Joseph Hecht stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of 20th-century modern art. A Polish-born artist who found his mature voice in the vibrant artistic milieu of Paris, Hecht was a virtuoso of the engraving medium, particularly renowned for his innovative use of the burin. His work, predominantly focusing on the animal kingdom and natural forms, bridged traditional craftsmanship with modernist sensibilities. He was not only a prolific creator but also a pivotal figure in the revival of original printmaking, most notably through his instrumental role in the founding of the legendary Atelier 17. This exploration delves into the life, art, collaborations, and enduring legacy of Joseph Hecht, an artist whose dedication to his craft left an indelible mark on the history of printmaking.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Poland

Józef Hecht, later known as Joseph Hecht, was born on December 14, 1891, in Łódź, a major industrial city in what was then Congress Poland, part of the Russian Empire. His upbringing was within a Jewish family that, by some accounts, was relatively prosperous, involved in the textile industry that characterized Łódź. This comfortable background likely afforded him the opportunity to pursue his artistic inclinations from a young age.

Hecht's formal artistic training commenced at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych im. Jana Matejki). Between 1912 and 1914, he distinguished himself as a promising student, earning several honors and awards. This period in Krakow would have exposed him to a rich artistic heritage, including the legacy of Polish Symbolism and the burgeoning modern art movements filtering in from Western Europe. The academic training would have provided him with a solid foundation in drawing and composition, skills that would later prove essential to his meticulous engraving work.

Displacement and Formative Travels

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 dramatically altered the course of Hecht's life and career. As a Polish national under German occupation, he was compelled to leave his homeland. He sought refuge in Norway, a neutral country during the conflict. This period of exile, though born of necessity, proved artistically significant. In Norway, Hecht continued to develop his art and, importantly, encountered individuals who would support his endeavors. Among them was John Hecht (no direct relation, it seems, but a shared surname), an art patron who recognized the young artist's talent.

His time in Norway also brought him into contact, or at least proximity, with the powerful expressionistic art of Edvard Munch, who was a towering figure in Scandinavian art. While direct tutelage is not documented, the emotional intensity and stylistic freedom of Munch's work may have resonated with Hecht as he sought his own artistic path.

Following his stay in Norway, Hecht's journey led him to Italy. He traveled extensively, immersing himself in the classical and Renaissance masterpieces of Rome and Florence. This exposure to the Italian masters, with their profound understanding of line and form, likely further honed his aesthetic sensibilities and appreciation for draughtsmanship, a cornerstone of engraving. The rich artistic tapestry of Italy, from ancient sculptures to Renaissance frescoes, would have offered a stark contrast to the more somber tones of Northern European art he had recently experienced.

Arrival in Paris: The Crucible of Modernism

Around 1920, Joseph Hecht arrived in Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. He settled in Montparnasse, the bohemian quarter teeming with artists, writers, and intellectuals from across the globe. This was a period of intense artistic ferment, with Cubism having reshaped pictorial space, Dadaism challenging artistic conventions, and Surrealism beginning to emerge. Hecht quickly integrated into this vibrant community.

His talent was recognized, and he became a member of the Salon d'Automne, an influential annual exhibition that provided a platform for avant-garde artists. Membership in such an esteemed institution was a significant step, granting him visibility and access to the Parisian art world. In Paris, Hecht's artistic identity began to crystallize. While he had experience in painting and sculpture, it was in printmaking, specifically engraving, that he would find his true calling and make his most lasting contributions.

Hecht's circle of acquaintances in Paris included some of the most prominent artists of the era. He is known to have been in contact with Amedeo Modigliani, whose elegant, elongated figures were a hallmark of the School of Paris; Jacques Lipchitz, a leading Cubist sculptor; and Moissey Kogan, a sculptor and printmaker. These interactions, whether casual encounters in the cafes of Montparnasse or more formal artistic exchanges, would have provided intellectual stimulation and a sense of shared purpose within the avant-garde.

The Art of Engraving: Hecht's Technical Mastery

Joseph Hecht became a master of engraving, a demanding intaglio technique where the image is incised directly into a metal plate (usually copper) using a burin, a sharp steel tool. Unlike etching, which uses acid to bite lines into the plate, engraving relies entirely on the artist's manual skill, pressure, and control to create lines of varying width and depth. Hecht embraced the inherent challenges and expressive potential of the burin with remarkable dedication.

His approach to engraving was characterized by a profound understanding of what he termed the "language of the burin." He explored its full expressive range, from long, fluid, gliding lines that could define the sleek contour of an animal, to short, energetic jabs and staccato movements that conveyed texture and dynamism. His technique involved a vocabulary of actions: digging, ploughing, and stabbing into the copper, each mark a deliberate and considered gesture. This direct, physical engagement with the plate imbued his prints with a sense of immediacy and vitality.

Hecht's subject matter was predominantly drawn from the natural world, with a particular fascination for animals. He frequented the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, observing and sketching exotic creatures. His animal depictions are not merely illustrative but are imbued with a sense of character, movement, and often a subtle stylization that aligns with Art Deco and modernist aesthetics. He captured the essence of his subjects – the sinuous grace of a panther, the alert tension of a deer, the powerful form of a bison – with an economy of line and a sophisticated sense of design.

