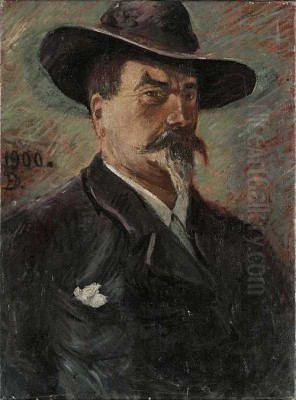

Karl Edvard Diriks stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century European art. A Norwegian painter renowned for his evocative depictions of his homeland's dramatic landscapes and tumultuous seas, Diriks carved a unique niche for himself, bridging the raw naturalism of his Scandinavian roots with the innovative currents of French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. His life (1855-1930) spanned a period of profound artistic transformation, and his work reflects a deep engagement with the changing visual language of his time, all while maintaining a profound connection to the elemental forces of nature that so captivated him.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Norway and Germany

Born in Christiania (now Oslo) in 1855, Karl Edvard Diriks emerged into a Norway that was steadily forging its own cultural and artistic identity. His familial connections provided an early immersion in the artistic milieu; notably, he was a cousin of Edvard Munch, a figure who would later become one of the towering pioneers of Expressionism. This familial tie, while perhaps not a direct stylistic influence in his formative years, undoubtedly placed him within a sphere where art was a vital and discussed part of life.

Diriks's initial academic pursuits, however, were not in painting but in architecture. He traveled to Germany to study this discipline, enrolling in Karlsruhe from 1874 to 1875. While architecture might seem a detour, such training often hones an artist's sense of structure, composition, and spatial awareness – skills that can translate powerfully to the canvas. It was during his subsequent time in Berlin that his path began to pivot more decisively towards painting. In the German capital, he encountered two artists who would prove influential: the Norwegian painter Frits Thaulow and the German artist Max Klinger.

Frits Thaulow, himself a prominent figure in Norwegian art and later an expatriate in France, was known for his atmospheric landscapes and depictions of water. His influence on Diriks likely reinforced a nascent interest in landscape and the natural world. Max Klinger, on the other hand, was a more complex figure associated with Symbolism and a highly imaginative, often allegorical, style. While Diriks's mature work would lean more towards naturalistic and impressionistic renderings, exposure to Klinger's diverse artistic concerns in Berlin could have broadened his understanding of art's expressive possibilities beyond mere representation. Some accounts also mention Max Liebermann, a leading figure of German Impressionism, as an important contact in Berlin, which would further explain Diriks's later receptiveness to French Impressionist ideas.

His formal debut as a painter occurred in his hometown of Christiania in 1879. This marked his public entry into the Norwegian art scene, a community that included figures like Christian Krohg and Harriet Backer, who were also grappling with realism and the burgeoning influence of French art.

The Parisian Crucible: Embracing Impressionism

The allure of Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world in the 19th century, proved irresistible for Diriks, as it did for countless artists seeking innovation and recognition. He made his pivotal move to the French capital between 1882 and 1883. This period was a ferment of artistic revolution. Impressionism, once a radical outlier, had established itself as a powerful force, and its aftershocks were giving rise to Post-Impressionism. Artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, and Auguste Renoir had fundamentally altered the way light, color, and fleeting moments were captured on canvas.

Diriks immersed himself in this stimulating environment. He was quick to absorb the lessons of Impressionism, particularly its emphasis on en plein air (outdoor) painting, the use of broken brushwork to convey the sensation of light, and a brighter, more vibrant palette. His first significant Parisian showcase was at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1883, where he exhibited a work titled La Rue Romaine, likely a depiction of a Parisian street scene, demonstrating his engagement with the urban subjects favored by many Impressionists.

His time in Paris was not spent in isolation. Diriks cultivated relationships with a number of French artists and literary figures. He established close ties with Auguste Renoir, one of the foundational Impressionists, whose influence might be seen in Diriks's handling of light and, at times, a certain sensuousness in his application of paint. He also connected with the poet and playwright Paul Fort and the Belgian poet Émile Verhaeren, indicating his integration into broader cultural circles beyond just painters. These interactions would have provided intellectual stimulation and a deeper understanding of the avant-garde currents shaping European culture. He would also have been aware of, and likely seen works by, other giants of the era such as Paul Cézanne, whose structural concerns were pushing painting in new directions, and perhaps even the emerging talents of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, who were forging their own unique Post-Impressionist paths.

Forging a Distinctive Style: Naturalism and Post-Impressionist Landscapes

While Impressionism provided a crucial catalyst, Karl Edvard Diriks did not simply become a French Impressionist. His artistic identity remained deeply rooted in his Norwegian heritage and a profound connection to the natural world, particularly its more dramatic and untamed aspects. His style evolved into a powerful synthesis of Naturalism – a commitment to depicting the world with fidelity, often focusing on the everyday or the raw power of nature – and Post-Impressionist techniques, which allowed for greater subjective expression, bolder color, and more varied brushwork.

