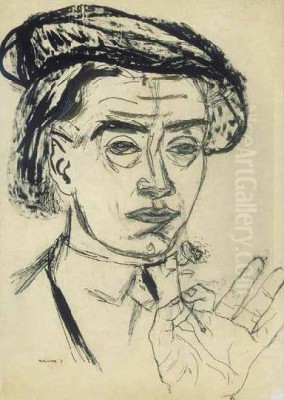

Imre Ámos stands as one of Hungary's most poignant artistic figures of the 20th century, a painter whose life and work were tragically intertwined with the cataclysmic events of his time. A Hungarian Jewish artist, his oeuvre is a testament to a profound spirituality, a deep connection to his heritage, and an unflinching gaze into the abyss of human suffering. His art, often described as a form of "associative expressionism," masterfully blended Jewish mysticism, folk traditions, and the haunting premonitions of a world on the brink of collapse.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born Ungár Imre on December 7, 1907, in Nagykálló, a town in eastern Hungary with a significant Hasidic Jewish community, his early environment undoubtedly shaped his spiritual and artistic inclinations. The rich tapestry of Jewish traditions, rituals, and storytelling he witnessed in Nagykálló would later become a foundational element in his visual language. This upbringing instilled in him a deep reverence for the mystical and the symbolic, themes that would permeate his mature work.

His formal artistic education began after initial studies at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics. He then enrolled at the Royal Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest, where he studied under Gyula Rudnay. Rudnay, known for his romantic, somewhat traditional style, provided Ámos with a solid technical grounding. However, Ámos's artistic spirit was restless, seeking a more personal and modern mode of expression. Early influences also included the post-impressionistic sensibilities of Hungarian masters like József Rippl-Rónai and the more avant-garde explorations of Róbert Berény, a key figure in the "Nyolcak" (The Eight) group.

In 1931, Ámos began to exhibit his works, signaling his entry into the Hungarian art scene. A significant personal and artistic milestone occurred in 1934 when he became a member of KÚT (Képzőművészek Új Társasága, or New Society of Artists). This association placed him among progressive artists seeking new forms of expression beyond academic constraints. It was also around this period, in 1937, that he officially changed his surname from Ungár to Ámos, a deliberate choice to honor the biblical prophet Amos, known for his calls for social justice and his powerful, often somber, prophecies. This act itself was a statement, reflecting his growing concern with moral and spiritual themes.

The Parisian Encounter and the Influence of Chagall

A pivotal moment in Imre Ámos's artistic development was his visit to Paris in 1937. The French capital was then the undisputed center of the art world, a vibrant hub of modernist experimentation. During this trip, Ámos, accompanied by another Hungarian artist (likely his close friend and contemporary Lajos Vajda, who shared similar artistic quests), had the opportunity to meet Marc Chagall.

Chagall, himself a Jewish artist hailing from Eastern Europe, had already achieved international renown for his dreamlike, symbolic paintings that drew heavily on Jewish folklore and personal memory. The encounter with Chagall and the exposure to his work had a profound and lasting impact on Ámos. He saw in Chagall a validation of his own desire to integrate Jewish themes and a deeply personal, almost mystical vision into a modern artistic language. Chagall's floating figures, his poetic use of color, and his ability to weave narrative and symbol into a cohesive whole resonated deeply with Ámos.

While Ámos never simply imitated Chagall, the influence is discernible in his increasingly symbolic imagery, his lyrical compositions, and his exploration of themes related to Jewish life and spirituality. However, Ámos's art would increasingly carry a darker, more tragic undertone, reflecting the ominous political climate in Europe and his own premonitions of impending disaster. This distinguished his work from the often more whimsical, albeit sometimes melancholic, world of Chagall. Other artists whose work he would have encountered in Paris, such as members of the Surrealist movement like Max Ernst or Salvador Dalí, or the poetic intimacy of Paul Klee, may also have contributed to the broadening of his artistic horizons, encouraging a move towards more symbolic and less literal representation.

Szentendre: An Artistic Haven and Creative Crucible

Upon his return to Hungary, Ámos, along with his wife, the equally talented painter Margit Anna, became associated with the artists' colony in Szentendre. This picturesque town on the Danube Bend, north of Budapest, had become a magnet for artists seeking an alternative to the urban environment of the capital. Artists like Károly Ferenczy had earlier established its reputation, and by the 1930s, a new generation, including Ámos, Lajos Vajda, Dezső Korniss, and Endre Bálint, were forging a unique artistic identity there.

The Szentendre artists were interested in synthesizing Hungarian folk art traditions, Orthodox Christian iconography (prevalent in the town's Serbian churches), and modern European artistic trends, particularly Surrealism and Constructivism. For Ámos, Szentendre provided a supportive environment where he could further develop his personal style. His work from this period often features motifs drawn from the local landscape and its spiritual atmosphere, interwoven with his increasingly personal symbolism.

