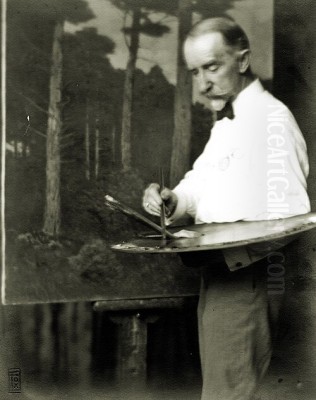

Charles Warren Eaton stands as a significant figure in the landscape of American art history, particularly celebrated for his contributions to the Tonalist movement during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born on February 22, 1857, in Albany, New York, Eaton's life journey took him from humble beginnings to becoming one of the most respected landscape painters of his era. His evocative depictions of nature, characterized by their moody atmospheres, subtle palettes, and profound sense of tranquility, earned him critical acclaim and a lasting legacy. Eaton passed away in 1937, leaving behind a body of work that continues to resonate with viewers for its poetic beauty and quiet introspection. He is perhaps most famously known as "The Pine Tree Painter" for his distinctive and numerous portrayals of pine trees, often silhouetted against twilight or moonlit skies.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Charles Warren Eaton's origins were modest. Born into a family of limited financial means in Albany, the capital of New York State, his childhood necessitated work from a young age. He began contributing to the family income at the tender age of nine. Formal schooling was likely brief, overshadowed by the practical demands of earning a living. This early exposure to labor, however, did not extinguish a nascent artistic sensibility. A pivotal moment occurred when Eaton encountered an amateur art exhibition organized by a friend's family. Seeing paintings, even amateur ones, sparked something within him, igniting an interest in visual art that would shape the course of his life.

This newfound passion prompted a significant life change. In 1879, at the age of 22, Eaton made the decisive move from Albany to the bustling metropolis of New York City. The city offered far greater opportunities for artistic exposure and education, though his financial situation remained constrained. He initially supported himself through various forms of employment during the day. His evenings, however, were dedicated to pursuing his artistic ambitions. This period marked the formal beginning of his art education, laying the groundwork for his future career.

Forging an Artistic Path in New York

New York City provided Eaton with access to esteemed institutions where he could hone his craft. He enrolled in evening classes at both the prestigious National Academy of Design and the progressive Art Students League. These institutions offered rigorous training in drawing and painting, exposing him to different artistic philosophies and techniques. Studying alongside other aspiring artists and under the guidance of established figures provided invaluable experience. Balancing demanding day jobs with intensive evening studies required immense dedication and discipline, highlighting Eaton's early commitment to his artistic calling.

By the early 1880s, Eaton felt confident enough in his skills and artistic vision to transition into painting full-time. This was a bold step, signifying his commitment to pursuing art not just as a passion but as a profession. His work soon began to gain recognition. He started exhibiting his paintings at the National Academy of Design, a crucial venue for artists seeking visibility and validation. An early milestone occurred in 1882 when the renowned writer and aesthete Oscar Wilde, during his lecture tour of America, purchased one of Eaton's paintings. This endorsement from such a prominent cultural figure provided significant encouragement and a measure of early fame. Further validation came in 1884 when his work received a positive review in The New York Times, signaling his arrival as a noteworthy artist on the New York scene. In 1886, buoyed by growing success, he felt secure enough to resign from his last regular day job, dedicating himself entirely to his art.

The Influence of Barbizon and Inness

Eaton's artistic development did not occur in isolation. He was deeply influenced by prevailing artistic currents, particularly the French Barbizon School. Painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, and Charles-François Daubigny championed a move away from idealized, historical landscapes towards more intimate, realistic depictions of the countryside, often emphasizing mood and atmosphere over precise detail. Their focus on capturing the fleeting effects of light and weather resonated strongly with Eaton and many American artists of his generation.

