Antoni Kozakiewicz (1841-1929) stands as a significant figure in 19th and early 20th-century Polish art, a painter whose canvases captured the multifaceted realities and romanticized visions of his era. A product of rigorous academic training and a keen observer of the world around him, Kozakiewicz navigated the currents of Realism, historical narrative, and ethnographic interest, leaving behind a body of work that continues to offer insights into Polish culture, societal dynamics, and the artistic preoccupations of his time. His legacy is particularly tied to his depictions of Polish peasant life, pivotal moments in national history, and, most notably, his extensive and often romanticized portrayals of the Roma people.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Born in May 1841 in Krakow, then part of the Austrian Partition of Poland, Antoni Kozakiewicz's artistic journey began in a city rich with history and cultural ferment. Krakow, despite the political subjugation, remained a spiritual and intellectual heartland for Poles, and its artistic institutions played a crucial role in nurturing national talent. Kozakiewicz enrolled in the Krakow School of Fine Arts (Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych w Krakowie), a preeminent institution that had fostered many of Poland's leading artists. He studied there diligently, likely under the influence of figures such as Władysław Łuszczkiewicz, a history painter and educator, and Wojciech Korneli Stattler, absorbing the academic principles of drawing, composition, and historical painting that were central to the curriculum. He graduated in 1868, equipped with a solid technical foundation.

Seeking to further refine his skills and broaden his artistic horizons, Kozakiewicz, like many aspiring artists from Central and Eastern Europe, looked towards the major artistic centers of the German-speaking world. He moved to Vienna, the imperial capital, to continue his studies at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien). There, he studied under Professor Eduard von Engert, a history painter of repute. Vienna's art scene, with its grand imperial collections and thriving contemporary exhibitions, would have exposed Kozakiewicz to a wider range of European artistic trends, further shaping his evolving style.

The Munich Period and the Embrace of Realism

After his Viennese sojourn, Kozakiewicz made a pivotal move that would significantly define his career: he relocated to Munich around 1871. The Bavarian capital had, by this time, become a major magnet for artists from across Europe, particularly from Poland. The Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich (Königliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste) was renowned, and a distinct "Munich School" of Polish painters emerged, characterized by its adherence to Realism, often infused with patriotic themes, genre scenes, and dramatic historical narratives.

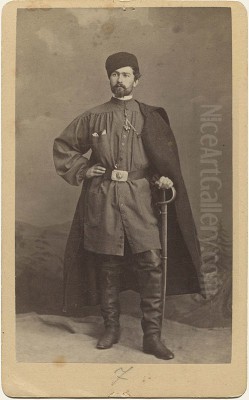

Kozakiewicz became an active participant in this vibrant artistic milieu, remaining in Munich until around 1900. Here, he would have been in the company of, or at least aware of, prominent Polish artists who also spent significant time in the city. Figures like Józef Brandt, famous for his dynamic battle scenes and depictions of Cossack life, Maksymilian Gierymski and his brother Aleksander Gierymski, both masters of Realism capturing Polish landscapes and urban scenes with poignant accuracy, and Józef Chełmoński, known for his evocative portrayals of Polish rural life and dramatic horse-drawn sleighs, were all part of this influential group. While Kozakiewicz developed his own distinct voice, the shared emphasis on realistic representation, meticulous detail, and often narrative content was a hallmark of the Munich Poles. Other notable Polish artists associated with Munich around this period or influenced by its school included Władysław Czachórski, celebrated for his refined portraits and genre scenes, and Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski, another painter of dramatic Polish historical and genre subjects.

During his nearly three decades in Munich, Kozakiewicz honed his Realist style. His paintings from this period often featured genre scenes, historical subjects, and portraits. He participated in exhibitions in Munich, Berlin, and Vienna, gaining recognition and winning medals for his work, which testified to his growing stature and the appeal of his chosen subjects and meticulous execution.

Themes in Kozakiewicz's Art

Kozakiewicz's oeuvre can be broadly categorized into several key thematic areas, each reflecting different facets of his artistic interests and the cultural context in which he worked.

Polish History and Patriotism

Living and working during a period when Poland did not exist as an independent state (having been partitioned by Russia, Prussia, and Austria in the late 18th century), themes of national history and patriotism were potent and recurrent subjects for Polish artists. These works served not only as artistic expressions but also as means of preserving national identity, commemorating past glories, and subtly (or overtly) commenting on the contemporary political situation.

