Joža Uprka stands as a pivotal figure in Czech art, celebrated for his vivid and ethnographic depictions of the folk life, traditions, and landscapes of Moravian Slovácko. His work, deeply rooted in his homeland, not only captured the unique cultural heritage of this region but also engaged with broader European artistic currents, creating a distinctive style that continues to resonate. This exploration delves into the life, art, and enduring legacy of a painter who became synonymous with the soul of his people.

Early Life and Formative Education

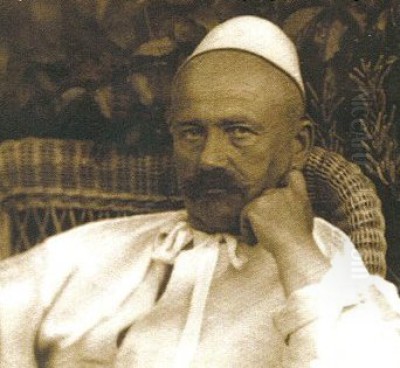

Josef "Joža" Uprka was born on October 26, 1861, in the village of Kněždub, nestled in the heart of Moravian Slovácko, a region then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and now within the Czech Republic. This area, bordering Slovakia, was rich in distinct folk traditions, colorful costumes, and a strong sense of local identity, all of which would become the cornerstone of Uprka's artistic oeuvre. His upbringing in this environment instilled in him a profound appreciation for the rural way of life and its cultural expressions.

His formal artistic training began at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. However, Uprka found the conservative academicism prevalent there under professors like František Čermák somewhat stifling. Seeking a more progressive environment, he moved to the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich in 1884. Munich at that time was a significant European art center, offering exposure to various emerging trends. Here, he studied under figures such as Nikolaos Gyzis and possibly came into contact with the work of artists associated with the Munich Secession, though the Secession itself would formally emerge a bit later. The Munich experience broadened his technical skills and artistic horizons, yet his heart remained tethered to his homeland.

Return to Slovácko and Artistic Immersion

After completing his studies in Munich around 1887, Uprka made a conscious decision to return to Moravian Slovácko. This was not merely a return home but a deliberate artistic choice. He settled in Hroznová Lhota, a village that became his base and a constant source of inspiration. Unlike many contemporaries who might have sought careers in major urban art centers like Prague or Vienna, Uprka dedicated himself to becoming the visual chronicler of his specific region.

His deep connection to the local people and their customs allowed him an intimate perspective. He wasn't an outsider observing quaint traditions; he was part of the community, understanding the nuances of their festivals, religious processions, daily labor, and social gatherings. This immersion was crucial to the authenticity and vibrancy that characterize his paintings. He lived among the farmers, artisans, and villagers, sketching them in their everyday environments and during special occasions.

The Influence of Impressionism and Plein Air

A significant turning point in Uprka's artistic development was his exposure to French Impressionism. He traveled to Paris, likely in the early 1890s, where he encountered the revolutionary works of artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. The Impressionists' emphasis on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and atmosphere, and their use of a brighter palette and broken brushstrokes profoundly impacted Uprka.

He began to incorporate these techniques into his own work, moving away from the darker tones and tighter rendering of his academic training. Plein air painting became a hallmark of his practice. He would set up his easel outdoors, directly observing his subjects in their natural light, whether it was the brilliant sunshine illuminating a festive crowd or the softer light of a rural landscape. This approach lent an immediacy and vibrancy to his canvases, making the colors sing and the scenes come alive. His adaptation of Impressionist techniques was not a mere imitation but a fusion with his deep-seated interest in ethnographic detail and narrative.

Art Nouveau and Decorative Sensibilities

Alongside Impressionism, Uprka's style also shows affinities with Art Nouveau, or "Secesija" as it was known in Central Europe. This is particularly evident in his strong sense of design, his use of flowing lines, and the decorative qualities of his compositions, especially in the rendering of the elaborate folk costumes of Slovácko. The intricate embroidery, vibrant patterns, and rich textures of these garments provided a natural subject for an artist with a decorative sensibility.

