Leonardo Alenza y Nieto stands as a significant, if somewhat melancholic, figure in the landscape of 19th-century Spanish art. A painter and illustrator deeply rooted in the Romantic tradition, his work offers a poignant and often critical glimpse into the society of his time, particularly the bustling, multifaceted life of Madrid. Though his career was tragically short and marked by financial hardship, Alenza left behind a body of work that continues to resonate for its keen observation, psychological depth, and its distinct connection to the legacy of the great Spanish masters, most notably Francisco Goya.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

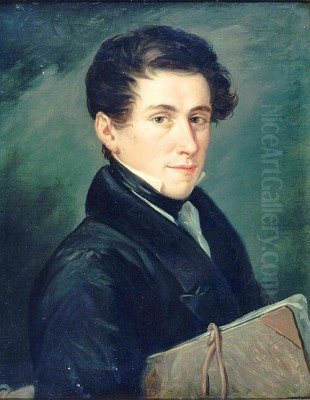

Born in Madrid on November 6, 1807, Leonardo Alenza y Nieto's early life was set against a backdrop of political turmoil and social change in Spain, following the Napoleonic Wars and the subsequent struggles between liberal and absolutist factions. His father, Valentín Alenza, was a government employee and a minor poet, which perhaps instilled in the young Leonardo an appreciation for the arts. His formal artistic training commenced at the prestigious Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid.

At the Academy, Alenza studied under influential figures of the time. His teachers included Juan Antonio de Ribera, a painter known for his historical subjects and portraits, who had himself trained in Paris with Jacques-Louis David, bringing a Neoclassical rigor to his teaching. Another key instructor was José de Madrazo, a dominant figure in Spanish Neoclassicism, director of the Prado Museum, and court painter. Despite being immersed in this Neoclassical academic environment, Alenza's artistic temperament would ultimately lean more towards the burgeoning Romantic movement and the gritty realism of everyday life.

This formal training provided him with a solid technical foundation in drawing and painting. However, like many artists of the Romantic era, Alenza seemed more drawn to personal expression and the depiction of contemporary reality than to the idealized subjects favored by Neoclassicism. His true artistic lineage would connect more profoundly with earlier Spanish masters who excelled in capturing the human condition.

The Prevailing Influence of Goya and Velázquez

It is impossible to discuss Leonardo Alenza y Nieto without acknowledging the profound impact of Francisco Goya. Alenza is often regarded as one of the last true inheritors of Goya's spirit, particularly his critical and satirical view of society, his interest in popular types, and his expressive, often somber, palette. Goya's series of etchings, such as Los Caprichos and The Disasters of War, with their unflinching look at human folly, superstition, and suffering, undoubtedly left a mark on Alenza's artistic consciousness. He absorbed Goya's ability to infuse genre scenes with deeper meaning and psychological insight.

Beyond Goya, the influence of Diego Velázquez, the 17th-century master of Spanish Golden Age painting, can also be discerned in Alenza's work. Velázquez's unparalleled ability to capture reality with truthfulness, his dignified portrayal of all subjects, from royalty to commoners, and his mastery of light and atmosphere, provided a lasting model for Spanish painters. Alenza's commitment to depicting the everyday life of Madrid with a sense of immediacy and authenticity echoes Velázquez's own observational prowess.

While these masters provided a strong foundation, Alenza was also a man of his time, absorbing the currents of European Romanticism. However, Spanish Romanticism had its own distinct characteristics, often intertwined with "Costumbrismo" – the depiction of local customs, traditions, and types, which became a popular genre in 19th-century Spain. Artists like Eugenio Lucas Velázquez (often stylistically compared to Alenza and also a follower of Goya), Valeriano Domínguez Bécquer, and his brother, the poet Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, were central to this movement, capturing the essence of Spanish regional life.

Artistic Style: Romanticism and Costumbrismo

Alenza's artistic style is firmly situated within Spanish Romanticism, but with a strong Costumbrista leaning. His Romanticism is not typically of the grandiose, historical, or overtly sentimental kind seen in some parts of Europe, such as the dramatic canvases of French Romantics like Théodore Géricault or Eugène Delacroix. Instead, Alenza's Romanticism is more intimate, focused on individual human experience, social commentary, and often imbued with a sense of melancholy or irony.

