Louis Marcoussis stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the narrative of early 20th-century modern art. Born in Poland but intrinsically linked to the vibrant artistic crucible of Paris, Marcoussis navigated the transition from Impressionism to the revolutionary language of Cubism, leaving behind a rich legacy as both a painter and a master printmaker. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the collaborations, innovations, and challenges faced by artists during one of art history's most dynamic periods.

From Warsaw to Paris: Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born Ludwig Casimir Ladislas Markus in Warsaw, Poland, on November 14, 1878, the artist later known as Louis Marcoussis initially pursued a different path. He began by studying law in his native city, a conventional start that soon gave way to his true calling. His artistic inclinations led him to the prestigious Kraków Academy of Fine Arts. There, he honed his foundational skills under the tutelage of notable Polish artists Jan Stanislawski, known for his evocative landscapes, and Józef Mehoffer, a leading figure of the Young Poland movement celebrated for his stained glass and paintings.

The magnetic pull of Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world at the turn of the century, proved irresistible. In 1903, Markus moved to the French metropolis, immersing himself in its bohemian atmosphere. He continued his formal art education at the renowned Académie Julian, studying under the academic painter Jules Lefebvre. This period was crucial for networking; he formed friendships with fellow artists like Roger de La Fresnaye and Robert Lotiron, individuals who, like him, were absorbing the city's artistic currents. To support himself, Markus embraced commercial work, creating caricatures for popular satirical magazines such as La Vie Parisienne and Le Journal. This work, while perhaps secondary to his fine art aspirations, sharpened his observational skills and kept him connected to Parisian life and culture.

The Impressionist Echo and the Cubist Calling

Like many artists arriving in Paris during that era, Marcoussis's initial works bore the imprint of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. The emphasis on light, color, and capturing fleeting moments was a dominant force he absorbed. He began exhibiting his work relatively early, participating in the influential Salon d'Automne starting in 1905 and the Salon des Indépendants from 1906. These large, juried exhibitions were vital platforms for artists seeking recognition and engagement with the public and critics.

However, the artistic landscape of Paris was undergoing a seismic shift. The Fauvist explosion of color led by Henri Matisse and André Derain had challenged traditional representation, but an even more radical transformation was brewing in the studios of Montmartre. Around 1907, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque began developing a new visual language – Cubism – that fractured objects and depicted them from multiple viewpoints simultaneously. Marcoussis was drawn into this vortex of innovation. By 1910, his work began to show a decisive move away from Impressionist aesthetics towards the geometric structures and analytical approach of early Cubism. This transition marked the beginning of his most significant artistic phase.

Marcoussis and the Language of Cubism

Marcoussis quickly became associated with the Cubist movement, establishing connections with its primary instigators, Picasso and Braque, as well as other key figures like Juan Gris and the poet-critic Guillaume Apollinaire, who became a fervent supporter and theorist of the movement. It was Apollinaire, known for his wit and wordplay, who suggested Markus adopt the French-sounding name "Marcoussis," after a village near Paris, to aid his integration into the French art scene.

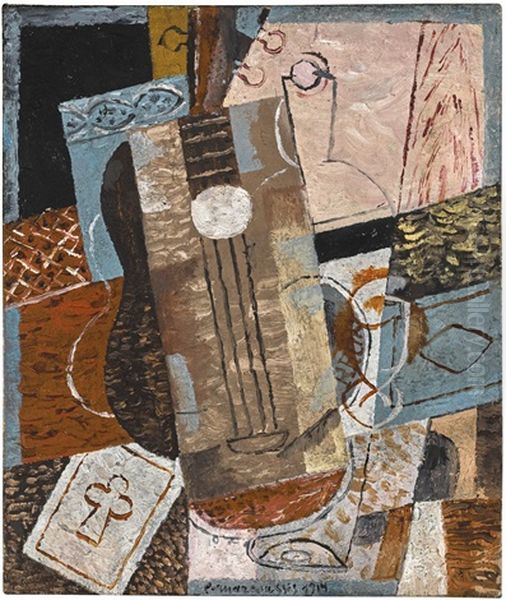

Marcoussis developed his own distinct interpretation of Cubism. While adhering to its core principles – the fragmentation of form, the flattening of space, the use of multiple perspectives, and often a subdued palette – his work sometimes retained a lyrical quality or a decorative sensibility that distinguished it from the more austere analytical works of Picasso and Braque's earliest phase. He frequently depicted subjects common to Cubist still lifes: musical instruments (violins, guitars), bottles, glasses, playing cards, and tabletops, exploring their forms through geometric deconstruction and reconstruction.

