Introduction: An Artist Between Worlds

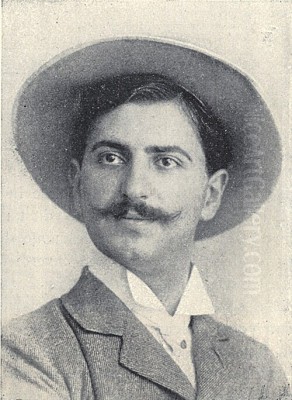

Edgar Chahine (1874-1947) stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in early 20th-century European art. An artist of Armenian heritage who became a naturalized French citizen, Chahine navigated multiple cultural spheres, bringing a unique perspective to his celebrated work, primarily in the demanding medium of printmaking. Born during the twilight of the Ottoman Empire and maturing as an artist in the vibrant atmosphere of Belle Époque Paris, he became renowned for his evocative depictions of modern life, ranging from the elegance of Parisian society to the stark realities faced by the city's poor and marginalized. His technical mastery, particularly in etching and drypoint, earned him international acclaim, positioning him as a key chronicler of his time and a vital link between Armenian artistic identity and the broader currents of French modernism.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Edgar Chahine's story begins not in the artistic centers he would later inhabit, but in Vienna, Austria, on October 31, 1874. His birth occurred while his parents were visiting the spa town of Karlsbad (now Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic). His family background was rooted in the Armenian community of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), the bustling capital of the Ottoman Empire. His father was a prominent figure, serving as a director of the Ottoman Bank, and his mother also hailed from a prosperous banking family. This comfortable upbringing provided the foundation for his later pursuits, although his path would diverge significantly from the world of finance.

Chahine spent his formative years in Constantinople, a city teeming with diverse cultures and stark social contrasts. It was here that his artistic inclinations first surfaced. An early inspiration was his uncle, Melkon Tiratzian, who recognized the young Edgar's talent and encouraged him to pursue formal art education abroad. Following this advice, Chahine initially traveled to Italy, a traditional destination for aspiring artists seeking to immerse themselves in the legacy of the Renaissance and Baroque masters.

His Italian sojourn centered on Venice, a city whose unique atmosphere and artistic heritage would leave a lasting impression on him. He enrolled in the Lycée des Beaux Arts de Venise (often associated with the Mekhitarist Lycée Murat-Raphaël, an important Armenian educational institution in the city). Here, he received rigorous academic training under the guidance of the respected painter Antonio Ermolao Paoletti. This period was crucial for honing his foundational skills in drawing and painting, preparing him for the next major step in his artistic journey.

Arrival in Paris and the Académie Julian

Around the age of 18, seeking broader horizons and the epicenter of the contemporary art world, Chahine left Constantinople. After his formative studies in Venice, he made the pivotal decision to move to Paris in 1895. Paris during the Belle Époque (roughly 1871-1914) was the undisputed capital of art and culture, attracting ambitious talents from across the globe. The city pulsed with creative energy, innovation, and a dynamic social scene that would become the primary subject matter for Chahine's work.

To further refine his skills and integrate into the Parisian art milieu, Chahine enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian. This private art school was a renowned alternative to the more conservative École des Beaux-Arts, known for its liberal atmosphere and diverse student body. It was a crucible of emerging talent, and Chahine found himself studying alongside individuals who would become major figures in modern art. His contemporaries at the Académie Julian reportedly included artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Villon, Édouard Vuillard, Henri Matisse, and the sharp social commentator Jean-Louis Forain.

Studying in this environment exposed Chahine to a wide range of artistic ideas and techniques. While he continued to paint, it was during his early years in Paris that he began to seriously explore the possibilities of printmaking, particularly etching and drypoint. The city itself, with its grand boulevards, intimate cafés, bustling markets, and hidden corners, provided an inexhaustible source of inspiration. He quickly absorbed the spirit of the age, developing a keen eye for observing the nuances of Parisian life.

Rise to Prominence: A Belle Époque Printmaker

Chahine's talent did not go unnoticed for long. He began exhibiting his work publicly soon after arriving in Paris. His debut at the prestigious Paris Salon occurred in 1896 with a piece titled "Portrait of a Beggar." This early work already hinted at his interest in depicting subjects often overlooked by more conventional artists – the city's less fortunate inhabitants. This focus on social realism would become a recurring theme throughout his career.

