Karl Hayd (1882-1945) stands as a noteworthy, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of Austrian art. His life and career spanned a period of immense artistic innovation and profound socio-political upheaval, from the twilight of the Austro-Hungarian Empire through the turmoil of two World Wars. As an art historian, delving into Hayd's world offers a fascinating glimpse into the artistic currents that shaped Central Europe in the first half of the 20th century, and his story provides a lens through which to examine the broader cultural landscape of his time.

Nationality and Professional Background

Karl Hayd was unequivocally Austrian, born in Vienna in 1882. This city, the imperial capital, was a crucible of artistic and intellectual ferment at the turn of the century. His professional background was that of a dedicated painter and, to some extent, a graphic artist. He received his formal artistic training, like many of his contemporaries, at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien). This institution, while steeped in academic tradition, was also a place from which many artists diverged to explore more modern avenues of expression.

Hayd's education would have exposed him to the rigorous demands of academic painting, including drawing from plaster casts and live models, historical painting, and portraiture. However, the Vienna of his youth was also the Vienna of the Secession movement, founded in 1897 by artists like Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, and Josef Hoffmann, who sought to break away from the conservative Künstlerhaus (the established artists' association) and embrace international modern art. While Hayd may not have been a frontline member of the Secession's most radical wing, the spirit of artistic renewal was pervasive and undoubtedly influenced his development. He became a member of the Künstlerhaus himself in 1909, suggesting an initial alignment with more established, yet evolving, artistic circles. Later, he was also associated with the Hagenbund, another significant Viennese artists' association known for its more progressive stance compared to the Künstlerhaus, particularly in embracing Impressionist and Post-Impressionist tendencies.

His professional life was dedicated to the creation of art, primarily oil paintings. He participated in numerous exhibitions throughout his career, showcasing his work to the Viennese public and beyond. His subjects were diverse, encompassing landscapes, portraits, still lifes, and genre scenes, reflecting a versatile artistic practice. He navigated the complex art market of his time, seeking patronage and sales, while also striving for artistic integrity and development. The economic challenges of the interwar period and the subsequent political pressures of the Nazi era would have profoundly impacted his professional life, as they did for all Austrian artists.

Artistic Style and Representative Works

Karl Hayd's artistic style evolved throughout his career, reflecting both his academic training and his engagement with the modernist currents sweeping through Europe. Initially, his work likely bore the hallmarks of late 19th-century academic realism, but he soon embraced the lighter palette and broken brushwork characteristic of Impressionism. His landscapes, in particular, often show a keen sensitivity to light and atmosphere, reminiscent of the French Impressionists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, though filtered through an Austrian sensibility.

A significant portion of Hayd's oeuvre consists of landscapes, often depicting scenes from Vienna and its surroundings, as well as other picturesque Austrian locales. Works such as "Blühender Kirschbaum" (Blooming Cherry Tree) or views of "Heiligenstadt" (a district of Vienna famous for its association with Beethoven) capture the charm of the local environment with a gentle, lyrical quality. His brushwork in these pieces is often lively, and his use of color, while not as radical as the Fauves, demonstrates a clear departure from purely naturalistic representation towards a more subjective interpretation of the scene.

Another important aspect of his output was portraiture. His portraits aimed to capture not just the likeness but also the character of the sitter. While perhaps not as psychologically intense as the portraits by his contemporaries Egon Schiele or Oskar Kokoschka, Hayd's portraits possess a solid craftsmanship and a sympathetic insight. He also painted still lifes, a genre that allowed for experimentation with form, color, and composition. Titles like "Stillleben mit Blumen und Früchten" (Still Life with Flowers and Fruit) are typical, showcasing his ability to render textures and arrange objects in a harmonious and visually appealing manner.

