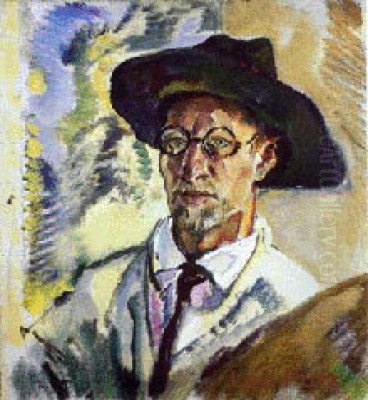

Leo Putz stands as a significant figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century European art. Born in the historically complex region of South Tyrol, then part of Austria-Hungary, Putz navigated the shifting currents of artistic movements, primarily establishing his career in Germany before finding new inspiration and facing political adversity that led him across continents. His work, characterized by a vibrant engagement with light and color, bridges Art Nouveau sensibilities, Impressionist techniques, and the burgeoning energy of early Expressionism, leaving a legacy marked by technical skill, thematic exploration, and resilience in the face of historical turmoil.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Leo Putz was born on June 18, 1869, in Merano, a town nestled in South Tyrol, which at the time belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. This region, with its unique blend of Germanic and Italian influences, perhaps subtly informed the cosmopolitan nature of his later life and career. Showing artistic promise from a young age, his formal training began relatively early. By the age of 16, around 1885, he was enrolled at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Munich (Akademie der Bildenden Künste München).

Munich, at this time, was a major European art center, rivaling Paris in its vibrancy and the progressive spirit of its artistic community. At the Academy, Putz initially studied under the history painter Gabriel von Hackl, known for his rigorous academic approach. He also received instruction from Robert Pötzlberger. This foundational training provided him with the essential skills in drawing and composition that would underpin his later, more experimental work.

Seeking broader horizons and exposure to different artistic currents, Putz, reportedly encouraged by his father, moved to Paris in 1889. He enrolled at the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that attracted students from around the world and served as a more liberal alternative to the official École des Beaux-Arts. In Paris, he studied under prominent academic painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant. While their style was rooted in academic tradition, the atmosphere of Paris itself was electric with innovation.

During his time in Paris (roughly 1889-1891), Putz inevitably encountered the revolutionary works of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. The emphasis on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light, and the use of pure color, as seen in the works of artists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, left a lasting impression. The bold compositions and symbolic color usage of Paul Gauguin also likely resonated with the young artist, steering him away from purely academic constraints towards more modern forms of expression. This Parisian sojourn was crucial in shaping his artistic direction, fostering an interest in contemporary themes and techniques.

Munich Secession and Die Scholle

Upon returning to Munich around 1892, Leo Putz found the city's art scene in a state of flux. Dissatisfaction with the conservative establishment of the official artists' association (Münchner Künstlergenossenschaft) and its dominance over major exhibitions led to a significant breakaway movement. Putz became involved early on with the formation of the Munich Secession, officially founded in 1892. This group, which included leading figures like Franz von Stuck, Wilhelm Trübner, and later Lovis Corinth, aimed to promote artistic freedom, higher quality exhibitions, and greater openness to international modern art trends, particularly Impressionism and Symbolism.

Putz's involvement with the Secession placed him firmly within the progressive wing of Munich's art world. He actively participated in their exhibitions, gaining visibility and recognition. His alignment with the Secession signaled his rejection of outdated academicism and his commitment to exploring more contemporary artistic languages.

Furthering his association with avant-garde circles, Putz became a key figure in the artists' association known as "Die Scholle" (The Clod or The Soil), founded in 1899. This group, which included artists like Fritz Erler, Walter Georgi, and Adolf Münzer, represented a younger generation emerging from the spirit of the Secession. While not adhering to a single unified style, the members of Die Scholle shared an interest in decorative qualities, often influenced by Art Nouveau (Jugendstil in German), and a focus on modern life and landscape, rendered with bold compositions and expressive color. They sought an art rooted in local character yet modern in spirit.

Putz's work during this period often appeared in the influential art and literary magazine Jugend, which gave its name to the Jugendstil movement. His contributions, alongside those of other Scholle members, helped define the visual identity of the magazine and the broader movement. He opened his own studio in Munich in 1897, establishing himself as an independent artist. His association with Die Scholle lasted until around 1905-1906, marking a significant phase where his style solidified, blending decorative elegance with an increasingly impressionistic handling of light and paint.