His breakthrough came with a series of prints exhibited in 1899, collectively known as "La Vie Lamentable" (The Miserable Life). This powerful series unflinchingly portrayed the lives of the poor, the homeless, and the downtrodden on the streets of Paris. These works resonated with critics and the public alike, showcasing not only Chahine's technical skill but also his profound empathy and sharp observational powers. The series was a critical success and cemented his reputation as a significant new voice in the Parisian art scene.

The recognition culminated in a major honor: a Gold Medal for his prints at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) held in Paris in 1900. This international event brought immense visibility to his work. Further accolades followed, including another Gold Medal at the prestigious Venice Biennale in 1903. Within less than a decade of arriving in Paris, Edgar Chahine had established himself as one of the leading printmakers of the Belle Époque, admired for both his technical virtuosity and the compelling humanism of his subjects.

Themes and Subjects: The Spectacle of Parisian Life

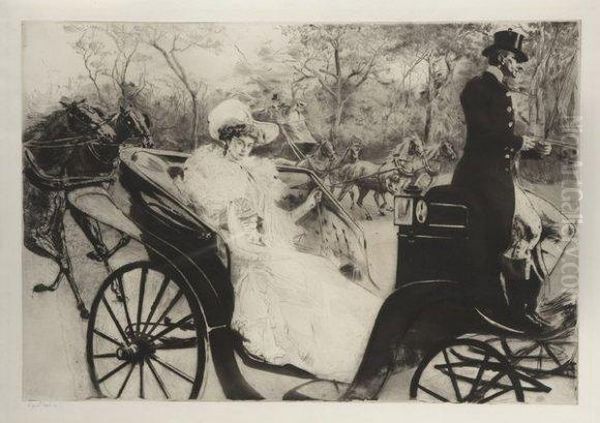

Edgar Chahine's oeuvre provides a rich tapestry of Parisian life during the Belle Époque. His work captures the era's characteristic blend of elegance, dynamism, and underlying social tensions. He was fascinated by the spectacle of the modern city in all its facets. On one hand, he depicted the fashionable world of the Parisian elite – elegant women strolling along the boulevards, attending soirées, or enjoying leisurely moments in parks and cafés. Works like the large etching "La Promenade" (1902) exemplify this aspect, capturing the grace and movement of figures in stylish attire.

Simultaneously, Chahine maintained a deep engagement with the lives of ordinary Parisians and the city's marginalized populations. His "La Vie Lamentable" series is the most prominent example, but this interest persisted throughout his career. He depicted street vendors, beggars, acrobats, circus performers ("String Dancer," 1906), and laborers with sensitivity and dignity, avoiding sentimentality while highlighting their humanity. His book project "Fêtes foraines de Paris" (Parisian Street Fairs) further explored the world of popular entertainment and the people who inhabited it.

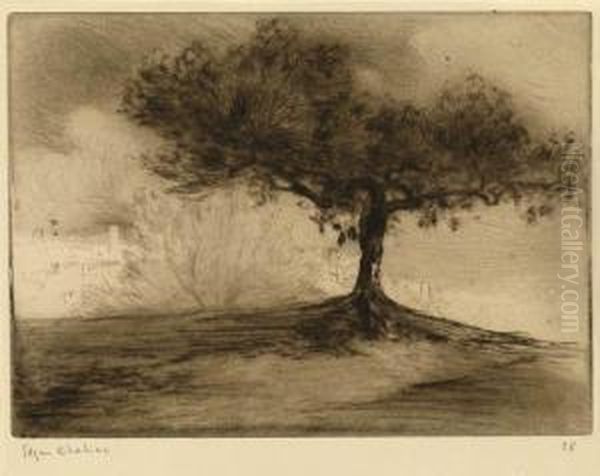

This duality is central to understanding Chahine's artistic vision. He was both an observer of high society and a chronicler of the streets, capturing the contrasts and complexities of modern urban existence. His Armenian background, perhaps giving him an outsider's perspective, may have contributed to his empathy for those on the fringes of society. Venice also remained a recurring theme in his work, revisited in later prints that captured the unique atmosphere of the Italian city he had known in his youth, often focusing on its canals and architecture.

