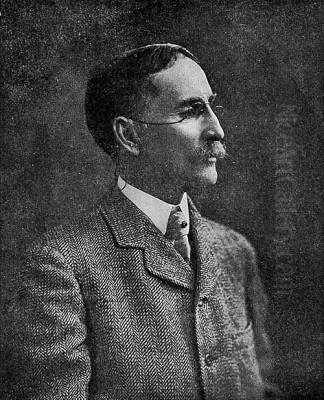

Lovell Birge Harrison stands as a significant figure in the annals of American art, a painter, teacher, and writer whose career bridged the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born on October 28, 1854, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and passing away in 1929, Harrison became one of the foremost proponents and practitioners of Tonalism, an artistic style that emphasized mood, atmosphere, and a harmonious, often subdued, palette to evoke the poetic qualities of the landscape. His work, deeply influenced by his studies both in America and abroad, captured the subtle nuances of light and weather, particularly the ethereal beauty of twilight, moonlight, and snow-laden scenes. Beyond his own artistic output, Harrison's influence extended through his influential teaching at the Art Students League's summer school in Woodstock, New York, and his seminal book, Landscape Painting, which guided a generation of aspiring artists.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Philadelphia

Lovell Birge Harrison, often known as Birge Harrison, was born into a family with artistic inclinations; his younger brother, Thomas Alexander Harrison, would also become a distinguished painter, known particularly for his marine scenes. Philadelphia in the mid-nineteenth century was a burgeoning cultural center, and it was here that Harrison received his initial artistic training. In 1874, he enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), one of the oldest and most prestigious art institutions in the United States.

At PAFA, Harrison came under the tutelage of Thomas Eakins, a towering figure in American realism. Eakins's rigorous approach, emphasizing anatomical accuracy, direct observation, and an unflinching depiction of reality, provided a strong foundation for his students. While Harrison's mature style would diverge significantly from Eakins's stark realism, the discipline and observational skills instilled during this period undoubtedly shaped his artistic development. It was also during this formative time that Harrison reportedly encountered the work and perhaps the person of John Singer Sargent, whose burgeoning international success may have further fueled Harrison's ambition to seek training in Paris, the undisputed art capital of the world. The decision to pursue art seriously was a significant one, as it meant forgoing a more conventional career path, a choice many aspiring artists of his generation faced.

Parisian Studies and the Embrace of New Influences

Like many ambitious American artists of his era, Harrison recognized the necessity of European study to refine his craft and broaden his artistic horizons. He traveled to Paris, immersing himself in its vibrant art scene. He sought instruction from some of the leading academic painters of the day, enrolling in the atelier of Alexandre Cabanel at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. Cabanel was a highly successful artist, celebrated for his historical, classical, and portrait subjects, and a staunch defender of the academic tradition. Studying under Cabanel would have exposed Harrison to the meticulous draftsmanship and polished finish prized by the French Salon.

Harrison also studied with Carolus-Duran, a charismatic and influential teacher whose approach was somewhat more progressive than Cabanel's. Carolus-Duran, himself a renowned portraitist, encouraged a bolder handling of paint and a greater emphasis on capturing the overall effect rather than getting lost in minute details. His atelier attracted numerous American students, including John Singer Sargent, who became one of his most famous pupils. The contrasting methodologies of Cabanel and Carolus-Duran provided Harrison with a diverse academic grounding.

Beyond the formal academies, Harrison was profoundly affected by the prevailing artistic currents in France. He was particularly drawn to the Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Charles-François Daubigny, Théodore Rousseau, and Jean-François Millet. These artists had moved away from idealized landscapes, preferring to paint directly from nature, capturing its moods and transient effects with a subdued palette and an emphasis on atmosphere. Their work resonated with a romantic sensibility and a deep appreciation for the rural landscape, qualities that would become hallmarks of Harrison's own Tonalist aesthetic.

Another crucial influence during his time in Europe, and indeed throughout his career, was the work of the expatriate American artist James McNeill Whistler. Whistler, based in London and Paris, was a leading figure in the Aesthetic Movement and a pioneer of what would become known as Tonalism. His "Nocturnes" and other atmospheric landscapes, with their subtle gradations of color, simplified forms, and emphasis on "art for art's sake," made a lasting impression on Harrison. Whistler's ability to evoke a powerful mood through a limited range of tones and a focus on the abstract qualities of color and composition was a revelation for many younger artists.

