Ludwig von Hofmann stands as a significant figure in German art history, a painter, graphic artist, and designer whose career spanned the dynamic transition from the 19th to the 20th century. Active from the late 1880s until his death in 1945, Hofmann navigated the currents of Symbolism, Art Nouveau (known as Jugendstil in Germany), and the nascent stirrings of modernism. His work is characterized by an enduring fascination with the harmony between humanity and nature, often depicted through idyllic, Arcadian landscapes populated by graceful, often nude figures. He was not merely a studio artist but also an influential teacher and a key participant in seminal art movements that shaped the course of German art.

Hofmann's legacy is complex, marked by early acclaim, association with progressive art groups, a significant teaching career, and the later shadow of having some works condemned as "degenerate" by the Nazi regime. Yet, his unique blend of classical idealism, decorative sensibility, and modern psychological undertones continues to resonate. This exploration delves into the life, work, influences, and enduring impact of Ludwig von Hofmann, an artist who sought beauty and harmony in a rapidly changing world.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Ludwig Hofmann was born in Darmstadt, Grand Duchy of Hesse, on August 17, 1861. His background was one of privilege and political prominence; his father, Karl von Hofmann, was a significant Prussian statesman who served as Minister President of Hesse and later headed the Reich Chancellery under Bismarck. This connection to the upper echelons of society likely provided Ludwig with both cultural exposure and the means to pursue an artistic career, although he initially considered other paths.

His formal artistic training began relatively late, in 1883, when he enrolled at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. Seeking different instruction, he soon moved to the Academy of Fine Arts in Karlsruhe. There, he studied under the history painter Ferdinand Keller, known for his large-scale historical and allegorical compositions. This academic grounding provided him with technical proficiency, but Hofmann's artistic inclinations soon led him towards more contemporary influences.

A pivotal moment in his education came in 1889 when he traveled to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the time. He enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school favored by many foreign students and those seeking an alternative to the rigid École des Beaux-Arts. This period exposed him directly to the latest currents in French art, particularly Symbolism and Post-Impressionism, which would profoundly shape his artistic vision.

The Influence of Paris and Early Success

The year spent at the Académie Julian was transformative for Hofmann. In Paris, he absorbed the prevailing artistic atmosphere and came under the influence of key figures. He particularly admired the work of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, whose large-scale murals, simplified forms, muted colors, and idealized, allegorical figures resonated deeply with Hofmann's own developing aesthetic. The sense of timelessness and serene classicism in Puvis's work left a lasting impression.

Another significant influence was Paul-Albert Besnard, a painter known for his vibrant use of color and light, often blending academic technique with Impressionist sensibilities. Besnard's approach to capturing atmosphere and his more modern palette likely encouraged Hofmann to move beyond the darker tones often favored in German academic painting. The exposure to these artists, along with the broader Symbolist movement gaining traction in Paris, solidified Hofmann's interest in subjective experience, mood, and decorative composition over strict naturalism.

Upon returning to Germany, Hofmann initially settled in Berlin, which was rapidly becoming a major cultural hub. His experiences in Paris equipped him with a fresh perspective, and his work began to attract attention. He started developing his characteristic style, focusing on themes of youth, nature, and idyllic harmony, often rendered with flowing lines and a bright, sometimes non-naturalistic palette that distinguished him from many of his German contemporaries.

Berlin: Die XI and the Secession

Berlin in the 1890s was a city brimming with artistic energy and debate. The established art institutions, particularly the Association of Berlin Artists and the official annual Salon (Große Berliner Kunstausstellung), were dominated by conservative tastes favored by the Kaiser. Younger, more progressive artists found it difficult to exhibit their work and gain recognition. This led to the formation of alternative groups seeking artistic independence.

In 1892, Ludwig von Hofmann became a founding member of the "Vereinigung der XI" (Association of the Eleven). This group, which included prominent artists like Max Liebermann, Walter Leistikow, and Max Klinger, aimed to organize independent exhibitions showcasing more modern and experimental art, breaking away from the constraints of the official Salon. Hofmann's participation placed him firmly within the avant-garde circles of Berlin.

The activities of Die XI paved the way for a larger and more impactful movement. In 1898, frustrated by the continued conservatism of the establishment, many members of Die XI, including Hofmann, Liebermann, and Leistikow, spearheaded the formation of the Berlin Secession. This group represented a definitive break (or "secession") from the official art scene. The Berlin Secession quickly became the most important forum for modern art in Germany, exhibiting not only German Impressionism and Jugendstil but also works by international artists like Edvard Munch, Auguste Rodin, and the French Impressionists. Hofmann was an active participant in the Secession's exhibitions, solidifying his reputation as a leading modern artist.

