Konstantin Ivanovich Gorbatov stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of Russian art history. Primarily recognized as a Post-Impressionist landscape painter, his work resonates with a unique blend of Russian lyricism and European modernist techniques. Born in the heartland of Russia and later finding himself an émigré in Europe, Gorbatov's art charts a course through changing times, personal displacement, and an unwavering dedication to capturing the beauty he perceived in the world, whether it was the snow-laden monasteries of his homeland or the sun-drenched vistas of Italy. His life (1876-1945) spanned a tumultuous period, encompassing the twilight of the Tsarist empire, revolution, and two world wars, experiences that subtly permeated his luminous and often idyllic canvases.

Gorbatov's artistic identity is characterized by a profound sensitivity to light and color, an elegance of composition, and a distinctively poetic, almost romantic, atmosphere. While often associated with Impressionism due to his vibrant palette and attention to atmospheric effects, his work retains a structural solidity and emotional depth that aligns it more closely with Post-Impressionism, infused with a uniquely Russian sensibility. He sought not merely to replicate reality but to distill its essence, creating scenes that feel both observed and deeply felt.

Early Life and Formative Years

Konstantin Ivanovich Gorbatov was born on May 17 (May 5, Old Style), 1876, in the town of Stavropol-on-Volga, located in the Samara Governorate of the Russian Empire (now the city of Tolyatti). Situated on the banks of the mighty Volga River, this environment likely provided early, formative impressions of the vast Russian landscapes that would later feature prominently in his art. His initial education, however, was not directed towards the arts. He first attended the Samara Real School before moving to Riga.

In Riga, Gorbatov enrolled at the Polytechnic Institute, initially pursuing studies in civil engineering. This technical background might seem distant from his eventual path, yet it perhaps instilled in him a sense of structure and precision that subtly underpins his later artistic compositions. The pull towards art proved stronger, however, and he soon shifted his focus. He began taking art classes, laying the groundwork for a future dedicated to painting.

The decisive step in his artistic education came when he moved to the imperial capital, Saint Petersburg. Between 1904 and 1911, Gorbatov studied at the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts. Initially, he entered the architecture department, perhaps bridging his earlier technical training with his artistic aspirations. However, he ultimately transferred to the painting department, finding his true calling under the tutelage of Professor Nikolai Nikanorovich Dubovskoy, a respected landscape painter associated with the later phase of the Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) movement. Dubovskoy's influence likely reinforced Gorbatov's inclination towards landscape painting and possibly introduced him to the nuances of capturing the specific moods and light of the Russian environment.

The Allure of Italy: Capri and Rome

A pivotal moment in Gorbatov's development occurred upon his graduation from the Academy in 1911. His talent was recognized, and he was awarded a scholarship that enabled him to travel abroad for further study and artistic exploration. Like many Russian artists before and after him, Gorbatov was drawn to the sunlit landscapes and rich artistic heritage of Italy. He initially traveled to Rome, immersing himself in the city's classical ruins and Renaissance masterpieces.

During his time in Rome, he connected with other Russian artists who were also studying or working there. Sources mention his association with figures like Nikolay Petrovich Golorev and Vadim Falileyev, indicating his integration into the expatriate Russian artistic community. This period abroad was crucial; it exposed him directly to European art movements and, most importantly, to the unique quality of Mediterranean light and color, which contrasted sharply with the more muted tones of northern Russia.

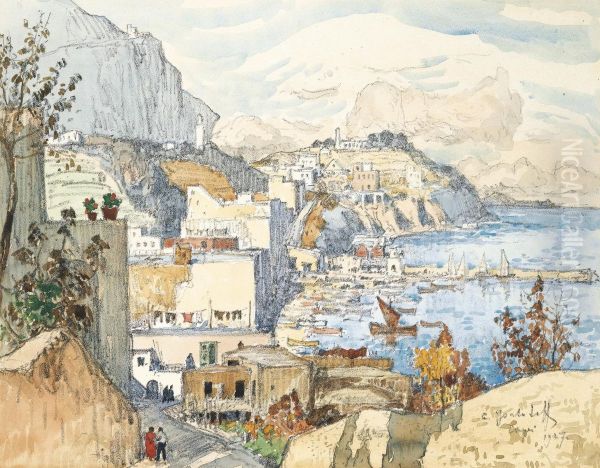

Gorbatov soon found a particular affinity for the island of Capri. He spent considerable time there, captivated by its dramatic cliffs, sparkling blue waters, and vibrant local life. The intense sunlight and vivid colors of the island profoundly impacted his palette, pushing it towards the brighter hues and broken brushwork characteristic of Impressionism. His Italian landscapes from this period are imbued with a sense of warmth, joy, and atmospheric brilliance, showcasing his mastery in rendering the effects of light on water and architecture. This Italian sojourn was not just a study trip; it became a deep source of inspiration that he would return to throughout his career.