Mature Style: Impressionism and Beyond

Through the early years of the 20th century, Leo Putz developed a distinctive artistic voice. While grounded in the observational principles of Impressionism, particularly its German variant championed by artists like Max Liebermann and Max Slevogt, Putz's style retained a decorative sensibility likely influenced by Jugendstil and his work with Die Scholle. His primary focus shifted towards plein-air (open-air) painting, where capturing the transient effects of natural light became paramount.

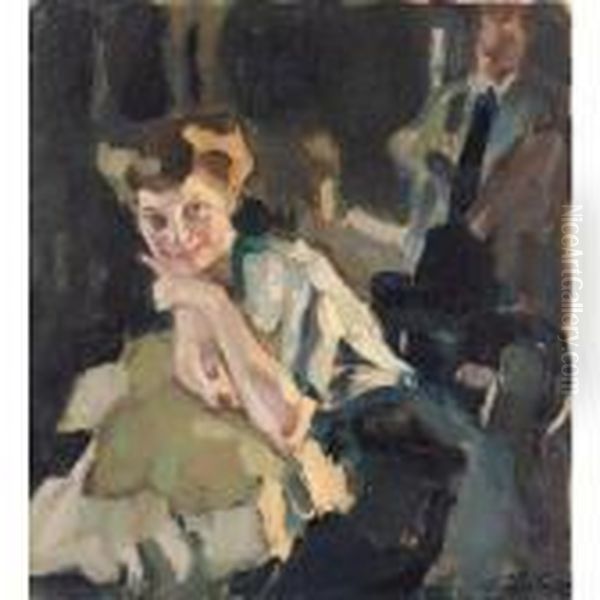

His brushwork grew looser and more dynamic, applying paint in vibrant strokes that conveyed energy and immediacy. Color became a key expressive tool, often heightened beyond strict naturalism to enhance the mood and visual impact of the scene. Putz demonstrated a remarkable ability to render the play of sunlight and shadow, particularly on water and the human form, which became central themes in his oeuvre.

Figures, landscapes, and especially the female nude in natural settings dominated his subject matter. His depictions of women were often elegant and sensuous, avoiding academic stiffness in favor of portraying modern leisure and a harmonious relationship between humanity and nature. These works resonated with audiences, and by 1903, his paintings were acquired by major institutions like the Dresden State Art Collections (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden) and the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, signaling significant official recognition.

His style during this mature phase is often characterized as a form of decorative Impressionism, sometimes bordering on early Expressionism due to its emotional intensity and bold technique. He masterfully balanced careful observation with subjective interpretation, creating works that were both visually appealing and emotionally engaging. This period laid the groundwork for some of his most celebrated series.

The Hartmannsberg Period

One of the most iconic and productive phases of Leo Putz's career occurred between approximately 1909 and 1914, often referred to as the Hartmannsberg period. During these years, Putz frequently worked near Hartmannsberg Castle, located close to Lake Chiemsee in Upper Bavaria. This idyllic setting provided the backdrop for his famous series of paintings depicting women bathing and relaxing by the water, often featuring his wife, the painter Frieda Blell, as a model.

These works, including the renowned Bathers (Badende) and Boat Pictures (Kahnbilder) series, epitomize Putz's mastery of light, color, and composition. He captured the dazzling effects of sunlight filtering through leaves, reflecting off the water's surface, and dappling across the skin of his subjects. The paintings exude a sense of carefree leisure, intimacy, and harmony with nature, characteristic of the era's fascination with outdoor life and a certain Arcadian ideal.

The brushwork in the Hartmannsberg paintings is particularly vibrant and energetic, applied in bold strokes and patches of pure color that seem to shimmer and dissolve forms in the bright light. Putz employed a high-keyed palette, using blues, greens, yellows, and whites to convey the brilliance of summer days. While clearly indebted to French Impressionism, these works possess a distinctly German character, perhaps more robust in form and sometimes imbued with a subtle decorative patterning reminiscent of his earlier Jugendstil associations.