Within the American context, the most significant influence on Eaton was undoubtedly George Inness. A leading figure in American landscape painting, Inness himself had absorbed the lessons of the Barbizon School and evolved a deeply personal, spiritual, and atmospheric style that moved beyond mere representation. Eaton developed a close friendship with the older master, sharing a studio building with him for a time. While Eaton deeply admired Inness's work and absorbed much from his approach, particularly the emphasis on poetic mood and subjective interpretation, he maintained his own artistic identity. He was an admirer, not an imitator, forging a path that reflected his unique sensibility while acknowledging his debt to Inness's pioneering vision. Other American landscape painters like Alexander Helwig Wyant and Ralph Albert Blakelock also explored similar Tonalist directions, contributing to the artistic milieu in which Eaton thrived.

The Essence of Tonalism

Charles Warren Eaton became a key proponent of Tonalism, an American art movement that flourished roughly between 1880 and 1915. Tonalism emerged as a reaction against the detailed realism of the Hudson River School and the brighter palette of Impressionism. Its core tenets revolved around mood, atmosphere, and suggestion rather than explicit narration or topographical accuracy. Tonalist painters favored intimate, often simplified compositions, rendered in a limited range of colors – typically muted greens, browns, grays, and blues – harmoniously blended to create a unified 'tone'.

Eaton's work perfectly embodies the Tonalist aesthetic. His landscapes are rarely grand or panoramic; instead, they focus on quiet corners of nature, often depicted during the transitional moments of dawn, dusk, or under moonlight. He sought to capture the subjective feeling or emotional resonance of a place, imbuing his scenes with a sense of mystery, melancholy, or serene contemplation. Unlike the Hudson River School painters such as Thomas Cole or Asher B. Durand, who often celebrated the sublime grandeur of the American wilderness, Eaton focused on the subtle, the intimate, and the evocative. His paintings invite quiet reflection, emphasizing the spiritual or poetic aspects of the natural world. Light is paramount in his work, but it is often diffused, hazy, or ethereal, contributing to the overall dreamlike quality.

Eaton's Tonalist Vision

Eaton's specific interpretation of Tonalism was characterized by a profound sense of stillness and introspection. His landscapes are typically devoid of human figures or animals, enhancing the feeling of solitude and quietude. This absence allows the viewer to engage directly with the natural elements – the trees, the water, the sky – and the mood they convey. He was particularly drawn to the subtle interplay of light and shadow, using it to sculpt forms and create depth while maintaining an overall softness and atmospheric unity.

His preferred subjects often included meadows, woodlands, and waterways, rendered with a focus on simplified forms and harmonious color relationships. He masterfully manipulated values – the relative lightness or darkness of colors – to create gentle transitions and a cohesive visual field. The resulting works often possess a lyrical, almost musical quality, reflecting a deeply personal and emotional response to the landscape. Eaton's Tonalism was less about documenting a specific location and more about capturing a universal feeling, a sense of nostalgia, or a moment of quiet communion with nature. This approach aligned him with fellow Tonalists like Dwight William Tryon and J. Francis Murphy, who also explored the poetic potential of the American landscape through subtle tonal harmonies.

The "Pine Tree Painter"

While Eaton painted a variety of landscape subjects, he became most inextricably linked with his depictions of pine trees, specifically the Eastern White Pine. This association became so strong that he earned the moniker "The Pine Tree Painter." He found particular inspiration in the landscapes of western Massachusetts and Connecticut, especially around the area of Thompson, Connecticut, where white pines grew in abundance. These trees, with their tall, distinctive silhouettes and feathery needles, became a recurring motif, almost a signature element, in his work.

Eaton typically depicted these pines standing sentinel-like against evocative skies, often bathed in the soft, colored light of sunset or the cool, silvery glow of moonlight. His compositions frequently emphasized the verticality of the trees, contrasting their dark forms against luminous backgrounds. Works like The Pine Forest or numerous paintings titled Moonlight, Twilight, or simply Pines showcase this fascination. There is often a sense of quiet drama in these scenes, a blend of melancholy and majesty. The pines in Eaton's paintings seem to possess a symbolic weight, suggesting endurance, solitude, and a connection to something timeless and profound. This focus on a specific natural element, rendered with such consistent emotional depth, solidified his reputation and created a recognizable artistic identity.

