Mihály Kovács (1818–1892) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of 19th-century Hungarian art. His career unfolded during a period of profound national awakening, political upheaval, and cultural flourishing in Hungary, and his oeuvre reflects the artistic currents and societal concerns of his time. Primarily known for his historical paintings, portraits, and genre scenes, Kovács navigated the stylistic realms of late Classicism, Romanticism, and the Biedermeier sensibility, creating a body of work that offers valuable insights into the artistic and cultural milieu of Hungary before the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 and in the decades that followed. His dedication to his craft and his engagement with themes central to Hungarian identity secure his place in the annals of the nation's art history.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Abádszalók, a small town in the Great Hungarian Plain, in 1818, Mihály Kovács's early life was set against the backdrop of a predominantly agrarian society, yet one increasingly stirred by Enlightenment ideals and a burgeoning sense of national consciousness. The precise details of his earliest artistic inclinations are not extensively documented, but it is clear that he demonstrated a talent for drawing and painting from a young age. This talent would eventually lead him away from his provincial origins to the artistic centers where he could receive formal training.

His journey as an artist began in earnest when he moved to Pest (later part of Budapest) to pursue his studies. Pest, at this time, was rapidly developing into the political, economic, and cultural heart of Hungary. Here, Kovács would have been exposed to the prevailing artistic trends and the works of established local artists. The artistic environment in Pest was still developing its own distinct Hungarian voice, often looking towards Vienna for academic standards and stylistic inspiration. It was in this atmosphere that Kovács honed his foundational skills, likely under the tutelage of local masters whose names might not resonate as strongly today but who played a crucial role in nurturing the next generation of Hungarian artists.

Viennese Training and Influences

Recognizing the need for more advanced instruction, Kovács, like many aspiring artists from Central Europe, made his way to Vienna, the imperial capital and a major artistic hub. He enrolled at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts Vienna (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien). This institution was a bastion of academic tradition, emphasizing rigorous training in drawing, anatomy, perspective, and the study of Old Masters. During his time in Vienna, Kovács would have been immersed in an environment rich with artistic stimuli, from the imperial collections to contemporary exhibitions.

At the Viennese Academy, he studied under influential figures. While specific records of all his tutors might be elusive, prominent professors of that era included Leopold Kupelwieser, known for his religious and historical paintings, and later, Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, a leading figure of Austrian Biedermeier painting, celebrated for his realistic portraits, genre scenes, and landscapes. The meticulous detail, emphasis on verisimilitude, and often sentimental or anecdotal subject matter characteristic of Biedermeier art, as championed by Waldmüller, undoubtedly left an impression on Kovács. Similarly, the academic tradition of historical painting, with its grand narratives and moralizing themes, would have been a core component of his education. The Viennese experience was crucial in shaping Kovács's technical proficiency and broadening his artistic horizons.

Return to Hungary and Early Career

Upon completing his studies in Vienna, Mihály Kovács returned to Hungary, equipped with a solid academic foundation and a developing artistic vision. He established himself primarily in Pest, where he began to build his career as a professional painter. The 1840s, the period of his return, was a time of intense political and cultural ferment in Hungary, often referred to as the Reform Era. This era was characterized by a strong push for liberal reforms, greater national autonomy within the Habsburg Empire, and a flourishing of Hungarian language and culture. Artists played a role in this national awakening, often depicting scenes from Hungarian history or celebrating national figures and traditions.

Kovács found a receptive audience for his skills. He undertook commissions for portraits, which were a staple for artists of the period, providing a steady source of income. His ability to capture a likeness, combined with his academic training, made him a sought-after portraitist. Alongside portraiture, he began to explore historical themes, drawing inspiration from Hungary's rich and often turbulent past. These historical compositions resonated with the patriotic sentiments of the era. His early works from this period likely demonstrated a blend of the academic precision learned in Vienna with an emerging Romantic sensibility, characterized by a greater emphasis on emotion and drama. He participated in local exhibitions, gradually gaining recognition within the Hungarian artistic community.

The Impact of the 1848-1849 Revolution

The Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence of 1848-1849 was a watershed moment in Hungarian history and had a profound impact on all aspects of society, including the arts. While Kovács's direct involvement in the revolutionary events is not extensively detailed, the spirit of the revolution and its aftermath undoubtedly influenced the thematic concerns and emotional tenor of Hungarian art for decades to come. The struggle for independence, though ultimately unsuccessful, fueled a powerful sense of national identity and provided a rich source of heroic and tragic narratives for artists.