Mastery of Printmaking Techniques

While Chahine also worked as a painter, his most significant contribution lies in the field of printmaking. He demonstrated exceptional proficiency across various intaglio techniques, primarily etching, drypoint, and occasionally aquatint and soft-ground etching. His choice of medium was perfectly suited to his subject matter, allowing for both delicate detail and expressive tonal contrasts.

He was particularly renowned for his mastery of drypoint. In this technique, the artist scratches directly onto the copper plate with a sharp needle, creating a groove that holds the ink. The displaced metal forms a rough edge called a "burr" alongside the line. When inked and printed, the burr imparts a characteristic soft, velvety, and rich black line, ideal for rendering textures like fur, fabric, or deep shadows. Chahine exploited the potential of drypoint to create atmospheric effects and convey emotional depth.

His etchings, created by drawing through a wax ground on the plate and then using acid to bite the lines, often display remarkable precision and fluidity. He skillfully combined etching with drypoint and aquatint – a process that creates tonal areas rather than lines – to achieve a wide range of effects, from subtle gradations of light to dramatic chiaroscuro. His sophisticated use of light and shadow is a hallmark of his style, effectively conveying mood, volume, and the specific ambiance of a scene, whether it be the dimly lit interior of a café or the bright sunlight of a Parisian park.

Key Works and Illustrations

Several works stand out in Edgar Chahine's extensive printmaking oeuvre. The "La Vie Lamentable" series (1896-1899) remains fundamental, establishing his reputation for social commentary and technical skill. "La Promenade" (1902) is a masterful example of his ability to capture the elegance and movement of Belle Époque society on a large scale. "String Dancer" (or "Danseuse de Corde," 1906) vividly portrays the energy and precariousness of street performers.

Beyond individual prints, Chahine was also a sought-after book illustrator. He created illustrations for works by prominent contemporary French writers, bringing his visual interpretations to their texts. Among the authors whose books he illustrated were Maurice Barrès, the influential novelist and politician; Octave Mirbeau, known for his socially critical novels and plays; and the esteemed writer Anatole France, with whom Chahine developed a close friendship. These collaborations placed him at the intersection of literature and visual art, further enhancing his standing in the cultural landscape of the time.

He also produced his own illustrated books, such as "Fêtes foraines de Paris" and "Impressions d'Italie," which allowed him to explore specific themes in depth through a series of related images. Another notable work mentioned is "La Catastrophe de Fourvière" (1930), a woodcut possibly depicting a tragic event, showcasing his versatility across different printmaking techniques, including relief printing. These projects demonstrate his sustained engagement with narrative and thematic development through series of prints.

Recognition, Awards, and Connections

Chahine's artistic achievements garnered significant recognition throughout his career. Following his early successes with the Gold Medals at the Paris Exposition Universelle (1900) and the Venice Biennale (1903), he continued to exhibit widely and receive accolades. He was a regular participant in the Venice Biennale, showcasing his work there again in 1907, 1914, and notably winning another Gold Medal in 1926, demonstrating his enduring relevance even as artistic styles began to shift dramatically after World War I.

His prominence in the French art world was formally acknowledged in 1932 when he was awarded the Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honour), one of France's highest civilian decorations. This award underscored his successful integration into French cultural life and the esteem in which his work was held. He had become a naturalized French citizen several years earlier, in 1925, solidifying his ties to his adopted country.

Beyond official recognition, Chahine maintained connections within the artistic and literary communities. His time at the Académie Julian placed him in contact with future luminaries like Duchamp, Villon, Vuillard, and Matisse. His friendship with Anatole France highlights his links to the literary world. His work can be contextualized alongside other artists who depicted Parisian life and employed printmaking, such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, known for his posters and portrayals of Montmartre nightlife; James McNeill Whistler, an influential etcher; Edgar Degas, with his interest in dancers and modern subjects; and Pierre Bonnard and Félix Vallotton, fellow printmakers associated with the Nabis group who also studied at Julian. Chahine carved his own niche within this vibrant scene, distinguished by his technical focus and blend of social observation.