Return to Russia: Capturing the Motherland

After his formative experiences in Europe, Gorbatov returned to Russia. He brought back with him a refined technique and a heightened sensitivity to color and light, which he now applied to the landscapes of his homeland. He traveled extensively within Russia, painting scenes along the Volga River, in ancient cities like Pskov and Novgorod, and capturing the quiet beauty of provincial towns and monasteries.

His Russian landscapes possess a different mood compared to his Italian works. While still demonstrating his command of color, they often evoke a sense of tranquility, nostalgia, and the specific atmosphere of the Russian seasons. He was particularly adept at depicting winter scenes, rendering the crisp air, sparkling snow, and the stark beauty of monasteries against a winter sky with poetic grace. Works from this period often feature historical architecture, reflecting an interest in Russia's past and cultural heritage.

During these pre-revolutionary years, Gorbatov began to establish his reputation within the Russian art world. He participated in various exhibitions, including those associated with the later Peredvizhniki and potentially other groups active in the vibrant artistic milieu of the Silver Age. His paintings were appreciated for their lyrical quality, technical skill, and the harmonious blend of observed reality with a romanticized vision. He was developing his signature style – one that celebrated beauty and found poetry in the everyday landscapes of Russia.

Artistic Style: Between Impressionism and Romanticism

Defining Gorbatov's style requires acknowledging its nuanced position within early 20th-century art. While frequently labeled an Impressionist or Post-Impressionist, his work resists easy categorization. He certainly absorbed Impressionist techniques, particularly during and after his time in Italy. This is evident in his use of vibrant, often unmixed colors, broken brushwork to capture fleeting effects of light, and an emphasis on plein air observation. His paintings shimmer with atmospheric light, whether it's the dazzling Mediterranean sun or the softer glow of a Russian sunset.

However, Gorbatov did not fully dissolve form in light as the French Impressionists sometimes did. His compositions retain a sense of structure and solidity. Furthermore, a strong current of Romanticism runs through his work. This connects him to earlier Russian landscape traditions, notably the work of artists like Arkhip Kuindzhi, known for his dramatic light effects and romanticized views of nature. Gorbatov himself reportedly stated that he aimed to paint "not life as it is, but as it could be," suggesting a desire to depict an idealized, more beautiful version of reality.

His paintings often evoke a specific mood – serenity, nostalgia, quiet contemplation, or joyful vibrancy. This emotional resonance, combined with his focus on picturesque motifs (old churches, tranquil rivers, scenic coastlines), aligns him with a lyrical landscape tradition. His color palette, while bright, is always harmonious, carefully orchestrated to create a pleasing and evocative effect. He masterfully balanced observation with interpretation, technique with feeling, resulting in works that are both visually appealing and emotionally engaging.

Masterpieces and Enduring Themes

Several works stand out as representative of Gorbatov's artistic achievements and recurring themes. His Winter Russian Monastery (1909), painted even before his main Italian sojourn, exemplifies his early ability to capture the unique atmosphere of the Russian winter. The painting uses cool blues and whites, accented by the warm glow of lights or gilded domes, to convey both the stillness and the spiritual presence of the monastery in the snow-covered landscape. It's a work imbued with poetry and a sense of timelessness.

In contrast, his numerous paintings of Capri, such as Capri (1939), showcase the impact of his time in Italy. These works burst with color – the deep blues of the sea and sky, the warm ochres and pinks of the buildings, the bright greens of vegetation. He captures the intense sunlight, the bustling life of the harbors, and the dramatic coastal scenery with evident delight. These paintings are celebrations of light, warmth, and the picturesque beauty of the Mediterranean.

Gorbatov was also drawn to Venice, another city famed for its unique light and atmosphere. Works like A Small Town near Venice depict the canals, bridges, and distinctive architecture, focusing on the interplay of light and reflection on the water. These Venetian scenes often possess a dreamlike quality, blending topographical accuracy with a romanticized vision of the city.

A later work, Rostov Veliky (reportedly painted around 1943 during World War II), holds particular significance. Depicting one of Russia's oldest and most revered cities, known for its stunning kremlin and churches, this painting can be seen as an expression of patriotism and cultural pride during a time of national crisis. It underscores his enduring connection to his homeland, even while living in exile. Across these diverse subjects, the common threads are Gorbatov's love for picturesque scenery, his mastery of light and color, and his ability to infuse his landscapes with a palpable sense of mood and atmosphere.

