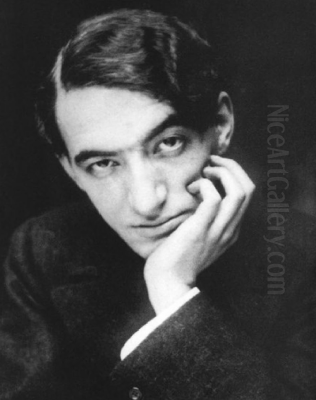

Jules Pascin, born Julius Mordecai Pincas, stands as a unique and poignant figure within the vibrant tapestry of the early 20th-century School of Paris. A Bulgarian-born artist who later became an American citizen, Pascin is celebrated primarily for his sensitive, intimate, and often melancholic depictions of women. His life, marked by restless travel, bohemian excess, and profound inner turmoil, mirrored the intoxicating yet fragile atmosphere of Montparnasse, the Parisian district he came to embody. Though sometimes overshadowed by the titans of modernism with whom he associated, Pascin cultivated a distinctive artistic voice, characterized by delicate draftsmanship, ethereal color palettes, and a deep empathy for his subjects, leaving behind a body of work that continues to captivate with its quiet intensity and psychological depth. His journey through the art capitals of Europe and America, his complex social interactions, and his tragic end contribute to the enduring mystique of an artist forever linked with the ephemeral world he portrayed.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Jules Pascin was born on March 31, 1885, in Vidin, Bulgaria, into a prosperous Sephardic Jewish family involved in the grain trade. His early life was marked by a burgeoning artistic talent and a rebellious spirit that clashed with his family's bourgeois expectations. Seeking formal art training, he left Bulgaria, receiving initial artistic encouragement in Bucharest before moving on to the major art centers of Vienna and Munich. In Munich, around 1903-1905, his exceptional drawing skills quickly gained attention. He began contributing satirical drawings and illustrations to the renowned German magazine Simplicissimus, a publication known for its sharp wit and avant-garde aesthetics. This early success provided him not only with financial independence but also connected him with the burgeoning modernist movements in Germany. During this period, he encountered influential figures like Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and Albert Weisgerber, absorbing the currents of Expressionism and Symbolism that were animating the Central European art scene. However, the magnetic pull of Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world, proved irresistible.

Paris and the Montparnasse Milieu

Around 1905, Pascin arrived in Paris, drawn by the city's unparalleled artistic energy. He initially settled in Montmartre, renting a studio and quickly immersing himself in the bohemian circles that defined the era. He soon gravitated towards Montparnasse, which was rapidly becoming the new epicenter of artistic life. Pascin, with his charm, generosity, and penchant for hosting lavish gatherings, became a central figure in this milieu, earning the affectionate nickname "Prince of Montparnasse." His studio became a legendary meeting place, attracting a diverse crowd of artists, writers, models, and intellectuals. He formed close friendships and associations with many leading figures of the School of Paris, including Amedeo Modigliani, whose sensitive portraits share some affinities with Pascin's work, as well as Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Chaïm Soutine, and Moïse Kisling. His social life was as much a part of his identity as his art, characterized by legendary parties fueled by alcohol and conversation that often lasted until dawn. This vibrant, if tumultuous, environment provided both the inspiration and the backdrop for much of his artistic output.

Artistic Style and Signature Themes

Pascin's artistic style is difficult to categorize neatly, as it synthesized elements from various modernist movements while retaining a highly personal character. Early influences included the sinuous lines of Art Nouveau, visible in his graphic work, and the structural concerns of Paul Cézanne. As he matured, his work absorbed aspects of Fauvism in its expressive use of color, Cubism in its subtle fragmentation of form, and Expressionism in its emotional intensity. However, Pascin never fully committed to any single doctrine, instead forging a unique style centered on his exceptional draftsmanship. His signature technique involved delicate, flickering lines, often drawn directly onto the canvas or paper, combined with thin, translucent layers of oil paint or watercolor. This created a distinctive pearly, opalescent quality, lending his figures an ethereal, almost dreamlike presence. His color palette was typically soft and muted, dominated by grays, pinks, ochres, and pale blues, contributing to the intimate and often melancholic mood of his works.