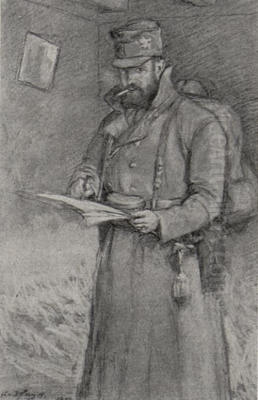

Later in his career, one might observe a consolidation of his style, perhaps with a subtle influence from Post-Impressionist artists like Paul Cézanne in terms of structure, or a more expressive use of color that hints at early Expressionist tendencies, though he never fully embraced the more radical forms of modernism. His work remained largely representational, grounded in a deep appreciation for the visible world, but imbued with a personal artistic vision. Other representative works that illustrate his range include "Donaulandschaft bei Krems" (Danube Landscape near Krems), showcasing his skill in capturing the expansive Austrian river scenery, and various portraits whose titles often simply denote the sitter, such as "Porträt einer Dame" (Portrait of a Lady). His graphic works, though less prominent, would have likely included etchings or drawings, further demonstrating his technical skill.

Life's Trajectory and Significant Milestones

Karl Hayd was born on February 17, 1882, in Vienna, Austria. His early life and decision to pursue art led him to the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, a crucial formative period. He studied there under notable professors such as Christian Griepenkerl and Alois Delug. Griepenkerl was known as a rather conservative history painter, and it's interesting to note that both Egon Schiele and Anton Faistauer had difficult relationships with him. Delug, on the other hand, was also a history painter but perhaps more open, and notably, Adolf Hitler failed the entrance exam to his class. Hayd's successful navigation of the Academy suggests a certain diligence and talent recognized by his tutors.

A significant milestone was his admission to the Vienna Künstlerhaus in 1909. This membership provided him with exhibition opportunities and placed him within the established art community of Vienna. It signified a level of professional recognition. Later, his association with the Hagenbund, which he joined in 1920 and remained a member of until its dissolution by the Nazis in 1938, marked a shift or an expansion of his artistic affiliations towards a more progressive group. The Hagenbund was known for its openness to international art trends and provided a platform for artists who sought alternatives to the more traditional Künstlerhaus.

The interwar period was likely one of active production and exhibition for Hayd. Austria, however, faced severe economic hardship and political instability following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after World War I. Artists struggled, but Vienna's cultural life, though diminished from its pre-war glory, continued. Hayd would have witnessed the rise of Austrian Expressionism, the continued influence of Art Nouveau (Jugendstil), and the emergence of new artistic ideas.

The Anschluss in 1938, when Nazi Germany annexed Austria, was a catastrophic turning point. Artistic freedom was curtailed, Jewish artists and those deemed "degenerate" were persecuted, and art was co-opted for propaganda purposes. The Hagenbund was forcibly dissolved in this year, a clear blow to its members. Hayd's activities during this dark period are less clearly documented in readily available sources, but like all artists who remained in Austria, he would have had to navigate the oppressive cultural policies of the Nazi regime.

Karl Hayd died on November 16, 1945, in Vienna, just months after the end of World War II. His death at the age of 63 occurred as Austria was beginning to grapple with the devastation of the war and its Nazi past, and to slowly rebuild its cultural institutions. His passing at this juncture meant he did not witness much of the post-war artistic reconstruction.

Interactions with Contemporary Painters

Living and working in Vienna, a major European artistic hub, Karl Hayd would have inevitably interacted with a wide array of contemporary painters, or at the very least, been acutely aware of their work and influence. His membership in the Künstlerhaus and later the Hagenbund placed him directly in contact with fellow members and their diverse artistic approaches.

Within the Hagenbund, he would have been associated with artists like Oskar Laske, Anton Faistauer (though Faistauer also co-founded the "Neukunstgruppe" with Schiele), Carry Hauser, and Georg Merkel. The Hagenbund exhibitions were known for their quality and diversity, showcasing a range of styles from late Impressionism to moderate Expressionism. These interactions would have fostered a climate of artistic exchange and mutual influence, even if subtle.

