Knute Heldner stands as a significant figure in twentieth-century American art, a Swedish immigrant whose life experiences deeply informed his powerful depictions of both the rugged labor of the working class and the distinctive landscapes of his adopted homeland. His journey from the forests of Sweden to the iron ranges of Minnesota and finally to the vibrant streets and bayous of New Orleans provided a rich tapestry of subjects. Heldner’s work, primarily associated with Social Realism, resonates with a profound empathy for his subjects, capturing their dignity amidst toil and their connection to the environments that shaped them. While biographical details like his exact birth year remain debated (sources suggest either 1877 or 1886), his artistic contributions offer a clear and compelling narrative.

From Sweden to America: An Immigrant's Journey

Born in Vederslov, Smoland, Sweden, Knute Heldner's early life set the stage for his later artistic preoccupations. Sources indicate he received foundational art training in his homeland, attending the Karlskrona Technical School and later studying at the prestigious Royal National Academy in Stockholm. His youth also included a period in the Swedish navy. However, facing economic hardship and reportedly suffering from poor health, Heldner made the pivotal decision to emigrate.

In 1902, he arrived in the United States, initially settling in the northern regions of Minnesota. This marked the beginning of a period characterized by demanding physical labor, experiences that would profoundly influence his artistic vision. America presented both opportunity and challenge, forcing the young artist to rely on resilience and adaptability – traits that would later be reflected in the subjects of his paintings.

Forging an Artist in the American North

Heldner's early years in Minnesota were far removed from the studios of Stockholm. He immersed himself in the world of manual labor, working variously as a logger in the vast timberlands, a miner in the iron ranges, a handyman, a carpenter, and even a cook. These were not mere jobs to sustain himself; they were formative experiences that provided him with intimate knowledge of the lives, struggles, and camaraderie of working-men. This firsthand understanding would become the bedrock of his early artistic output.

Despite the demands of labor, Heldner's commitment to art remained unwavering. He sought further instruction, enrolling at the Minneapolis School of Fine Arts (now the Minneapolis College of Art and Design). There, he studied under influential figures like Robert Koehler, a German-born painter and educator who played a crucial role in developing the Twin Cities' art scene. Koehler's emphasis on solid technique and potentially his own interest in genre scenes may have resonated with Heldner's developing focus.

Early Success and Northern Themes

Heldner's dedication began to yield recognition. A significant turning point occurred in 1915 when he won the prestigious Gold Medal (first prize) at the Minnesota State Fair. This award signaled his arrival as a serious artist within the regional scene and likely provided crucial encouragement. His work during this period predominantly focused on the subjects he knew best: the loggers and miners of the North.

Paintings like "Monument to the Lumberjacks" and "The Lumberjacks" exemplify this phase. These works were not detached observations but empathetic portrayals born from shared experience. He captured the physicality of the labor, the harshness of the environment, and the inherent dignity of the workers. Heldner became associated with a group of Minnesota artists, including figures like David Ericson and Carlson Rawson, whose styles sometimes reflected the influence of French Impressionism, adapted to the unique light and landscape of the American Midwest.

A New Chapter: New Orleans Beckons

The year 1923 marked another significant transition in Heldner's life and art. While in Minnesota, likely connected through the art community or his studies, he met Colette Pope, an aspiring artist. Pope became his student, and their relationship deepened, leading to marriage in 1923. That same year, the couple relocated to New Orleans, Louisiana. This move proved definitive, as Heldner would spend the majority of his remaining career based in the Crescent City.

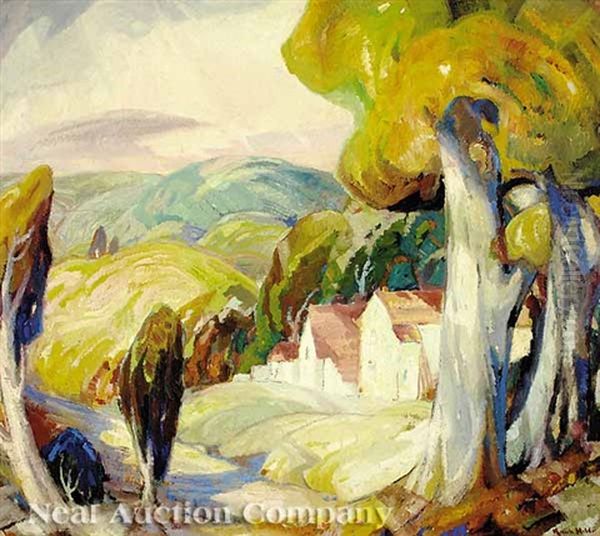

New Orleans offered a stark contrast to the northern landscapes and industries that had previously dominated his canvases. The city's unique culture, historic architecture, vibrant street life, and the surrounding sultry landscapes of the Mississippi Delta provided a wealth of new inspiration. Heldner quickly became an integral part of the city's thriving art community, establishing a studio and reputation in the French Quarter.

