Introduction: A Bridge Between Eras

Eugenio Lucas Velázquez stands as a fascinating and pivotal figure in 19th-century Spanish art. Born in Madrid in 1817 and passing away in the same city in 1870, his life spanned a period of significant political and cultural change in Spain. Primarily recognized as a Romantic painter, Lucas Velázquez is inextricably linked to the towering legacy of Francisco Goya, whose style he deeply admired and often emulated. Yet, he was more than a mere imitator; he was an artist who absorbed the spirit of his predecessor and reinterpreted it through the lens of his own time, creating a body of work known for its dynamism, dramatic flair, and technical innovation. His art serves as a bridge, connecting the powerful expressiveness of Goya to later developments in Spanish painting.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Madrid

Eugenio Lucas Velázquez entered the world in Alcalá de Henares, near Madrid, though he is primarily associated with the capital city where his career unfolded. His formal artistic training began at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. While records suggest he studied alongside figures like the influential Neoclassical painter José de Madrazo, the specific impact of academic tutors seems less significant than his self-directed education. It appears Lucas Velázquez spent more formative time elsewhere, particularly within the hallowed halls of the Prado Museum.

The Prado became his true academy. There, he immersed himself in the works of Spain's Golden Age masters, most notably Diego Velázquez, whose command of realism and portraiture left an indelible mark on Spanish art. However, it was the museum's extensive collection of Francisco Goya's works that truly captivated the young artist. He dedicated countless hours to copying Goya's paintings and etchings, absorbing not just the technique but the very essence of Goya's dramatic, often dark, and profoundly human vision. This intense study laid the foundation for his entire artistic trajectory.

During these early years, Lucas Velázquez also formed connections with contemporary artists. His friendship with Genaro Pérez Villaamil, a leading Romantic landscape painter, is evidenced in some of his early landscape works, such as Rocky Landscape with Figures and Landscape with Fishermen. These pieces suggest a shared interest in the picturesque and the dramatic potential of nature, hinting at mutual influence and artistic dialogue between the two painters during their formative period in Madrid's vibrant art scene.

The Enduring Shadow of Goya

The influence of Francisco Goya on Eugenio Lucas Velázquez cannot be overstated; it is the defining characteristic of his artistic identity. He is widely regarded as one of Goya's most fervent and skilled followers, dedicating much of his career to exploring themes and stylistic approaches pioneered by the Aragonese master. Lucas Velázquez didn't just copy Goya; he internalized his spirit, particularly the dramatic intensity, the fascination with Spanish folklore and customs, and the exploration of the darker aspects of human experience.

