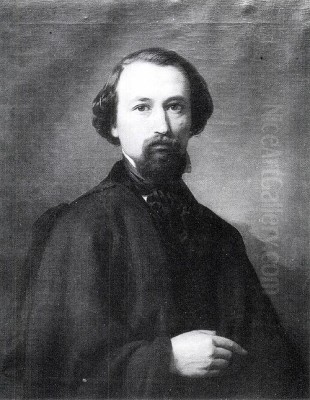

Jozsef Molnar (1821-1899) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century Hungarian art. Active during a period of burgeoning national identity and artistic development, Molnar navigated the currents of European art, blending academic precision with the burgeoning spirit of Romanticism. His contributions, particularly in the realms of historical and religious painting, as well as landscape, earned him a respected place among his contemporaries and left a lasting mark on Hungary's artistic heritage. His life spanned a transformative era, witnessing the evolution of artistic styles from Neoclassicism's wane through the height of Romanticism and the rise of Realism.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Zsámbok, Hungary, in 1821, Jozsef Molnar's artistic inclinations emerged early. His initial training took place within his homeland, likely in Pest (later part of Budapest), which was becoming an increasingly important cultural center. Like many ambitious artists of his generation seeking to refine their skills and broaden their horizons, Molnar understood the necessity of studying abroad at the major European art academies, which were considered the epicenters of artistic training and innovation at the time.

His journey led him first to the prestigious Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. Vienna, as the capital of the Habsburg Empire, was a crucible of artistic activity. There, Molnar had the invaluable opportunity to study under Leopold Kupelwieser, a prominent Austrian painter associated with the late Neoclassical and early Romantic styles, and notably connected to the Nazarene movement. This exposure to Kupelwieser's emphasis on clear lines, detailed execution, and often spiritually infused subject matter would have provided Molnar with a strong technical foundation and an appreciation for meticulous craftsmanship.

Seeking further development, Molnar continued his studies in Munich at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. Munich in the mid-19th century was another vital hub, particularly known for its school of historical painting. While specific teachers in Munich might be debated, the environment itself was steeped in the traditions of German Romanticism and the increasingly popular, often large-scale historical genre championed by figures like Karl von Piloty. This period undoubtedly exposed Molnar to different approaches to composition, colour, and thematic interpretation, further shaping his artistic vocabulary.

The Grand Tour: Travels and Influences

Following the tradition of the Grand Tour, albeit adapted to the 19th-century context, Molnar embarked on travels that were crucial to his artistic maturation. Italy, the historical cradle of Western art, was an essential destination. He spent considerable time there, immersing himself in the masterpieces of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, studying the ruins of antiquity, and absorbing the unique light and atmosphere of the Italian landscape. This experience is reflected in the numerous Italian landscapes he would paint throughout his career, capturing the picturesque beauty of the countryside and ancient sites.

His travels also extended to Switzerland. The dramatic Alpine scenery, a favoured subject for Romantic artists across Europe, clearly captivated Molnar. The sublime power of the mountains, the interplay of light and shadow on rugged peaks, and the pastoral charm of Alpine valleys offered rich material for his brush. These landscapes, alongside his Italian scenes, demonstrate his engagement with the broader European Romantic landscape tradition, echoing, if not directly influenced by, the spirit found in the works of artists like the English master J.M.W. Turner or the German Caspar David Friedrich, who sought to convey nature's emotional and spiritual resonance.

These journeys were not merely sightseeing expeditions; they were intensive periods of study and sketching. Molnar honed his observational skills, experimented with capturing different atmospheric effects, and gathered visual material that would inform his work for years to come. The direct encounter with diverse landscapes and artistic traditions enriched his palette, compositional strategies, and thematic range, moving him beyond purely academic constraints.

