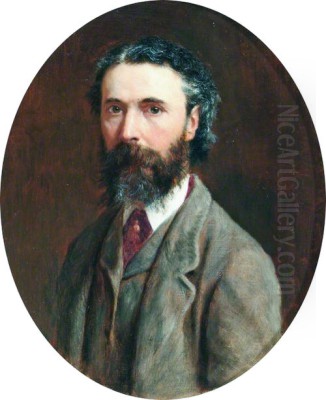

Peter Graham stands as one of the most successful and recognisable Scottish painters of the Victorian era. Born in Edinburgh in 1836 and living until 1921, his career spanned a period of immense change, yet his artistic vision remained remarkably consistent, focused almost entirely on the dramatic landscapes of his native Scotland. He captured the mists, mountains, and rugged coastlines with a skill and atmospheric sensibility that resonated deeply with the public, earning him widespread acclaim, membership in the prestigious Royal Academy of London, and considerable commercial success. His work defined a particular vision of the Highlands for generations, blending Romantic sensibility with Victorian precision.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in Edinburgh

Peter Graham's journey into the art world began in the historic city of Edinburgh, Scotland's capital. Born on March 13, 1836, he grew up in an environment rich with cultural and artistic heritage. His formal art education took place at the Trustees' Academy on Picardy Place, a significant institution that nurtured many of Scotland's finest artistic talents. At the Academy, Graham studied under the influential Robert Scott Lauder, a painter celebrated for his historical scenes and portraits, but also a gifted teacher who encouraged his students to develop their individual styles while grounding them in solid technical skills.

Lauder's tutelage was pivotal. He fostered a generation of artists who would significantly shape Scottish painting in the latter half of the 19th century. Among Graham's fellow students under Lauder were notable figures like William McTaggart, known for his expressive seascapes, and John MacWhirter, who, like Graham, would achieve fame as a landscape painter, particularly of Highland scenes. This period at the Trustees' Academy provided Graham with the essential drawing and painting techniques, and perhaps more importantly, instilled in him a deep appreciation for the power of observation and the expressive potential of landscape. Even in his early work, a preference for natural scenery began to emerge, hinting at the direction his mature career would take.

Initially, however, Graham explored figure painting, following a more conventional academic path. He exhibited figure subjects at the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in Edinburgh during the late 1850s. While these early works showed promise, they did not yet display the unique focus that would later define his reputation. A pivotal sketching trip to Deeside in 1859 seems to have solidified his true calling. Confronted directly with the grandeur and untamed beauty of the Scottish Highlands, Graham found his definitive subject matter. From this point forward, landscape, particularly the wilder aspects of Scotland, would become his primary focus.

The Move to London and Breakthrough Success

Recognising that London was the epicentre of the British art world, offering greater opportunities for exhibition and patronage, Peter Graham made the strategic decision to move south in 1866. This move proved transformative for his career. The same year, he submitted a painting titled A Spate in the Highlands to the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition. This work, depicting a Highland river swollen by heavy rain, captured the dramatic weather and rugged terrain with compelling realism and atmosphere. It was an immediate success, widely praised by critics and the public alike.

A Spate in the Highlands effectively launched Graham's career on the national stage. It showcased his ability to render the specific textures of rock, water, and vegetation while simultaneously conveying the mood and elemental power of the Highland landscape. The painting struck a chord with the Victorian audience, many of whom were captivated by romantic notions of Scotland, fueled by the writings of Sir Walter Scott and the royal family's adoption of Balmoral as a Highland retreat. Graham's work offered a visually stunning and emotionally resonant portrayal of this popularised landscape.

The success of his 1866 RA debut established Graham's reputation almost overnight. He became a regular and eagerly anticipated exhibitor at the Royal Academy. His paintings, often large-scale depictions of Highland glens shrouded in mist, storm-lashed coastlines, or scenes featuring the iconic Highland cattle, consistently drew crowds and commanded high prices. His rise within the academic art establishment was swift. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1877, a significant honour recognising his growing stature. Full membership as a Royal Academician (RA) followed just four years later, in 1881, cementing his position among the elite of the British art world.

Artistic Style: Capturing the Highland Soul

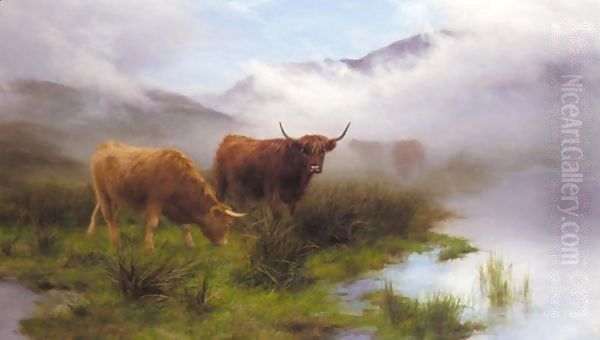

Peter Graham's artistic style is characterised by its focus on atmospheric effects and its detailed yet evocative rendering of the Scottish landscape. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the transient qualities of Highland weather – the swirling mists, the driving rain, the shafts of sunlight breaking through clouds. Mist, in particular, became almost a signature element in his work, used not just for descriptive accuracy but also to create mood, depth, and a sense of mystery. Paintings like Wandering Shadows exemplify this, where mist clings to the mountainsides, partially obscuring and revealing the landscape, lending it an ethereal, almost dreamlike quality.