His primary subject matter became the landscapes and seascapes of Norway. He possessed an extraordinary ability to capture the unique atmospheric conditions of the North: the ethereal glow of snow-covered terrains, the heavy, moisture-laden skies pregnant with rain, the dynamic energy of wind sweeping across a fjord, and the awe-inspiring power of ocean storms. Unlike the often sunnier, more placid scenes favored by some French Impressionists, Diriks was drawn to the sublime and often harsh beauty of his native land. His paintings are not merely picturesque views; they are immersive experiences of weather and environment.

His brushwork, initially influenced by the Impressionists' broken color, became increasingly bold and expressive, tailored to the specific textures and energies he sought to convey. He could use broad, sweeping strokes to depict a churning sea or more delicate touches for the subtlety of falling snow or mist. His palette, while brightened by Impressionist influence, often retained a certain Nordic coolness, with a masterful use of blues, grays, whites, and greens, punctuated by warmer tones where appropriate. He was particularly adept at rendering the complex interplay of light on water and snow, capturing reflections and refractions with a keen observational skill.

The Painter of Wind and Waves: Capturing Nature's Drama

Diriks earned a reputation as "the painter of wind and waves," a testament to his singular ability to convey the dynamic and often violent forces of nature. He seemed to possess an intuitive understanding of meteorology, translated into paint. His seascapes are particularly compelling. He didn’t just paint the sea; he painted the experience of the sea – its movement, its sound, its immense power. Works like STORMFULL SJØ I DRØBAK (Stormy Sea in Drøbak) exemplify this focus. In such paintings, the viewer can almost feel the spray of the waves and hear the roar of the wind. The sky and sea often merge in a dramatic symphony of color and form, with clouds scudding across the canvas and waves crashing against rugged coastlines.

His depiction of snow was equally masterful. He captured not just the whiteness of snow, but its myriad textures – powdery, wet, windswept – and the way it transformed the landscape, muffling sounds and creating stark contrasts. He understood the subtle shifts in color within shadows on snow, often using blues and violets to convey coldness and depth. These snow scenes, while sometimes desolate, also possess a quiet beauty and a sense of profound stillness that contrasts with the energy of his maritime paintings.

This focus on the elemental was not unique in Scandinavian art – artists like Peder Balke in an earlier generation had also depicted the sublime power of the Arctic landscape. However, Diriks brought a modern sensibility to these themes, infusing them with the lessons of Impressionism and his own distinctive Post-Impressionist voice. He was less interested in the overtly Romantic or nationalistic interpretations of landscape that characterized some earlier Norwegian art, and more focused on the direct, sensory experience of nature.

Brittany's Rocky Coasts and Continued Exploration

While Norway remained his spiritual and artistic homeland, Diriks also spent considerable time painting in other locations, most notably Brittany in France. The rugged coastline of Brittany, with its dramatic cliffs and powerful Atlantic swells, offered a different but equally compelling subject for his brush. Between 1912 and 1921, he produced a significant body of work there. One of his representative pieces from this period is The Rocky Coast (also known as Rocky Coast in Brittany). These Breton scenes, while sharing thematic similarities with his Norwegian coastal paintings, often exhibit a slightly different light and atmospheric quality, reflecting the distinct character of the region.

His travels were not limited to France and Norway. Early in his career, he reportedly explored northern Norway, Finland, and even ventured as far as Vladivostok, often in the company of his friend Frits Thaulow. These journeys would have exposed him to a wide range of landscapes and climates, further enriching his visual vocabulary and his understanding of nature's diverse manifestations.

An interesting anecdote from his time in Paris mentions him living for a period in a fisherman's hut, which he also used as a studio. This suggests a desire to be close to his subjects, to live and breathe the environment he painted, whether it was the bustling streets of Paris or the more elemental world of the coast. This immersion was key to the authenticity and power of his work.

International Recognition, Exhibitions, and Honours

Karl Edvard Diriks achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime, both in Scandinavia and internationally. His regular participation in the Paris Salons was crucial to building his reputation. He exhibited in the Salon des Indépendants, known for its openness to more avant-garde art, the Salon d'Automne, and the Salon de Printemps. These were highly competitive and prestigious venues, and his consistent presence there indicates the respect he commanded in the Parisian art world.

His work was not confined to Paris. He exhibited in Germany, Denmark, Spain, and Italy, among other countries. This international exposure helped to solidify his standing as a significant European painter. The success of his showing at the Antwerp exhibition in 1901 was a notable milestone. His paintings were admired for their vigorous technique, their powerful evocation of atmosphere, and their unique blend of observation and expression.