His collaboration and artistic dialogue with Margit Anna were also crucial. They married in 1935, and their relationship was one of deep mutual understanding and artistic support. Margit Anna's own work, characterized by a naive, puppet-like figuration and often unsettling, surreal narratives, complemented and sometimes contrasted with Ámos's more lyrical, though increasingly somber, style. Their shared life in Szentendre was a period of intense creativity, though shadowed by the growing threat of fascism and antisemitism in Hungary. Other artists active in Hungary at the time, such as the socially critical Gyula Derkovits or the expressive István Farkas (another Jewish painter whose work conveyed a sense of foreboding), formed part of the broader artistic landscape against which Ámos's unique voice emerged.

Themes, Symbolism, and Signature Style

Imre Ámos's art is rich in symbolism, drawing from a deep well of Jewish tradition, biblical narratives, personal dreams, and the anxieties of his era. His style, often termed "associative expressionism," allowed him to connect disparate images and ideas in a poetic, dreamlike manner.

Common motifs in his work include angels, often depicted as melancholic or ominous figures, serving as messengers between the earthly and heavenly realms, or perhaps as witnesses to human suffering. The rooster, a recurring symbol in both Jewish and Christian iconography (and notably in Chagall's work), appears frequently, sometimes heralding a new dawn, at other times perhaps a warning or a sacrificial emblem. Ladders, reminiscent of Jacob's Ladder, signify a connection to the divine, a yearning for transcendence, or an escape from earthly tribulations.

Candles and burning lights are ubiquitous, symbolizing faith, memory, the fragility of life, and the enduring light of the spirit amidst darkness. He often depicted scenes from Jewish life – festivals, rituals, and domestic interiors – imbuing them with a sense of sanctity and quiet dignity, but also an underlying vulnerability. His figures are often elongated, ethereal, and imbued with a gentle sorrow. His color palette, while capable of moments of lyrical beauty, increasingly adopted more somber tones – deep blues, grays, and earthy browns – reflecting the encroaching darkness of the times.

His approach was not merely illustrative; rather, he used these symbols to evoke emotions and explore complex spiritual and existential questions. His work often possesses a narrative quality, but the stories are rarely straightforward, inviting viewers to engage with the images on a more intuitive, emotional level. This blend of the personal, the traditional, and the universally human gives his art its enduring power.

Representative Works: Jewish Holidays and the Apocalypse Series

Among Imre Ámos's most significant contributions are his series of woodcuts titled Jewish Holidays (Zsidó ünnepek). Created in the late 1930s and early 1940s, this series captures the essence of various Jewish festivals – Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot, Hanukkah, Passover. These are not merely documentary depictions; Ámos infuses each scene with a profound spiritual atmosphere and a sense of timeless tradition. The woodcut medium, with its stark contrasts and expressive lines, lent itself well to his increasingly urgent and poignant style. These works were recognized for their artistic merit and cultural significance, with the Hungarian Jewish Museum acquiring a set and even producing them as postcards. They stand as a testament to his deep connection to his heritage and his desire to preserve its beauty and meaning in the face of growing threats.

As the political situation in Europe deteriorated and the persecution of Jews intensified, Ámos's work took on an increasingly tragic and apocalyptic tone. This culminated in his powerful Apocalypse series (Apokalipszis), created in the final years of his life, around 1944. These drawings and paintings are harrowing visions of war, destruction, and suffering, directly reflecting the horrors of the Holocaust. Drawing on both Jewish and Christian apocalyptic imagery, Ámos depicted a world consumed by fire and chaos, yet even in these darkest works, there is often a glimmer of spiritual resilience, a sense of bearing witness. These late works are raw, immediate, and deeply moving, representing the cry of a soul engulfed by an unimaginable catastrophe. The Szoskornap Notebook (Szászkér Notebook), a collection of drawings and writings from his time in forced labor, provides an intimate and heartbreaking glimpse into his final artistic expressions under duress.

The Darkening Years: Forced Labor and Tragic End

The rise of fascism in Hungary and the implementation of anti-Jewish laws had a devastating impact on Imre Ámos's life and career. From 1940 onwards, he was repeatedly conscripted into forced labor battalions, a common fate for Jewish men in Hungary during World War II. These experiences were brutal, separating him from his wife and his art, and exposing him to unimaginable hardship and cruelty.

Despite the horrific conditions, Ámos continued to draw and paint whenever possible, using art as a means of survival, a way to process his experiences, and a testament to the enduring power of the human spirit. His works from this period, often small-scale drawings created with whatever materials he could find, are imbued with an almost unbearable poignancy. They depict the suffering of his fellow laborers, the desolation of the landscapes, and his own inner turmoil and longing for solace. Painting and drawing became his sole means of artistic expression, a lifeline in a world devoid of hope.