Hungarian Historical Painting and National Romanticism

Upon returning to Hungary, Molnar became an active participant in the nation's vibrant artistic life. The mid-to-late 19th century was a period of intense national awakening in Hungary, following the failed Revolution of 1848-49. Art, particularly historical painting, became a crucial medium for expressing national identity, celebrating heroic moments from the past, and fostering a sense of shared heritage. Artists were tasked, implicitly or explicitly, with creating a visual narrative for the nation.

Molnar contributed significantly to this genre. While perhaps not as focused on monumental historical canvases as some contemporaries like Bertalan Székely or Viktor Madarász, whose works often depicted dramatic scenes from Hungarian history with overt patriotic fervour, Molnar engaged with historical and legendary themes. His approach often combined the narrative clarity learned through his academic training with the heightened emotion and dramatic lighting characteristic of Romanticism. He joined a generation of artists, including the slightly later Gyula Benczúr, who sought to establish a distinct Hungarian school of painting, drawing on European trends but applying them to national subjects.

His religious paintings also fit within this broader cultural context. Stories from the Bible or the lives of saints, while universal, could be imbued with a specific emotional intensity and moral weight that resonated with the national mood. These works allowed Molnar to explore profound human emotions – faith, suffering, devotion, sacrifice – themes central to the Romantic sensibility.

Masterworks: Defining Canvases

Among Jozsef Molnar's most recognized works is Abraham's Journey to Canaan (Hungarian: Dezső vándorlása), painted in 1850. This significant piece, now housed in the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest, exemplifies his style during this period. The painting depicts the biblical patriarch leading his people, a subject rich with themes of faith, migration, and the search for a promised land. Stylistically, it showcases a blend of influences: the careful drawing and structured composition reflect his academic background, possibly showing lingering Nazarene ideals absorbed from Kupelwieser. However, the dramatic lighting, the emotional expressions of the figures, and the evocative landscape setting firmly place it within the sphere of Romanticism. It represents a transition, moving beyond stricter Neoclassical formulas towards a more expressive and atmospheric approach.

Another key work is The Death of St. Margaret (Szent Margit halála), completed in 1857. This painting tackles a subject from Hungarian medieval history and hagiography – Saint Margaret of Hungary, a Dominican nun known for her piety and asceticism. Such subjects allowed artists to combine religious devotion with national history. Molnar likely approached this theme with the dramatic intensity characteristic of Romantic historical painting, focusing on the emotional climax of the scene. The depiction would have aimed to evoke pathos and spiritual reflection in the viewer, using light, shadow, and expressive figures to convey the solemnity of the moment.

While these two are frequently cited, Molnar's oeuvre included a broader range of subjects. His religious works extended to other biblical scenes, such as depictions involving Abraham and Sarah, further exploring Old Testament narratives. His historical paintings drew from various periods, and his landscapes captured the beauty of Italy, Switzerland, and his native Hungary. He was also adept at genre scenes, depicting everyday life, and likely undertook portrait commissions, a common practice for artists needing to secure patronage.

Artistic Style: Bridging Tradition and Emotion

Jozsef Molnar's artistic style is best characterized as a synthesis of Academicism and Romanticism. His training in Vienna and Munich instilled in him the core tenets of academic practice: strong draughtsmanship, anatomical accuracy, balanced composition, and a relatively smooth, finished surface. This technical grounding provided a solid structure for his works, ensuring clarity and legibility, particularly important for narrative paintings. Figures like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres in France represented the pinnacle of Neoclassical and Academic precision that formed the bedrock of such training across Europe.

However, Molnar infused this academic framework with the spirit of Romanticism. This is evident in his use of colour, which often went beyond mere description to convey mood and emotion. His handling of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) frequently created dramatic effects, highlighting key figures or moments and adding emotional weight to his scenes. The emotional intensity in the expressions and gestures of his figures, the evocation of atmosphere in his landscapes, and the choice of often dramatic or poignant subject matter align him with the broader Romantic movement, exemplified by artists like Eugène Delacroix or Théodore Géricault in France.

