Joseph Walter West (1860-1933) stands as a notable figure in the landscape of late Victorian and Edwardian British art. A painter and illustrator of considerable skill, West carved a niche for himself with his evocative figurative works, often imbued with literary or historical narratives, and a particular affinity for depicting Quaker subjects. His mastery of watercolour further distinguished him, earning him a respected position within the Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours. Though perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, West's contributions to British art are significant, reflecting both the academic traditions of his training and a subtle engagement with the evolving artistic currents of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in the bustling port city of Kingston upon Hull in Yorkshire, England, Joseph Walter West emerged into a world where artistic training was becoming increasingly formalized and accessible. His foundational artistic education took place at the St. John's Wood Art School in London, an institution known for preparing students for entry into the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. This early grounding would have emphasized rigorous drawing skills, a cornerstone of academic art.

West's talent evidently flourished, as he successfully gained admission to the Royal Academy Schools. Here, he would have been immersed in a curriculum that prized historical painting, portraiture, and classical ideals. The influence of figures like Sir Frederic Leighton, then President of the Royal Academy, and Lawrence Alma-Tadema, with their meticulously rendered historical and classical scenes, would have been pervasive. Students were encouraged to master anatomy, perspective, and composition, often drawing from plaster casts of classical sculptures before progressing to life models.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, West, like many aspiring artists of his generation, traveled to Paris. He enrolled at the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that offered a more liberal alternative to the official École des Beaux-Arts. The Académie Julian attracted a diverse international student body and was known for its emphasis on figure drawing and painting from life. Instructors there, such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Tony Robert-Fleury, were themselves highly successful academic painters. This Parisian sojourn exposed West to different pedagogical approaches and the vibrant, competitive art scene of the French capital, which was then a crucible of artistic innovation, with Impressionism having already made its mark and Post-Impressionist movements beginning to stir.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Joseph Walter West's oeuvre is characterized by a dedication to figurative art, often drawing inspiration from literature, history, and everyday life, particularly scenes with a quiet, narrative quality. His style, while rooted in the academic tradition of careful draughtsmanship and balanced composition, also shows a sensitivity to light and atmosphere that suggests an awareness of Impressionistic trends, albeit filtered through a distinctly British sensibility.

A unique and recurring theme in West's work is his depiction of Quaker life. The Society of Friends, or Quakers, with their emphasis on simplicity, pacifism, and inner spiritual experience, provided a rich source of subject matter that was somewhat unusual in the mainstream art world of the time. These paintings often convey a sense of calm, introspection, and communal harmony, rendered with a sympathetic and respectful eye. This focus set him apart from many contemporaries who might have favored more dramatic or overtly sentimental Victorian narratives, such as those by Luke Fildes or Frank Holl.

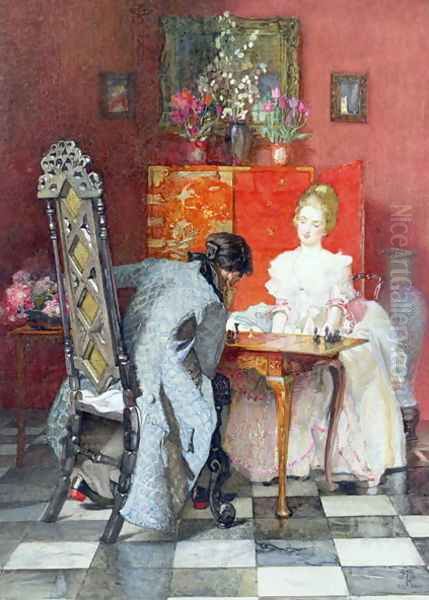

Beyond his Quaker subjects, West explored broader literary and historical themes. His painting An Eighteenth Century Idyll, for instance, points to an interest in period settings and romanticized interpretations of the past, a popular genre in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Artists like Marcus Stone were also known for such charming historical genre scenes. West's ability to convey narrative through gesture, expression, and carefully chosen details was a hallmark of his figurative compositions. He also produced landscapes, though he is perhaps less known for these than for his figure paintings.

Mastery in Watercolour

While accomplished in oils, Joseph Walter West was particularly celebrated for his skill in watercolour. He became a prominent member of the Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours (RWS), eventually serving as its Vice-President. The RWS, founded in 1804, had a long and distinguished history, championing watercolour as a serious artistic medium. West's involvement signifies his high standing among his peers in this demanding field.

His watercolour technique often involved precise drawing combined with luminous washes of colour. The provided information notes his use of pencil and watercolour, sometimes augmented with white bodycolour (gouache) for highlights and a "scratching out" technique. Scratching out involves carefully removing pigment from the paper surface to reveal the white paper underneath, creating fine highlights or textural effects. This was a technique also skillfully employed by earlier watercolour masters like J.M.W. Turner. West's dedication to watercolour placed him in a lineage of great British watercolourists, from early pioneers like Paul Sandby and Thomas Girtin to Victorian masters such as Myles Birket Foster and Helen Allingham, who also excelled in capturing the nuances of British life and landscape in this medium.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

Several works by Joseph Walter West are mentioned, offering glimpses into his artistic output. Portrait of a Lady, dated around 1900, is described as a "Victorian Impressionist" piece. This suggests a work that, while retaining a strong sense of likeness and Victorian propriety, likely incorporated looser brushwork, a brighter palette, or a greater concern for capturing the fleeting effects of light than was typical of purely academic portraiture. British Impressionism, championed by artists like Philip Wilson Steer and Walter Sickert (though Sickert's style was often darker and more urban), sought to adapt French Impressionist principles to British tastes and subjects. West's portrait may have reflected this nuanced engagement.