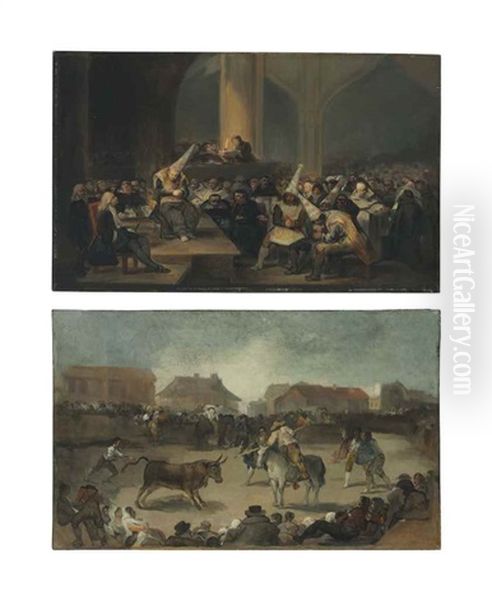

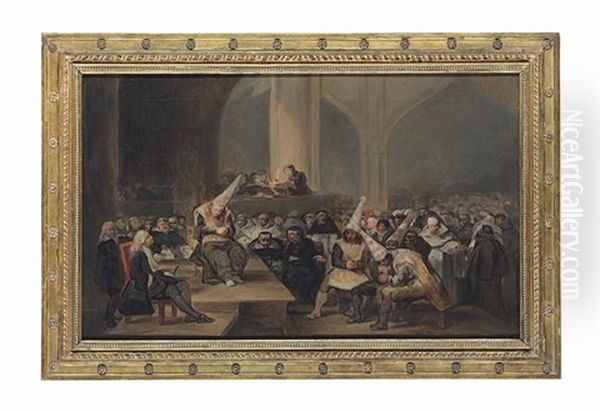

He revisited many of Goya's signature subjects: the vibrant chaos of bullfights, the eerie rituals of witchcraft and sabbaths, the solemnity and sometimes critique embedded in religious processions and pilgrimages, the shadowy proceedings of the Inquisition, and the depiction of majos and majas (stylishly dressed common folk). Lucas Velázquez approached these themes with a similar energy and expressive brushwork, often capturing the turbulent atmosphere that Goya mastered.

However, Lucas Velázquez was not simply replicating Goya's work. He often brought his own Romantic sensibility to these subjects. A notable example is his painting Procesión interrumpida por la tormenta (Procession Interrupted by the Storm). While clearly inspired by Goya's depictions of religious events, Lucas Velázquez infuses the scene with a softer touch, warmer tones, and a greater sense of human vulnerability and sympathy, slightly tempering the biting satire often found in Goya's interpretations. He translated Goya's vision into the language of mid-19th-century Romanticism.

This profound connection inevitably led to confusion. Lucas Velázquez's skill in emulating Goya's style was such that many of his works were, and sometimes still are, misattributed to Goya himself. This has complicated the study of both artists and occasionally caused controversy in the art market and academic circles. Distinguishing Lucas Velázquez's hand often requires careful analysis of brushwork, color palette, and underlying sentiment, recognizing his unique, slightly more flamboyant Romantic interpretation compared to Goya's often starker vision.

A Career in Romantic Spain: Patronage and Recognition

Lucas Velázquez's professional career gained significant momentum around the mid-19th century. His connection with the Spanish establishment began formally in 1849 when he painted a landscape for Francis, Duke of Cádiz, the husband of Queen Isabella II. This commission marked the beginning of a period of royal favor that would elevate his status considerably within the Spanish art world.

His growing reputation led to a prestigious royal commission: the decoration of the ceiling of the Teatro Real (Royal Theatre) in Madrid. Successfully completing this project earned him the coveted title of "Pintor Honorario de Cámara" (Honorary Court Painter) from Queen Isabella II. This title, while perhaps not carrying the full weight it did in previous centuries, was a significant mark of distinction and solidified his position within the artistic elite.

Further recognition came in 1853 when he was awarded the Knighthood of the Order of Charles III, a prestigious civil honor. These accolades, combined with his undeniable talent and prolific output, placed Lucas Velázquez at the forefront of the Spanish Romantic movement during its peak years. He navigated the complex social and artistic circles of Madrid, associating with figures connected to the court, including potentially other artists favored by the monarchy, such as Federico de Madrazo, son of his former fellow student José.

This period of success, however, was tied to the fortunes of the monarchy. Lucas Velázquez enjoyed the benefits of royal patronage and the stability it provided. His work from this era often reflects the confidence and vibrancy of an artist at the height of his powers, producing numerous paintings that captured the imagination of his contemporaries and secured his place in the narrative of Spanish Romanticism.

Diverse Themes: From Bullrings to Ruins

While the Goya-esque themes formed a core part of his output, Eugenio Lucas Velázquez explored a remarkably diverse range of subjects throughout his career, showcasing his versatility and broad artistic interests. His oeuvre extends far beyond the dramatic scenes of bullfights and witchcraft for which he is often best known.