Capturing the Spirit of the South

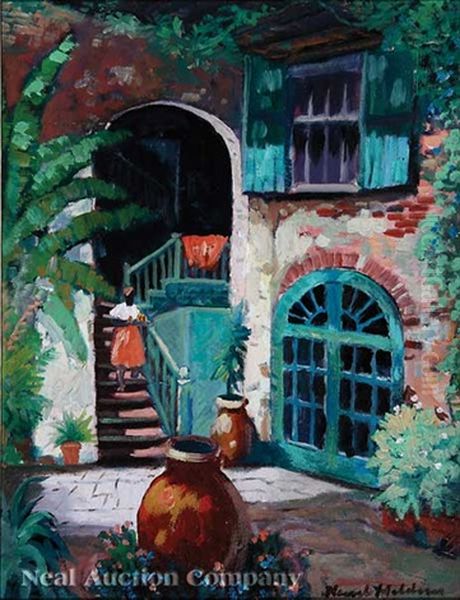

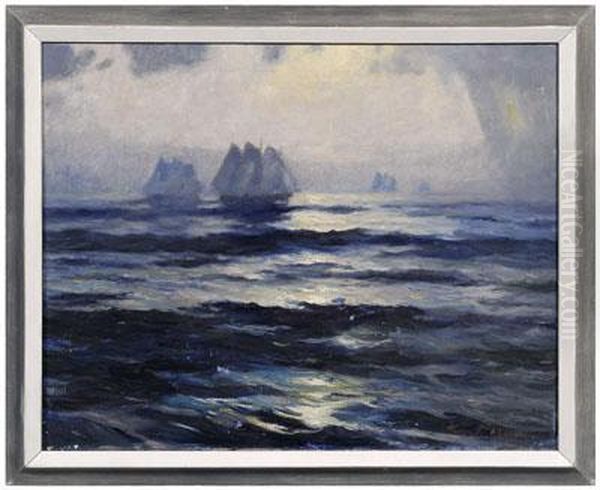

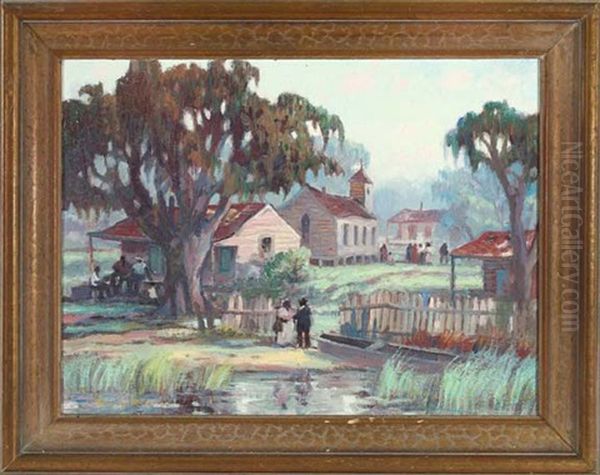

In New Orleans, Heldner's thematic focus shifted, though his underlying empathy for people and place remained constant. He became renowned for his depictions of the French Quarter's picturesque courtyards, such as the subject of his painting "Brulatour Courtyard," capturing the interplay of light, shadow, and aging architecture. The surrounding bayous and coastal areas also drew his attention, leading to works like "Shrimp Boats, No. 5," which depicted the local fishing industry and the lives connected to it.

His interest in the human condition, particularly the lives of laborers, found new expression in the South. He turned his attention to the region's agricultural workers, often depicting African American sharecroppers and field hands. These portrayals are among his most discussed works, reflecting his continued commitment to representing those often overlooked in academic art.

"Love in the Cotton Patch" and Social Realism

One of Heldner's most notable works from his New Orleans period is "Love in the Cotton Patch" (sometimes referred to as "The Cotton Pickers"). This painting depicts Black laborers in a cotton field, rendered with warmth and a focus on human connection amidst their work. It exemplifies Heldner's Social Realist tendencies – an art movement prominent in America during the 1930s and 40s that focused on the everyday lives and struggles of ordinary people, often with an undercurrent of social commentary.

