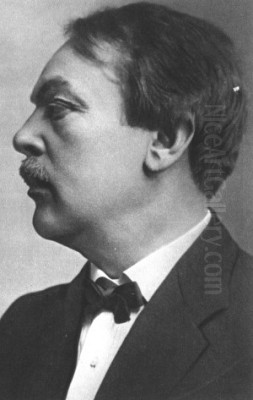

Alois Kalvoda stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of Czech art history, particularly renowned for his contributions to landscape painting at the turn of the 20th century. Born in 1875 and active until his passing in 1934, Kalvoda navigated a period of profound artistic change in Europe. He skillfully synthesized emerging modern styles, notably Impressionism and Art Nouveau, with a deep-seated appreciation for the natural beauty of his homeland. His work not only captured the visual essence of the Czech and Moravian landscapes but also resonated with the burgeoning national identity of the time. Beyond his prolific output as a painter, Kalvoda was also a respected art educator and writer, further cementing his influence on subsequent generations of artists.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Prague

Alois Kalvoda's journey into the world of art began in Šlapanice near Brno, Moravia, where he was born on May 15, 1875. His formal artistic training took place in Prague, the vibrant cultural heart of Bohemia. Between 1892 and 1898, he enrolled at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie výtvarných umění v Praze, AVU). This period was crucial for his development, primarily due to his studies under the tutelage of Professor Julius Mařák.

Mařák was himself a master of landscape painting, heading a specialized landscape school within the Academy that trained many prominent Czech artists. His own style was rooted in late Romanticism, often imbuing landscapes with a sense of moodiness, grandeur, and historical resonance. While Kalvoda studied diligently under Mařák, the direct influence of his teacher's Romantic style on his mature work proved relatively limited and transient.

However, the pedagogical approach of Mařák's school left a more lasting imprint. Emphasis was placed on direct observation of nature, plein air sketching, and understanding the underlying structure and atmosphere of the landscape. These foundational principles, focusing on capturing the truth of nature, would underpin Kalvoda's artistic practice throughout his career, even as his stylistic preferences evolved significantly. His time at the Academy placed him amidst a generation of talented landscape painters emerging from Mařák's studio, including figures like František Kaván, Antonín Slavíček, and Otakar Lebeda, setting the stage for a dynamic period in Czech art.

The Parisian Catalyst and Stylistic Metamorphosis

A pivotal moment in Kalvoda's artistic development occurred in 1900 when he was awarded the Hladký Travel Scholarship. This enabled him to journey to Paris, the undisputed epicenter of the art world at the time. The experience was transformative. In Paris, Kalvoda encountered firsthand the revolutionary works of the French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. He absorbed the lessons of artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, particularly their focus on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and atmosphere, and their use of vibrant color and broken brushwork.

This exposure marked a decisive break from the more traditional, often darker palettes and emotionally charged atmospheres favored by the Romantic tradition he had known in Prague. The following year, in 1901, Kalvoda extended his travels to Munich. Germany's art scene, particularly in Munich, was alive with the energy of Jugendstil, the German variant of Art Nouveau. This likely reinforced his growing interest in decorative composition, stylized forms, and the symbolic potential of nature.

These experiences abroad fundamentally reshaped Kalvoda's artistic vision. He began to move away from the purely atmospheric or narrative landscapes associated with his training. Instead, he embraced a brighter palette, a more direct engagement with the optical effects of light, and a style that blended Impressionistic observation with the decorative sensibilities and symbolic undertones of Art Nouveau. This synthesis would become the hallmark of his mature work.

Defining the Kalvoda Style: Impressionism, Symbolism, and the Czech Soul

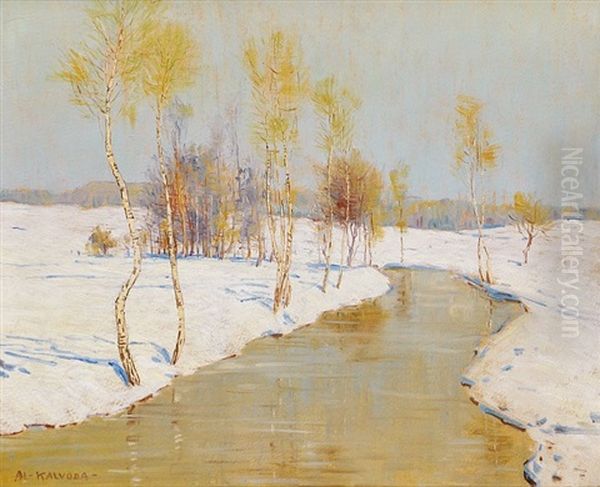

Alois Kalvoda forged a distinctive artistic style that, while clearly indebted to international trends like Impressionism and Art Nouveau, remained deeply rooted in the Czech landscape. His primary subject matter was the countryside of Bohemia and Moravia – its forests, meadows, ponds, and rolling hills. He developed a particular fondness for certain motifs, most notably birch trees, which became almost a signature element in his oeuvre.

