Józef Rapacki stands as a significant figure in the history of Polish art, renowned primarily for his evocative landscape paintings that captured the unique atmosphere and natural beauty of his homeland. Born in Warsaw in 1871 and passing away in 1929, Rapacki's life spanned a period of immense change in Poland and Europe, and his art reflects both a deep connection to tradition and an engagement with contemporary artistic currents. He dedicated his career to depicting the fields, forests, marshes, and rural scenes of Poland, becoming particularly celebrated for his portrayals of woodland interiors and specific floral motifs.

His work, often imbued with a quiet melancholy or a serene peacefulness, bridges the gap between detailed Realism and the emotional depth of Symbolism and Romanticism. Through his sensitive handling of light, colour, and atmosphere, Rapacki invited viewers into the intimate corners of the Polish countryside, establishing himself as a master of landscape painting whose legacy continues to resonate.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

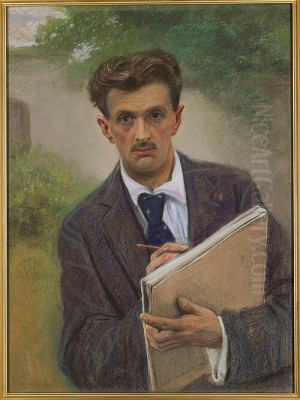

Józef Rapacki was born into a family deeply involved in the arts, though primarily in theatre. His father, Wincenty Rapacki, was a respected actor, and other family members also pursued careers on the stage. This artistic environment likely fostered Józef's own creative inclinations from a young age. However, his path led not to the theatre but to the visual arts. His formal artistic education began in his native Warsaw.

At the age of fourteen, Rapacki enrolled in the Warsaw Drawing School (Klasa Rysunkowa), a crucial institution for aspiring artists in Russian-partitioned Poland. There, he studied under the tutelage of Wojciech Gerson (1831-1901), a leading figure of Polish Realism and a highly influential teacher. Gerson emphasized meticulous observation, solid drawing skills, and often encouraged patriotic themes rooted in Polish history and landscape, foundations that would serve Rapacki well throughout his career.

Further Studies and Influences

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Rapacki moved to Kraków, then under Austrian rule and a vibrant centre of Polish cultural life. He continued his studies at the Kraków School of Fine Arts (Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych). His instructors there included Florian Cynk (1838-1912), Izydor Jabłoński (1835-1905), and Feliks Żyła-rostowski. These teachers further honed his technical abilities within the academic tradition prevalent at the time.

The next significant step in Rapacki's development was his time in Munich, a major European art hub, particularly attractive to artists from Central and Eastern Europe. From 1889 to 1891, he studied at the private school of the German painter Friedrich Fehr (1862-1927). Munich was known for its strong school of Realism, often characterized by dark palettes and meticulous detail. Rapacki absorbed these influences, refining his realistic technique. He would have been aware of the many Polish artists working in Munich, forming the so-called "Munich School" of Polish painters, such as Józef Brandt (1841-1915) and Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski (1849-1915), known for their historical and genre scenes, though Rapacki's focus remained primarily on landscape.

Return to Poland and Artistic Style

Rapacki returned to Poland around 1891, bringing with him a solid academic grounding and exposure to contemporary European art trends. He settled initially near Kraków before eventually moving to Olszanka, a village near Skierniewice, in 1907. This rural setting would become his home and a constant source of inspiration for the rest of his life. His artistic style evolved, blending the precise observation learned from Gerson and in Munich with a more personal, lyrical, and atmospheric approach.

His work is often categorized within the broad streams of Realism and Symbolism, with strong undercurrents of Romanticism. Some critics referred to his style as a form of "living Romanticism," suggesting a continuation of Romantic sensibilities regarding nature's emotional power, expressed through a realistic lens. He excelled at capturing specific times of day and weather conditions, using light and shadow to create mood and evoke feeling. His landscapes are rarely just topographical records; they are imbued with emotion, often a sense of gentle melancholy, peace, or the quiet majesty of nature.

Signature Themes: Forests and Woodlands

Forest interiors became one of Rapacki's most characteristic subjects. He possessed a remarkable ability to render the complex interplay of light filtering through leaves, the textures of tree bark, and the damp atmosphere of the forest floor. Birch trees, with their distinctive white bark, appear frequently, often depicted in groves or standing sentinel at the edge of a clearing.

His forest scenes are not wild, untamed wildernesses but often portray the more managed or accessible woodlands typical of the Polish countryside. He captured the changing seasons within the forest, from the fresh greens of spring to the golden hues of autumn and the stark beauty of winter snow. These works convey a deep intimacy with the woodland environment, suggesting careful and prolonged observation.

Signature Themes: Marshes and Water

Another recurring motif in Rapacki's oeuvre is the depiction of marshes, ponds, and riverside landscapes. These works often possess a particularly strong Symbolist quality, using the reflective surfaces of water and the misty atmosphere of wetlands to create evocative, sometimes melancholic moods. He was adept at painting the subtle colours of dusk and dawn over these watery landscapes.

Paintings like Mokradła w Mrożach (Marshes in Mrozy, 1902) exemplify this theme. The stillness of the water, the silhouettes of trees against the sky, and the muted colour palette contribute to a sense of quiet contemplation. These scenes often feel timeless, capturing the enduring character of the Polish landscape away from the bustle of human activity.