Landscapes were a consistent interest, evolving from his early works possibly influenced by Genaro Pérez Villaamil to later, more atmospheric interpretations of nature. He captured the rugged Spanish terrain, often imbuing it with a sense of Romantic drama or serene beauty. His travel sketches from later life further demonstrate his keen eye for capturing the essence of a place, whether the mountains of Switzerland or the coastlines of the Basque Country.

Architectural ruins held a particular fascination for him, a common trope within Romanticism symbolizing the passage of time and the sublime power of decay. His painting simply titled Ruins exemplifies this interest, presenting a detailed yet evocative depiction of crumbling structures. He rendered these scenes with a sense of monumentality and a literary quality, inviting contemplation on history and transience.

Social customs and historical events also featured prominently. His depictions of bullfights, such as the Cowboy Bullfight series from the 1860s or works like Bullfight, were not just spectacles of violence but reflections on Spanish identity, courage, and the confrontation with death – key Romantic preoccupations. He also tackled scenes related to the Inquisition, reflecting a continued engagement with Spain's complex history and Goya's legacy of social commentary.

Furthermore, Lucas Velázquez ventured into fantasy and even Orientalist themes, reflecting the broader 19th-century European fascination with the exotic and the imagined. This thematic breadth demonstrates an artist constantly seeking new avenues for expression, moving fluidly between observed reality, historical interpretation, and pure invention, all filtered through his distinctive Romantic lens.

Artistic Style: Energy, Technique, and Evolution

Eugenio Lucas Velázquez's style is characterized by its energy, expressive brushwork, and dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro). Rooted in his study of Goya and Diego Velázquez, he developed a technique that was both technically proficient and highly personal, perfectly suited to the tenets of Romanticism. His paintings often feel alive with movement and emotion.

His brushwork is typically fluid and visible, sometimes applied with a boldness that anticipates later movements. He wasn't afraid to leave strokes apparent, contributing to the dynamism of his compositions. This is evident in works like Coach in a Storm, where the swirling paint effectively conveys the violence of the weather and the precariousness of the situation. His handling of paint creates texture and enhances the emotional impact of the scene.

Color played a crucial role in his work. He employed strong contrasts and often favored rich, dramatic palettes to heighten the mood, whether depicting the vibrant costumes of a festival or the somber tones of a nocturnal scene. His use of light is equally masterful, carving figures out of darkness and creating focal points that draw the viewer's eye into the narrative.

A particularly innovative aspect of his technique was his use of "manchas" – spots or stains of ink or watercolor wash. This method, possibly inspired by the "blot" techniques promoted by the English artist Alexander Cozens, involved applying washes in a seemingly random manner to suggest forms and atmosphere, particularly in his drawings and sketches. These works possess a remarkable freedom and abstraction, demonstrating a willingness to experiment that was quite advanced for his time. The French writer Victor Hugo, himself an accomplished user of wash techniques, admired this aspect of Lucas Velázquez's work.

His style evolved throughout his career. While the Goya influence remained strong, his later works, especially the sketches, show an increasing freedom and abstraction. The rapid, expressive application of paint and ink in these pieces creates a sense of immediacy and raw energy, moving beyond detailed representation towards capturing fleeting moments and emotional states. This evolution showcases his journey from a follower of past masters to an innovative artist in his own right.

Later Life, Travels, and Final Years

The political upheavals in Spain during the latter part of Eugenio Lucas Velázquez's life directly impacted his career. The Glorious Revolution of 1868 led to the exile of his patron, Queen Isabella II. With the loss of royal protection and commissions, Lucas Velázquez faced increasing financial difficulties. The stability and prestige he had enjoyed during the mid-century began to wane.

Despite these challenges, his artistic drive remained undiminished. Between 1868 and 1869, he embarked on extensive travels through Europe. He visited Italy, the cradle of Renaissance and Baroque art, and Switzerland, whose dramatic Alpine landscapes appealed to the Romantic sensibility. He also spent time in the Basque Country in northern Spain. These journeys were artistically productive, resulting in a series of travel sketches.

