Marie Spartali Stillman stands as one of the most significant female artists associated with the second wave of the Pre-Raphaelite movement in Britain. A woman of striking beauty, formidable intellect, and profound artistic talent, she navigated the complex social and artistic currents of Victorian England and beyond, leaving behind a legacy of over 150 works characterized by their lyrical beauty, meticulous detail, and deep engagement with literature and myth. Her life and art offer a fascinating window into the world of the Pre-Raphaelites, the challenges faced by women artists, and the enduring power of a singular creative vision.

Early Life and Hellenic Heritage

Born Maria Euphrosyne Spartali on March 10, 1844, in Hornsey, Middlesex, London, she was the eldest daughter of Michael Spartali, a wealthy Greek merchant and later the Greek Consul-General in London from 1866 to 1882. Her mother, Euphrosyne Varsami, was also of Greek origin. The Spartali family was part of a vibrant and influential Anglo-Greek community in London, known for its affluence, cultural sophistication, and patronage of the arts. Marie and her sisters, Christine and Demetria, were renowned for their beauty and were often referred to collectively as "the Three Graces," becoming sought-after subjects for artists within their circle.

Growing up in a household that valued culture and education, Marie was exposed to art and literature from a young age. The family home, "The Shrubbery" on Clapham Common, and later their residence at 22 Cleveland Square, Hyde Park, were hubs of social and artistic activity. This environment undoubtedly nurtured her innate artistic sensibilities. She received a privileged education, typical for young women of her class, which would have included languages, music, and drawing. Her Greek heritage also played a significant role, instilling in her a deep appreciation for classical mythology and history, themes that would later permeate her artwork.

Entry into the Pre-Raphaelite Circle

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) had been founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, with the aim of rejecting the Royal Academy's mechanistic approach to art, which they believed was derivative of late Renaissance masters like Raphael. They advocated for a return to the intense colours, abundant detail, and complex compositions of Quattrocento Italian and Flemish art. By the late 1850s and early 1860s, when Marie Spartali was coming of age, the original PRB had largely dissolved, but its ideals continued to inspire a new generation of artists, often referred to as the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism.

It was through her family's social connections that Marie Spartali entered this intoxicating artistic milieu. The Spartalis were acquainted with prominent figures like James McNeill Whistler and Algernon Charles Swinburne. Her striking appearance – tall, with classical features, abundant dark hair, and an enigmatic gaze – perfectly embodied the Pre-Raphaelite ideal of female beauty. She quickly became a favoured model for several leading artists of the day.

Whistler, an American expatriate artist known for his aestheticism, was one of the first to recognize her potential as a model, featuring her in his "La Princesse du pays de la porcelaine" (1863-1865), a key work in his exploration of Japonisme. However, it was her association with Dante Gabriel Rossetti that most firmly placed her within the Pre-Raphaelite orbit. Rossetti, a charismatic and influential figure, was captivated by her beauty, seeing in her a successor to his earlier muses like Elizabeth Siddal and Jane Morris. She posed for several of his works, including "A Vision of Fiammetta" (1878) and studies for "Dante's Dream at the Time of the Death of Beatrice" (1871).

Edward Burne-Jones, another leading figure of the second Pre-Raphaelite generation, also frequently enlisted her as a model. Her features can be discerned in works such as "The Mill" (1870-1882) and studies for "The Golden Stairs" (1880). Julia Margaret Cameron, the pioneering Victorian photographer, captured her ethereal beauty in a series of striking photographic portraits around 1868, further cementing her image as a Pre-Raphaelite "stunner."

Artistic Training and Development

While her role as a model provided her with invaluable access to artists' studios and their working methods, Marie Spartali harboured ambitions of becoming an artist in her own right. This was a challenging path for women in the Victorian era, as formal art education at institutions like the Royal Academy Schools was largely inaccessible or offered limited training to female students. However, her family's wealth and social standing allowed her to pursue private tuition.

From 1864, she began to study under Ford Madox Brown, an artist closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, known for his historical subjects and moral intensity. Brown was a demanding but supportive teacher, and under his guidance, Spartali honed her technical skills, particularly in drawing and composition. He encouraged her to study from life and to develop her own distinct voice. She also received informal guidance from Rossetti, who, despite his often-overwhelming influence, recognized her talent.

Spartali Stillman primarily worked in watercolour, a medium often favoured by female artists of the period, partly due to its perceived suitability for "feminine" subjects and partly because it was more manageable for artists working from home studios. However, she pushed the boundaries of the medium, achieving a richness of colour, depth of tone, and meticulous detail that rivalled oil painting. Her technique involved layering transparent washes of colour, often with the addition of bodycolour (gouache) for highlights and opacity, creating luminous and jewel-like surfaces.

Her early works, exhibited from the mid-1860s, already showed a strong Pre-Raphaelite influence in their choice of subject matter – often drawn from literature, legend, and romantic poetry – and their emphasis on decorative detail and emotional intensity. She exhibited regularly at prestigious venues such as the Dudley Gallery, which was known for showcasing watercolour art, and later at the Grosvenor Gallery, a more progressive alternative to the Royal Academy, founded by Sir Coutts Lindsay and his wife Blanche.