The Development of a Tonalist Vision

Upon his return to the United States, Harrison began to synthesize these diverse influences into a distinctive personal style. He became a leading voice in the Tonalist movement, which flourished in America from roughly the 1880s through the 1910s. Tonalism was less a formal school and more a shared sensibility, characterized by soft, diffused light, muted colors (often greens, blues, grays, and browns), and an overall emphasis on creating a harmonious and evocative mood. Tonalist painters sought to capture the spiritual or poetic essence of the landscape rather than a literal transcription of it. Their works often depicted twilight, dawn, mist, or moonlight, times when details are obscured, and the world appears veiled and mysterious.

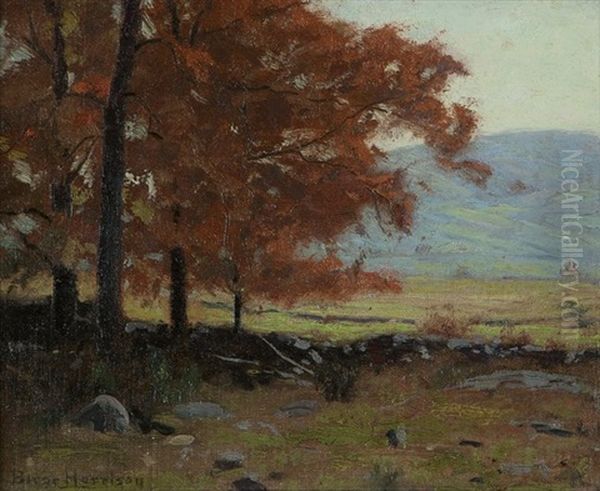

Harrison excelled in capturing these liminal moments. He was particularly renowned for his snow scenes, where he masterfully rendered the subtle play of light on snow, the delicate blues and violets of shadows, and the quiet hush that blankets a winter landscape. His paintings were not merely topographical records but deeply felt responses to nature, imbued with a sense of tranquility and introspection. He often worked with a limited palette, skillfully manipulating values and hues to create a unified and atmospheric effect. This approach stood in contrast to the brighter colors and broken brushwork of Impressionism, which was also gaining currency at the time. While Impressionists were primarily concerned with the optical effects of light, Tonalists like Harrison were more interested in its emotional and spiritual resonance.

His urban scenes, particularly those of New York City, also demonstrated his Tonalist sensibility. He depicted city streets veiled in snow or mist, or illuminated by the soft glow of gaslight at dusk, transforming the mundane into something poetic and beautiful. George Inness, another prominent American landscape painter whose later work shared affinities with Tonalism, reportedly encouraged Harrison to focus on the atmospheric effects of sunrise and sunset, further reinforcing his inclination towards these evocative times of day.

Signature Works and Artistic Themes

Lovell Birge Harrison's oeuvre includes numerous paintings that exemplify his Tonalist approach and his mastery of atmospheric effects. Among his most celebrated works is Fifth Avenue at Twilight, painted around 1910. This iconic piece captures the bustling New York City thoroughfare as evening descends, with the warm glow of streetlights and shop windows reflecting on the snow-covered street, and the silhouettes of horse-drawn carriages and early automobiles moving through the hazy atmosphere. The painting is a symphony of muted blues, grays, and soft yellows, perfectly conveying the mood of a winter evening in the city.

Another significant work, The Sawmill at Shady (circa 1905), depicts a more rural scene, likely near the Woodstock art colony where Harrison would later become so influential. The painting showcases his ability to find beauty in humble subjects, rendering the sawmill and its surroundings with a quiet dignity and a focus on the interplay of light and shadow in a winter landscape. The subtle color harmonies and the overall sense of stillness are characteristic of his best Tonalist work.

