Karel Holan stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 20th-century Czech art. Born in Prague in 1893 and passing away in the same city in 1953, his life spanned a tumultuous period in European history, encompassing two World Wars and dramatic social and political shifts in Czechoslovakia. Holan distinguished himself primarily as a painter and graphic artist, becoming a key proponent of social art during the interwar period. His deep engagement with the realities of everyday life, particularly the struggles and experiences of the urban working class, cemented his place as an important voice in Czech modernism.

Holan's artistic journey was intrinsically linked with the formation and activities of one of the most notable artists' associations of the era, the Social Group (Sociální skupina). As a founding member, he helped shape an artistic direction that sought to bridge the gap between modern artistic expression and a profound sense of social responsibility. His work offers a compelling window into the social fabric of his time, rendered with both empathy and a keen observational eye.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Karel Holan's artistic path began in Prague, the city that would remain central to his life and work. His formal training took place at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Prague (Akademie výtvarných umění v Praze - AVU). This institution was a crucible for many talents who would define Czech modernism. During his studies, Holan had the invaluable opportunity to learn from prominent figures in the Czech art world, whose influence, even if later reacted against, provided a foundational understanding of technique and artistic thought.

His professors included Vlaho Bukovac, a Croatian painter known for his portraiture and plein-air work, who brought a cosmopolitan flair to the Academy. Jan Preisler, a leading figure of Czech Symbolism and Art Nouveau, imparted a sense of poetic sensitivity and decorative composition. Max Švabinský, a master draftsman and graphic artist, emphasized technical skill and a connection to humanist traditions. Exposure to these diverse artistic personalities provided Holan with a rich, albeit traditional, grounding.

While absorbing the lessons of his teachers, Holan, like many of his generation, began to seek an artistic language more attuned to the rapidly changing modern world and the pressing social issues of the day. The aestheticism of Art Nouveau and the introspective nature of Symbolism gradually gave way to a more direct, realistic, and socially conscious approach in his developing work, setting the stage for his later involvement with the Social Group. He was finding his voice not in idealized visions, but in the unvarnished realities of the city around him.

The Rise of Social Art: Ho-Ho-Ko-Ko and the Social Group

The aftermath of World War I brought profound social and political changes across Europe, and Czechoslovakia was no exception. Artists grappled with the new realities, seeking ways to respond to the societal shifts, the rise of industrialization, and the growing visibility of the urban proletariat. It was within this climate of searching and redefinition that Karel Holan, alongside fellow artists Pravoslav Kotík and Karel Kotrba, founded an informal group in 1924 initially known by the playful acronym Ho-Ho-Ko-Ko (derived from their surnames).

This collective soon evolved and formalized, adopting the more descriptive name Social Group (Sociální skupina). Active primarily between 1924 and 1927, the group became a significant platform for artists committed to exploring social themes through a modern realist lens. They sought to create art that was not detached from life but deeply embedded within it, reflecting the experiences, struggles, and aspirations of ordinary people, particularly the urban working class and the poor.

The ideology of the Social Group was rooted in a sense of ethical responsibility and humanism. They drew inspiration from Czech folk art traditions, valuing its directness and connection to communal life, but combined this with contemporary visual approaches. Their work often carried a critical edge, addressing social inequalities, the harshness of industrial labor, and the alienation felt in rapidly growing cities. There was a shared belief in the moral purpose of art, emphasizing themes of justice, compassion, and solidarity. Miloslav Holý, another prominent painter focused on social themes, was also closely associated with the group's circle and ethos.

The Social Group positioned itself somewhat apart from the more radical avant-garde movements like Czech Cubism, championed by artists such as Emil Filla and Bohumil Kubišta, or the later developments of Poetism and Surrealism associated with figures like Karel Teige, Jindřich Štyrský, and Toyen. While respecting formal innovation, the Social Group prioritized communicative clarity and emotional resonance, aiming to connect directly with the viewer's understanding of the social world. Their approach resonated with international trends like the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement in Germany, which also saw artists like Otto Dix and George Grosz turn a critical eye on contemporary society.

Holan's Artistic Style and Themes

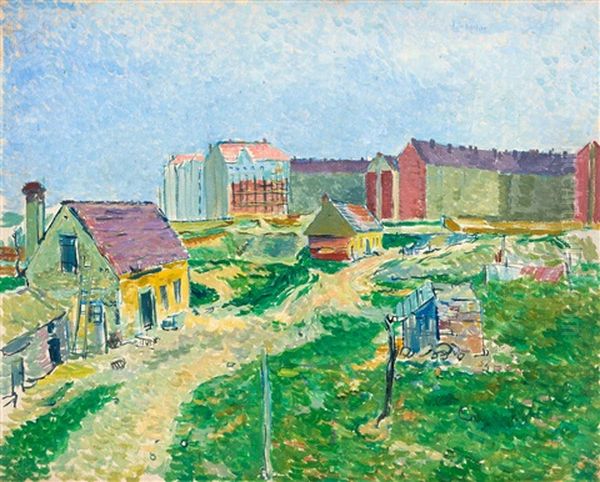

Karel Holan's artistic output is most strongly characterized by his commitment to social realism, particularly in the formative years of the Social Group. His early works often depicted the gritty reality of Prague's outskirts (the "periferie"), industrial areas, harbors, and marketplaces. He painted scenes populated by workers, the unemployed, washerwomen, and street vendors, capturing the atmosphere of working-class neighborhoods with an unsentimental yet deeply empathetic gaze.