Artists like Alfons Mucha, a fellow Moravian who achieved international fame with his Art Nouveau posters, shared a similar interest in Slavic heritage and decorative aesthetics, albeit expressed in different mediums and contexts. Uprka's work, while primarily focused on painting, often has a tapestry-like quality, where the figures and their attire form a rich, patterned surface. This decorative aspect, combined with his Impressionistic handling of light and color, created a unique visual language.

Themes and Subjects: The Soul of Slovácko

Uprka's thematic focus was unwavering: the people and culture of Moravian Slovácko. His paintings are a comprehensive visual encyclopedia of the region's life. He depicted religious pilgrimages, such as the famous processions to the Chapel of Saint Anthony of Padua near Blatnice, a recurring and iconic theme in his work. These scenes are filled with crowds of figures in their finest traditional dress, capturing the spiritual fervor and communal spirit of such events.

Festivals and folk customs were another major subject. The "Ride of the Kings" (Jízda králů), a vibrant Pentecost tradition, was a spectacle he painted multiple times, showcasing the color, movement, and pageantry of the event. He also painted scenes of everyday life: markets, harvests, village gatherings, women at work in the fields or at home, and men in conversation. These were not idealized pastoral scenes but lively depictions of real people engaged in their daily routines and celebrations. The accuracy in depicting the specific costumes of different villages and age groups within Slovácko is a testament to his meticulous observation.

Representative Masterpieces

Several of Uprka's works stand out as iconic representations of his artistic vision and his beloved Slovácko.

Pouť u sv. Antonínka (Pilgrimage at St. Anthony's Chapel): This is perhaps his most famous and frequently revisited theme. Various versions exist, all capturing the vibrant procession of pilgrims in their colorful folk attire making their way to the chapel. The paintings are characterized by a dynamic composition, a brilliant palette, and a masterful handling of light that seems to shimmer across the scene, imbuing it with an almost spiritual luminescence. The sheer number of figures, each individually suggested yet part of a collective whole, demonstrates his skill in managing complex compositions.

Jízda králů (The Ride of the Kings): Another signature theme, these paintings depict the dramatic and colorful folk custom where young men on horseback, adorned with ribbons and traditional decorations, parade through the village. Uprka captures the energy and excitement of the event, the pride of the participants, and the rich visual spectacle of the horses and costumes.

Trh v Kyjově (Market in Kyjov): Scenes of local markets allowed Uprka to depict a cross-section of village life, with people buying, selling, and socializing. These works are bustling with activity and offer a glimpse into the economic and social fabric of the community. The varied costumes and the lively interactions between figures are rendered with his characteristic vibrancy.

Ženy při draní peří (Women Plucking Feathers): Beyond large festive scenes, Uprka also painted more intimate depictions of daily life. This subject, showing women gathered for the communal task of plucking feathers (often for bedding), highlights the social aspects of work and the quiet dignity of rural labor.

His dedication to these themes was so profound that his name became almost interchangeable with the artistic representation of Slovácko. He was, in essence, the region's painter laureate.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Connections

Uprka's work gained significant recognition both within the Czech lands and internationally. He exhibited regularly in Prague, often at the Topič Salon, a prominent venue for contemporary art. His participation in the 1893 Paris Salon, where he received an honorable mention, marked an important moment of international acknowledgment. He also exhibited in Vienna, Berlin, and other European cities, bringing the unique culture of Slovácko to a wider audience.

He was an active member of the Mánes Union of Fine Arts, a progressive association of Czech artists. Within this circle, he interacted with leading figures of Czech modernism, such as the painter Antonín Slavíček, known for his lyrical landscapes, and the sculptor Stanislav Sucharda. Uprka also maintained a friendship with the painter and graphic artist Zdenka Braunerová, who shared an interest in folk art and culture.

Uprka was a founding member of the "Škréta" association of Czech students in Munich, which later evolved. This group included notable artists like Alfons Mucha, Luděk Marold (known for his panoramic paintings), and Pavel Sochán. These connections fostered a supportive network and an exchange of ideas among Czech artists studying abroad.