The Hartmannsberg series cemented Putz's reputation as a leading figure in South German plein-air painting and Impressionism. These works remain highly sought after and are considered among his most significant contributions to the art of the period, showcasing his unique ability to blend sensuous subject matter with technical brilliance in capturing atmospheric effects.

Brazilian Years

In 1929, seeking new horizons and perhaps escaping the increasingly tense political climate in Germany, Leo Putz embarked on a significant journey, emigrating with his family to Brazil. This move marked a distinct chapter in his life and art. He initially settled in Rio de Janeiro, where his reputation preceded him, leading to an appointment as a professor at the National School of Fine Arts (Escola Nacional de Belas Artes).

Brazil's vibrant culture and dramatic tropical environment had a profound impact on Putz's work. The intense luminosity of the equatorial light, the exotic flora and fauna, and the diverse population offered fresh subjects and challenges. His palette, already bright, seemed to intensify further, embracing the saturated colors of the tropics. He painted numerous landscapes capturing the lush vegetation and coastal scenery, as well as portraits and genre scenes depicting local life.

Putz became involved with the Brazilian art scene, notably associating with the Sociedade Pró-Arte (Pro Arte Society) in Rio. He headed its painting department and exhibited extensively, including a significant showing of 57 works at the Pro Arte Salon in 1931. These works were also featured in the "Salão Revolucionário" (Revolutionary Salon) in Rio, an important event that showcased modernist tendencies alongside more established artists.

His presence in Brazil was not without controversy. His appointment at the National School of Fine Arts faced resistance from nationalist factions who were wary of foreign influence, particularly from European modernism which Putz represented to some extent. While his style was rooted in Impressionism and early Expressionism, it differed from the emerging directions of Brazilian modernism being forged by artists like Candido Portinari and Tarsila do Amaral. Nevertheless, Putz interacted with key figures, including landscape architect and artist Roberto Burle Marx.

Despite some friction, Putz's time in Brazil (1929-1933) was artistically fruitful and contributed to the dialogue around modern art in the country. His teaching influenced a generation of students, and his paintings from this period offer a unique European perspective on the Brazilian landscape and culture, characterized by vibrant color and dynamic light effects. He traveled within the country, painting in São Paulo and Minas Gerais, further enriching his South American experience.

Confrontation with Nazism and Exile

Leo Putz's return to Germany from Brazil in April 1933 coincided with the consolidation of power by the Nazi Party. As an artist associated with modern movements like Impressionism and Expressionism, and known for his depictions of nudes, Putz quickly fell afoul of the Nazi regime's repressive cultural policies. His art, which celebrated individual expression and sensuousness, was antithetical to the state-sanctioned heroic realism.

Furthermore, Putz was known to be critical of National Socialism. Consequently, his work was labeled "degenerate art" (Entartete Kunst), a term used by the Nazis to condemn virtually all modern art. Artists deemed "degenerate" faced persecution, were forbidden to exhibit or sell their work, and many were dismissed from teaching positions. Putz's paintings were removed from German museums.

In 1936 or 1937 (sources vary slightly on the exact date), Leo Putz was officially banned from working and painting in Germany by the Reich Chamber of Culture (Reichskulturkammer). This professional ban effectively ended his career within the country he had long considered his artistic home. Facing persecution and unable to practice his profession, Putz was forced into exile.

He initially sought refuge elsewhere, possibly spending time in Switzerland. Ultimately, he returned to his birthplace, Merano, in South Tyrol, which by then had become part of Italy under the Fascist regime of Mussolini, an ally of Nazi Germany. While perhaps offering a degree of separation from direct Nazi control in Berlin, the political climate in South Tyrol was also complex and increasingly oppressive, especially for those perceived as opponents of the Axis powers. His exile marked a period of profound difficulty and displacement.

Later Years and Death

The final years of Leo Putz's life were spent in his native South Tyrol, primarily in and around Merano. Living under the shadow of the Nazi regime in Germany and Fascism in Italy, and burdened by the professional ban imposed upon him, his circumstances were constrained. Reports suggest that even in Merano, he faced scrutiny and condemnation for his anti-Nazi sentiments.

Despite these hardships, Putz continued to paint, turning his attention to the landscapes and architecture of his homeland. He depicted the castles, villages, and rugged mountain scenery of South Tyrol. While perhaps lacking the exuberant freedom of his earlier plein-air work or the exoticism of his Brazilian paintings, these later works possess a quiet dignity and reflect his enduring connection to the act of painting itself. They represent the output of an artist working in relative isolation, finding solace and subject matter in his immediate surroundings.