Exile: Life and Art in Italy and Berlin

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent Civil War dramatically altered the course of Gorbatov's life and career. Like many artists and intellectuals uncomfortable with the new regime or fearing the turmoil, Gorbatov chose emigration. In 1922, he left Russia with his wife, Olga, never to return. They initially settled back in Italy, drawn perhaps to the familiar and beloved landscapes of Capri where they lived for several years.

Life in exile presented new challenges. While Italy provided artistic inspiration, the market for his work may have shifted, and financial stability was not always guaranteed. Despite these potential hardships, Gorbatov continued to paint prolifically, refining his style and producing many of his most characteristic Italian landscapes during this period. His art became, in part, a refuge – a continued celebration of beauty in a world marked by upheaval. It also likely carried undertones of nostalgia for the Russia he had left behind.

In 1926, the Gorbatovs relocated to Berlin. Germany's capital was then a major center for Russian émigrés, offering a semblance of community and potential opportunities. Gorbatov achieved some success in Germany, participating in exhibitions, including a notable one featuring Russian art in Cologne in 1929, which was well-received by the public. He continued to paint, sometimes revisiting Russian themes from memory or imagination, alongside his popular Italian scenes. Berlin offered a different urban environment, though his primary focus remained on landscapes, often imbued with a sense of peace that contrasted with the growing political tensions in Europe.

The War Years, Final Days, and Legacy

The rise of Nazism in Germany cast a dark shadow over Gorbatov's later years. As World War II approached and then engulfed Europe, his situation became increasingly precarious. As a Russian émigré, even one not aligned with the Soviet regime, his position in Nazi Germany was difficult. Sources suggest that during the war, German authorities prohibited him and his wife from leaving the country. They were essentially trapped in Berlin as the conflict raged.

This period must have been one of immense hardship and anxiety. Despite the grim circumstances, Gorbatov reportedly continued to work when possible, finding solace in his art. His death on May 24, 1945, came shortly after the end of the war in Europe and the fall of Berlin to Allied forces. He was 69 years old. His wife, Olga, is believed to have died around the same time or shortly thereafter.

Konstantin Gorbatov left behind a significant body of work. According to his will, he wished for his artistic legacy to be returned to his homeland, Russia. After his death, his paintings were initially held by Soviet authorities. Eventually, a large collection of his works found a permanent home not in a major Moscow or St. Petersburg museum, but at the New Jerusalem Monastery Museum (now the State Historical, Architectural and Art Museum "New Jerusalem") in Istra, near Moscow. This somewhat peripheral location contributed to his relative obscurity within Russia for many decades, especially during the Soviet era when émigré artists and non-Socialist Realist styles were often marginalized.

Gorbatov in Context: Contemporaries and Influences

To fully appreciate Konstantin Gorbatov's place in art history, it's helpful to consider him alongside his contemporaries and the broader artistic currents of his time. The late 19th and early 20th centuries in Russia, often referred to as the Silver Age, were a period of intense artistic ferment, with various movements flourishing alongside and influencing one another.

Gorbatov emerged during a time when the dominance of the Peredvizhniki (Wanderers), with their focus on critical realism and social commentary, was waning, though still influential (as seen in his teacher, Dubovskoy). New artistic groups and styles were emerging, embracing aestheticism, symbolism, and modern European trends like Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

Key figures whose careers overlapped with Gorbatov's include:

Isaac Levitan (1860-1900): Though he died early, Levitan perfected the "mood landscape," a lyrical and deeply Russian interpretation of nature that certainly influenced later landscape painters, perhaps including Gorbatov's sense of atmosphere.

Valentin Serov (1865-1911): A brilliant portraitist and landscape painter, Serov masterfully incorporated Impressionist techniques into a fundamentally realist framework. His sophisticated handling of light and color set a high standard.

Konstantin Korovin (1861-1939): Often considered the leading Russian Impressionist, Korovin fully embraced the style's vibrant palette and spontaneous brushwork, particularly in his Parisian scenes and still lifes. Like Gorbatov, he also emigrated after the Revolution.

Igor Grabar (1871-1960): An artist, art historian, and restorer, Grabar was a prominent exponent of Russian Impressionism, known especially for his dazzling snow scenes employing pointillist techniques.

Arkhip Kuindzhi (1842-1910): A major influence on many, including Gorbatov, Kuindzhi was famed for his dramatic, almost theatrical, depictions of light and his romanticized vision of nature.