His 1912 painting, Still Life with a Checkerboard (Nature morte au damier), serves as an excellent example of his Cubist style during this period. The composition features familiar objects arranged on a table, fragmented into overlapping planes and geometric shapes. The checkerboard itself becomes a dynamic element, integrated into the complex spatial structure. The palette is relatively muted, typical of Analytical Cubism, focusing attention on the formal arrangement and the interplay of lines and shapes. Marcoussis demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of Cubist principles, contributing thoughtfully to the movement's visual discourse.

The Section d'Or: A Collective Vision

While Picasso and Braque initially developed Cubism in relative seclusion, the movement quickly attracted a wider circle of artists eager to explore its potential. Marcoussis became associated with the Puteaux Group, a gathering of artists and writers who met near Paris in the studio of Jacques Villon and his brothers, Raymond Duchamp-Villon and Marcel Duchamp. This group sought to create a more public and theoretically grounded version of Cubism.

Out of these discussions emerged the Section d'Or (Golden Section) group, which organized a major exhibition at the Galerie La Boétie in Paris in October 1912. This exhibition aimed to showcase the breadth and diversity of Cubist tendencies. Marcoussis exhibited alongside prominent artists such as Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger (who co-authored the first major treatise on Cubism, Du "Cubisme", that same year), Fernand Léger, Francis Picabia, Juan Gris, and the Delaunays (Robert and Sonia). The Section d'Or represented a significant moment in consolidating Cubism as a major avant-garde movement, and Marcoussis's participation solidified his position within its ranks. His friendships, particularly with Apollinaire, placed him at the heart of the intellectual and artistic debates shaping modern art.

Master of the Line: Marcoussis the Printmaker

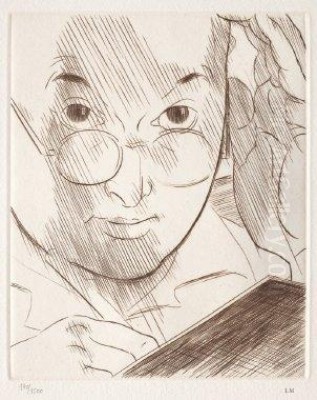

Beyond his significant contributions as a painter, Louis Marcoussis excelled in the art of printmaking, particularly etching and drypoint. He developed a remarkable technical proficiency, using line not just to define form but also to create texture, tone, and atmosphere. Printmaking offered artists a different medium for exploration and a means to disseminate their work more widely than unique paintings allowed.

His skill as an engraver led to important collaborations. He created illustrations for books by avant-garde writers, including providing etchings for Tristan Tzara's Indicateurs du cheminement des cœurs. Tzara, a key figure in the Dada movement and later associated with Surrealism, represented the cross-pollination occurring between different artistic and literary circles in Paris. Marcoussis's ability to translate his Cubist sensibility into the linear medium of etching made his prints highly sought after.

One of his most notable collaborations occurred later in his career, during the 1930s. He formed a close friendship with the Spanish Surrealist painter Joan Miró. At a time when Miró was exploring new techniques, Marcoussis generously shared his expertise in etching. He taught Miró the intricacies of the process, an encounter that proved highly fruitful for the Spanish artist. Miró's powerful Black and Red Series of etchings from 1938 was created during this period of mentorship and exchange, demonstrating the direct impact of Marcoussis's guidance. Marcoussis's own prints, such as his sensitive Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire or various Cubist still lifes like Still Life with Knife, stand as testaments to his mastery of the medium.

Personal Life, War, and Displacement

Marcoussis's personal life was deeply intertwined with his artistic journey. In 1913, he married Alice Halicka, a fellow painter also originally from Poland (Kraków). Alice was an accomplished artist in her own right, associated with the École de Paris, and their partnership was both personal and professional. They became French citizens, fully embracing their adopted homeland. Their daughter, Madeleine (Malène or Marlène), was born in 1922.