Symbolism and the Arcadian Ideal

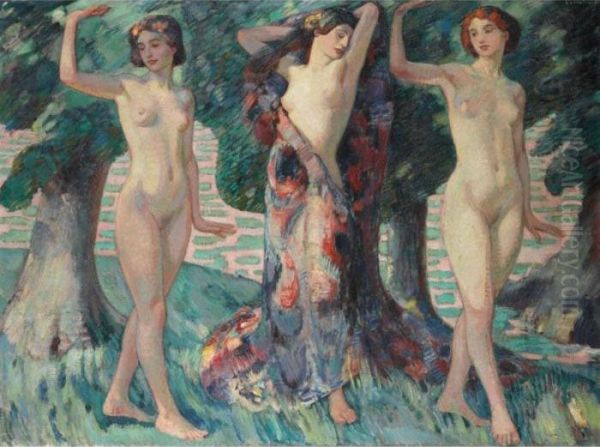

At the heart of Ludwig von Hofmann's artistic output lies a deep engagement with Symbolism and a persistent vision of an Arcadian ideal. Rejecting the mere imitation of reality, Symbolist artists sought to express inner truths, emotions, and ideas through suggestive imagery, metaphors, and symbolic motifs. Hofmann embraced this approach, using landscape and the human figure not just for their descriptive qualities but for their evocative potential.

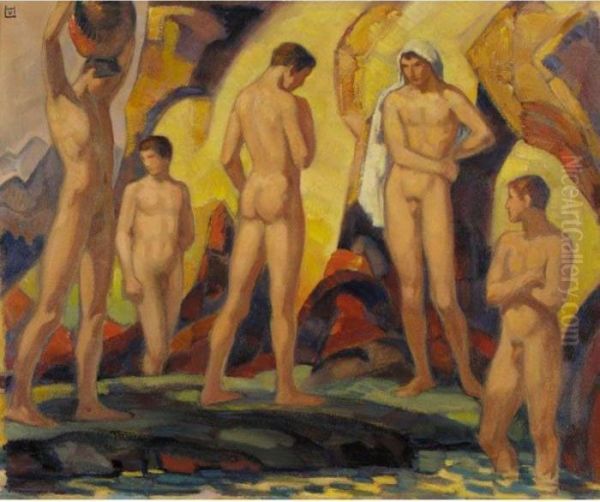

His most characteristic works depict idyllic, sun-drenched landscapes, often populated by nude or semi-nude youths dancing, resting, or interacting harmoniously with nature. These scenes evoke a sense of timeless paradise, a modern Arcadia drawing inspiration from classical antiquity, particularly ancient Greece, but infused with a distinctly turn-of-the-century sensibility. The figures are typically idealized, embodying youth, beauty, and a state of natural innocence, often rendered with flowing, rhythmic lines characteristic of Jugendstil.

This focus on the body beautiful in nature connected with broader cultural trends of the time, including the Lebensreform (Life Reform) movement, which advocated for natural living, physical health, and a return to simpler ways of life as an antidote to rapid industrialization and urbanization. Hofmann's paintings offered a vision of liberation, sensuality, and spiritual connection with the natural world, resonating with contemporaries seeking escape and renewal. Influences like the Swiss Symbolist Arnold Böcklin, with his mythological landscapes, and the classicizing figures of Hans von Marées can also be discerned in Hofmann's thematic concerns.

Masterworks: Capturing Light and Movement

Several key paintings exemplify Hofmann's mature style and thematic preoccupations. Frühlingsstürme (Spring Storms), created around 1894-95, is one of his most celebrated works. It depicts a group of dynamic, windswept figures, mostly male youths, running joyfully through a vibrant, stylized landscape under a dramatic sky. The painting captures a sense of elemental energy, youthful exuberance, and the vital forces of nature. The flowing lines, bold color contrasts, and rhythmic composition are hallmarks of his Jugendstil-inflected Symbolism. This painting's frame later became a subject of conservation debate after the original was lost and the painting recovered post-WWII.

Another significant work is Leben (Life), which explores the cycle of existence within an Arcadian setting. It often features figures representing different stages or aspects of life, integrated into a lush, idealized natural environment. These works reflect on themes of nature, growth, and the human condition, blending classical allegory with a modern sense of psychological depth and decorative beauty. The emphasis is on harmony and the interconnectedness of all living things.

Notturno (Nocturne) showcases a different mood, often depicting figures in twilight or moonlit landscapes. These works explore themes of reverie, introspection, and the romantic or mysterious aspects of nature. The interplay of light and shadow, combined with the serene or melancholic poses of the figures, creates a powerful atmosphere. Through works like these, Hofmann demonstrated his ability to manipulate color, light, and composition to evoke specific emotional and symbolic resonances, moving beyond simple representation towards a more poetic and subjective vision.