The French government recognized his contributions to the arts by awarding him the Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honour) in 1909, a significant accolade for a foreign artist. His native Norway also honored him with the Knight's Cross of the Order of St. Olav. These awards underscore the high esteem in which he was held. His interactions with towering figures of the art world, reportedly including Pablo Picasso and Auguste Rodin, further attest to his integration and standing within the dynamic artistic circles of his time, even if their styles were vastly different. This suggests a mutual respect among artists pushing different boundaries.

A Network of Contemporaries: Influence and Exchange

Diriks's artistic journey was interwoven with a rich network of fellow artists. His cousin, Edvard Munch, though stylistically divergent, represented a powerful force in Norwegian and international art. While Diriks's art generally avoided the intense psychological drama of Munch's work, their shared Norwegian heritage and familial bond likely fostered a mutual awareness and perhaps occasional exchange.

Frits Thaulow was a more direct and formative influence, especially in Diriks's early development as a landscape painter. Their shared travels and Thaulow's own success in Paris would have provided both inspiration and practical connections for Diriks. The encounters in Berlin with Thaulow and either Max Klinger or Max Liebermann (or both) were pivotal in steering him towards a career in painting and exposing him to broader European artistic currents.

In Paris, his connections with Impressionists like Auguste Renoir were significant. He would also have been acutely aware of the work of Claude Monet, whose series paintings and dedication to capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere were revolutionary. The Post-Impressionist landscape, with figures like Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin, provided a backdrop of radical experimentation that Diriks navigated with his own distinct vision. He absorbed lessons from these movements but adapted them to his own temperament and subject matter, never fully relinquishing his commitment to the observable world.

He was part of a generation of Scandinavian artists, including Anders Zorn from Sweden and Vilhelm Hammershøi from Denmark, who gained international recognition in Paris while often retaining strong ties to their native traditions. Within Norway itself, he was a contemporary of artists like Erik Werenskiold and Gerhard Munthe, who were also shaping the course of Norwegian art, often with a focus on national themes and styles. Diriks's contribution was to bring a particularly dynamic and weather-beaten vision of the Norwegian landscape to this broader European conversation.

Later Years in Drøbak and Enduring Legacy

After nearly four decades based primarily in France, Karl Edvard Diriks returned to Norway in 1921. He chose to settle in Drøbak, a coastal town on the Oslofjord. This return to his native shores in his later years seems fitting for an artist whose work was so profoundly connected to the Norwegian environment. Drøbak, with its maritime atmosphere and proximity to the sea, provided continued inspiration for his painting. He remained active as an artist, continuing to create and exhibit his work.

Karl Edvard Diriks passed away in 1930 at the age of 75, leaving behind a substantial body of work. His paintings – landscapes, seascapes, and to a lesser extent, still lifes and figure studies – are found in numerous public and private collections, particularly in Norway and France. Museums such as the National Museum in Oslo hold significant examples of his art.

His legacy lies in his powerful and authentic depictions of the natural world, especially the dramatic coastal and meteorological phenomena of Norway. He successfully fused a deep-rooted Scandinavian sensibility with the progressive artistic language of French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, creating a style that was both modern and deeply personal. He stands as a testament to the enduring power of landscape painting and an artist who truly understood and conveyed the elemental forces that shape our world. While perhaps not as globally famous as his cousin Munch, Diriks made a distinct and valuable contribution to Norwegian and European art, capturing the wild spirit of the North with a brush that was both sensitive and strong.

Conclusion: The Enduring Resonance of Diriks's Vision

Karl Edvard Diriks was more than just a painter of pretty scenes; he was a visual poet of nature's moods, a chronicler of wind, water, and light. His journey from architectural studies in Germany to the heart of the Parisian avant-garde, and finally back to the familiar shores of Norway, reflects a life dedicated to artistic exploration and a profound connection to place. He absorbed the lessons of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, not as a slavish follower, but as an intelligent innovator who adapted these new visual languages to express his own unique vision.

His ability to convey the raw energy of a storm-tossed sea or the quiet desolation of a snowbound landscape remains compelling. Through his dynamic compositions, expressive brushwork, and keen sensitivity to atmospheric effects, Diriks invites viewers to experience the sublime power and beauty of the natural world. His works serve as a powerful reminder of the dramatic interplay between land, sea, and sky, particularly in the northern climes that were his constant inspiration. As an art historian, one appreciates Diriks not only for his technical skill and aesthetic achievements but also for his role as a cultural conduit, bringing a distinctly Norwegian perspective to the international art stage of his era and enriching the broader narrative of European painting. His art continues to resonate, offering a window into the soul of a painter who truly saw, felt, and understood the elemental world around him.