His approach combined the Impressionist fascination with light and color with an Art Nouveau emphasis on decorative pattern and line. He excelled at capturing the play of sunlight filtering through leaves, reflections shimmering on water surfaces, and the vibrant hues of different seasons. His palette was often characterized by bright, clear colors, applied with varying brushwork – sometimes using the distinct dabs associated with Impressionism, other times employing smoother passages to define form and create decorative effects.

Unlike some French Impressionists who focused almost exclusively on optical sensations, Kalvoda often imbued his landscapes with a subtle lyricism and symbolic resonance, characteristic of the Art Nouveau ethos. The recurring motif of slender birch trees, often depicted in groves, carried connotations of purity, resilience, and the specific character of the Slavic landscape. His compositions were carefully structured, balancing realistic observation with a strong sense of design and decorative harmony. This unique blend distinguished him from contemporaries like Antonín Slavíček, whose work leaned more heavily towards a purely atmospheric Impressionism, and from the earlier generation influenced by Antonín Chittussi's realism.

Signature Motifs and Representative Works

Kalvoda's prolific output centered on capturing the diverse beauty of the Czech landscape through his unique stylistic lens. Certain themes and specific works stand out as representative of his artistic achievements. His paintings often feature tranquil forest interiors, sun-dappled meadows, quiet ponds reflecting the sky, and the distinctive rolling terrain of the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands.

Among his well-known works is Pond Surrounded by Forest. This painting likely exemplifies his ability to capture atmosphere through light and reflection, detailing the intricate patterns of trees and water while maintaining an overall sense of peaceful seclusion. Another key work often cited is Blue Cypresses, suggesting a piece where color and form might carry symbolic weight, perhaps exploring mood or a more stylized interpretation of nature, possibly influenced by Symbolist currents within Art Nouveau.

His numerous depictions of birch trees, such as paintings simply titled Birch Trees or similar variations, are central to his legacy. These works showcase his mastery of rendering the delicate, silvery bark and fluttering leaves, often set against vibrant blue skies or the rich greens of summer meadows. They highlight his characteristic bright palette and decorative sensibility. The painting Krajina (Landscape) broadly represents his dedication to the Czech countryside, potentially depicting specific regional features or architectural elements within the natural setting, viewed through his Impressionist-influenced perspective. Kalvoda frequently returned to themes like winter landscapes, capturing the subtle beauty of snow-covered fields and bare trees, demonstrating his versatility across different seasons and moods.

A Dedicated Educator and Voice in Art

Alois Kalvoda's influence extended beyond his own canvases; he was also a committed educator and an active participant in the Czech art discourse. Following the dissolution of Julius Mařák's specialized landscape school at the Prague Academy of Fine Arts, Kalvoda recognized the need for continued focused training in this genre. In 1900, he established his own private painting school in Prague.

His school quickly gained popularity and attracted numerous students eager to learn his modern approach to landscape painting, which synthesized Impressionist techniques with Art Nouveau aesthetics. He proved to be an influential teacher, guiding a new generation of artists. Perhaps his most famous pupil was Martin Benka, who would go on to become a foundational figure in modern Slovak painting, carrying forward some of Kalvoda's stylistic tendencies, particularly the blend of observation and decorative stylization, into his depictions of the Slovak landscape and people.

Kalvoda was also a prolific writer and critic. He contributed numerous articles on art to journals like Čas. Between 1909 and 1912, he served as the editor for the important art magazine Dílo (Work), using this platform to publish exhibition reviews and engage in critical debates about contemporary art. Furthermore, he authored several books, including memoirs such as Přátelé výkreslů (Friends of Drawings, 1929) and Vzpomínky (Memories, 1932). These writings provide valuable insights into his artistic philosophy and offer glimpses into the social and cultural milieu of the Prague art world, documenting his interactions and friendships with other key figures of the era.

Navigating the Czech Art Scene: Contemporaries and Connections

Alois Kalvoda operated within a vibrant and dynamic Czech art scene, interacting with, influencing, and being influenced by numerous contemporaries. His initial connection was through his teacher, Julius Mařák, placing him in the lineage of a significant school of landscape painting. This connected him, at least by shared background, with fellow Mařák students like František Kaván, Antonín Slavíček, Otakar Lebeda, Josef Ullmann, and Stanislav Lolek, even though their artistic paths diverged.