Themes and Subject Matter

Marie Spartali Stillman's oeuvre is characterized by a consistent engagement with literary and mythological themes, often imbued with a sense of romantic melancholy and yearning. Her deep knowledge of literature, particularly English and Italian poetry, provided a rich wellspring of inspiration.

Shakespearean subjects were a recurring feature, with works like "Mariana" (inspired by "Measure for Measure") and "The Gentle Mercies of the Wicked" (illustrating a line from "The Merchant of Venice"). Dante Alighieri was another profound influence, reflecting the Pre-Raphaelite fascination with the Italian poet. Her painting "Madonna Pietra degli Scrovegni" (1884) is a haunting depiction of Dante's "stony lady," a figure from his "Rime Petrose," embodying cold, unrequited love. This work, with its cool palette and the figure's remote expression, perfectly captures the essence of the poetic source.

Italian Renaissance literature, particularly the works of Petrarch and Boccaccio, also provided fertile ground. "A Florentine Lily" (c. 1885-90) and "A Rose from the Garden of Armida" (1894), the latter inspired by Torquato Tasso's epic poem "Gerusalemme Liberata," showcase her ability to evoke the romantic and chivalric atmosphere of these texts. Her figures are often depicted in enclosed gardens or richly decorated interiors, settings that enhance the sense of intimacy and introspection.

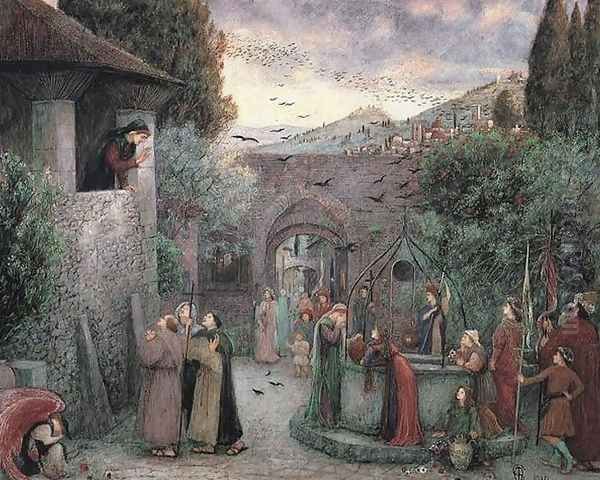

Mythological subjects, both classical and medieval, allowed her to explore themes of love, loss, and enchantment. "The Enchanted Garden of Messer Ansaldo" (1889), based on a tale from Boccaccio's "Decameron," is a particularly fine example, depicting a magical garden conjured to win a lady's love. The meticulous rendering of flowers and foliage, a hallmark of Pre-Raphaelite naturalism, is evident in this work.

Beyond literary and mythological scenes, Spartali Stillman also painted portraits and, significantly, landscapes. Her time spent in Italy, particularly after her marriage, led to a series of evocative depictions of Italian scenery, often imbued with the same romantic sensibility as her figurative works. These landscapes, such as "The Orange Grove, Bordighera" or "View from the Villa Palmieri, Florence," are not mere topographical records but rather mood pieces, capturing the light and atmosphere of the Italian countryside.

Marriage to William James Stillman

In 1871, Marie Spartali married William James Stillman (1828-1901), an American journalist, diplomat, photographer, and art critic. Their marriage was a love match, but it was not without its complexities and challenges. William Stillman was a widower with three children from his previous marriage, and he was a somewhat restless and often controversial figure. His career as a foreign correspondent for "The Times" and other publications meant frequent moves, and the couple lived in various locations, including Florence and Rome, before eventually settling in Surrey, England, in their later years.

Marie's parents initially disapproved of the match, perhaps due to Stillman's less stable financial situation and his somewhat unconventional background. However, Marie was determined, and the marriage went ahead. She became a devoted stepmother to Stillman's children and later had three children of her own: Euphrosyne (Effie), Michael, and William.

The demands of family life, coupled with her husband's peripatetic career, undoubtedly placed constraints on her artistic production. In a letter from 1873, she mentioned being "too weak to paint" due to anxieties about her family's health. However, she never abandoned her art. Indeed, her time in Italy profoundly influenced her work, providing her with new subjects and a deeper connection to the Renaissance art she so admired. She continued to paint and exhibit throughout her married life, often sending works back to London for exhibition.

William Stillman, himself an artist in his youth and a knowledgeable art critic, was generally supportive of his wife's career, although some biographers suggest there may have been an undercurrent of professional jealousy. He certainly recognized her talent, and his connections in the art world may have been beneficial. However, Marie's primary artistic identity remained rooted in the Pre-Raphaelite circle she had established before her marriage.

Representative Works: A Closer Look

Several of Marie Spartali Stillman's works stand out as particularly representative of her style and thematic concerns.

"Love's Messenger" (1885), now in the Delaware Art Museum, is one of her most iconic paintings. It depicts a pensive young woman in a medieval-style interior, receiving a message from a dove, a traditional symbol of love and fidelity. The rich colours, the detailed rendering of fabrics and flowers, and the figure's melancholic expression are all hallmarks of her Pre-Raphaelite sensibility. The composition, with its shallow space and emphasis on pattern, recalls early Renaissance art. The work exudes an atmosphere of quiet contemplation and romantic longing.