The towering figures of Viennese modernism, Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, and Oskar Kokoschka, created a powerful artistic force in the city. While Hayd's style was generally less radical, he could not have been untouched by their innovations. Klimt's decorative symbolism, Schiele's raw, expressive line, and Kokoschka's psychological portraits redefined Austrian art. Hayd's work, while perhaps more conservative, existed within this dynamic context. He would have seen their exhibitions and participated in the broader artistic discourse they generated.

Other important Austrian artists of his generation or slightly older, whose work he would have known, include Albin Egger-Lienz, known for his monumental depictions of rural life and war; Carl Moll, an early member of the Secession and a key figure in promoting modern art in Vienna; and Rudolf von Alt, the venerable master of Viennese veduta painting whose career spanned much of the 19th century and overlapped with Hayd's early years. Max Oppenheimer (MOPP), another expressive painter, and Richard Gerstl, whose tragically short career produced some of Austria's most intense early Expressionist works, were also part of this vibrant scene, though Gerstl died young in 1908.

Beyond Austria, the influence of international movements was strong. French Impressionists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Post-Impressionists such as Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin, were increasingly known and exhibited in Vienna, partly thanks to the efforts of the Secession and progressive galleries. Hayd's landscape and still life work, in particular, shows an absorption of these influences, adapted to his own artistic temperament. He would have also been aware of German Expressionist groups like Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter, even if his own work did not fully align with their intensity. The artistic environment was one of constant dialogue, competition, and inspiration.

Involvement in Art Movements or Groups

Karl Hayd's primary affiliations with formal art groups were his memberships in the Gesellschaft bildender Künstler Wiens, Künstlerhaus (from 1909) and the Hagenbund (from 1920 until its dissolution in 1938). These memberships are crucial to understanding his position within the Viennese art world.

The Künstlerhaus, founded in 1861, was the traditional bastion of Viennese art. By the time Hayd joined in 1909, it had already seen the departure of the Secessionists but remained a significant institution, hosting large exhibitions and representing a broad spectrum of established artists. Membership conferred a degree of status and provided regular opportunities to exhibit. While sometimes perceived as conservative, the Künstlerhaus also adapted over time, showcasing a variety of artistic styles.

His later membership in the Hagenbund is particularly significant. Founded in 1900, the Hagenbund positioned itself as a more progressive alternative to the Künstlerhaus, though less radical than the initial Secession. It became known as "the moderate moderns" and played a vital role in Viennese art life, especially in the 1920s and 1930s. The Hagenbund was characterized by its stylistic pluralism, embracing artists working in late Impressionist, Expressionist, and New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) styles. Artists like Josef Dobrowsky, Carry Hauser, and the previously mentioned Oskar Laske were prominent members. Hayd's involvement with the Hagenbund suggests his alignment with a more forward-looking, though not avant-garde, segment of the Austrian art scene. The Hagenbund was also notable for its openness to Jewish artists and those with progressive political views, which ultimately led to its forced dissolution by the Nazi regime in 1938, a traumatic event for its members and for Austrian culture.

While Hayd may not have been a founder or a leading ideologue of a specific "movement" in the way Klimt was for the Secession or Schiele for early Austrian Expressionism, his participation in these groups indicates his active engagement with the organized art life of Vienna. These associations provided him with a community of peers, exhibition platforms, and a way to contribute to the evolving artistic discourse of his time. His art, therefore, can be seen as reflecting the broader trends championed or explored within these circles, particularly the Austrian variations of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and a tempered Expressionism.

Experiences During World War II

The period of World War II (1939-1945), and the preceding years following the Anschluss in 1938, were exceptionally challenging for Austrian artists, including Karl Hayd. Austria, as part of the Third Reich (Ostmark), was subjected to Nazi cultural policies. This meant the Gleichschaltung (enforced conformity) of artistic institutions and the promotion of art that aligned with Nazi ideology – heroic, realistic, and celebrating "Aryan" values.