The overwhelming focus of Pascin's art was the female figure. He specialized in intimate portrayals of women, often models, dancers, or prostitutes, captured in moments of repose, contemplation, or quiet vulnerability. His nudes and semi-nudes are rarely idealized; instead, they possess a palpable sense of lived experience, weariness, and introspection. He depicted his subjects in natural, unposed attitudes – lounging on beds, seated in chairs, lost in thought. There is a profound empathy in his gaze, a sense of shared humanity that transcends mere observation. While sometimes tinged with eroticism, his works primarily explore themes of intimacy, solitude, and the fleeting nature of beauty and youth. He worked proficiently across mediums, producing a vast number of drawings, watercolors, etchings, and oil paintings, all marked by his characteristic sensitivity and linear grace. His scenes of Parisian life, capturing the atmosphere of cafes and streets, also form an important part of his oeuvre, reflecting his keen observation of his surroundings.

Representative Works

Pascin's body of work includes numerous paintings, drawings, and prints that exemplify his unique style and thematic concerns. While a comprehensive list is extensive, several works stand out as representative of his artistic achievements. Bavardage (Chatter or Gossip), an oil painting from 1923-1924, showcases his ability to capture intimate group dynamics, likely depicting women in a relaxed, perhaps domestic or brothel setting, rendered with his typical soft focus and delicate line work. Works like Nu étendus les jambes croisées (Reclining Nude with Crossed Legs), executed in crayon and watercolor, highlight his mastery of the female form in repose, emphasizing vulnerability and introspection through subtle posture and expression. Similarly, Two Women Allongé (Two Reclining Women), in watercolor and ink, demonstrates his fluid draftsmanship and his interest in the quiet interactions or shared solitude between figures.

His earlier works, such as Man with a Hat (1906), reveal his graphic sensibility, while paintings like In the Park (1913) show his engagement with Impressionist themes of modern life, albeit rendered with his developing personal touch. Coquetterie (Coquetry), blending oil and ink, likely captures a moment of playful or perhaps performative femininity. The watercolor and pencil work Kérukhnú hő nő (Woman in Blue Dress) exemplifies his skill in combining mediums to achieve nuanced tonal effects and psychological depth. Beyond paintings and drawings, Pascin was also an accomplished printmaker, as seen in his 1929 etching series illustrating Cinderella, where his linear style found a perfect outlet. These works, varying in medium and scale, consistently reflect Pascin's preoccupation with the inner lives of his subjects, rendered with his signature blend of tenderness and melancholy.

The American Interlude

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 prompted Pascin, a Bulgarian citizen (Bulgaria eventually joined the Central Powers), to leave France. He traveled to London and then sailed for the United States, arriving in October 1914. He spent the war years primarily in New York City, but also traveled extensively, particularly to the American South (Charleston, New Orleans) and to Cuba. During his time in America, he continued to paint and draw, absorbing the different atmosphere and light of the New World. His work from this period sometimes reflects his new surroundings, depicting street scenes and local characters with the same keen eye he applied to Paris. He exhibited his work in the United States, notably participating in group shows and gaining some recognition, building upon the exposure his work had received at the groundbreaking Armory Show in New York in 1913, which had introduced European modernism to American audiences on a large scale. In 1920, Pascin became a naturalized American citizen. Despite achieving citizenship and a degree of success, he reportedly felt somewhat alienated from the American cultural scene and longed for the familiar bohemian milieu of Paris. Shortly after the war ended and travel became easier, he made the decision to return to France, the city that remained his spiritual home.