These later sketches, often executed using his characteristic "manchas" technique, are notable for their freshness and spontaneity. They capture his impressions of different landscapes and environments with remarkable freedom. These works demonstrate his continued exploration of expressive techniques and his enduring connection to the visual world, even as his personal circumstances became more precarious. His travels may also have brought him into contact with broader European artistic currents, potentially reinforcing influences like that of the French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix, whose work he might have encountered earlier in Paris.

Eugenio Lucas Velázquez returned to Madrid but did not regain his former prosperity. He passed away in 1870 at the relatively young age of 52, his final years marked by a decline in fortune but not in artistic spirit. He left behind a substantial body of work reflecting the passions, conflicts, and artistic currents of his time.

Legacy and Art Historical Standing

Eugenio Lucas Velázquez occupies a significant, albeit complex, position in Spanish art history. While perhaps overshadowed during his lifetime and immediately after by the colossal figure of Goya, his reputation has grown considerably through modern scholarship and appreciation. He is now firmly recognized as a major exponent of Spanish Romanticism.

His primary legacy lies in his unique relationship with Goya. He was more than an imitator; he was an interpreter who kept Goya's spirit alive and relevant for a new generation. He successfully translated Goya's powerful, often unsettling vision into the more overtly dramatic and sometimes picturesque language of 19th-century Romanticism. This dialogue between the two artists enriches our understanding of both.

His technical skill and stylistic innovations also contribute to his importance. His energetic brushwork, dramatic compositions, and particularly his experimental "manchas" technique demonstrate a forward-looking aspect to his art, hinting at the looser handling of paint that would characterize later movements like Impressionism.

His influence extended directly to his son, Eugenio Lucas Villamil (also known as Eugenio Lucas Velázquez Padilla, 1858-1918). The younger Lucas continued his father's style, also producing works inspired by Goya, ensuring a continuation of this artistic lineage into the early 20th century. However, distinguishing the works of father and son can sometimes present attribution challenges, adding another layer to the study of the Lucas 'dynasty'.

Today, Lucas Velázquez's works are held in major collections worldwide, including the Prado Museum, the Lázaro Galdiano Museum in Madrid, and the Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, which houses the significant The Dawn Procession. He is studied alongside other Spanish artists of the era who navigated the transition from Goya's influence, such as the costumbrista painter Leonardo Alenza y Nieto, and the more academic Romantics like Federico de Madrazo.

The persistent issue of attribution, stemming from his stylistic proximity to Goya, remains a key aspect of his legacy. While complicating matters, it also underscores his exceptional ability to capture the essence of his great predecessor. He remains a vital figure for understanding the evolution of Spanish art after Goya and the specific character of Spanish Romanticism.

Conclusion: A Distinctive Voice in Spanish Romanticism

Eugenio Lucas Velázquez was an artist defined by his deep connection to Francisco Goya, yet he forged a distinctive path within the landscape of 19th-century Spanish art. His work embodies the spirit of Romanticism – its drama, its emotional intensity, its fascination with history, folklore, and the power of nature. From his early studies in the Prado, copying the masters Diego Velázquez and especially Goya, to his mature works enjoying royal patronage, and through his later travels and experiments with technique, he remained a dynamic and expressive painter.

He explored a wide array of themes, mastering the Goya-esque subjects of bullfights and witchcraft while also excelling in landscape and the depiction of architectural ruins. His technical innovations, particularly the "manchas" technique, reveal an artist pushing the boundaries of representation. Though sometimes confused with Goya or his own son, Eugenio Lucas Villamil, and perhaps not achieving the universal fame of his primary influence, Lucas Velázquez's contribution is undeniable. He stands as a crucial link in the chain of Spanish art, a master of Romantic expression whose vibrant, often turbulent canvases continue to engage viewers today. His legacy is that of a passionate interpreter and a powerful artist in his own right.