In the years following the suppression of the revolution, during a period of Habsburg absolutism, overt expressions of nationalism were often curtailed. However, artists found ways to subtly evoke national themes through historical allegories, depictions of folk life, or portraits of historical figures. Kovács, like his contemporaries, would have navigated this complex political landscape. The demand for art that celebrated Hungarian heritage and resilience likely continued, perhaps even intensified, as a form of cultural resistance or remembrance. This period may have seen Kovács further refine his approach to historical painting, imbuing his works with a sense of pathos or quiet heroism.

Artistic Style: A Blend of Romanticism and Biedermeier

Mihály Kovács's artistic style is best understood as a synthesis of several prevailing currents of the 19th century, primarily Romanticism and the Biedermeier sensibility, all underpinned by a solid academic training. His work does not always fit neatly into a single category, often exhibiting characteristics of both.

The Romantic influence in Kovács's art is evident in his choice of historical subjects, often depicting dramatic or emotionally charged moments from Hungary's past. There is a clear desire to evoke a sense of national pride and to connect with the viewer on an emotional level. This aligns with the broader European Romantic movement's emphasis on individualism, emotion, and the glorification of the past. Artists like the French master Eugène Delacroix, with his vibrant historical canvases, or the German Romantic painters such as Caspar David Friedrich, who explored sublime landscapes and introspection, represent the broader international context of Romanticism, though Kovács's expression was more rooted in narrative history.

Simultaneously, many of Kovács's works, particularly his portraits and genre scenes, exhibit strong Biedermeier characteristics. The Biedermeier style, prevalent in German-speaking lands and Central Europe from roughly 1815 to 1848, emphasized domesticity, realism, meticulous detail, and a focus on the everyday life of the burgeoning middle class. In portraiture, this translated into a desire for accurate likenesses, often with a focus on the sitter's character and social standing, rendered with smooth brushwork and careful attention to costume and setting. Kovács's portraits often display this Biedermeier concern for verisimilitude and intimate portrayal. His genre scenes, depicting everyday life or charming anecdotes, also align with the Biedermeier appreciation for the simple, the sentimental, and the picturesque. The Austrian painter Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller is a key exemplar of this style, and his influence on Kovács is palpable.

His academic training provided the technical foundation for both these stylistic tendencies. Strong draughtsmanship, balanced compositions, and a skilled handling of anatomy and perspective are evident in his work. His color palette could vary, sometimes employing the richer, more dramatic tones associated with Romantic historical painting, and at other times adopting the clearer, more subdued colors typical of Biedermeier realism.

Representative Works

Identifying a definitive list of Mihály Kovács's most famous works can be challenging, as some may reside in private collections or have received less international exposure than those of his more widely celebrated contemporaries. However, based on available art historical records and museum collections, several paintings are frequently attributed to him and are indicative of his style and thematic concerns.

One of his notable historical paintings is The Palatine Garay Defends His King, Ladislaus V. This work exemplifies his engagement with Hungarian history, depicting a dramatic moment of loyalty and conflict. Such paintings were crucial in constructing a visual narrative of the nation's past for a 19th-century audience. The composition, character portrayal, and historical detail would have been paramount in such a piece.

Another significant work often cited is The Mourning of László Hunyadi. The story of László Hunyadi, a 15th-century Hungarian nobleman unjustly executed, was a potent national symbol of martyrdom and injustice, frequently depicted by Hungarian Romantic artists. Kovács's rendition would have aimed to capture the pathos and tragedy of the event, appealing to the patriotic and emotional sensibilities of his viewers. Viktor Madarász, a contemporary, also famously painted this subject, offering a point of comparison in terms of Romantic historical interpretation.