Kozakiewicz contributed to this tradition. His painting Śmierć Karola Levittoux w Cytadeli Warszawskiej (The Death of Karol Levittoux in the Warsaw Citadel), created in 1868, is a poignant example. Karol Levittoux was a Polish independence activist involved in conspiracies against Russian rule who, after being arrested and tortured in the infamous Warsaw Citadel, chose to commit suicide by setting his straw mattress alight rather than betray his comrades. Kozakiewicz's depiction of this tragic event would have resonated deeply with Polish audiences, symbolizing sacrifice and resistance.

Another work, Trzy pokolenia (Three Generations), likely explored themes of continuity and the passing down of national traditions or memories of struggle across generations, a common motif in art dealing with national identity under duress. His involvement in the Polish independence movement, which reportedly led to his imprisonment during a war (possibly related to the January Uprising of 1863-64 or its aftermath, though his direct participation in the Uprising itself at age 22 would need further specific verification), underscores the personal conviction behind these historical themes. The spirit of artists like Artur Grottger, whose cycles documented the pathos of the January Uprising, or the monumental historical canvases of Jan Matejko, though Matejko was of an older generation and a towering figure in Krakow, created a powerful backdrop for historical painting in Poland.

Rural Life and Genre Scenes

Alongside historical subjects, Kozakiewicz was a keen observer and chronicler of contemporary Polish life, particularly rural and peasant life. These genre scenes were popular in 19th-century Realism across Europe, reflecting an interest in the lives of ordinary people. For Polish artists, depicting the peasantry also had national undertones, as the rural population was often seen as the repository of authentic Polish culture and traditions.

Works like Przed karczmą (In Front of the Tavern) would have captured typical scenes of village social life, the tavern being a central hub for interaction, news, and often, hardship. Do sądu (To Court) suggests a narrative scene, perhaps depicting peasants involved in a local legal dispute, offering a glimpse into the social structures and everyday dramas of the countryside. His painting CHŁOPCIE W SZAROWARACH (Boy in Baggy Trousers, or perhaps more evocatively, Boy in Traditional Peasant Trousers), dated 1890, focuses on a single figure, likely a young peasant boy, rendered with the detailed observation characteristic of Realism. Another piece, Mały geniusz (Little Genius), also from 1890, hints at a charming scene, perhaps of a precocious child, set within a rural or modest domestic context. These works align with the broader European Realist interest in everyday subjects, akin to the work of French artists like Jean-François Millet or Gustave Courbet, though Kozakiewicz’s focus remained firmly on Polish subjects.

The Enduring Fascination: Kozakiewicz and the Roma People

Perhaps the most distinctive and widely recognized aspect of Antoni Kozakiewicz's artistic output is his extensive series of paintings depicting the Roma (often referred to as Gypsies in historical contexts) people. This became a signature theme, and his works in this vein are numerous and highly sought after. The Roma, with their itinerant lifestyle, distinct cultural traditions, and perceived exoticism, were a subject of fascination for many European artists and writers throughout the 19th century.

Kozakiewicz approached this subject with a Realist's eye for detail but often imbued his scenes with a romantic sensibility. His paintings capture various aspects of Roma life: their camps, musical performances, fortune-telling, family groups, and interactions with their animals, particularly horses. Obóz cygański (Gypsy Camp), dated 1885, and Gipsy Family (Gypsy Family), 1886, are titles indicative of this focus. These works often portray the Roma in picturesque outdoor settings, emphasizing their connection to nature and their communal way of life.

One of his most famous works in this genre is Kartomantka (The Fortune Teller), painted in 1884. This piece typically depicts a Roma woman engaged in the act of divination, a subject rich with connotations of mystery and the esoteric. Kozakiewicz’s portrayal, while detailed in costume and setting, often contributed to the romanticized image of the Roma prevalent at the time. While his works provide valuable visual documentation of Roma life from a 19th-century perspective, modern scholarship often views such depictions through a critical lens, acknowledging the tendency towards exoticization and the perpetuation of stereotypes, however sympathetically intended. Nevertheless, Kozakiewicz's dedication to this subject was profound, and his paintings of the Roma are considered an important, if complex, part of his legacy. His approach can be contrasted with other artists who depicted marginalized groups, some with more ethnographic rigor, others with even greater romanticism.

Signature Works and Artistic Style

Antoni Kozakiewicz's style is firmly rooted in 19th-century Realism, with a strong emphasis on accurate drawing, detailed rendering of textures and surfaces, and carefully constructed compositions. His academic training is evident in the solidity of his figures and his command of anatomy and perspective.

In Śmierć Karola Levittoux w Cytadeli Warszawskiej (1868), one can expect a dramatic composition, likely employing chiaroscuro to heighten the tragic mood, focusing on the solitary figure of Levittoux in his prison cell. The emotional intensity of the subject would be conveyed through pose, facial expression, and the oppressive atmosphere of the Citadel.