The Weimar Years: Art Education and Reform

In 1903, Hofmann's reputation led to his appointment as a professor at the Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstschule Weimar (Grand Ducal Saxon Art School Weimar). This move marked a significant phase in his career, placing him at the center of ambitious art reform efforts. The Weimar school, under the patronage of Grand Duke Wilhelm Ernst and the directorship of Henry van de Velde (from 1902), was envisioned as a hub for the "Neue Weimar" (New Weimar) movement, aiming to revitalize the arts and crafts by bridging the gap between fine art and applied design – a concept that would later be central to the Bauhaus, which emerged from the same institution.

Hofmann's appointment was part of this progressive agenda. He taught alongside other forward-thinking artists and designers, contributing to an environment that fostered experimentation and a modern approach to art education. His own work, with its strong decorative qualities and integration of figure and landscape, aligned well with the school's aims. During his time in Weimar (until 1916), he continued to produce significant paintings and graphic works.

He also formed important connections, notably with Count Harry Kessler, a prominent diplomat, patron, publisher, and collector who was a key figure in promoting modern art and literature in Weimar and beyond. Kessler commissioned work from Hofmann and included him in his influential circle. Hofmann's role as an educator was also impactful; he mentored a generation of students, including notable figures like the Dadaist and Surrealist pioneer Hans (Jean) Arp and the painter Ivo Hauptmann (son of the playwright Gerhart Hauptmann). His teaching likely emphasized drawing, composition, and the expressive use of color, grounded in his own artistic practice. The sculptor Gerhard Marcks was also active in Weimar during related periods, contributing to the vibrant artistic milieu.

Graphic Arts and Design: The Pan Connection

Beyond his paintings, Ludwig von Hofmann made significant contributions as a graphic artist and designer. His facility with line and decorative composition translated effectively into printmaking and illustration. He produced numerous etchings, lithographs, and drawings that explored similar themes to his paintings – Arcadian idylls, mythological subjects, and the harmonious human form in nature. His graphic works often possess a particular immediacy and fluidity.

His involvement with the influential art and literary journal Pan was particularly important. Launched in Berlin in 1895, Pan was a lavishly produced magazine dedicated to promoting modern art, literature, and design, becoming a key vehicle for the dissemination of Jugendstil aesthetics. Hofmann was a regular contributor, creating illustrations, vignettes, and decorative elements for the journal. His work appeared alongside contributions from major European artists and writers, including Max Klinger, Otto Eckmann, Franz von Stuck, and international figures like Auguste Rodin and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

His contributions to Pan helped solidify his reputation and spread his distinctive style. The magazine's emphasis on the integration of art into all aspects of life, including print media, aligned perfectly with Hofmann's own decorative sensibilities and the broader aims of the Jugendstil movement. His graphic work is characterized by elegant linearity, rhythmic patterns, and a sophisticated sense of design, making a lasting contribution to German graphic arts at the turn of the century.

Dresden Professorship and Later Career

In 1916, during World War I, Ludwig von Hofmann left Weimar to take up a prestigious professorship at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, succeeding Gotthardt Kuehl. Dresden, with its rich artistic traditions and renowned collections, offered a different environment from Weimar. Hofmann continued his teaching career there for over two decades, remaining an influential figure in art education until his retirement, likely around 1931, though sources sometimes state he taught until 1937.

His artistic style continued to evolve, though he remained largely committed to his core themes of idealized nature and the human form. While the avant-garde moved towards Expressionism, Cubism, and abstraction, Hofmann maintained his connection to Symbolism and Jugendstil, albeit perhaps with subtle shifts in palette or composition. His work retained its characteristic grace, decorative quality, and emphasis on harmony.

His continued standing is evidenced by his participation in the art competition at the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam. These competitions, held between 1912 and 1948, were part of Baron Pierre de Coubertin's original vision for the modern Olympics, awarding medals for works inspired by sport. Hofmann's inclusion suggests his work was still held in high regard within certain established art circles, even as newer, more radical art movements gained prominence. He remained a respected, if increasingly less avant-garde, figure in the German art world leading into the tumultuous 1930s.

Navigating the Nazi Era: "Degenerate Art"

The rise of the Nazi Party to power in 1933 brought about a dramatic and oppressive shift in the cultural landscape of Germany. The regime promoted a narrow, state-approved aesthetic based on conservative, pseudo-classical, and nationalistic ideals, while aggressively condemning most forms of modern art as "Entartete Kunst" – Degenerate Art. This included Expressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, Dada, and even aspects of Impressionism and Symbolism that did not align with Nazi ideology.