His relationship with František Kaván is particularly noteworthy. Both were prominent landscape painters emerging from Mařák's influence and both were also influenced by the earlier realism of Antonín Chittussi. However, their styles differed significantly; Kaván often pursued a more emotionally charged, atmospheric realism, sometimes bordering on Expressionism, while Kalvoda embraced the brighter palette and decorative qualities of Impressionism and Art Nouveau. This difference likely created a dynamic of comparison, if not direct competition, within the Czech art market.

As a leading proponent of a Czech interpretation of Impressionism, Kalvoda's work can be compared to that of Antonín Slavíček, another major figure who absorbed Impressionist lessons. While both focused on light and landscape, Slavíček's approach is often considered more purely atmospheric and perhaps less stylized than Kalvoda's. Kalvoda's student, Martin Benka, represents a direct line of influence into Slovak art.

Beyond landscape specialists, Kalvoda was contemporary to major figures in other fields of Czech art. Alfons Mucha was the internationally renowned master of Art Nouveau, and while their focus differed (Mucha primarily on decorative arts and posters), they shared the stylistic language of the era. Jan Preisler was a leading Symbolist painter, and Max Švabinský was a versatile artist excelling in portraiture and graphic arts. Other notable landscape painters active during parts of Kalvoda's career included Antonín Hudeček. Kalvoda's memoirs suggest friendships and interactions within this broader artistic community, reflecting his established position.

Anecdotes and Cultural Footprint

While detailed personal anecdotes about Alois Kalvoda are not abundant in easily accessible sources, certain aspects highlight his integration into the cultural life of his time. One interesting record mentions his creation of a painting for Stopka's Pilsner Pub in Brno. This artwork reportedly depicted local society figures, suggesting Kalvoda's engagement with the social scene beyond the confines of landscape painting and the art world elite. Such commissions, often capturing the likenesses of patrons or local celebrities, were not uncommon and place the artist within the everyday cultural fabric of the city.

His decision to open a private school after the closure of the Academy's landscape department speaks to his entrepreneurial spirit and his commitment to fostering landscape painting. The school's success indicates both a demand for such training and Kalvoda's reputation as a capable teacher and prominent artist. His role as an editor and writer further underscores his active participation in shaping artistic discourse in Bohemia.

Kalvoda achieved considerable recognition and commercial success during his lifetime. His appealing style, which captured the beauty of the Czech homeland in a modern yet accessible manner, found favor with collectors and the public. His works were widely exhibited both domestically and internationally, contributing to the growing reputation of Czech art abroad. His name became synonymous with a particular vision of the Czech landscape – bright, lyrical, and often centered on the beloved motif of birch trees.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

Alois Kalvoda occupies a significant and respected place in the history of Czech art. He is primarily recognized as one of the leading figures who introduced and adapted modern European artistic currents, particularly Impressionism and Art Nouveau, to the specific context of Czech landscape painting. He effectively bridged the gap between the 19th-century traditions, represented by his teacher Mařák, and the burgeoning modernism of the early 20th century.

His key achievement lies in developing a distinctive style that successfully blended the Impressionist focus on light, color, and atmospheric effects with the decorative composition, stylized lines, and symbolic undertones of Art Nouveau. This synthesis resulted in works that were both visually appealing and resonated with contemporary tastes, while remaining deeply connected to the natural environment of his homeland. His depictions of the Czech landscape, especially his signature birch groves, became iconic and highly popular.

Kalvoda's influence extended through his teaching activities, most notably shaping the early career of the important Slovak artist Martin Benka. His writings and editorial work also contributed to the artistic dialogue of his time. While perhaps not as radical an innovator as some of the avant-garde artists who followed him, Kalvoda played a crucial role in modernizing Czech landscape painting and popularizing a lyrical, optimistic vision of the national countryside. His works remain highly valued by collectors and institutions, appreciated for their technical skill, aesthetic charm, and historical significance as representations of a key period in Czech art.

Conclusion

Alois Kalvoda remains an enduring figure in Czech art, celebrated for his masterful landscape paintings that captured the essence of the Bohemian and Moravian countryside through a modern lens. His skillful integration of Impressionist light and color with Art Nouveau design and symbolism created a unique and appealing style that resonated widely during his lifetime and continues to be admired today. As a prolific artist, influential teacher, and active participant in the cultural life of his era, Kalvoda made substantial contributions to the development of Czech modern art. His legacy is preserved in his numerous canvases, particularly his beloved depictions of birch forests, which stand as lyrical testaments to his artistic vision and his deep connection to the natural world of his homeland.