A Life of Contradictions: Fame, Festivity, and Inner Turmoil

Pascin's life in Paris, both before and after his American sojourn, was marked by stark contradictions. Outwardly, he cultivated the image of the bon vivant, the "Prince of Montparnasse," known for his generosity, his ever-present bowler hat, and his legendary studio parties where champagne and whiskey flowed freely. Anecdotes abound regarding his prodigious capacity for alcohol and his role as a charismatic, if sometimes enigmatic, host. He moved easily among the artistic elite, counting figures like Ernest Hemingway among his acquaintances (Hemingway would later memorably portray him in A Moveable Feast). His studio was a hub of creative energy and social interaction, a microcosm of the vibrant, experimental spirit of Montparnasse in the 1920s. His artistic reputation grew steadily, with successful exhibitions in Paris and internationally, and his works were sought after by collectors.

Beneath this convivial exterior, however, Pascin wrestled with profound inner demons. He suffered from chronic depression and debilitating alcoholism, struggles that became increasingly apparent over time. His personality was described as complex and sometimes difficult; contemporaries noted a "feigned candor," a way of interacting that could seem open yet ultimately kept others at a distance. There were flashes of temper, as suggested by an anecdote involving a sharp retort to Chaïm Soutine's criticism of one of his models. This tension between his public persona as a celebrated artist and socialite and his private battles with addiction and despair created a volatile existence. He seemed driven by a restless energy, constantly working yet perhaps never fully satisfied, caught between the demands of his art and the destructive patterns of his lifestyle. This internal conflict would ultimately prove insurmountable.

The Tragic End

The final chapter of Jules Pascin's life unfolded tragically in the spring of 1930. Despite his ongoing struggles, he was preparing for a prestigious solo exhibition at the Galerie Georges Petit, an event that should have marked a high point in his career. However, the weight of his depression and alcoholism had become unbearable. On June 2, 1930, just days before the exhibition was scheduled to open, Pascin took his own life in his Montparnasse studio at the age of 45. The circumstances were particularly grim: he first slit his wrists, and when death did not come quickly enough, he hanged himself from the studio doorknob. Before dying, he scrawled a final message in blood on the wall, addressed to his lover, Lucy Krohg (though he was legally married to the painter Hermine David). His body was discovered several days later by friends concerned about his absence.

News of Pascin's suicide sent shockwaves through the Parisian art world. His funeral was a major event, attended by throngs of artists, writers, critics, and admirers. In a remarkable display of respect and mourning, gallery owners across Paris closed their establishments for the duration of the funeral procession. The reasons cited for his suicide centered on his long battle with depression and alcohol, perhaps compounded by anxieties about his career, financial worries, or a deeper existential despair stemming from the very bohemian lifestyle he had come to symbolize. His death marked the end of a unique artistic talent and served as a somber reminder of the personal costs that sometimes accompanied the creative ferment of the era.

Legacy and Influence

Jules Pascin occupies a distinct and enduring place in the history of 20th-century art. While perhaps not as revolutionary as Picasso or Matisse, he was a master draftsman and a colorist of exceptional subtlety, creating a body of work characterized by its intimate mood and psychological acuity. He remains inextricably linked with the School of Paris and the vibrant, ephemeral world of Montparnasse in its heyday. His primary contribution lies in his sensitive and empathetic portrayal of women, capturing fleeting moments of vulnerability, introspection, and quiet sensuality with a unique blend of tenderness and melancholy. His signature style, with its delicate, nervous line and pearly, translucent color, is instantly recognizable.

Although his direct influence on subsequent generations of artists may be less pronounced than that of some of his contemporaries, his work continues to be admired for its technical skill and emotional resonance. He demonstrated how modernist sensibilities could be applied to intimate, figurative subjects, offering an alternative to grander abstract or narrative modes. His works are held in major museum collections around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, ensuring his visibility to contemporary audiences. Pascin's life and art, marked by both brilliance and tragedy, serve as a compelling testament to the complexities of the creative spirit navigating the exhilarating and often perilous currents of modern life. He remains the "Prince of Montparnasse," forever capturing the fragile beauty and underlying sadness of the world he inhabited.