His technique involved careful observation and detailed rendering, particularly of foreground elements like rocks, heather, and water. This fidelity to nature appealed to the Victorian taste for realism. However, Graham combined this detail with a broader handling of paint in areas like skies and distant mountains, preventing his work from becoming merely photographic. His brushwork, while controlled, could be vigorous, effectively conveying the textures of rough terrain and turbulent water. He paid close attention to the play of light, mastering the depiction of silvery Highland light filtering through clouds or reflecting off wet surfaces.

Highland cattle are another recurring motif in Graham's paintings. These hardy beasts, with their shaggy coats and imposing horns, were perfectly suited to the rugged landscapes he depicted. They added a focal point, a sense of scale, and an element of the picturesque to his scenes. Unlike Sir Edwin Landseer, the dominant animal painter of the era who often anthropomorphised his subjects, Graham depicted the cattle more naturally, as integral parts of their environment. Their presence reinforces the wildness and remoteness of the settings. Works such as Moorland and Mist or Highland Cattle showcase his skill in integrating these animals seamlessly into the landscape composition.

Iconic Works and Enduring Themes

Several paintings stand out as particularly representative of Peter Graham's oeuvre and the themes that preoccupied him. A Spate in the Highlands (1866), his breakthrough work, remains significant not only for its role in launching his career but also for establishing his mastery of depicting dramatic weather and water in a Highland setting. The energy of the rushing river and the damp, misty atmosphere are palpable, showcasing his ability to convey the raw power of nature.

Wandering Shadows (circa 1878) is another quintessential Graham landscape. It depicts a vast Highland glen under a changeable sky, with cloud shadows moving across the slopes. Mist partially veils the distant peaks, creating a sense of immense scale and atmospheric depth. The inclusion of Highland cattle grazing peacefully in the foreground provides a contrast to the wildness of the surrounding mountains. This work perfectly encapsulates Graham's blend of detailed observation, atmospheric effect, and romantic sensibility.

After the Massacre of Glencoe (exhibited 1889) tackles a historical theme, though still firmly rooted in landscape. While not depicting the event itself, the painting evokes the sombre mood of the infamous glen, using the dramatic landscape – steep, dark mountainsides under a brooding sky – to suggest tragedy and loss. The desolate atmosphere is characteristic of Graham's ability to imbue his landscapes with emotional weight. This work demonstrates his capacity to engage with Scotland's history and mythology through the lens of its natural environment.

Coastal scenes also formed an important part of Graham's output. Sea Girt Crags or The Cradle of the Seabird depict the rugged cliffs and turbulent seas of the Scottish coastline, often featuring dramatic waves crashing against rocks and colonies of seabirds perched on ledges. These works showcase his versatility in capturing different aspects of the Scottish environment, from inland glens to exposed maritime locations. He excelled at rendering the movement of water and the textures of wave-battered rock, conveying the wildness and grandeur of the coast.

The Highlands as National Symbol

Peter Graham's career coincided with, and significantly contributed to, the Victorian era's fascination with the Scottish Highlands. This fascination was fueled by various factors, including the Romantic literature of Sir Walter Scott, the accessibility provided by new railways, and Queen Victoria's well-publicised affection for Balmoral Castle. Scotland, particularly the Highlands, came to represent a wild, untamed, and romantic alternative to the increasingly industrialised landscape of England. It was seen as a land of heroic history, sublime scenery, and hardy people.

Graham's paintings perfectly catered to this burgeoning interest. He provided the English art market, centred in London, with compelling and accessible images of this desired landscape. His works offered a sense of escape and adventure, depicting scenes that felt both geographically specific and emotionally universal in their portrayal of nature's power and beauty. He presented the Highlands not just as a place, but as an experience – often misty, melancholic, and majestic. His consistent focus on these themes made him the pre-eminent visual chronicler of the region for many Victorians.