European Travels and Broadening Horizons

Like many American artists of his generation, Eaton sought inspiration and exposure beyond national borders. He made his first significant trip to Europe in 1886, a journey that likely included time in France and the Netherlands. This trip allowed him to see firsthand the works of European masters, both old and contemporary, and potentially connect with other artists working in similar veins. He absorbed the atmospheric qualities of Dutch landscape painting and the continued influence of the Barbizon aesthetic in France.

Subsequent travels took him further afield. He developed a particular fondness for Bruges, the historic canal city in Belgium. Its medieval architecture, tranquil waterways, and often misty atmosphere provided subjects perfectly suited to his Tonalist sensibility. He painted numerous views of Bruges, capturing its quiet charm and melancholic beauty. Another favored destination was Lake Como in Italy. The dramatic scenery, where mountains meet water, offered a different kind of landscape challenge, which Eaton interpreted through his characteristic lens of mood and softened light. These European subjects, while distinct from his American pines, were rendered with the same focus on atmosphere, simplified forms, and evocative color harmonies, demonstrating the consistency of his artistic vision across diverse geographical settings. His engagement with European scenes placed him in dialogue with international trends, while his unique style remained distinctly his own.

Mastery Across Diverse Media

While primarily known for his oil paintings, Charles Warren Eaton was a versatile artist proficient in several mediums. He was particularly adept with watercolor, a medium whose fluidity and transparency lent itself well to capturing subtle atmospheric effects. His skill in this area was recognized by his peers; he was an early and active member of the American Watercolor Society, a prestigious organization dedicated to the medium, and was elected an honorary member in 1901. His watercolors often possess a luminous quality, exploring the interplay of light and water with delicate washes and controlled tones.

Eaton also worked extensively in pastel. This medium, with its soft, powdery texture and potential for rich color blending, was ideally suited to the Tonalist aesthetic. Pastels allowed him to achieve velvety surfaces and subtle gradations of tone, enhancing the dreamy, evocative quality of his landscapes. Furthermore, Eaton experimented with printmaking, particularly monotypes. This technique, which involves creating a unique print from a painted plate, allowed for spontaneous expression and painterly effects within a print medium, appealing to his interest in texture and tone. His engagement with these various media demonstrates a restless artistic curiosity and a desire to explore different means of capturing the elusive qualities of light and atmosphere that were central to his vision. There is also evidence of his interest in the aesthetic possibilities of early photography, likely informing his compositional choices and study of light.

Mature Style and Later Commissions

As the 20th century dawned, subtle shifts began to appear in Eaton's work. While remaining fundamentally rooted in Tonalism, his palette gradually brightened, and his handling of paint sometimes became bolder, perhaps reflecting the growing influence of Impressionism, championed in America by artists like Childe Hassam. However, he never fully embraced the broken brushwork or scientific color theory of Impressionism. The core of his art remained the evocation of mood and the subjective experience of nature, even when rendered with somewhat higher-keyed colors. His commitment to landscape as a vehicle for emotional expression remained constant.

A significant project in his later career came in 1921 when he was commissioned by the Great Northern Railway. The railway companies often hired prominent artists to create paintings of the scenic landscapes along their routes, using the artworks for publicity and to encourage tourism. Eaton traveled to Glacier National Park in Montana, a region of dramatic mountain scenery, pristine lakes, and, indeed, glaciers. He produced a series of paintings capturing the majestic beauty of the park. These works, while depicting grander vistas than his typical intimate scenes, still bear his hallmark sensitivity to light and atmosphere. They represent an interesting application of his style to the monumental landscapes of the American West and also reflect a growing national interest in preserving such wilderness areas. Artists like Thomas Moran had earlier played a key role in promoting National Parks through their art.

A Circle of Artists and Contemporaries

Charles Warren Eaton was part of a vibrant artistic community. His closest artistic relationship was arguably with George Inness, whose influence was profound. He also maintained friendships and professional associations with numerous other painters, particularly those associated with Tonalism and landscape painting. Among his notable contemporaries were Leonard Ochtman, a fellow Tonalist known for his poetic landscapes, who was also a friend and neighbor for a time in the Cos Cob art colony area of Connecticut. Ben Foster was another landscape painter working in a similar Tonalist vein.

