Louis de Moni, a notable figure in 18th-century Dutch painting, carved a distinct niche for himself by emulating and reinterpreting the celebrated genre scenes of the Dutch Golden Age. Active during a period when the towering achievements of 17th-century artists cast a long shadow, de Moni's work reflects both a reverence for the past and a subtle adaptation to contemporary tastes. His paintings, often characterized by their meticulous detail and quiet domesticity, found favor with collectors and continue to be subjects of art historical interest.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

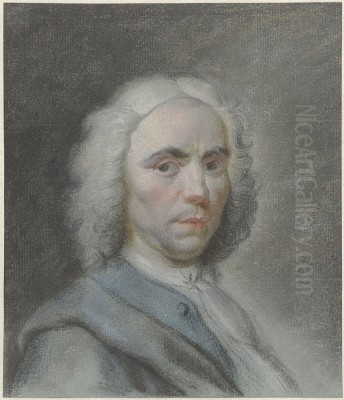

Born in Breda in 1698, Louis de Moni's artistic journey began under the tutelage of several masters who would shape his developing style. His initial instruction came from F. van Kessel, likely a descendant or relative of the famed Van Kessel dynasty of painters known for their detailed still lifes and animal paintings, such as Jan van Kessel the Elder. He also studied with K. E. Biset, an artist about whom less is widely documented, but whose influence would have contributed to de Moni's foundational skills.

A pivotal moment in de Moni's training was his apprenticeship with Philip van Dijk. Van Dijk, active primarily in The Hague and Middelburg, was a respected painter of portraits and elegant genre scenes, himself influenced by the refined techniques of artists like Caspar Netscher and Godfried Schalcken. Studying under Van Dijk, who was known for his polished finish and ability to capture the textures of rich fabrics, undoubtedly honed de Moni's eye for detail and composition. This period in The Hague exposed de Moni to a sophisticated artistic environment, further steeping him in the traditions of Dutch fine painting.

Artistic Style: Emulation and Individuality

Louis de Moni is perhaps best known for his adeptness at working in the style of the Leiden Fijnschilders, or "fine painters," of the 17th century. This school, spearheaded by Gerrit Dou, a pupil of Rembrandt, emphasized meticulous detail, smooth brushwork, and often, small-scale compositions depicting intimate interior scenes. De Moni frequently created works that were direct copies or close imitations of masters such as Dou, Frans van Mieris the Elder, Gabriel Metsu, and Pieter Cornelisz van Slingelandt. His ability to replicate their polished surfaces and intricate rendering of textures was remarkable.

However, de Moni was not merely a copyist. While his imitative works catered to a market that still highly valued Golden Age aesthetics, his original compositions reveal a distinct artistic personality. These pieces often feature a somewhat cooler color palette compared to the warmer tones of many 17th-century masters. His style in these original works could be described as simpler, with a characteristic use of neutral and greyish tones. His brushwork, particularly in rendering fabrics, faces, and figures, could be broader and more fluid than the almost invisible brushstrokes of the strictest Fijnschilders. This suggests a subtle modernization or personal interpretation of the established tradition.

Thematic Focus and Subject Matter

De Moni's oeuvre primarily consists of genre scenes, capturing everyday life with a quiet charm. Kitchen interiors and domestic settings were recurrent themes, populated by figures engaged in simple activities. These scenes often evoke a sense of tranquility and order, hallmarks of the Dutch genre tradition. He depicted maids at work, families interacting, and individuals in moments of contemplation or leisure.

His subjects also included specific popular pastimes. For instance, scenes of figures playing games, such as the "Ganzenbord" (Game of the Goose), appear in his work, reflecting a broader interest in social interactions and leisure activities common in Dutch art since the time of Jan Steen or Adriaen van Ostade. Candlelight scenes, a specialty of artists like Godfried Schalcken, also feature in de Moni's repertoire, allowing him to explore chiaroscuro effects and create an intimate, focused atmosphere. His depictions of market vendors, such as fishmongers, connect to a long tradition of portraying everyday commerce, seen in the works of artists like Pieter Aertsen and Joachim Beuckelaer in the 16th century, and continued by many 17th-century painters.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

Several works by Louis de Moni are frequently cited and help illustrate his artistic approach. While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné is essential for a full overview, certain pieces highlight his skills and thematic preferences.

"A Maid in a Kitchen with a Youth and a Girl Playing 'Ganzenbord'" is a prime example of his domestic genre scenes. Such a painting would typically showcase his ability to render different textures – from earthenware pots to simple garments – and to create a narrative within a confined space. The interaction between the figures, engaged in a popular board game, adds a lively element to the composition.

"Woman by Candlelight Feeding Two Children" demonstrates his engagement with nocturnal scenes. The concentrated light source would allow for dramatic contrasts between light and shadow, focusing attention on the tender interaction. This theme echoes the intimate family scenes popularized by artists like Quiringh van Brekelenkam or Nicolaes Maes, albeit with the specific lighting challenges embraced by Schalcken.

His "Fishmonger" and "The Drinker" represent another facet of genre painting, depicting figures from everyday life, sometimes with a moralizing undertone or simply as character studies. "The Drinker," for example, might recall the tavern scenes of Adriaen Brouwer or David Teniers the Younger, though likely rendered with de Moni's more restrained and polished manner.