His color palette tended towards the somber, employing dark tones, ochres, browns, and grays, reminiscent of Goya's later works and the Spanish Baroque tradition exemplified by artists like Jusepe de Ribera and Francisco de Zurbarán. This use of chiaroscuro and a restrained palette often served to heighten the emotional intensity or the stark reality of his scenes. His brushwork could be loose and expressive, prioritizing emotional impact over meticulous finish, another trait shared with Goya.

Alenza excelled in capturing the "tipos populares" – the popular types – of Madrid: street vendors, beggars, artisans, soldiers, dandies, and figures from the city's underbelly. These were not merely picturesque representations; Alenza often imbued them with a sense of dignity, pathos, or a critical edge, reflecting the social realities of a city grappling with modernization and poverty. His work provides a valuable visual document of Madrid's social fabric during the mid-19th century.

Themes and Subject Matter: A Mirror to Madrid's Soul

The primary focus of Alenza's oeuvre was the daily life and social customs of Madrid. He was an acute observer of his urban environment, translating its myriad scenes into paintings and drawings that ranged from the anecdotal to the deeply satirical. His works often explored the contrasts and contradictions of society: poverty alongside aspiration, piety mixed with superstition, and the often-absurd realities of human behavior.

Social marginalization was a recurring theme. Alenza depicted those on the fringes of society with an empathetic yet unsentimental eye. His portrayals of beggars, street urchins, and struggling artisans highlight the economic hardships prevalent at the time. These works serve as a form of social commentary, subtly critiquing the societal conditions that led to such disparities.

Satire was another powerful tool in Alenza's artistic arsenal. He frequently lampooned social affectations, romantic excesses, and human vices. This satirical vein connects him directly to Goya's critical prints and paintings. Alenza's humor is often dark, tinged with an understanding of human frailty. He was particularly adept at capturing the theatricality of everyday life, the poses and pretenses people adopted.

His genre scenes, or "cuadros de costumbres," depicted a wide array of activities: tavern scenes, street brawls, popular festivals, domestic interiors, and encounters between various social types. These works are invaluable for their depiction of 19th-century Spanish customs, attire, and social interactions.

Key Works: Masterpieces of Observation and Satire

Several works stand out in Leonardo Alenza y Nieto's relatively small but impactful oeuvre, showcasing his distinct style and thematic concerns.

Perhaps his most famous painting is the Sátira del suicidio romántico (Satire on Romantic Suicide), painted around 1839. This iconic work, housed in the Museo Nacional del Romanticismo in Madrid, depicts a distraught young man, pistol in hand, contemplating suicide over a failed love affair, while his beloved lies seemingly dead or fainted beside him. The scene is melodramatic, almost theatrical, and Alenza uses it to gently mock the exaggerated emotionalism and morbid fascinations often associated with the Romantic movement. The dark, atmospheric setting and the expressive figures are characteristic of his style. It’s a complex piece, as Alenza himself was a product of Romanticism, making the satire perhaps partly self-reflective.

El Viático or La paliza (The Beating/The Viaticum), dated around 1835, is another powerful genre scene. It depicts a street fight, a common occurrence, rendered with a raw energy and a focus on the brutal reality of such an encounter. The dynamic composition and the expressive, almost grotesque, figures showcase Alenza's ability to capture movement and intense emotion.

Títeres en Galicia (Galician Puppets), also from around 1835, shows a crowd gathered around a puppet show, a popular form of entertainment. Alenza captures the varied reactions of the onlookers, from captivated children to indifferent adults, offering a snapshot of public leisure and popular culture.

El triunfo de David (The Triumph of David), dated 1842, is a more traditional subject, yet Alenza imbues it with his characteristic style. While it depicts a biblical scene, the focus remains on the human drama and the expressive qualities of the figures.