Henry Ward Ranger, often considered a leader of the Tonalist movement and central to the Old Lyme art colony, was another important figure in Eaton's milieu. Eaton also associated with artists like Robert Swain Gifford and Arthur Hoeber, the latter being both a painter and an influential art critic. The broader context of Tonalism included figures like Dwight William Tryon, J. Francis Murphy, and the highly individualistic Ralph Albert Blakelock, whose moody, often dark landscapes shared some affinities with Eaton's work. The overarching influence of James McNeill Whistler, whose aesthetic theories and famous "Nocturnes" were pivotal to Tonalism's development internationally, also formed part of the backdrop against which Eaton worked. Even figure painters like Thomas Wilmer Dewing shared the Tonalist emphasis on mood and refined aesthetics. Eaton navigated this rich artistic landscape, contributing his unique voice while engaging with the ideas and works of his peers.

Accolades and Professional Recognition

Throughout his mature career, Charles Warren Eaton received significant recognition for his artistic achievements in the form of awards and prestigious memberships. His success at major national and international exhibitions underscored his standing in the art world. In 1900, his work was recognized at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, where he received an honorable mention (or possibly the Salmagundi Club Prize awarded there). The following year, 1901, he won a Silver Medal at the Pan-American Exposition held in Buffalo, New York.

Further accolades followed quickly. He was awarded another Silver Medal at the Charleston Exposition in 1902. One of his most significant honors came in 1904 at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (the St. Louis World's Fair), where he again secured a Silver Medal. That same year, 1904, the National Academy of Design bestowed upon him the prestigious Inness Gold Medal, an award named in honor of his late friend and mentor, George Inness, specifically recognizing achievement in landscape painting. His international reputation was further cemented in 1906 when he won a Gold Medal at the Paris Salon, organized by the Société des Artistes Français. Beyond awards, Eaton was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design in 1897 and achieved full Academician status in 1901. He was also an active member of important artist organizations like the Salmagundi Club and the Lotos Club in New York City.

Enduring Legacy and Critical Reception

Charles Warren Eaton's legacy rests firmly on his contributions to American Tonalism. He was a leading figure in the movement, admired for his technical skill, his consistent artistic vision, and the deeply felt poetry of his landscapes. During his lifetime, particularly in the first two decades of the 20th century, he enjoyed considerable popularity and commercial success. His evocative pine tree paintings, in particular, found a ready market among collectors who appreciated their quiet beauty and meditative quality.

Like many Tonalist painters, Eaton's reputation experienced a decline with the rise of Modernism in the post-World War I era. Tastes shifted towards abstraction, social realism, and other avant-garde styles, and the introspective, subtly rendered landscapes of Tonalism fell out of favor for a time. However, beginning in the latter half of the 20th century, there has been a significant scholarly and critical reappraisal of Tonalism. Art historians recognized its importance as a distinctly American artistic expression, bridging the gap between 19th-century Romanticism and 20th-century modern sensibilities.

Within this revival, Charles Warren Eaton has been rightfully acknowledged as a master of the style. His work is praised for its technical refinement, its consistent emotional depth, and its unique focus on particular motifs like the white pine. Today, his paintings are held in the permanent collections of major American museums, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., the Brooklyn Museum in New York, the Montclair Art Museum in New Jersey (which has a significant collection of Tonalist works), and numerous other public and private collections across the country. He is remembered as an artist who captured the quiet soul of the American landscape with profound sensitivity and enduring artistry.

Conclusion

Charles Warren Eaton carved a distinct and respected place for himself in American art history. From his determined beginnings studying art by night in New York City, he rose to become a leading exponent of Tonalism, developing a signature style characterized by moody atmospheres, subtle color harmonies, and an intimate connection with nature. His evocative depictions of the New England landscape, particularly his iconic paintings of pine trees under twilight or moonlight, earned him the affectionate title "The Pine Tree Painter" and secured his reputation among collectors and critics. Though his fame waned temporarily with shifting artistic tastes, his work has since been re-evaluated and celebrated for its poetic beauty and technical mastery. Eaton's enduring legacy lies in his ability to translate the quiet, introspective moods of the natural world onto canvas, creating landscapes that continue to speak to viewers seeking solace, beauty, and a connection to the timeless rhythms of nature.