His success demonstrates how landscape painting could tap into national identity and popular sentiment. While born in the Lowlands, Graham became intrinsically associated with the Highlands through his art. His paintings helped solidify a particular visual iconography of Scotland that persists to some extent even today – one dominated by misty mountains, rugged cattle, and dramatic weather. He wasn't necessarily aiming for topographical accuracy in every detail; rather, he sought to capture the spirit and atmosphere of the Highlands as perceived through a romantic Victorian lens. His immense popularity suggests he succeeded brilliantly in this aim.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Peter Graham operated within a thriving Victorian art scene, particularly rich in landscape painting. His training under Robert Scott Lauder placed him alongside other talented Scottish artists like William McTaggart and John MacWhirter. While McTaggart developed a looser, more proto-Impressionist style focused on coastal light and weather, MacWhirter shared Graham's focus on Highland scenery, though often with a brighter palette and a preference for depicting birch trees and autumnal colours. Both, like Graham, achieved considerable success in London.

Another notable Scottish contemporary and friend was Joseph Farquharson, famous for his snow scenes often featuring sheep, earning him the nickname 'The Painting Laird'. Farquharson acknowledged Graham's influence and guidance early in his career, highlighting the supportive network that could exist among artists. Other Scottish landscape painters active during this period included Hamilton Macallum and Colin Hunter, both known for their coastal and marine subjects, often depicting fishing communities and the interplay of light on water. They, too, found favour with the London audience.

In the broader British context, Graham's work can be compared to other popular landscape painters of the day. Benjamin Williams Leader, for instance, painted picturesque English landscapes, often featuring silver birches and tranquil rivers, offering a gentler vision of nature compared to Graham's wilder Scotland. Alfred de Bréanski Sr. also specialized in dramatic landscapes, including Welsh mountains and Scottish lochs, sometimes overlapping in subject matter with Graham. While Graham's work shows an awareness of earlier Romantic landscape traditions, particularly the atmospheric effects reminiscent of J.M.W. Turner, his detailed finish aligns more closely with prevailing Victorian tastes, influenced perhaps indirectly by Pre-Raphaelite attention to detail, though without their specific ideology or techniques.

Within the Royal Academy itself, Graham exhibited alongside the giants of the Victorian art establishment, figures like Frederic Leighton, John Everett Millais, and George Frederic Watts. While their subject matter (often classical, historical, or allegorical) differed greatly from Graham's landscapes, their presence underscores the academic environment in which Graham thrived. His consistent popularity at the RA exhibitions demonstrates how effectively his chosen genre and style met the expectations and desires of the Victorian art-buying public.

The Enduring Friendship with Joseph Farquharson

The relationship between Peter Graham and Joseph Farquharson (1846-1935) is a noteworthy aspect of Graham's professional life. Farquharson, who came from a landed Aberdeenshire family, initially pursued art against his father's wishes. He sought guidance from Peter Graham, who was already establishing himself as a leading landscape painter. Graham provided encouragement and likely practical advice, helping Farquharson develop his skills and confidence.

This mentorship evolved into a lasting friendship. Both artists shared a deep love for the Scottish landscape, although their typical subjects differed – Graham favouring misty mountains and cattle, Farquharson becoming renowned for his luminous snow scenes, often painted from a specially constructed heated hut on wheels that allowed him to work outdoors in winter. Despite these differences, their shared Scottish roots and dedication to landscape painting formed a strong bond.

Their connection highlights the collegial aspects of the Victorian art world, where established artists could play a significant role in nurturing emerging talent. Graham's willingness to support Farquharson speaks well of his character. Farquharson's subsequent success, becoming an RA himself in 1915, is a testament to his own talent, but his early interactions with Graham were undoubtedly formative. Their enduring friendship, spanning several decades, reflects a mutual respect built on shared artistic passions.

Later Career, Legacy, and Conclusion

Peter Graham enjoyed a remarkably stable and successful career long after his initial breakthrough. He continued to paint his signature Highland scenes, maintaining a high level of technical skill and finding a ready market for his work well into the early 20th century. His style did not undergo radical changes; he remained committed to the atmospheric realism that had brought him fame. He continued to exhibit regularly at the Royal Academy and other institutions, his name synonymous with dramatic Scottish landscapes.

He spent his later years primarily in St Andrews, Fife, on the east coast of Scotland, though the Highlands remained his principal artistic inspiration. He passed away there on October 18, 1921, at the age of 85, having been a prominent figure in the British art world for over half a century. At the time of his death, his reputation was perhaps less critically lauded than it had been at its Victorian peak, as newer artistic movements like Post-Impressionism and Modernism had shifted aesthetic tastes. However, his popular appeal endured.

Peter Graham's legacy lies in his powerful and evocative portrayal of the Scottish Highlands. He captured a specific, romanticised vision of his native land that resonated deeply with his contemporaries and helped define Scotland's image for a generation. His technical skill, particularly in rendering atmosphere, weather, and the textures of the landscape, was exceptional. While tastes in art change, Graham's paintings remain highly sought after by collectors and continue to be appreciated for their dramatic beauty and their quintessential representation of the wild Scottish scenery. He stands as a major figure in Scottish art history and a master of Victorian landscape painting. His work remains a compelling window onto both the dramatic landscapes he depicted and the era in which he painted.