Signature Themes: Flowers and Rural Life

Rapacki gained particular renown for his paintings featuring specific flowers, most notably purple rhododendrons (often referred to as azaleas or sometimes tulips in descriptions, though visually closer to rhododendrons) and bluebells (dzwonce). These floral elements were not mere botanical studies but were integrated into broader landscape compositions, often adding symbolic weight or a vibrant splash of colour. His painting Dzwonce nad leśnym jeziorem (Bluebells by the Forest Lake, 1912) is considered one of his masterpieces, showcasing his skill in combining detailed floral rendering with an atmospheric lakeside setting.

Beyond pure landscape, Rapacki also painted scenes incorporating elements of rural life – thatched cottages, country roads, windmills, and occasionally figures engaged in simple activities. These works, like WIATRAK (Windmill, 1914), celebrate the traditional Polish countryside and its connection to nature, often presented with a nostalgic or idyllic sensibility, characteristic of much Polish art during the period of partitions.

Notable Works and Recognition

Several paintings stand out as representative of Józef Rapacki's style and thematic concerns:

Dzwonce nad leśnym jeziorem (Bluebells by the Forest Lake, 1912): A quintessential Rapacki work, combining his love for forest settings, water, and specific floral motifs into a harmonious and atmospheric composition.

Moorland Evening: This painting showcases his mastery of colour and mood, using a palette dominated by blues and greens, punctuated by touches of red and yellow, to create a dreamlike, tranquil scene typical of his Symbolist-leaning landscapes.

A Summer Meadow (1928): Demonstrates his skill in capturing the effects of light and shadow on a bright summer day, bringing the landscape to life with vibrant yet controlled brushwork.

Nocturne - Church with the Figure of St. John Nepomuk (1918): An example of his nocturnes, where he explored the challenges of painting low light conditions, creating scenes filled with mystery and quiet spirituality.

Mokradła w Mrożach (Marshes in Mrozy, 1902): An early example of his fascination with wetland landscapes, emphasizing atmosphere and reflection.

WIATRAK (Windmill, 1914): Represents his engagement with motifs of rural architecture and life within the landscape.

Rapacki achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime. He exhibited his works frequently in Poland, notably with the Warsaw-based "Pro Arte" society, an association of artists promoting modern Polish art. He also participated in international exhibitions, including shows in Berlin and Paris, where he reportedly received an award at a major international exposition, attesting to his reputation beyond Poland's borders. His work was included in significant surveys, such as the Polish artists' exhibition in 1900.

Context: Polish Art at the Turn of the Century

Józef Rapacki worked during the period often referred to as Young Poland (Młoda Polska), roughly spanning the 1890s to 1918. This era saw a flourishing of Polish arts and literature, marked by Symbolism, Art Nouveau, and a renewed interest in Polish folklore and landscape as expressions of national identity under foreign rule. While Rapacki's style remained more rooted in Realism than some of the leading figures of Young Poland, his work shares the movement's emphasis on mood, atmosphere, and the emotional significance of the Polish landscape.

He was a contemporary of major figures like Stanisław Wyspiański (1869-1907), Jacek Malczewski (1854-1929), Józef Mehoffer (1869-1946), and Leon Wyczółkowski (1852-1936). While artists like Malczewski explored complex national allegories through Symbolism, and Wyspiański created visionary dramas and designs, Rapacki carved his niche through a more direct, though equally poetic, engagement with nature. His focus on landscape also aligns him with other specialists in the genre, such as Jan Stanisławski (1860-1907), known for his smaller, expressive landscape studies, though Rapacki generally worked on a larger scale and with more detailed realism.

Life in Olszanka and Later Career

In 1907, Rapacki settled permanently in Olszanka, where he built a house and studio. This rural retreat provided him with the peace and direct access to nature that fueled his art for the remainder of his life. His paintings from this period often depict the landscapes immediately surrounding his home, imbued with a sense of deep familiarity and affection.

Some sources mention his involvement with artistic institutions following Poland's regaining of independence in 1918, potentially including a role at an art academy, though details remain somewhat unclear. It is certain, however, that he remained an active figure in the Warsaw art scene through groups like Pro Arte.

While his core style remained consistent, some later critical assessments noted a tendency towards repetition in his motifs and compositions, and occasionally a more formulaic or artificial quality compared to the freshness of his earlier work. Nonetheless, even in his later years, he continued to produce works admired for their technical skill and evocative power, such as A Summer Meadow from 1928.

Legacy and Collections

Józef Rapacki died in Olszanka in 1929. He left behind a substantial body of work that secured his place as one of Poland's most beloved landscape painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His primary legacy lies in his ability to capture the specific character and poetic atmosphere of the Polish countryside, particularly its forests and wetlands. He offered a vision of nature that was both realistically observed and emotionally resonant, contributing significantly to the tradition of landscape painting in Poland.

His works are held in major Polish museum collections, most notably the National Museum in Warsaw, which includes his paintings in its collection of modern Polish art. Portrait photographs of Rapacki are preserved in the Polish National Library. His paintings also continue to be sought after by private collectors and appear regularly at auctions in Poland and internationally, handled by auction houses such as DESA Unicum in Warsaw and appearing in sales like the Aukcja Malarstwa Polskiego, confirming his enduring appeal on the art market.

Conclusion

Józef Rapacki's art offers a window onto the soul of the Polish landscape. Through his dedicated observation, technical mastery, and sensitive interpretation, he transformed ordinary scenes of forests, marshes, and fields into poetic statements. His unique blend of Realism, Symbolism, and Romanticism allowed him to convey not just the appearance of nature, but also its moods and emotional resonance. As a "poet of the Polish landscape," Rapacki created a body of work that continues to captivate viewers with its quiet beauty, technical finesse, and deep connection to the natural world of his homeland. His contribution remains a vital part of the rich tapestry of Polish art history.