Armenian Identity and Cultural Bridge

Throughout his life and career in France, Edgar Chahine maintained a connection to his Armenian heritage. While his subject matter was predominantly Parisian, his background inevitably shaped his perspective. Some interpretations suggest that his focus on marginalized figures and his empathetic portrayal of poverty stemmed, in part, from his identity as a member of a diaspora community with a history of displacement and persecution. His engagement with Armenian community affairs in Paris, including reported involvement in socialist activities related to the Armenian cause, indicates a continued commitment to his roots.

His success provided visibility for Armenian artists on the international stage. He became one of the most prominent artists of Armenian descent working in Europe during his time. His ability to achieve recognition within the highly competitive Parisian art world while retaining aspects of his cultural identity served as an inspiration. He effectively acted as a cultural bridge, demonstrating how an artist could navigate and contribute to multiple cultural contexts.

While overt Armenian themes are not the dominant feature of his most famous works, his identity remained an integral part of his story. His work is often included in surveys of Armenian art, and institutions like the National Gallery of Armenia in Yerevan hold significant collections of his prints, acknowledging his importance within the narrative of Armenian cultural history as well as French art history.

Later Career, Challenges, and Loss

The period following World War I and the end of the Belle Époque marked a gradual shift in Chahine's career trajectory. While he continued to work and exhibit, receiving honors like the Legion of Honour and the 1926 Venice Biennale Gold Medal, the artistic landscape was changing rapidly with the rise of Cubism, Surrealism, and other avant-garde movements. The specific style and subject matter that had brought him fame during the Belle Époque perhaps resonated less strongly in the interwar years.

His later career was also marked by significant personal tragedy and loss related to his artistic output. In 1926, a fire broke out in his studio, destroying a vast number of his prints and, crucially, many of the original copper plates from which they were made. This meant that editions of these works could no longer be printed, rendering the surviving impressions even rarer. Disaster struck again in 1942 when a flood damaged his workshop, leading to further losses of prints and potentially more plates.

These events dealt a severe blow to his legacy, making a comprehensive overview of his work challenging and contributing to his relative obscurity compared to some contemporaries whose oeuvres survived more intact. Despite these setbacks, he continued to create art. He remained in Paris through the difficult years of the German occupation during World War II. Edgar Chahine passed away in Paris in 1947, leaving behind a body of work marked by both brilliance and tragic loss.

Legacy and Collections

Despite the challenges and the loss of a significant portion of his work, Edgar Chahine's legacy endures. He is remembered as a master printmaker whose technical skill, particularly in drypoint and etching, was exceptional. His work provides an invaluable visual record of Parisian life during the Belle Époque, capturing its elegance, energy, and social complexities with a unique blend of sensitivity and realism. He stands out for his ability to portray both the fashionable elite and the city's underclass with equal insight and artistry.

His prints are held in major public collections around the world, attesting to their enduring quality and historical importance. Notable institutions housing his work include the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris, the National Gallery of Armenia in Yerevan, the British Museum in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and numerous other museums and print rooms specializing in works on paper.

Chahine's contribution lies not only in his artistic output but also in his position as an artist bridging cultures. He successfully integrated into the French art world while maintaining connections to his Armenian heritage, becoming a significant figure in the histories of both French and Armenian art. His work continues to be studied and appreciated for its technical mastery, its evocative portrayal of a bygone era, and its profound humanism.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Edgar Chahine was more than just a skilled technician; he was an artist with a distinct vision and a deep connection to the human condition. Through his meticulous prints, he captured the fleeting moments and enduring truths of life in one of the world's great cities during a period of profound social and cultural transformation. From the glittering surfaces of high society to the shadowed corners inhabited by the poor, his work offers a nuanced and compelling portrait of the Belle Époque. Though tempered by the tragic loss of much of his oeuvre, the surviving prints of Edgar Chahine stand as a testament to his mastery and ensure his place as a significant chronicler of his time and a master of modern printmaking.