Unlike some Social Realists whose work carried a more overt political edge, such as Ben Shahn or Philip Evergood, Heldner's approach often emphasized individual dignity and shared humanity. His depictions of Southern Black life, while empathetic, have occasionally been discussed in terms of their potential interpretation, with some questioning whether they fully captured the harsh realities of the post-Reconstruction South or perhaps leaned towards a more romanticized view. Nevertheless, these works stand as important documents of his engagement with the social fabric of his adopted home, seeking to portray his subjects with respect. His focus on the worker aligns him broadly with artists like Thomas Hart Benton, though Heldner's style was generally less stylized.

Artistic Style: Versatility and Emotion

Throughout his career, Knute Heldner demonstrated considerable stylistic versatility. While strongly associated with Realism, particularly Social Realism, his work also shows influences from Impressionism, especially in his handling of light and color in landscapes and cityscapes. Some accounts even mention explorations into more abstract modes of expression, indicating an artist willing to experiment beyond his established niche.

His brushwork was often vigorous and expressive, employing texture and impasto to convey the physicality of his subjects and the atmosphere of his scenes. Whether depicting the ruggedness of a miner's face, the shimmering heat of a Louisiana bayou, or the intricate ironwork of a French Quarter balcony, Heldner's technique served his emotional and narrative goals. Color played a crucial role, ranging from the somber earth tones appropriate for mine scenes to the vibrant hues capturing the lushness of the Southern landscape.

Relationships, Teaching, and Influence

Knute Heldner's life was interwoven with the artistic community. His most significant artistic relationship was undoubtedly with his wife, Colette Pope Heldner. Initially his student, she became a respected artist in her own right, particularly known for her Louisiana landscapes painted after Knute's death. While her later style diverged, his initial instruction was formative. Colette remained active in the New Orleans art scene, connecting with artists like Caroline Durie and Josephine Crawford.

Heldner's role as a teacher extended beyond his wife. Marguerite Grossenbach-Barnum is documented as having studied with him, indicating his willingness to share his knowledge. His own education under Robert Koehler highlights the importance of mentorship in his development. Within the broader art communities of both Minnesota and New Orleans, Heldner was a recognized presence. In New Orleans, he worked alongside and exhibited with generations of local artists, contributing to the city's reputation as an art center, a legacy shared by figures like Ellsworth Woodward and William Woodward, who were influential educators at Newcomb College. His connection to the earlier Ashcan School artists like Robert Henri or John Sloan lies more in a shared interest in depicting everyday life, though their urban focus differed from Heldner's later Southern themes.

Recognition, Legacy, and Market Presence

Heldner achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime, extending beyond the Minnesota State Fair prize. His work was exhibited not only regionally but also nationally and even in Europe. An anecdote, mentioned in biographical sources, suggests that President Warren G. Harding expressed admiration for his work, and some accounts state his paintings were hung in the White House, testifying to his national profile.

His legacy is that of an artist deeply connected to the American experience, particularly the dignity of labor and the character of place. He is considered a key figure in Minnesota art history and an important chronicler of New Orleans and the wider South. His work continues to be sought after by collectors and institutions.

Heldner's paintings are held in museum collections, including the LSU Museum of Art in Baton Rouge and the Louisiana Art & Science Museum, which holds an "Untitled" work acquired through the Alma Lee, Norman and Cary Saurage Fund. His works appear regularly on the art market, particularly through auction houses specializing in Southern art, such as the Crescent City Auction Gallery in New Orleans. Recorded sales demonstrate continued interest, with prices varying based on size, subject, and period. For instance, "Rhythm" sold for ,512, while "Brulatour Courtyard" achieved a price between ,500 and ,500, and "Shrimp Boats, No. 5" carried estimates of ,000 to ,000 in past auctions.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Knute Heldner passed away in 1952, with sources conflicting on whether he was 65 or 75 years old. Despite these biographical ambiguities, his artistic legacy is clear. He navigated a path from immigrant laborer to respected professional artist, using his unique life experiences to fuel a body of work characterized by empathy, keen observation, and technical skill. His paintings offer invaluable windows into the worlds of Northern loggers, Minnesota miners, and the diverse inhabitants and landscapes of the American South.

As a Social Realist, he gave voice and visibility to the working people who formed the backbone of the nation, capturing their struggles and resilience without sacrificing their individuality. His landscapes and cityscapes, particularly of New Orleans, convey a deep appreciation for the spirit of place. Knute Heldner remains an important figure in American art history, a bridge between European tradition and American experience, whose canvases continue to speak powerfully of labor, land, and life. His work finds resonance alongside other artists concerned with the American scene, from the regionalists to those focused on social commentary, like Joe Jones, ensuring his enduring relevance.