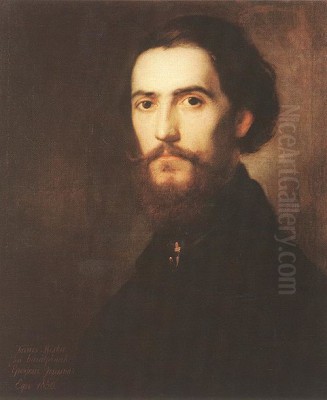

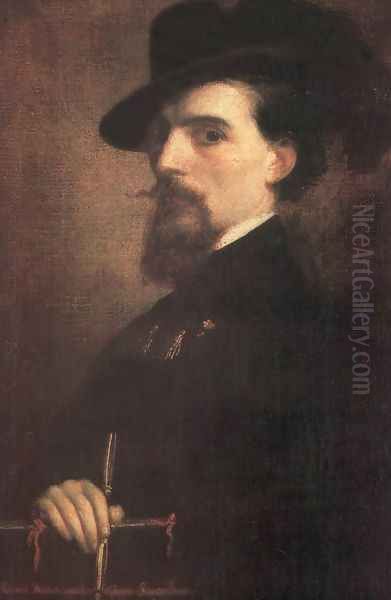

In the realm of portraiture, Kovács produced numerous works. While specific titles might vary, works such as Portrait of a Woman in Hungarian Dress or Self-Portrait (if extant and verified) would showcase his skill in capturing likenesses and conveying personality, often with the detailed realism characteristic of the Biedermeier style. These portraits also serve as valuable historical documents, recording the appearance and attire of individuals from the period. Miklós Barabás, a leading Hungarian portraitist of the era, set a high standard in this genre, and Kovács's work can be seen within this tradition.

Kovács also painted genre scenes, which depicted everyday life, often with a sentimental or anecdotal quality. A piece like The Letter Writer or similar scenes of domestic interiors or rural life would fall into this category. These works reflect the Biedermeier appreciation for the intimate and the ordinary, providing charming glimpses into the social customs of the time. Károly Kisfaludy, an earlier figure, had helped popularize genre painting in Hungary.

It is important to note that the accessibility and documentation of works by artists like Kovács can evolve as research continues and collections are digitized. The Hungarian National Gallery and other regional museums in Hungary are the primary repositories for his works and for those of his contemporaries.

Contemporaries and the Hungarian Art Scene

Mihály Kovács worked during a vibrant period in Hungarian art, alongside a generation of talented painters who collectively shaped the nation's artistic identity. Understanding his work requires placing it in context with these contemporaries.

Miklós Barabás (1810–1898) was arguably the most celebrated Hungarian painter of the mid-19th century, particularly renowned for his elegant and insightful portraits of the aristocracy and prominent cultural figures. His style, often characterized by a refined Biedermeier sensibility, set a benchmark for portraiture.

Károly Lotz (1833–1904), though slightly younger, became a dominant figure in the latter half of the century, known for his monumental frescoes, mythological scenes, and sensuous nudes. His academic style, influenced by Venetian colorism, represented a more sensuous and decorative trend.

Bertalan Székely (1835–1910) and Viktor Madarász (1830–1917) were leading exponents of Hungarian Romantic historical painting. Székely's works, such as The Discovery of the Body of Louis II, are known for their dramatic intensity and psychological depth. Madarász, who spent much of his career in Paris, also created iconic historical compositions like The Mourning of László Hunyadi, often imbued with a strong sense of national tragedy.

Gyula Benczúr (1844–1920), emerging towards the later part of Kovács's career, became a master of grand historical tableaux and opulent portraits, working in a highly polished academic style influenced by Karl von Piloty in Munich. His works, such as The Recapture of Buda Castle in 1686, represent the pinnacle of late 19th-century Hungarian historical painting.

Mór Than (1828–1899) was another significant historical and portrait painter, often collaborating with Lotz on decorative projects. His style combined academic precision with Romantic feeling.

Károly Markó the Elder (1791–1860), though spending much of his career in Italy, was highly influential as a landscape painter. His idealized, classical landscapes were admired throughout Europe and inspired a generation of Hungarian artists.

Beyond Hungary, the broader European art scene was rich with influential figures. In Vienna, besides Waldmüller, artists like Hans Makart (1840-1884) later ushered in an era of opulent historicism. In Munich, Karl von Piloty (1826-1886) was a key teacher for many Central European historical painters. In Paris, the legacy of Romantic painters like Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) and Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) continued to resonate, while the Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875) and Jean-François Millet (1814-1875) were pioneering new approaches to landscape and peasant genre scenes, paving the way for Realism. While Kovács may not have had direct contact with all these international figures, their work formed the broader artistic currents of the century.