Mikhail Nesterov (1862-1942): Associated with Symbolism, Nesterov combined landscape with spiritual and religious themes, creating poetic and contemplative works often featuring monks or saints in serene natural settings. Gorbatov's monastery paintings share some of this contemplative mood.

Konstantin Yuon (1875-1958): A contemporary born just a year before Gorbatov, Yuon was known for his colorful depictions of Russian provincial life, historical architecture, and landscapes, often with Impressionist influences.

Abram Arkhipov (1862-1930): Initially a Realist depicting peasant life, Arkhipov later adopted a brighter palette and looser brushwork, influenced by Impressionism.

Ilya Repin (1844-1930): The towering figure of Russian Realism, Repin's influence was pervasive, though Gorbatov moved in a different stylistic direction. Repin also spent his final years in exile (in Finland).

Leonid Pasternak (1862-1945): Father of the writer Boris Pasternak, Leonid was an accomplished painter often associated with Impressionism, known for his intimate portraits and genre scenes. He also emigrated and died the same year as Gorbatov.

Vasily Polenov (1844-1927): A versatile artist known for landscapes and historical scenes, Polenov was an influential teacher whose work sometimes incorporated plein air principles.

Nikolai Roerich (1874-1947): A unique figure interested in archaeology, mysticism, and Symbolism, Roerich created stunning, stylized landscapes, particularly of the Himalayas, using bold colors.

While direct collaboration between Gorbatov and many of these figures isn't documented (and the provided snippets explicitly state no known interaction with Pasternak, Kuprin, Kukushkin, or Repin beyond being contemporaries), they formed the artistic ecosystem in which he developed. Gorbatov navigated these currents, absorbing influences from Russian traditions (lyrical landscape, Kuindzhi's romanticism) and European modernism (Impressionism, Post-Impressionism) to forge his own distinctive path. His focus remained steadfastly on the landscape, rendered with technical skill and a deeply personal, poetic sensibility.

Critical Reception and Enduring Appeal

Konstantin Gorbatov's critical reception has evolved over time. During his lifetime, particularly in the pre-revolutionary period and during his early years in exile, he achieved a degree of recognition, exhibiting his work and finding buyers. His paintings, with their accessible beauty and technical polish, appealed to collectors who appreciated traditional landscape painting infused with modern color sensibilities. His success in Germany in the late 1920s attests to his appeal beyond a purely Russian audience.

However, within the Soviet Union, his status as an émigré and his adherence to a style far removed from the mandated Socialist Realism led to his marginalization. His name and work were largely absent from official Soviet art histories for much of the 20th century. The placement of his main collection in the relatively remote New Jerusalem Monastery Museum further limited his visibility within his homeland.

In the post-Soviet era and internationally, there has been a renewed interest in Gorbatov's work. Art historians and collectors recognize the quality and charm of his paintings. His works appear at international auctions, sometimes fetching significant prices, indicating a strong market appreciation for his art, particularly his luminous Italian and Venetian scenes. He is now increasingly acknowledged as an important representative of Russian Post-Impressionism, a skilled colorist, and a master of lyrical landscape.

The enduring appeal of Gorbatov's art lies in its combination of technical mastery and emotional warmth. His paintings offer viewers moments of beauty, tranquility, and escape. Whether depicting the quiet dignity of a Russian monastery under snow, the vibrant energy of a Capri harbor, or the shimmering reflections in a Venetian canal, his works consistently convey a deep appreciation for the visual world and an ability to translate that appreciation into harmonious and evocative images. His art stands as a testament to a life dedicated to beauty, bridging Russian and European traditions through periods of profound historical change.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Light

Konstantin Ivanovich Gorbatov navigated a complex path, both geographically and artistically. From the banks of the Volga to the shores of Capri and the streets of Berlin, his life journey mirrored the turbulent history of his times. As an artist, he skillfully synthesized the traditions of Russian landscape painting with the innovations of European Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, creating a body of work characterized by its luminous color, elegant composition, and pervasive poetic atmosphere.

Though perhaps overshadowed during the Soviet period due to his emigration, Gorbatov's legacy endures. His paintings continue to captivate viewers with their serene beauty and technical brilliance. He remains a significant figure for understanding the diversity of Russian art in the early 20th century and the experiences of the Russian artistic diaspora. His works, preserved primarily in the New Jerusalem Museum and in collections around the world, serve as a lasting reminder of his unique vision – a world bathed in harmonious light, where nature and architecture coexist in picturesque tranquility, filtered through the lens of a sensitive and romantic soul. Gorbatov's art is a quiet but persistent celebration of the beauty that can be found, even amidst exile and uncertainty.