"Madonna Pietra degli Scrovegni" (1884), housed in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, is a powerful interpretation of Dante's "stony lady." The figure, clad in cool blues and greys, gazes out with an impassive, almost challenging expression. The background features a meticulously rendered cityscape, possibly alluding to Florence. The painting's emotional coolness and the strength of the female figure are notable, perhaps reflecting Spartali Stillman's own resilience.

"The Meeting of Dante and Beatrice on All Saints' Day" (1880s) is another significant Dante-inspired work. It captures the pivotal moment from Dante's "Vita Nuova" where he encounters Beatrice. The figures are rendered with a delicate grace, and the Florentine setting is carefully detailed. The painting conveys the spiritual and transformative nature of Dante's love for Beatrice, a theme central to Pre-Raphaelite iconography.

"A Rose from the Garden of Armida" (1894) illustrates an episode from Tasso's "Gerusalemme Liberata," where the sorceress Armida creates an enchanted garden to ensnare the Christian knight Rinaldo. Spartali Stillman focuses on a moment of quiet beauty, with a richly dressed figure holding a rose, a symbol of love and beauty, but also of transience. The lush, detailed foliage and the figure's contemplative mood are characteristic.

Her landscapes, such as "Italian Garden with Cypresses and Olive Trees" (c. 1880s), demonstrate her skill in capturing the unique light and atmosphere of Italy. These works often feature classical architectural elements or typically Mediterranean flora, rendered with the same attention to detail and sensitivity to mood as her figurative paintings.

Artistic Circle and Influences

Throughout her career, Marie Spartali Stillman remained connected to a wide circle of artists and writers. Her early mentors, Ford Madox Brown and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, were crucial in shaping her artistic direction. She maintained lifelong friendships with many figures from the Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic movements.

Edward Burne-Jones was a particularly close friend and admirer of her work. His own art, with its emphasis on dreamlike medievalism and elongated, graceful figures, shared certain affinities with hers. William Morris, the designer, poet, and socialist activist, was another important figure in her circle. His firm, Morris & Co., revolutionized Victorian decorative arts, and its emphasis on craftsmanship and medieval aesthetics resonated with Pre-Raphaelite ideals. Spartali Stillman's attention to decorative detail and pattern in her paintings reflects this shared sensibility.

She was also acquainted with other prominent artists of the period, such as George Frederic Watts, a leading Symbolist painter, and Val Prinsep, another artist associated with the later Pre-Raphaelites. Her connection with Julia Margaret Cameron highlights the cross-pollination between painting and the burgeoning art of photography in the Victorian era.

The influence of early Italian Renaissance painters, such as Sandro Botticelli and Fra Angelico, is evident in her work, particularly in the clarity of her compositions, the lyrical grace of her figures, and her use of luminous colour. Like many Pre-Raphaelites, she looked to these earlier masters as an antidote to what they perceived as the academicism of later art.

Later Career and Legacy

Marie Spartali Stillman continued to paint and exhibit into the early 20th century. Her style remained largely consistent, rooted in the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic, though some later works show a slightly looser handling and a greater emphasis on atmospheric effects, particularly in her landscapes. She exhibited at the New Gallery, which succeeded the Grosvenor Gallery as a venue for progressive art, and also in America, where her work was well-received, particularly in cities like Boston and Philadelphia.

Despite the challenges of balancing her artistic career with family responsibilities and frequent moves, she produced a substantial body of work. Her dedication to her art, in an era when professional careers for women were still the exception, is a testament to her passion and determination.

Marie Spartali Stillman died on March 6, 1927, in Ashburnham Grove, South Kensington, London, just four days shy of her 83rd birthday. For many years after her death, like many Pre-Raphaelite artists, her work fell somewhat out of fashion as modernism came to dominate the art world. However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen a significant revival of interest in Pre-Raphaelite art, and with it, a renewed appreciation for Spartali Stillman's contribution.

She is now recognized as one of the most talented and prolific female artists of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Her work is admired for its technical skill, its poetic sensibility, and its distinctive vision. Exhibitions dedicated to Pre-Raphaelite women artists have brought her work to a wider audience, highlighting her importance alongside contemporaries like Evelyn De Morgan and Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale. Her paintings are held in major public collections in the UK and the USA, including the Delaware Art Museum, the Walker Art Gallery, the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, and the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Marie Spartali Stillman's art offers a unique blend of Pre-Raphaelite intensity, classical grace, and a deeply personal romanticism. Her ability to translate complex literary and mythological narratives into visually compelling images, rendered with exquisite detail and luminous colour, secures her place as a significant figure in 19th-century British art. Her life story, as both a celebrated muse and a dedicated artist, continues to inspire, reminding us of the enduring power of beauty, intellect, and creative perseverance. Her legacy is not just in the beautiful objects she created, but in the example she set as a woman who successfully forged an artistic career in a male-dominated world, leaving an indelible mark on the landscape of art history.