The outbreak of World War I dramatically interrupted artistic life in Paris. Marcoussis, despite being a foreign national initially, chose to serve his adopted country. He joined the French Foreign Legion, a path taken by several foreign-born artists and intellectuals. His service was distinguished, and he was awarded the Croix de Guerre for his bravery. This wartime experience undoubtedly marked him, adding another layer to his life story beyond the studio and salon.

The interwar years saw Marcoussis continue to develop his art, exhibiting internationally and solidifying his reputation. However, the looming shadow of another conflict brought profound disruption. With the Nazi invasion of France and the occupation of Paris in 1940, Marcoussis and Alice Halicka, being of Jewish descent (though sources vary on their degree of religious practice, their Polish origins made them vulnerable under Nazi racial laws), were forced to flee the capital. They sought refuge in Cusset, a town near Vichy in the unoccupied zone of southern France. It was here, in exile from the city that had defined his artistic life, that Louis Marcoussis passed away on October 22, 1941, at the age of 63 (based on the 1878 birth year). Alice Halicka survived the war and lived until 1975, playing a crucial role in preserving and promoting her husband's artistic legacy.

Later Works and Stylistic Evolution

Following World War I, Marcoussis's art continued to evolve, though he remained fundamentally connected to the principles of Cubism. His style perhaps became somewhat more synthesized, integrating Cubist structure with a greater degree of representation or decorative elements at times. He held his first major solo exhibition in Paris in 1925, a milestone that confirmed his standing in the art world.

His subject matter remained diverse. He continued to explore still life, a genre perfectly suited to Cubist analysis, but also produced portraits and landscapes. His depictions of the Brittany coast reveal a different facet of his work, applying his structural sensibility to the natural world. Works like The Seine and the Eiffel Tower (1925) show his engagement with Parisian iconography, rendered through a modernist lens. Later pieces, such as The Death of Nerval (1931) and Sleeping Beauty (1937), might suggest subtle influences from Surrealism, perhaps reflecting his connections with figures like Tzara and Miró, blending narrative or dreamlike elements with his established style. Throughout the 1920s and 30s, he remained an active participant in the international art scene.

Legacy and Historical Position

Louis Marcoussis occupies a significant place in the history of 20th-century art. He was undeniably a pioneer of Cubism, actively participating in its development and dissemination, particularly through his involvement with the Section d'Or group. While his name might not possess the immediate, universal recognition of Picasso, Braque, or Léger, his contribution was substantial and unique. Art historians recognize him as a key figure who helped shape the broader Cubist movement beyond its initial inventors.

His specific interpretation of Cubism, often characterized by a refined sense of composition and sometimes a greater chromatic subtlety or decorative inclination compared to the starkness of early Analytical Cubism, offers a valuable counterpoint within the movement. Furthermore, his exceptional skill as a printmaker sets him apart. His mastery of etching and drypoint was influential, impacting artists like Joan Miró and contributing significantly to the elevation of printmaking as a major avant-garde medium.

Artistically, he navigated a path from Impressionism through the core of Cubism, engaging with figures from Dada and Surrealism along the way. His relationships – friendships, collaborations, and likely the inherent competitiveness of the Parisian art scene – with contemporaries like Picasso, Braque, Gris, Apollinaire, Metzinger, Gleizes, Léger, Picabia, Delaunay, Miró, Tzara, La Fresnaye, Lotiron, and his wife Alice Halicka, paint a picture of a deeply embedded and active participant in the avant-garde. His works are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the Tate Modern in London, ensuring his continued visibility.

Conclusion

Louis Marcoussis's journey from Ludwig Markus of Warsaw to a respected member of the Parisian avant-garde encapsulates a remarkable story of artistic dedication and adaptation. He embraced the revolutionary potential of Cubism, contributing his distinct voice to its complex chorus. As both a painter and a printmaker of exceptional talent, he explored the fragmentation and reconstruction of reality, leaving behind a body of work characterized by structural rigor and often a subtle elegance. His collaborations, particularly his mentorship role with Joan Miró in etching, highlight his technical mastery and generosity. Though his life was cut short during the turmoil of World War II, Louis Marcoussis's art endures as a vital part of the Cubist legacy and the broader narrative of modern European art.