips back to Australia, and to Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka) and Burma (Myanmar) in 1907 and 1922, which provided fresh inspiration and subject matter, often resulting in works depicting local people and scenes rendered in his characteristic style. He also developed a keen interest in local history and culture, particularly the history of Galloway and Celtic studies, assembling a significant library at Broughton House. This interest occasionally surfaced in his work, linking his decorative landscapes back to the ancient roots explored in The Druids.

Photography as a Tool

An interesting aspect of Hornel's working practice was his use of photography. Like many artists of his time, including Degas and Thomas Eakins, Hornel utilized the camera as an aid mémoire and compositional tool. He took numerous photographs, particularly of the children who modelled for him, capturing poses and groupings that he would later translate into paintings. This practice allowed him to study fleeting expressions and gestures, although his final paintings were far from photographic reproductions.

His paintings transform the photographic source material through his distinctive style – the heightened colour, the thick impasto, the flattened perspective, and the emphasis on decorative pattern. The relationship between his photographs and paintings offers insight into his creative process, showing how he mediated reality through his artistic vision. It also touches upon the broader dialogue between painting and photography in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Furthermore, his photographs taken in Japan and Ceylon provide valuable historical records, while also highlighting, as some analyses suggest, the complexities and potential tensions inherent in a Western artist representing Eastern subjects – the interplay between observation, artistic convention, and cultural perspective.

Broughton House: A Legacy in Kirkcudbright

Hornel's deep connection to Kirkcudbright is cemented by his legacy at Broughton House. He purchased the 18th-century townhouse in 1901 and, over the years, transformed it and its gardens into a reflection of his artistic and personal interests. The house became not only his home and studio but also a repository for his growing collection of books, artworks, and objects gathered on his travels. He took particular pride in the garden, designing it himself with influences from his time in Japan, creating a beautiful space that often featured in his paintings.

His library became one of the most significant private collections in Scotland, particularly strong in works related to Scottish history and literature, especially that of Dumfries and Galloway, including rare editions of Robert Burns. This reflected his deep engagement with the cultural heritage of his adopted region.

Upon his death on June 30, 1933, Hornel bequeathed Broughton House and its contents to the people of Kirkcudbright, intending it to be "for the benefit of the public." His sister, Elizabeth, initially managed the property as a gallery and library. However, maintaining such a significant property and collection proved challenging. Following financial pressures and concerns after a fire, the National Trust for Scotland took over the management of Broughton House in 1997. Today, it remains open to the public, preserving Hornel's studio, his library, examples of his artwork, and the beautiful Japanese-inspired garden, offering a unique window into his life and work. The transfer of management did spark some local debate, highlighting ongoing discussions about the best ways to preserve and manage cultural heritage.

Influence and Critical Standing

Edward Atkinson Hornel's influence lies primarily within the context of Scottish art and the Glasgow School. As a key member of the Glasgow Boys, he contributed to the revitalization of Scottish painting at the end of the 19th century, helping to establish its international reputation. His bold use of colour and decorative approach, particularly after his trip to Japan, pushed the boundaries of the group's aesthetic and aligned Scottish art with broader European trends like Post-Impressionism and Symbolism. His collaboration with George Henry produced iconic works that remain highlights of the movement.

While his later work may have settled into a popular formula, his technical skill, particularly his handling of paint and colour to create rich, textured surfaces, remained impressive. He demonstrated how influences from diverse cultures, especially Japan, could be integrated into a Western painting tradition, contributing to the cross-cultural dialogues prevalent in art at the turn of the century. Artists like Arthur Melville, another Scottish painter known for his travels and vibrant watercolours, shared this interest in depicting foreign lands, though with a different technique.

Today, Hornel is remembered as a master colourist and a significant figure in the Glasgow School. His work is held in numerous public collections, including the National Galleries of Scotland, Glasgow Museums, the Tate in London, and galleries in Aberdeen, Bradford, Buffalo, and Toronto. While contemporary critics might find his recurring depictions of children overly sentimental, his best works are celebrated for their decorative beauty, vibrant energy, and unique fusion of influences. Broughton House stands as a testament to his life, art, and commitment to his community.

Conclusion: A Tapestry of Colour and Culture

Edward Atkinson Hornel's artistic journey was one of exploration – geographical, cultural, and technical. From his beginnings in Australia to his deep roots in Kirkcudbright, his education in Antwerp, his pivotal role in the Glasgow Boys, and his transformative experiences in Japan, Hornel forged a unique artistic identity. His paintings, with their characteristic rich colour, thick impasto, and decorative patterns, capture a world often idealized, filled with the beauty of nature, the innocence of childhood, and echoes of distant cultures. Though sometimes criticized for repetition in his later years, his contribution to Scottish art, his pioneering spirit within the Glasgow School, and his mastery of colour ensure his enduring place in art history. His legacy lives on not only in his vibrant canvases but also in the cultural haven he created at Broughton House, forever linking his name to the artistic heritage of Kirkcudbright and Scotland.