A piece titled "Woman in a White Satin Dress" suggests an engagement with the portrayal of luxurious fabrics, a skill highly prized among the Fijnschilders. The rendering of satin, with its reflective sheen, was a benchmark of technical prowess for artists like Gerard ter Borch and the aforementioned Frans van Mieris the Elder. De Moni's version would aim to capture this elegance.

"A Laughing Boy in a Window" is a motif made famous by Gerrit Dou and his followers, often featuring a figure leaning out of a stone window niche, sometimes surrounded by symbolic objects. De Moni's interpretation would likely follow this established compositional type, showcasing his ability in portraiture and detailed rendering.

The painting "A Group of Gamblers," noted as being inspired by David II Teniers, indicates de Moni's awareness of Flemish genre traditions as well. Teniers was renowned for his lively depictions of peasant life and tavern scenes, and de Moni's work in this vein would adapt these themes, perhaps with a Dutch sensibility.

Technique, Palette, and Artistic Process

De Moni's technique varied depending on whether he was creating an original composition or an imitation. In his copies, he would strive to match the meticulousness and enamel-like finish of the Leiden Fijnschilders. This involved careful layering of glazes and precise brushwork to achieve smooth transitions and rich detail.

In his original works, while still detailed, there is often a discernible softness or a slightly broader application of paint. His preference for cooler, sometimes more subdued or greyish, tonalities distinguishes some of his paintings from the often warmer, richer palettes of the 17th-century artists he admired. This cooler palette and simpler style, as described in art historical literature, might reflect evolving 18th-century tastes or simply his personal preference.

The fact that he copied works by artists like Hans Jordaens, a painter known for historical and mythological scenes as well as genre, suggests a versatility in his imitative practice, though he is primarily remembered for his genre pieces. The act of copying was a standard part of artistic training and also a legitimate way to produce marketable works for collectors who desired the style of renowned but deceased masters.

Reception, Patronage, and Legacy

Louis de Moni achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime. His works were sought after by collectors, and records show that his paintings, particularly his skillful imitations, could command high prices at auction, sometimes even rivaling or exceeding the prices of original 17th-century pieces by lesser-known masters. This speaks to the enduring appeal of the Golden Age style and de Moni's success in capturing its essence.

His paintings found their way into significant collections in Leiden and beyond. The detailed auction catalogues from the period, such as those from sales in Leiden in 1772 (the year after his death), list numerous works by de Moni, often specifying if they were "in the manner of" or copies after specific artists like Dou or Metsu. This documentation is invaluable for understanding his output and contemporary reputation. Prominent collectors of the era, such as Jan Tak, are known to have owned works by de Moni, indicating his acceptance within discerning art circles.

Today, Louis de Moni's paintings are held in various museum collections, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the British Museum in London. His work is a subject of ongoing academic study, with scholars like Junko Aono having conducted in-depth research into his methods of imitation and innovation within the context of 18th-century Dutch art. Such research helps to illuminate the complex relationship between 18th-century artists and their Golden Age predecessors, and the dynamics of the art market of the time.

His participation in exhibitions, even posthumously, such as documented showings in St. Petersburg, further attests to the international reach and appreciation of Dutch art, including the contributions of 18th-century figures like de Moni. Literature such as Eric Zaslow's "EREMITAS AUS BERLIN" and Adriaan Waaijer's catalogue raisonné contribute to the modern understanding of his life and work.

De Moni in the Broader Context of 18th-Century Dutch Art

The 18th century in Dutch art is often characterized as a period of consolidation rather than radical innovation, particularly when compared to the explosive creativity of the 17th century. Many artists, like de Moni, looked to the Golden Age for inspiration and models of excellence. This was partly driven by market demand, as collectors continued to favor the established styles and subjects of the previous century.

Artists like Willem van Mieris (son of Frans van Mieris the Elder) and Adriaen van der Werff (though his main activity was late 17th/early 18th century) continued the Fijnschilder tradition with great technical skill. De Moni operated within this broader trend of upholding and perpetuating these meticulous painting techniques. While some contemporaries like Cornelis Troost developed a more distinctively 18th-century Rococo-influenced style in their genre scenes and theatrical portraits, de Moni remained more firmly rooted in the 17th-century aesthetic. His focus was less on the playful elegance of the Rococo and more on the detailed realism and quietude of artists like Dou and Metsu.

His work, therefore, represents an important aspect of 18th-century Dutch art: the preservation and reinterpretation of a rich artistic heritage. He was not an isolated figure but part of a larger movement that valued technical skill and the established genres of the Golden Age. His ability to so convincingly evoke the spirit of these earlier masters, while occasionally infusing his work with his own subtle stylistic nuances, secured his place in Dutch art history.

Conclusion

Louis de Moni passed away in Leiden in 1771, at the age of 73, leaving behind a body of work that testifies to his skill as a painter and his deep understanding of Dutch Golden Age art. He successfully navigated the art market of his time by catering to the prevailing taste for meticulously rendered genre scenes, often directly referencing or copying the works of celebrated 17th-century masters. Yet, within this framework, he also developed a recognizable personal style characterized by a cooler palette and a slightly more simplified approach in his original compositions.

As an artist who bridged the reverence for the past with the sensibilities of his own era, Louis de Moni remains a significant figure for understanding the continuity and evolution of Dutch painting in the 18th century. His works continue to be appreciated for their technical finesse, their charming depictions of everyday life, and the insight they offer into the artistic dialogues between two distinct centuries.