He did not embrace the looser brushwork or revolutionary fervor of the more radical Romantics, nor did he fully transition into the Realism that gained prominence later in the century, championed by artists like Gustave Courbet. Molnar occupied a space favoured by many successful 19th-century artists: adapting Romantic sensibilities to fit within the established, respected framework of academic painting. This approach found favour with institutions and patrons, allowing him to build a successful career while still engaging with the prevailing artistic currents of his time. His work can be seen in dialogue with other European academic painters who incorporated Romantic or historical themes, such as Paul Delaroche or Jean-Léon Gérôme, though Molnar retained a distinctly Central European flavour.

Molnar and His Hungarian Contemporaries

Jozsef Molnar operated within a dynamic Hungarian art scene populated by notable talents. His career overlapped with Miklós Barabás, primarily known for his Biedermeier portraits and genre scenes, representing an earlier, more restrained style. Molnar's generation and the one immediately following included figures central to Hungarian National Romanticism and historical painting.

Bertalan Székely and Viktor Madarász were perhaps more intensely focused on large-scale, dramatic depictions of Hungarian history, often with a strong political undercurrent. Mihály Munkácsy, arguably the most internationally famous Hungarian painter of the era, achieved renown slightly later, primarily working within the vein of Realism, though his early works also showed Romantic influences. Károly Lotz, another major figure, excelled in monumental mural painting and portraiture, often displaying a refined, academic style with mythological or allegorical themes.

Compared to these contemporaries, Molnar carved out his own niche. He was perhaps less overtly nationalistic in his historical subjects than Székely or Madarász, and less committed to the gritty Realism of Munkácsy. His work often retained a lyrical quality, particularly in his landscapes, and a balanced approach in his narrative works. He shared with Lotz and Gyula Benczúr a commitment to high technical standards derived from academic training. While Pál Szinyei Merse, a contemporary of the slightly younger generation, would break new ground with his early experiments in plein-air painting and proto-Impressionist colour, Molnar remained largely within the established currents of his time. He was a respected member of the artistic community, contributing to the overall richness and development of Hungarian art during a crucial formative period.

Later Career and Lasting Legacy

Having established his reputation through his studies abroad and his significant works produced in the 1850s and beyond, Jozsef Molnar continued to be an active painter in Hungary. He settled primarily in Budapest, which by the later 19th century had firmly cemented its position as the nation's cultural and artistic capital. He likely continued to exhibit his work and participate in the institutional art life of the country.

While detailed information on his very late career or potential shifts in style might be scarce, his existing body of work secured his place in Hungarian art history. He is remembered as a skilled and versatile artist who successfully navigated the dominant artistic trends of his time. His contribution lies in his ability to synthesize the rigorous training of the academies with the expressive potential of Romanticism, applying this blend effectively to historical, religious, and landscape subjects.

Jozsef Molnar passed away in Budapest in 1899. His legacy endures through his paintings, many of which are held in the Hungarian National Gallery and other collections. He represents a key generation of Hungarian artists who, influenced by broader European movements yet deeply connected to their national context, helped shape a distinct artistic identity for Hungary in the 19th century. His work serves as a testament to the technical skill and artistic sensibilities prevalent during that era.

Conclusion: An Enduring Figure in Hungarian Art

Jozsef Molnar remains an important figure for understanding the trajectory of 19th-century Hungarian painting. As an artist trained in the major centers of Vienna and Munich, he brought a high level of technical proficiency back to his homeland. He engaged meaningfully with the dominant styles of his era, primarily Romanticism and Academicism, creating works that resonated with the cultural and national aspirations of the time. Through significant paintings like Abraham's Journey to Canaan and The Death of St. Margaret, as well as his evocative landscapes, Molnar demonstrated his ability to handle diverse themes with skill and sensitivity. He stands alongside other key Hungarian artists like Károly Lotz, Bertalan Székely, and Mihály Munkácsy, as one of the defining painters of a transformative century in Hungarian art history, leaving behind a body of work that continues to be appreciated for its craftsmanship and its reflection of a pivotal era.