Another titled work is Black to Move, created in 1920. While specific details about its subject matter or style are not provided in the initial information, the title itself is intriguing. It could allude to a game of chess, a common metaphor for strategic thinking or a pivotal moment, or it might have a more symbolic or narrative meaning. Given West's penchant for literary and figurative themes, it was likely a narrative painting. By 1920, the art world had seen the advent of Cubism, Fauvism, and other modernist movements, but many established artists like West continued to work in more traditional, representational styles, albeit sometimes inflected with newer sensibilities.

An Eighteenth Century Idyll is also mentioned, specifically in the context of it being gifted by West to an R.W.S. Winter in 1928. The title evokes a romanticized scene from the Georgian era, a period often viewed with nostalgia. Such works appealed to a taste for elegance, charm, and a perceived simpler past. The act of gifting the work suggests a personal connection or patronage, common in artistic circles.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Professional Affiliations

Joseph Walter West was an active participant in the British art world, regularly exhibiting his work at prestigious venues. He showed at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, the premier exhibition space in Britain. Acceptance into the RA's annual Summer Exhibition was a significant mark of professional achievement and provided artists with crucial exposure to patrons and critics. He also exhibited with the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA), another important exhibiting society that offered an alternative platform for artists.

His most significant affiliation, however, appears to have been with the Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours (RWS). His rise to the position of Vice-President underscores his dedication to the medium and the esteem in which he was held by his fellow watercolourists. Membership in such societies was vital for artists, providing not only exhibition opportunities but also a community of peers, professional support, and a collective voice in the art world. The art scene of his time was characterized by a network of such societies, each with its own focus and membership, including groups like the New English Art Club, which often showcased more progressive, Impressionist-influenced work by artists such as John Singer Sargent (an American who became a dominant figure in British portraiture) and George Clausen.

Contextualizing West: His Place in British Art

Joseph Walter West's career spanned a period of significant transition in British art. He began his training when the high Victorian academic tradition, with its emphasis on narrative, detail, and moral content, was at its zenith. Figures like William Powell Frith, known for his sprawling modern-life panoramas, or George Frederic Watts, with his allegorical and symbolist paintings, represented different facets of this era.

As West matured, the influence of French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism began to permeate British art, leading to the emergence of groups like the Camden Town Group in the early 20th century, with artists such as Spencer Gore and Harold Gilman, who explored more radical approaches to colour and form. While West's work generally remained within a more traditional representational framework, his "Victorian Impressionist" portrait suggests an openness to these evolving aesthetics.

His focus on Quaker themes is particularly noteworthy. It offered a counterpoint to the often grandiloquent or overtly sentimental subjects favored by some of his contemporaries. This choice aligns with a broader interest in genre scenes and depictions of everyday life, but with a specific cultural and spiritual dimension that was uniquely his. In this, he perhaps shared a certain sensibility with artists who focused on rural life or specific communities, though his subject was more defined by faith than by geography or occupation alone.

The period also saw a flourishing of illustration, and many painters, including Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac, achieved fame through their book illustrations. While the provided information focuses on West's paintings, artists of his training often undertook illustrative work as well, given the strong emphasis on narrative and draughtsmanship.

Legacy and Collections

The inclusion of Joseph Walter West's works in public collections such as the Tate, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, and the National Galleries of Scotland attests to his recognized artistic merit and historical importance. These institutions play a crucial role in preserving and presenting the nation's artistic heritage, and the acquisition of an artist's work by such galleries ensures its accessibility to future generations for study and appreciation.

His legacy lies in his contribution to the tradition of British figurative painting and watercolour. He successfully navigated the academic system, absorbed influences from his studies at home and abroad, and developed a distinctive voice, particularly through his depictions of Quaker life. As Vice-President of the RWS, he also played a role in upholding the status and promoting the practice of watercolour painting in Britain.

While the provided information does not detail specific interactions with contemporary painters or direct artistic lineage through students, his active participation in major exhibiting societies like the RA, RBA, and RWS implies a professional life lived within a community of artists. The art world of London was, and is, a relatively close-knit environment, and artists would have encountered each other at exhibitions, society meetings, and social gatherings. His contemporaries at the Royal Academy might have included painters like Solomon J. Solomon or Sir Frank Dicksee, who also worked in figurative and narrative styles.

Conclusion

Joseph Walter West was an accomplished British artist whose career bridged the late Victorian era and the early decades of the 20th century. Trained in the rigorous academic traditions of London and Paris, he developed a refined style characterized by strong draughtsmanship, a sensitive handling of narrative, and a particular aptitude for watercolour. His depictions of Quaker subjects offer a unique window into a specific aspect of British cultural life, rendered with empathy and skill.

While he may not have been an avant-garde revolutionary, West was a dedicated and respected painter who contributed meaningfully to the artistic fabric of his time. His works, preserved in national collections, continue to speak of a commitment to craftsmanship, a thoughtful engagement with his chosen themes, and a mastery of his preferred media. He remains a figure worthy of study for those interested in the rich and diverse tapestry of British art during a period of profound social and artistic change, standing alongside other skilled representational painters of his era such as Stanhope Forbes of the Newlyn School, who also focused on depictions of everyday community life, albeit in a different regional context. Joseph Walter West's art provides a quiet yet compelling testament to a life devoted to the pursuit of pictorial beauty and narrative depth.