His style during this period featured strong, decisive outlines and often a somber color palette, emphasizing the weight and hardship of his subjects' lives. However, his work avoided mere reportage; it sought to convey the inherent dignity and resilience of the individuals he portrayed. Paintings like "Periferie" (Outskirts) or "Dělníci" (Workers) exemplify this phase, showcasing his ability to translate social observation into powerful visual statements. His compositions were often straightforward, focusing attention directly on the human element within the urban environment.

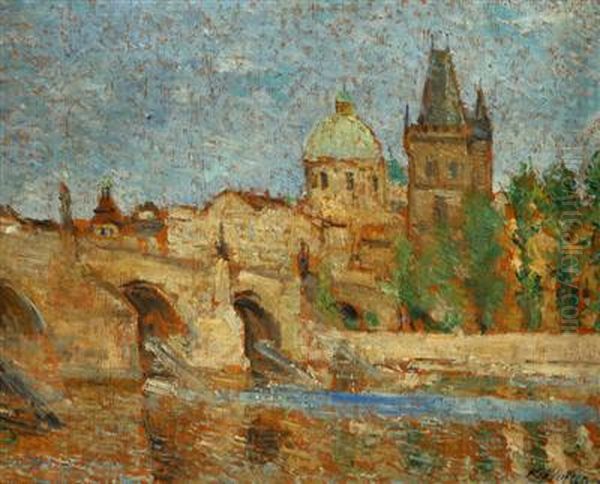

While Holan is best known for these socially charged works, his thematic range broadened over time. He continued to explore urban motifs, capturing views of the Vltava River, Prague's bridges, and bustling street scenes. Landscapes also became a recurring subject, often depicting the Czech countryside with a similar directness and structural solidity found in his urban paintings. Furthermore, Holan produced sensitive portraits and still lifes, demonstrating his versatility and ongoing engagement with different genres.

Throughout his career, Holan maintained a strong connection to graphic arts, producing prints that echoed the themes and stylistic concerns of his paintings. His graphic work often allowed for starker contrasts and a more immediate expressive quality. While his style evolved, it consistently retained a focus on clear representation and emotional weight, distinguishing his work from purely formal experimentation. Within the Social Group, his style could be compared and contrasted with the slightly different approaches of Pravoslav Kotík, whose work sometimes incorporated more expressive distortions, or Karel Kotrba, who also shared the focus on proletarian life.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Karel Holan was an active participant in the Czech art scene, ensuring his work reached the public through various exhibitions. His involvement with the Social Group naturally led to participation in the group's collective shows, which were crucial for establishing their presence and promoting their artistic agenda during the mid-1920s. These exhibitions provided a vital platform for presenting their unique blend of modernism and social commentary to critics and the public alike.

Beyond the Social Group's specific activities, Holan's work was featured in broader surveys of contemporary Czech art. The provided sources mention his participation in significant events such as the Exhibition of Contemporary Culture in Brno (Výstava soudobé kultury v Brně) in 1928, which aimed to showcase the achievements of the First Czechoslovak Republic across various fields, including the arts. His inclusion signaled his recognition as a relevant contemporary artist.

He also exhibited internationally, as indicated by his participation in the Karlovy Vary International Art Exhibition in 1930. That same year, his work was likely included in exhibitions celebrating the centenary of Czech art, reflecting his established position within the national artistic narrative. Furthermore, his contributions were later acknowledged in thematic exhibitions like "New Realisms: Modern Realist Approaches across the Czechoslovak Scene, 1914–1945," which retrospectively highlighted the importance of realist currents, including social art, in Czech modernism.

Holan was also likely associated with or exhibited through the Mánes Union of Fine Arts (Spolek výtvarných umělců Mánes), one of the most important artists' associations in Prague, which organized regular exhibitions featuring a wide spectrum of modern Czech artists. Through these various exhibition activities, Holan solidified his reputation and contributed to the visibility and appreciation of social art within the dynamic Czech art world of the interwar period.

Context and Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Karel Holan's contribution, it's essential to view him within the rich and diverse tapestry of Czech modern art during the first half of the 20th century. The interwar period in Czechoslovakia was a time of intense artistic ferment, with various groups and individuals exploring different paths, from avant-garde experimentation to more traditional forms of modernism. Holan and the Social Group carved out a distinct niche focused on social realism.