Many of Harrison's paintings bear titles that directly indicate his preoccupation with specific times of day or seasons, such as Autumn Lake, Autumn Forest, Autumn Countryside, and Autumn Valley. These works, like his winter scenes, would have emphasized the particular atmospheric qualities and color palettes associated with autumn – the soft, hazy light, the muted golds and russets, and the melancholic beauty of the changing season. He was adept at conveying the feeling of a place, the intangible qualities that transcend mere visual representation. His landscapes often invite contemplation, drawing the viewer into a world of quiet beauty and subtle emotion. The human presence in his landscapes, when included, is often small and integrated into the overall scene, emphasizing the dominance and enveloping power of nature.

The Educator: Woodstock and "Landscape Painting"

Beyond his achievements as a painter, Lovell Birge Harrison made an enduring contribution to American art as an educator. He was instrumental in the development of the Art Students League's summer school of landscape painting in Woodstock, New York. In 1906, Harrison was invited to become the director and chief instructor of this school, a position he held with distinction until 1910. Woodstock, nestled in the Catskill Mountains, provided an ideal setting for landscape painting, and under Harrison's guidance, it quickly became one of the most important art colonies in America.

Harrison was a charismatic and inspiring teacher. His pedagogical approach, like his art, emphasized the importance of capturing the mood and spirit of nature. He encouraged his students to observe carefully, to simplify, and to seek out the underlying harmony in a scene. He taught them the principles of Tonalism, including the use of a limited palette and the importance of value relationships in creating atmospheric depth. Many artists who would go on to have successful careers studied with Harrison at Woodstock, including John F. Carlson, who himself became a noted landscape painter and influential teacher, carrying on and adapting Harrison's Tonalist principles. Other artists associated with the Woodstock colony, either as students or colleagues, included George Bellows, Eugene Speicher, and Leon Kroll, though their styles often evolved in different directions.

In 1909, Harrison codified his teaching philosophy in the book Landscape Painting. This volume, based on his lectures at Woodstock, became a standard instructional text for a generation of American landscape painters. In it, he discussed topics such as composition, color, values, and the importance of "truth in art," which for Harrison meant not a slavish imitation of reality but a truthful rendering of the artist's emotional response to nature. He advocated for painting outdoors (en plein air) to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere directly, but also stressed the importance of memory and studio work to refine and imbue the painting with deeper feeling. The book was praised for its clarity, practicality, and its insightful articulation of Tonalist aesthetics.

The Woodstock Art Colony and a Community of Artists

The establishment and success of the Art Students League's summer school under Lovell Birge Harrison's leadership were pivotal in transforming Woodstock into a thriving year-round art colony. Harrison's presence attracted other artists, writers, and musicians, creating a vibrant intellectual and creative community. The Byrdcliffe Arts and Crafts Colony, founded nearby in 1902 by Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead, Hervey White, and Bolton Brown, had already laid some groundwork for an artistic community, but Harrison's school significantly amplified Woodstock's reputation as a center for landscape painting.

The atmosphere at Woodstock was one of camaraderie and shared purpose. Artists gathered to paint the scenic Catskill landscapes, to discuss art, and to learn from one another. Harrison fostered an environment that was both rigorous and supportive. He encouraged individuality while also instilling the core principles of Tonalist landscape painting. The legacy of this period is still felt in Woodstock, which remains an active arts community. Harrison's role in shaping this environment was crucial, and he is remembered as one of the founding fathers of the Woodstock art colony. His influence extended beyond his direct students, helping to popularize a certain approach to landscape painting that valued mood and personal expression.

Interactions with Contemporaries and Artistic Circles

Throughout his career, Lovell Birge Harrison moved within significant artistic circles. His brother, Alexander Harrison, achieved international fame for his marine paintings and figure studies, often exhibiting at the Paris Salon. While their styles differed—Alexander's work often featured brighter light and more dynamic compositions—they shared a commitment to artistic excellence and would have undoubtedly exchanged ideas and influences.

Harrison's early encounter with Thomas Eakins at PAFA provided a solid, if contrasting, foundation to his later Tonalist leanings. In Paris, his studies with Cabanel and Carolus-Duran placed him at the heart of academic training, while his admiration for the Barbizon painters and Whistler connected him to more progressive, atmospheric approaches.