Atelier 17: A Revolution in Printmaking

One of Joseph Hecht's most significant contributions to 20th-century art was his pivotal role in the establishment and spirit of Atelier 17. In 1927, Hecht encountered the British artist Stanley William Hayter. Sources suggest different dynamics in their early relationship: some indicate Hecht taught Hayter the intricacies of burin engraving, while others suggest Hayter, already an experienced printmaker, became a mentor to Hecht in other intaglio techniques like etching and drypoint. It is most likely that their relationship was one of mutual learning and respect, a collaborative exchange of skills and ideas. Hayter himself acknowledged Hecht's profound influence on his understanding of the burin.

Together, they were instrumental in fostering the environment that became Atelier 17, with Hayter formally founding the workshop. Hecht was a key figure in its early years, sharing his expertise and passion for engraving. Atelier 17 was not a traditional art school but an experimental workshop where artists could explore the full potential of intaglio printmaking. It became a melting pot for artists from diverse backgrounds and stylistic persuasions, united by a spirit of innovation.

The workshop attracted an extraordinary roster of artists, many of whom would become giants of modern art. Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, Joan Miró, Alberto Giacometti, Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Wassily Kandinsky, and Jackson Pollock are just some of the luminaries who worked at Atelier 17 at various times, particularly after its relocation to New York during World War II and its subsequent return to Paris. Hecht's early presence and technical mastery helped to establish the workshop's reputation for excellence and experimentation. He championed the idea of the "original print," where the artist was directly involved in every stage of the plate-making and printing process, as opposed to merely reproductive printmaking.

Collaborations, Associations, and Key Works

Beyond Atelier 17, Hecht was active in other artistic circles and engaged in significant collaborations. He was a founding member of "La Jeune Gravure Contemporaine" (The Young Contemporary Engraving) in 1929, alongside artists like Pierre Guastalla, André Jacquemin, and Louis Joseph Soulas (also cited as Louis Joseph Contou in some contexts). This group aimed to promote and exhibit contemporary printmaking, organizing annual shows and fostering a community of printmakers.

A notable collaborative project was the "Atlas" series, undertaken with the French writer André Suarès. This ambitious work, published in 1928, featured Hecht's engravings of maps representing different continents – Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Arctic – each imbued with symbolic animal imagery. The illustrations, rendered in Hecht's characteristic animalist style, often depicted exotic creatures he observed at the Jardin des Plantes, transforming geographical representations into poetic visual meditations.

Another fascinating aspect of his collaborative spirit and technical innovation is exemplified by the print "La Noyée" (The Drowned Woman), created in conjunction with Stanley William Hayter. For this and similar works, Hecht developed a method of cutting up previously engraved copper plates, isolating the animal figures or other elements. These "découpés" (cut-outs) were then inked and arranged, sometimes randomly, on the press bed to create new compositions. He referred to these as "gravure mobile" (mobile engraving), and the resulting prints, often with embossed "gaufré" effects, are prized for their rarity and inventive charm. This technique prefigured later experiments in collage and assemblage in printmaking.

Among Hecht's representative works, several stand out:

"Deer in the Forest" (Cerfs dans la Forêt, c. 1926): An exquisite example of his skill in etching and drypoint, this work captures the alert grace of deer in a stylized woodland setting. The interplay of delicate lines and rich blacks demonstrates his command of intaglio techniques. This piece is held in collections such as the Yale Center for British Art.

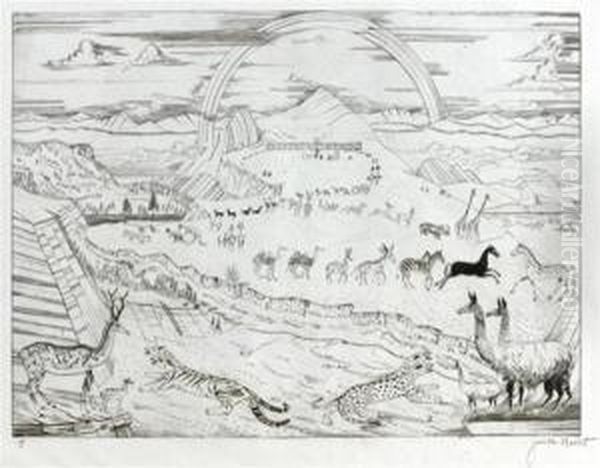

"L'Arche de Noé" (Noah's Ark, 1928): A portfolio of engravings illustrating the biblical story, showcasing his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and narrate through his animal subjects. A version is in the Syracuse University Art Collection.

"Cerfs Indochinois" (Indochinese Deer, 1950): Part of a later series, this print demonstrates his continued dedication to animal subjects and his refined engraving technique. An edition of this work has appeared at auction.

"Ile des cormorans" (Cormorant Island): An illustrated book that combined various printmaking techniques, including etching, woodcut, and lithography, showcasing his versatility.