Kovács's interactions with these Hungarian contemporaries would have occurred through exhibitions, artistic societies, and shared cultural circles in Pest-Buda. They collectively contributed to a burgeoning national art scene, each with their individual strengths and stylistic nuances, but united by a desire to create art that was both technically accomplished and meaningful for their nation.

Connection to Hungarian Art Movements

Mihály Kovács's career is intrinsically linked to the development of 19th-century Hungarian art, particularly the currents of National Romanticism and the Biedermeier style as it manifested in Hungary. He was not a radical innovator who broke entirely new ground, but rather a skilled practitioner who absorbed and synthesized the prevailing artistic trends of his time, adapting them to Hungarian themes and sensibilities.

His historical paintings align closely with the aims of National Romanticism, an artistic and literary movement that sought to define and celebrate national identity through the depiction of historical events, legends, and folk traditions. In a Hungary striving for greater autonomy and self-definition, art that glorified the nation's past heroes, struggles, and cultural heritage played a vital role. Kovács contributed to this visual construction of national identity, alongside artists like Székely and Madarász, though perhaps with a less overtly dramatic or tragic tone than some of his peers. His works provided accessible and relatable images of Hungarian history for a growing middle-class audience.

The Biedermeier influence in his work connected him to a broader Central European cultural phenomenon. In Hungary, the Biedermeier style found expression in portraiture, genre painting, and the decorative arts, reflecting the values of domesticity, order, and sentimentalism cherished by the urban bourgeoisie. Kovács's portraits, with their emphasis on realistic likeness and often intimate portrayal, and his charming genre scenes, fit well within this Biedermeier framework. He helped to popularize these forms of art in Hungary, catering to the tastes of a clientele that appreciated craftsmanship and relatable subject matter.

He was part of a generation that laid the groundwork for the institutionalization of art in Hungary, including the establishment of art societies and public exhibitions. While he may not have been a leading figure in art theory or pedagogy in the same way as some later artists, his consistent production and participation in the artistic life of Pest-Buda contributed to the growing vibrancy and professionalism of the Hungarian art world. His work represents a crucial phase in the evolution of Hungarian painting, bridging the gap between earlier, more classically inclined artists and the later, more diverse styles that emerged towards the end of the 19th century.

Later Years and Legacy

Mihály Kovács continued to paint throughout the latter half of the 19th century. This period saw significant changes in Hungary, particularly after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, which granted Hungary greater autonomy and ushered in an era of rapid modernization and economic development, known as the "Belle Époque" of Budapest. The art world also evolved, with new influences from Paris and Munich becoming more prominent, and new generations of artists exploring styles such as Realism, Naturalism, and eventually Impressionism and Art Nouveau.

It is likely that Kovács remained largely faithful to the stylistic approaches he had developed earlier in his career, rooted in academicism, Romanticism, and Biedermeier realism. While younger artists might have embraced more avant-garde trends, there would have remained a demand for the types of well-crafted historical paintings, portraits, and genre scenes that Kovács produced. He may have taken on students or played a role in local art organizations, though detailed records of his later teaching activities are not as prominent as those of some of his contemporaries who held formal academic positions.

Mihály Kovács passed away in 1892. By the time of his death, the Hungarian art scene was on the cusp of major transformations, with artists like Simon Hollósy and the Nagybánya artists' colony soon to introduce plein-air painting and more modern sensibilities.

Kovács's legacy lies in his contribution to the richness and diversity of 19th-century Hungarian art. He was a skilled and diligent painter who effectively captured the spirit of his time, particularly the national aspirations and the Biedermeier cultural values prevalent in mid-century Hungary. His works serve as valuable historical and cultural documents, offering insights into the society, personalities, and historical consciousness of the era. While he may not be as internationally renowned as some other European masters of the 19th century, or even as some of his more dramatically inclined Hungarian contemporaries, his paintings hold an important place in the collections of the Hungarian National Gallery and other Hungarian museums. He is remembered as a competent and respected artist who played his part in the development of a distinct national art tradition in Hungary, a tradition that continued to evolve and flourish in the decades following his death. His art provides a window into a pivotal period of Hungarian history, reflecting both its grand historical narratives and its more intimate, everyday realities.