Modern art movements such as Expressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, and Dada were branded as "degenerate art" (Entartete Kunst). Jewish artists, and those politically opposed to the regime, were persecuted, forced into exile, or murdered. Artistic organizations like the Hagenbund, known for its progressive stance and Jewish members, were dissolved in 1938. Hayd, as a member of the Hagenbund, would have directly experienced this suppression.

For artists like Hayd, who were not Jewish and whose style was not overtly "degenerate" in the eyes of the regime, the situation was complex. Some artists chose or were compelled to conform to the new cultural dictates, participating in officially sanctioned exhibitions like the "Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung" (Great German Art Exhibition) in Munich. Others may have retreated into an "inner emigration," continuing to paint privately in their established styles without seeking public approval from the regime, or focusing on politically neutral subjects like landscapes and portraits that did not overtly challenge Nazi aesthetics.

Specific details about Karl Hayd's activities and artistic output during the war years are not widely publicized, which is common for many artists of that generation who were not at the forefront of either resistance or collaboration. It is plausible that he continued to paint, perhaps focusing on landscapes and portraits that were less likely to attract negative attention. The art market would have been severely disrupted, and opportunities for exhibition significantly altered, with the Künstlerhaus now operating under Nazi control.

The war itself brought immense hardship to Vienna, including bombing raids in its later stages. Hayd lived through this entire period, dying in Vienna in November 1945, just six months after the official end of the war in Europe. The city was in ruins, occupied by Allied forces, and facing an uncertain future. His death at this moment meant he did not participate in the post-war cultural reconstruction of Austria, a period when the nation began to confront its recent past and rediscover its suppressed artistic traditions. The impact of the Nazi era and the war on his personal well-being, his artistic production, and his legacy is an area that warrants further, more detailed art historical research.

Anecdotes, Mysteries, or Unresolved Aspects

While Karl Hayd is a documented artist, particularly through his memberships in prominent Viennese art associations and exhibition records, he does not possess the same volume of anecdotal lore or widely discussed "mysteries" as some of his more famous contemporaries like Klimt or Schiele. However, this relative quietude itself can be considered an aspect of his legacy.

One "mystery," or rather an area for further exploration, is the precise nature and extent of his oeuvre, particularly works that may have been lost, destroyed during World War II, or remain in private collections largely unknown to the public. The dispersal and destruction of art during the Nazi era and the war were extensive, and like many artists, Hayd's body of work might be more substantial than currently cataloged in public databases. Tracing the provenance of his paintings could reveal more about his patrons and the reception of his work during his lifetime.

The specifics of his personal life and his day-to-day existence, especially during the tumultuous 1930s and the war years, remain somewhat opaque in general art historical accounts. How did he cope with the dissolution of the Hagenbund? What were his personal views on the political changes? Did he have opportunities to exhibit under the Nazi regime, and if so, what kind of work did he show? These are questions that deeper archival research, perhaps into Künstlerhaus records from that period or personal correspondence if any survives, might illuminate.

There isn't a prominent "unsolved mystery" in the sensational sense, such as a disputed masterpiece or a dramatic personal scandal that has captured public imagination. Instead, the "mystery" surrounding Karl Hayd is perhaps the more common one for many competent and dedicated artists of his era: why some achieve lasting international fame while others, despite significant talent and contribution to their local art scenes, remain primarily figures of national or regional importance. His work is appreciated by collectors of Austrian art, but he has not, to date, been the subject of major international retrospectives that might bring him to broader global attention.

An "anecdote" might simply be the quiet dedication to his craft through decades of profound change. He began his studies in the relatively stable, albeit creatively charged, atmosphere of fin-de-siècle Vienna, lived through the collapse of an empire, the deprivations of a republic, the horrors of Nazism and another world war, all the while continuing to paint. This persistence, in itself, speaks to a deep commitment to his artistic calling. The story of Karl Hayd is a reminder that art history is not only about the most revolutionary figures but also about the many talented artists who contribute to the richness and complexity of a period's cultural expression. His legacy lies in his sensitive depictions of the Austrian landscape and its people, a visual record of a world undergoing irrevocable transformation.