Other notable works include numerous portraits, which, while perhaps less innovative than his genre scenes, demonstrate his technical skill. He also painted scenes like El Torero y la Maja (The Bullfighter and the Flower Girl), which tapped into popular Spanish imagery and the romanticized figures of the bullfighting world and Madrid's vibrant female types, the "majas." These themes were also popular with Goya and later artists like Eugenio Lucas.

Alenza as an Illustrator

Beyond his paintings, Leonardo Alenza y Nieto was a prolific and talented illustrator. He contributed drawings and engravings to various publications, further showcasing his keen observational skills and satirical wit. His illustrations often accompanied literary works, bringing characters and scenes to life with a visual style that complemented the text.

Among his most significant illustrative projects were the drawings for editions of The Adventures of Gil Blas of Santillane, the picaresque novel by the French writer Alain-René Lesage. Alenza's illustrations captured the episodic nature and the social satire of the novel, finding a kindred spirit in its roguish protagonist and its depiction of a corrupt and varied society.

He also created illustrations for the works of the great Spanish Golden Age writer Francisco de Quevedo, known for his sharp satire and profound reflections on life and death. Alenza's style was well-suited to Quevedo's often dark and critical vision. These illustrative works demonstrate his versatility and his ability to adapt his art to different narrative forms, always maintaining his characteristic expressiveness. His work in this field places him in the company of other great 19th-century illustrators who brought literature to a wider audience through visual means.

The Weight of Poverty and a Shortened Life

Despite his talent and a certain degree of recognition within artistic circles – he did receive some commissions and exhibited his work – Leonardo Alenza y Nieto struggled with poverty throughout his life. The art market in Spain during this period was not always supportive of artists focusing on contemporary genre scenes, especially those with a critical edge. Official patronage often favored more academic or historically grand subjects, as championed by figures like Federico de Madrazo (son of José de Madrazo), who became a leading portraitist and a powerful figure in the Spanish art world.

Alenza's financial difficulties were compounded by ill health. He suffered from tuberculosis, a common and often fatal disease in the 19th century. His precarious health and lack of resources undoubtedly impacted his productivity and his ability to secure more lucrative commissions.

Tragically, Leonardo Alenza y Nieto died young, on June 30, 1845, at the age of just 37. His poverty was such that his funeral expenses had to be covered by his friends, a poignant testament to the difficult circumstances faced by many artists of the era. His early death cut short a promising career and left a void in the Spanish art scene. One can only speculate on how his art might have evolved had he lived longer.

Legacy and Collections

Despite his short life and limited output compared to some of his contemporaries, Leonardo Alenza y Nieto holds an important place in the history of Spanish art. He is recognized as a key figure in the transition from Goya's era to the later developments of 19th-century Spanish realism and genre painting. His work provides a vital link, carrying forward Goya's spirit of social observation and critique into a new generation.

His paintings and drawings are cherished for their authentic portrayal of 19th-century Madrid, offering invaluable insights into the city's social customs, types, and atmosphere. He captured a world that was rapidly changing, and his art serves as a historical document as much as an artistic statement. His influence can be seen in later Spanish painters who continued the Costumbrista tradition or focused on social realism.

Today, the most significant collections of Alenza's work are housed in major Spanish museums. The Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid holds a number of his paintings, allowing them to be seen in the context of the great Spanish masters who influenced him. The Museo Nacional del Romanticismo, also in Madrid, is another crucial repository, particularly for works like his Satire on Romantic Suicide, which perfectly encapsulates the spirit of the era it represents. Other Spanish museums and private collections also feature his works.

While perhaps not as internationally renowned as Goya or later Spanish masters like Joaquín Sorolla or Pablo Picasso, Leonardo Alenza y Nieto is a figure deeply appreciated by connoisseurs of Spanish art. His unique vision, his technical skill, and his poignant depiction of the human condition ensure his enduring relevance. He remains a testament to the power of art to reflect, critique, and immortalize the society from which it springs. His life, though marked by hardship, was dedicated to capturing the soul of his city and its people with honesty and a profound, often melancholic, understanding.