Their work can be seen as a response, in part, to the earlier wave of Czech Cubism, which had dominated the Prague scene before World War I with artists like Emil Filla, Bohumil Kubišta, Antonín Procházka, and the sculptor Otto Gutfreund. While the Social Group embraced modern formal simplifications, they rejected what they might have seen as the excessive formalism or elitism of Cubism, seeking instead a more accessible and socially relevant art.

They also coexisted with other significant movements. The group Tvrdošíjní (The Stubborns), active shortly after WWI, included figures like Josef Čapek, Jan Zrzavý, Václav Špála, and Rudolf Kremlička, who explored various modernist idioms, often with a uniquely Czech character. Zrzavý, for instance, developed a highly personal, lyrical style, while Josef Čapek (brother of the writer Karel Čapek) moved towards a simplified, expressive figuration that also touched upon social themes. Rudolf Kremlička, though sometimes associated with the Tvrdošíjní, also produced sensitive depictions of female figures and working life that bear comparison with social art.

Later, Czech art saw the rise of Surrealism, with key figures like Jindřich Štyrský, Toyen (Marie Čermínová), and the theorist Karel Teige pushing the boundaries of artistic expression in different directions. Holan's commitment to realism set him apart from these more psychologically focused or abstract tendencies. His contemporaries also included painters like Willi Nowak, known for his sensitive portraits and landscapes, and Jan Bauch, whose expressive, often dramatically rendered figures occupied a different space in the artistic landscape.

Internationally, as mentioned, the Social Group's concerns paralleled those of the German New Objectivity artists (Otto Dix, George Grosz, Christian Schad, Käthe Kollwitz) and perhaps certain aspects of Belgian Expressionism (Constant Permeke). Holan's work, therefore, participated in a broader European conversation about the role of art in reflecting and commenting upon modern society, particularly in the wake of war and industrialization.

Later Career and Legacy

Information regarding Karel Holan's specific activities during the later 1930s, the German occupation, and the post-World War II era is less prominent than details about his crucial role in the Social Group during the 1920s. However, it is understood that he continued to paint and create graphic work throughout these challenging periods. The changing political landscape, particularly the imposition of Socialist Realism as the official doctrine after the Communist takeover in 1948, would have presented a complex environment for artists like Holan whose earlier social concerns might seem superficially aligned but whose artistic independence could be at odds with state dictates.

Holan passed away in 1953, leaving behind a body of work that stands as a testament to a specific and significant current within Czech modernism. His primary legacy lies in his contribution to social art. Alongside Pravoslav Kotík, Karel Kotrba, and Miloslav Holý, he helped define a movement that brought the lives of ordinary Czechs, particularly the urban poor and working class, into the realm of serious artistic consideration. He did so with a visual language that was modern yet accessible, prioritizing human empathy and social awareness.

His paintings and prints serve not only as artistic achievements but also as valuable historical documents, offering insights into the social conditions and atmosphere of Prague and Czechoslovakia during the interwar years. They capture the anxieties, the struggles, but also the enduring spirit of people living through a period of rapid change and economic hardship. Holan's commitment to depicting the "periferie" – the often-overlooked margins of the city – gave visibility to subjects previously neglected in mainstream art.

While perhaps not as internationally famous as some of the Czech avant-garde figures, Karel Holan holds a secure place in Czech art history as a key representative of social realism and a sensitive chronicler of his time. His work continues to resonate for its powerful blend of artistic skill and profound humanism.

Conclusion

Karel Holan remains an essential figure for understanding the breadth and depth of Czech art in the 20th century. As a painter, graphic artist, and founding member of the influential Social Group, he dedicated much of his career to exploring the social realities of his time, particularly the lives of the working class in urban Prague. His studies under notable figures at the Academy of Fine Arts provided a solid foundation, but it was his engagement with the post-WWI world that truly shaped his artistic direction.

Through his association with Pravoslav Kotík, Karel Kotrba, and others in the Social Group, Holan championed an art form that was both modern in its visual language and deeply committed to social commentary and human empathy. His depictions of Prague's outskirts, industrial scenes, and everyday people are rendered with a characteristic blend of realism, strong composition, and emotional weight. While his thematic focus expanded over time to include landscapes and portraits, his work consistently maintained a connection to the tangible world and the human condition.

Positioned within a vibrant Czech art scene that included diverse movements from Cubism to Surrealism, Holan and the Social Group carved out a unique path centered on social consciousness. His participation in key national and international exhibitions ensured the visibility of this artistic current. Karel Holan's legacy endures through his compelling body of work, which offers both a valuable artistic contribution and a poignant social chronicle of interwar Czechoslovakia. He remains a significant voice, reminding us of art's power to reflect, question, and connect with the human experience in its varied social contexts.