In 1944, following the German occupation of Hungary, Imre Ámos was deported. The exact circumstances of his death are not definitively known, but he is believed to have perished in a German concentration camp, likely Ohrdruf, a subcamp of Buchenwald, sometime in late 1944 or early 1945. He was only 37 years old. His premature death cut short a brilliant artistic career and silenced a unique and vital voice in Hungarian art.

Margit Anna: A Shared Life, A Continued Legacy

The artistic and personal partnership between Imre Ámos and Margit Anna is one of the most compelling stories in Hungarian art history. Their bond was profound, built on mutual respect, shared artistic ideals, and a deep love that sustained them through incredibly difficult times. Margit Anna was not merely a supportive spouse but a formidable artist in her own right. Her work, often featuring puppet-like figures and surreal, sometimes grotesque, imagery, explored themes of alienation, identity, and the absurdity of the human condition.

After Ámos's tragic death, Margit Anna dedicated herself to preserving his memory and his artistic legacy. She carefully curated his remaining works and tirelessly promoted his art. Her own painting continued to evolve, often reflecting her grief and the trauma of loss, but also a fierce resilience. The influence of Ámos can be seen in some of her later works, particularly in their shared symbolic language and emotional depth. Her efforts ensured that Imre Ámos's art would not be forgotten, and she played a crucial role in securing his place in the canon of Hungarian modern art. Her own artistic journey, while distinct, remained intertwined with the memory of her husband, creating a poignant dialogue that transcended his physical absence.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Imre Ámos did not create in a vacuum. He was part of a vibrant, albeit increasingly threatened, artistic community in Hungary. His closest artistic compatriot was Lajos Vajda, whose own work similarly sought to synthesize folk art, Orthodox icons, and modernist principles. Vajda's premature death in 1941 was a significant loss for Ámos and for Hungarian art. Other members of the Szentendre group, such as Dezső Korniss and Endre Bálint (who later became a leading figure in the "European School" art group post-war), shared a common interest in exploring national identity through modern artistic forms.

Beyond Szentendre, the Hungarian art scene included figures like Vilmos Aba-Novák, known for his monumental frescoes and expressive style, and Béla Czóbel, who had strong ties to the Parisian art world and the Fauvist movement. The socially conscious art of Gyula Derkovits offered a stark portrayal of working-class life, while the melancholic, surreal paintings of István Farkas conveyed a sense of unease and impending doom that resonated with the anxieties of the era. Jenő Barcsay, another prominent Szentendre artist, was developing his distinctive constructivist style. The broader European context included not only Chagall but also figures like Chaïm Soutine, whose expressive intensity and Jewish heritage offered another point of reference, and the German Expressionists such as Emil Nolde or Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, whose emotional directness had parallels with Ámos's own expressive tendencies. Ámos's work, while deeply personal, engaged with these broader artistic currents, forging a unique path that was both Hungarian and universal.

Legacy and Enduring Significance

Despite his tragically short life, Imre Ámos left behind a significant body of work that continues to resonate with audiences today. His paintings and drawings are housed in major Hungarian collections, including the Hungarian National Gallery and the Hungarian Jewish Museum, and his art has been featured in numerous exhibitions both in Hungary and internationally.

His legacy lies in his unique ability to fuse Jewish spirituality and folklore with a modern, expressive artistic language. He created a visual world that is both deeply personal and universally accessible, exploring timeless themes of faith, suffering, love, and loss. His art serves as a powerful testament to the horrors of the Holocaust and the resilience of the human spirit in the face of unimaginable adversity.

Art historians and critics recognize Imre Ámos as one of the most important Hungarian artists of the interwar period and the Second World War. His work is valued for its emotional depth, its symbolic richness, and its profound humanity. He is often seen, alongside Lajos Vajda, as a key figure in the development of a distinctively Hungarian modernism that sought to connect with local traditions while engaging with international avant-garde movements. The tragic circumstances of his death only add to the poignancy of his artistic achievement, leaving a lasting impression of a talent extinguished too soon, but whose light continues to shine through his art. His influence, though perhaps primarily felt within Hungary and among scholars of Jewish art and Holocaust art, is undeniable.

Conclusion

Imre Ámos was more than just a painter; he was a visionary, a poet in color and line, and a spiritual seeker. His art charts a journey from the idyllic world of his childhood memories and early artistic explorations to the heart-wrenching realities of persecution and war. He faced the encroaching darkness with an unwavering commitment to his art, using it as a means to affirm his identity, express his deepest fears and hopes, and bear witness to the suffering of his people. His legacy is a collection of works that are at once beautiful and haunting, tender and terrifying. Imre Ámos's art remains a vital reminder of the enduring power of creativity in the face of destruction, and a poignant elegy for a world and a life tragically lost. His voice, though silenced prematurely, continues to speak with profound eloquence through the enduring images he left behind.