In America, Harrison was part of a cohort of artists exploring Tonalism. Figures like Dwight William Tryon, J. Francis Murphy, and Henry Ward Ranger were also prominent Tonalist painters. Tryon was known for his delicate, poetic landscapes, often depicting dawn or dusk. Murphy specialized in subtle, atmospheric scenes, frequently of autumn or early winter. Ranger, sometimes called the "dean" of the Old Lyme Art Colony in Connecticut (another important center for American Impressionism and Tonalism), also worked in a Tonalist vein, though his style could be more robust. While each artist had a unique voice, they shared a common interest in capturing the subjective experience of nature through harmonious color and diffused light. Harrison's work and writings helped to define and popularize this aesthetic. He exhibited widely in the United States, including at the National Academy of Design, where he was elected an Associate in 1902 and a full Academician in 1910, and at the Society of American Artists.

Critical Reception and Shifting Artistic Tides

During the peak of Tonalism's popularity, from the 1890s through the early 1910s, Lovell Birge Harrison enjoyed considerable acclaim. His paintings were admired for their poetic beauty, their technical skill, and their sensitive rendering of atmosphere. His snow scenes, in particular, were highly sought after. His book, Landscape Painting, was well-received and widely adopted. He won numerous awards and medals at major exhibitions, cementing his reputation as one of America's leading landscape painters.

However, the art world is ever-evolving. By the 1910s and 1920s, new artistic movements were gaining prominence in America. Impressionism, with its brighter palette and focus on capturing the fleeting effects of light with broken color, had already established a strong presence, with artists like Childe Hassam and Willard Metcalf leading the way. Subsequently, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, and other European modernist styles began to make their impact, particularly after the groundbreaking Armory Show of 1913 in New York City. These newer movements often emphasized bold color, formal experimentation, and a more radical departure from traditional representation.

In this changing artistic climate, Tonalism, with its quiet introspection and subtle palette, began to be perceived by some critics and younger artists as old-fashioned or overly sentimental. Harrison's focus on "moonlight and nostalgia," as some characterized it, seemed less relevant to a modernizing America. While his work continued to be respected, the avant-garde had moved in different directions. This shift in taste was a common experience for many artists of Harrison's generation whose careers were rooted in late nineteenth-century aesthetics.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, Lovell Birge Harrison's health began to decline, which may have curtailed his painting activity. His wife, the artist Eleanor Henderson Harrison, passed away in 1928, a year before his own death in 1929. He spent more time traveling and writing during this period. Despite the changing artistic fashions, Harrison's contributions remained significant.

His legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he created a body of work that beautifully encapsulates the Tonalist aesthetic, leaving behind evocative images of the American landscape that continue to resonate with viewers. His paintings are held in the collections of major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

As an educator, his impact was profound. Through his teaching at Woodstock and his influential book, Landscape Painting, he shaped the development of countless artists. He helped to establish landscape painting as a serious and respected genre in American art and provided a clear methodology for capturing its poetic essence. The Woodstock art colony, which he helped to nurture, remains a testament to his vision and dedication.

While Tonalism was eclipsed for a time by modernism, there has been a renewed appreciation for its quiet beauty and emotional depth in more recent decades. Art historians and collectors now recognize Lovell Birge Harrison as a key figure in this uniquely American art movement, an artist who masterfully conveyed the subtle moods and enduring allure of the natural world. His ability to translate the intangible qualities of atmosphere and light into paint, and to imbue his scenes with a profound sense of poetry, secures his place as an important and beloved American artist. His influence can be seen not only in the work of his direct students like John F. Carlson but also in the broader tradition of American landscape painting that values personal expression and a deep connection to place.

Conclusion: A Poet of the American Landscape

Lovell Birge Harrison's life and work offer a compelling chapter in the story of American art. From his early studies in Philadelphia and Paris to his mature career as a leading Tonalist painter and influential teacher, he consistently sought to capture the poetic essence of the landscape. His evocative depictions of snow-covered fields, twilit city streets, and misty mornings are more than mere representations; they are invitations to experience the subtle beauty and quiet moods of nature. Through his paintings, his writings, and his dedicated teaching, Harrison left an indelible mark on American art, championing an aesthetic that valued harmony, atmosphere, and the deeply personal response of the artist to the world around them. He remains a luminary of American Tonalism, a true poet of the American landscape.