Leo Putz passed away in Merano on July 21, 1940, at the age of 71. He died before the end of World War II and thus did not witness the fall of the regimes that had persecuted him or the post-war rehabilitation of modern art. His death occurred during a dark period in European history, cutting short a career that had spanned significant artistic and political transformations.

Artistic Legacy and Influence

Leo Putz left behind a rich and varied body of work that secures his place as an important artist of his generation. His primary contribution lies in his masterful handling of light and color, particularly within the context of German Impressionism and its transition towards Expressionism. He excelled at plein-air painting, capturing the vibrancy of outdoor scenes with a distinctive blend of observational accuracy and decorative flair. His depictions of the female nude, especially in the Hartmannsberg series, are celebrated for their sensuousness and integration within sun-drenched natural settings.

His time in Brazil added a unique dimension to his oeuvre, demonstrating his adaptability and his engagement with different cultural and environmental contexts. Through his teaching at the National School of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro, he exerted a direct influence on Brazilian artists, contributing to the development of modern art in South America, even if his style remained distinct from the dominant local trends. His friendship and artistic dialogue with fellow painters like the American expatriate Edward Cucuel, who also worked in Bavaria, further highlight his connections within the international art community of the time.

The persecution Putz suffered under the Nazi regime underscores the political dimension of art in the 20th century. His classification as a "degenerate artist" paradoxically affirms his significance as a representative of the modern spirit that the Nazis sought to suppress. After World War II, his work gradually regained recognition, and he is now acknowledged as a key figure bridging late Impressionism and early Expressionism in Germany.

Today, Leo Putz's paintings are held in numerous public and private collections across Europe and the Americas, including the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, the Lenbachhaus in Munich, the Albertina in Vienna, and the National Museum of Fine Arts (Museu Nacional de Belas Artes) in Rio de Janeiro. His works continue to be appreciated on the art market, testament to their enduring appeal and historical importance. He remains admired for his technical skill, his vibrant aesthetic, and his dedication to his art throughout a life marked by both artistic triumph and profound adversity.

Contemporaries and Connections

Leo Putz's long and varied career placed him in contact with a wide array of artists across different movements and countries. In Munich, his early involvement with the Secession connected him to its leading figures like Franz von Stuck and Lovis Corinth. His central role in "Die Scholle" fostered close collaboration with Fritz Erler, Walter Georgi, and Adolf Münzer. As a prominent figure in German Impressionism, his work can be seen in dialogue with that of Max Liebermann, Max Slevogt, and Wilhelm Trübner.

His time in Paris exposed him to the foundational works of Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Paul Gauguin, whose innovations profoundly impacted his development. Later, his friendship with the American Impressionist Edward Cucuel in Bavaria highlights the international network of artists working in the region.

In Brazil, Putz engaged with the local art scene, teaching at the national academy and exhibiting alongside emerging modernists. While his style differed from key figures of Brazilian Modernism like Candido Portinari, Tarsila do Amaral, or Emiliano Di Cavalcanti, his presence contributed to the artistic discourse. He formed connections with figures like Roberto Burle Marx. His position sometimes put him in contrast with more conservative or nationalist elements within the Brazilian art establishment. The breadth of these connections underscores Putz's position within the dynamic and often turbulent art world of the early 20th century.

Conclusion

Leo Putz emerges from the historical record as a versatile and resilient artist whose life and work reflect the major artistic and political currents of his time. From his Tyrolean roots and academic training in Munich and Paris, he embraced the light-filled canvases of Impressionism, infused with the decorative elegance of Jugendstil. His celebrated Hartmannsberg period captured an idyllic vision of nature and leisure, while his years in Brazil demonstrated his capacity for adaptation and engagement with new environments. His confrontation with Nazism and subsequent exile tragically highlight the vulnerability of art and artists under totalitarian regimes. Despite these challenges, Putz continued to create, leaving a legacy characterized by vibrant color, masterful light effects, and a deep appreciation for the beauty of the natural world and the human form. He remains a significant figure, bridging artistic movements and continents, whose work continues to captivate viewers today.