His oeuvre is characterized by a consistent focus on animal forms, rendered with a blend of naturalistic observation and stylistic elegance. The lines are precise yet fluid, conveying both anatomical accuracy and a sense of vital energy. There's often a decorative quality to his compositions, reminiscent of Art Deco, yet his work transcends mere ornamentation through its technical brilliance and expressive depth. Elements of Surrealism can be discerned in the dreamlike quality of some compositions, while the directness of his mark-making can also evoke Expressionist sensibilities.

Personal Life, Wartime Challenges, and Later Years

Joseph Hecht's personal life in Paris included his marriage to Ingrid Sofia Morssing, a Swedish woman. She was supportive of his artistic career, helping him establish a printing studio in Paris and facilitating his participation in artistic activities. They had a son, Henri Hecht, who later became known as the artist Henri Maïk. However, surviving accounts, possibly from later memoirs, suggest that Hecht experienced some disappointment with aspects of his marriage and family life, a common enough sentiment but one that adds a layer of human complexity to his biography.

As an immigrant artist of Jewish heritage, Hecht faced considerable challenges, including language barriers and economic difficulties, especially in the competitive Parisian art scene. The rise of Nazism and the outbreak of World War II brought new perils. During the Nazi occupation of France, Hecht reportedly engaged in clandestine political activities. There is evidence suggesting his involvement in efforts to help Jewish individuals escape from Southern Europe to the safety of Switzerland. This courageous and dangerous work underscores a profound humanitarian commitment alongside his artistic pursuits.

His experiences during the war, including the horrors of the Holocaust, deeply affected him. This is reflected in his war poetry, which, though less known than his visual art, provides insight into his reflections on conflict and human suffering.

After the war, Hecht continued to work, though perhaps without the same level of public recognition as some of his Atelier 17 colleagues who had achieved international fame. His dedication to the craft of engraving remained unwavering. He died in Paris on July 19, 1951, at the age of 59.

Anecdotes and Unrevealed Facets

While much of Hecht's life revolved around his meticulous studio practice, certain anecdotes and less-publicized aspects enrich his story. His early exile to Norway not only provided safety but also an introduction to the patronage of John Hecht, a crucial early support. His travels in Italy, absorbing the lessons of the Old Masters, undoubtedly informed the linear precision of his engravings.

The very act of co-founding La Jeune Gravure Contemporaine speaks to a desire to build community and advocate for his chosen medium. His collaboration with André Suarès on "Atlas" was a significant undertaking, blending cartography, animal symbolism, and poetic text in a unique livre d'artiste.

The political activities during the Nazi occupation reveal a courageous dimension to his character, risking his own safety to aid others. This commitment to humanitarian values, often unstated in formal art historical accounts, adds significant depth to our understanding of the man behind the art. Even his later reflections on personal disappointments, hinted at in memoirs, offer a glimpse into the inner life of an artist navigating the complexities of life, creativity, and relationships.

His connection with the Swedish painter Isaac Grünewald, for whom he reportedly drew a portrait, indicates his integration into broader European artistic networks beyond the Franco-Polish sphere. The detail that his wife, Ingrid, helped him set up his printing studio highlights the practical and emotional support systems often crucial for artists.

Legacy, Collections, and Market Presence

Joseph Hecht's legacy primarily rests on his exceptional skill as an engraver and his role in the revitalization of original printmaking in the 20th century. Through his work and his influence at Atelier 17, he helped elevate the status of engraving as a fine art medium, demonstrating its capacity for profound artistic expression. He influenced a generation of printmakers, not only through direct teaching but also by example. Artists like the South African printmaker Dolf Rieser explicitly studied engraving with Hecht and at Atelier 17.

His works are held in various public and private collections. The Yale Center for British Art (New Haven, Connecticut) holds pieces like "Deer in the Forest." The Syracuse University Art Collection in New York has his "L'Arche de Noé." Significantly, the Hecht Museum at the University of Haifa in Israel, founded by Reuben Hecht (though the exact familial connection to Joseph, if any, beyond a shared passion for art and heritage, needs careful verification, as Reuben's collection was primarily archaeological and Impressionist/School of Paris), stands as a testament to the Hecht name's association with art and culture, and may hold or have context for Joseph's work.

Hecht's prints appear on the art market, with auction records for works like "Cerfs Indochinois." Historically, his works were exhibited at the Salon d'Automne. The auction house Jac. Hecht in Berlin, active in the 1920s, handled a variety of art and antiques, including prints by European masters; while this may be a different Hecht, it points to the name being associated with the art trade of the period. More specific auction records for Joseph Hecht's works would be found through major auction houses specializing in prints and modern art.

While perhaps not as widely known to the general public as some of his contemporaries like Picasso or Miró, Joseph Hecht's contribution is recognized by connoisseurs of printmaking and art historians. His dedication to the demanding art of engraving, his innovative techniques, and his influential role in fostering a new wave of creative printmaking secure his place in the annals of modern art. His art continues to speak through its exquisite craftsmanship, its sensitive portrayal of the natural world, and its embodiment of the creative spirit of Parisian modernism. He remains a "master's master," an artist whose profound technical skill and unique vision enriched the tapestry of 20th-century art.