Ludwig von Hofmann, despite his earlier establishment success and professorships, did not escape censure. In 1937, as part of the infamous Degenerate Art campaign, several of his works were confiscated from German museums. The exact reasons for targeting Hofmann might have varied; perhaps the sensuality of his nudes, the perceived lack of heroic nationalism, or simply his association with earlier "decadent" movements like Symbolism and Jugendstil were deemed unacceptable. Hundreds of artists saw their works removed, sold abroad, or destroyed during this period.

While Hofmann himself does not appear to have faced severe personal persecution compared to some other artists (perhaps due to his age or connections), the designation of his work as "degenerate" represented a significant blow to his reputation within Nazi Germany and led to the removal of his art from public view. This period cast a shadow over the later part of his life and contributed to a temporary decline in his visibility following World War II. The experience highlights the precarious position of artists under totalitarian regimes, where aesthetic judgments become politicized instruments of control.

Artistic Relationships: Teachers, Contemporaries, and Students

Ludwig von Hofmann's long career placed him in contact with a wide array of influential figures in the art world, shaping his development and defining his position within various movements. His primary teacher in Karlsruhe was Ferdinand Keller, grounding him in academic tradition. In Paris, the influence of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes and Paul-Albert Besnard was crucial in steering him towards Symbolism and a more modern use of color and form.

In Berlin, his association with the founders of Die XI and the Berlin Secession was paramount. He worked alongside major figures like Max Liebermann, the leading German Impressionist, and Walter Leistikow, known for his moody Brandenburg landscapes. Collaboration and shared purpose marked these relationships in their fight against academic conservatism. He also moved in circles that included Max Klinger, another key Symbolist known for his graphic cycles, and potentially had contact with figures associated with the Pan journal like Otto Eckmann.

His time in Weimar brought him into the orbit of Henry van de Velde, the Belgian Art Nouveau architect and designer, and the influential patron Count Harry Kessler. He admired the work of earlier Symbolists like Arnold Böcklin and the classicist Hans von Marées. As a teacher, he directly influenced the next generation, most notably Hans (Jean) Arp, who would become a central figure in Dada and Surrealism, and Ivo Hauptmann, who pursued a path closer to German Expressionism. The sculptor Gerhard Marcks was another important contemporary associated with the Weimar art scene and later the Bauhaus. These connections illustrate Hofmann's role as both a recipient and transmitter of artistic ideas across several decades.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

Ludwig von Hofmann died on June 23, 1945, in Pillnitz, near Dresden, shortly after the end of World War II. The immediate post-war period was chaotic, and much of his estate was reportedly at risk of confiscation by Soviet forces, though his widow managed to preserve a significant portion of his work. For a time, his art fell into relative obscurity, overshadowed by the more radical movements of the 20th century and perhaps tainted by the "degenerate" label, even after the fall of the Nazi regime.

However, from the later 20th century onwards, there has been a renewed appreciation for Symbolism and Jugendstil, leading to a re-evaluation of Hofmann's contributions. Art historians and curators began to recognize the quality, originality, and historical significance of his work. Exhibitions and publications have brought his paintings and graphic art back into the public eye, highlighting his unique synthesis of classical ideals, decorative aesthetics, and modern sensibilities.

His influence extended beyond the visual arts; his Arcadian visions resonated with literary figures like the writers Thomas Mann and Hugo von Hofmannsthal, who explored similar themes of beauty, sensuality, and the complexities of modern existence. Today, Ludwig von Hofmann is acknowledged as one of the leading German artists of his generation, a master of color and line who created a distinctive world of lyrical beauty and symbolic depth. His works are held in numerous museums in Germany and internationally, and because he died in 1945, his works are now in the public domain in many countries, allowing for wider dissemination and study.

Conclusion

Ludwig von Hofmann occupies a fascinating position in the narrative of modern art. He was an artist deeply rooted in the cultural aspirations and anxieties of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His work offers a compelling blend of tradition and innovation, drawing on classical mythology and academic training while embracing the decorative energy of Jugendstil and the introspective depth of Symbolism. He championed artistic freedom through his involvement in the Secession movements and dedicated much of his life to educating younger artists.

His vision of Arcadia, a world of harmonious integration between humanity and nature, rendered with vibrant color and elegant line, remains his most enduring legacy. While navigating the complexities of his time, including the oppressive cultural policies of the Nazi era, Hofmann remained largely true to his artistic ideals. Today, his paintings and graphic works are appreciated not just for their aesthetic appeal but also as significant documents of a pivotal era in European art history, embodying a search for beauty, harmony, and meaning in the face of profound societal change. He stands as a vital link between the idealism of the 19th century and the complex dawn of the modern age.