His home in Hroznová Lhota, designed by the renowned Slovak architect Dušan Jurkovič—who himself was a master of incorporating folk motifs into modern architecture—became a cultural hub. It attracted visits from writers, artists, and intellectuals, including the famous French sculptor Auguste Rodin, whom Uprka invited to witness the folk traditions of Slovácko firsthand in 1902. This visit underscores Uprka's role as a cultural ambassador for his region.

While his style was distinct, Uprka's dedication to national themes can be seen in parallel with other European artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries who sought inspiration in their own folk cultures, such as Anders Zorn in Sweden, Ilya Repin in Russia, or even earlier figures like Mikoláš Aleš in the Czech lands, who also extensively documented Czech history and folklore, albeit in a more illustrative style. Uprka's approach, however, was uniquely filtered through an Impressionistic lens.

Style and Technique: A Synthesis

Uprka's mature style is a compelling synthesis of keen ethnographic observation, Impressionistic light and color, and an Art Nouveau-inflected decorative sense. His brushwork is often energetic and visible, contributing to the vibrancy of his surfaces. He had a remarkable ability to capture the dazzling array of colors found in Slovácko folk costumes—the brilliant reds, yellows, blues, and whites—without them becoming chaotic. Instead, he harmonized these colors under the unifying effects of natural light.

His compositions are often dynamic, filled with figures in motion or arranged in lively groups. He masterfully handled crowd scenes, giving a sense of individual presence within the collective. The play of sunlight and shadow is a key element, creating depth and highlighting textures, particularly the intricate details of embroidery and fabrics. He was less interested in precise, photographic realism and more focused on conveying the overall atmosphere, energy, and visual splendor of the scenes he witnessed. His use of color was not just descriptive but also expressive, conveying the joy and vitality of the folk culture he cherished.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Joža Uprka continued to paint prolifically throughout his life, remaining dedicated to his chosen subjects. He became an iconic figure, deeply respected in his homeland. He passed away on January 12, 1940, in Hroznová Lhota, the village that had been his home and endless inspiration.

After his death, like many artists whose work is strongly tied to a specific style or period, Uprka's reputation experienced fluctuations. However, his importance as a chronicler of a unique cultural heritage and as a significant Czech painter of his generation has endured. His works are held in major Czech galleries, including the National Gallery Prague and the Moravian Gallery in Brno, as well as in regional collections.

In recent decades, there has been a renewed appreciation for his art. Exhibitions of his work continue to draw audiences, and his paintings are studied for their artistic merit as well as their ethnographic value. In 2011, a school was named in his honor, a testament to his lasting cultural significance. His art serves as a vibrant, irreplaceable record of the folk traditions of Moravian Slovácko, many of which have changed or diminished with the passage of time.

Collectors like George T. Duesler helped bring his work to attention in places like the United States, further broadening his posthumous recognition. His influence can also be seen in subsequent generations of artists from the region who continued to explore local themes, though perhaps with different stylistic approaches.

Conclusion: The Painter of the Moravian Soul

Joža Uprka was more than just a painter of folk scenes; he was a passionate advocate and preserver of a unique cultural identity. Through his canvases, vibrant with color, light, and life, he captured the essence of Moravian Slovácko, its people, and its traditions. By skillfully blending influences from major European art movements like Impressionism and Art Nouveau with his deep personal connection to his homeland, he created a body of work that is both artistically compelling and historically invaluable.

His legacy extends beyond the art world; it is intertwined with the cultural memory of the Czech nation. Uprka's paintings are a celebration of community, tradition, and the enduring beauty of folk culture, ensuring that the spirit of Slovácko, as he saw and loved it, continues to inspire and enchant. He remains a beloved figure, a true "painter of the Moravian soul," whose art offers a luminous window into a world rich in color and heritage. His contemporaries, such as the landscape Impressionist Antonín Slavíček or the Symbolist Max Švabinský, explored different facets of Czech identity, but Uprka's dedicated focus on the ethnographic vitality of Slovácko carved a unique and indelible niche in the history of Czech art.