His genre scenes, such as Przed karczmą or Do sądu, would showcase his ability to capture the nuances of everyday life, the character of individuals through their attire and posture, and the specific details of Polish rural architecture and landscapes. The color palettes in these works are generally naturalistic, reflecting the earthy tones of the countryside or the more subdued hues of interior scenes.

The Roma paintings, like Kartomantka (1884) or Obóz cygański (1885), often feature richer colors, particularly in the depiction of traditional Roma clothing. There is a careful attention to the textures of fabrics, the sheen of metal objects, and the ruggedness of the landscape. While Realist in technique, these works often possess a romantic atmosphere, achieved through the picturesque arrangements of figures, the play of light, and the evocative portrayal of the Roma lifestyle. The figures are typically individualized, yet they also serve as representatives of a distinct cultural group.

A work like Powitanie cesarza na dworcu we Lwowie (Welcoming the Emperor at the Lviv Railway Station), dated 1890, would have been a more complex undertaking, requiring the depiction of numerous figures, architectural details of the Lviv (then Lemberg, in the Austrian partition) railway station, and the pomp and ceremony of an official imperial visit. Such a painting would demonstrate his skill in handling large-scale compositions and capturing a specific historical moment with accuracy and a sense of occasion.

Contemporaries and the Polish Art World

Kozakiewicz's career spanned a dynamic period in Polish art. While in Munich, he was part of a significant expatriate Polish artistic community. Beyond those already mentioned (Brandt, the Gierymski brothers, Chełmoński), other Polish artists were making their mark. For instance, Leon Wyczółkowski, though later associated with the Young Poland movement and Impressionism, also spent time studying in Munich. Jacek Malczewski, a towering figure of Polish Symbolism, also had Munich connections in his formative years. The interactions, shared experiences, and mutual influences within the Munich Polish circle were vital for the development of Polish art.

Back in Poland, particularly in Krakow, artistic life was also vibrant. The Academy of Fine Arts continued to produce new talent. Figures like Olga Boznańska, a generation younger than Kozakiewicz, emerged as a leading portraitist with a distinctive psychological depth, influenced by Impressionism and Intimism. While Kozakiewicz was primarily a Realist, the later part of his career would have overlapped with the rise of Symbolism and the Young Poland (Młoda Polska) movement, which brought new aesthetic and philosophical concerns to the fore, championed by artists like Stanisław Wyspiański and the aforementioned Malczewski.

Kozakiewicz's participation in exhibitions in Berlin, Vienna, and Munich placed his work within a broader European context, allowing for comparison with German, Austrian, and other Central European Realist painters. His focus on specifically Polish themes, however, ensured his relevance primarily within the narrative of Polish national art.

Later Career, Recognition, and Legacy

After his long and productive period in Munich, Antoni Kozakiewicz eventually returned to Poland. He continued to paint, though information about his very late career is less prominent than his Munich period. He passed away in December 1929, at the age of 88, having lived through the final decades of Poland's partition, the turmoil of World War I, and the first decade of Poland's restored independence in 1918.

His works found their way into significant collections. The National Museum in Krakow and the National Museum in Warsaw, Poland's premier art institutions, hold examples of his paintings, attesting to his recognized place in the canon of Polish art. His paintings also appear in private collections and periodically surface at auctions, where his Roma-themed works, in particular, often command considerable interest. For instance, Gipsy Family has been noted in auction records, such as those of Abell Auction Co.

The "controversies" or critical discussions surrounding Kozakiewicz's work, as noted in some analyses, primarily revolve around his depiction of the Roma. While his paintings are valued for their artistic merit and as historical documents of a sort, contemporary perspectives often highlight the element of romanticization and the potential for perpetuating stereotypes. This is a common critique leveled at many 19th-century European artists who depicted ethnic or cultural "others." It doesn't necessarily diminish the artistic skill involved but adds a layer of critical interpretation regarding the cultural politics of representation.

His historical paintings, while perhaps less numerous or famous than those of specialists like Matejko, contributed to the visual narrative of Polish history and identity. His genre scenes offer valuable insights into the social fabric of 19th-century Poland.

Antoni Kozakiewicz remains an important figure for several reasons. He was a skilled practitioner of Realism, contributing to its development within Polish art. His long tenure in Munich connects him to a key chapter in the story of Polish artists abroad. Most significantly, his extensive body of work on the Roma people, despite the complexities of its interpretation, forms a unique and notable contribution to European art, offering a window into both the lives of his subjects and the perceptions of his time. His dedication to Polish historical and genre themes further solidifies his position as a chronicler of his nation's life and heritage. His art, therefore, continues to be studied for its technical accomplishment, its thematic content, and its reflection of the cultural and historical currents of 19th and early 20th-century Poland.