Martinus Rørbye (17 May 1803 – 29 August 1848) stands as a pivotal figure in the Danish Golden Age of painting, a period of extraordinary artistic output in Denmark during the first half of the 19th century. Born in Drammen, Norway, Rørbye's life and career became intrinsically linked with Denmark after his family relocated there. He is celebrated for his evocative landscape paintings, insightful genre scenes, and pioneering Orientalist works, which brought a wider world to the Danish canvas. His art skillfully blended the prevailing currents of Romanticism with a keen sense of Realism, capturing both the sublime beauty of nature and the nuanced details of human life.

Rørbye's artistic journey was marked by extensive travels, a characteristic that distinguished him from many of his Danish contemporaries. These voyages not only broadened his personal horizons but also profoundly influenced his thematic choices and artistic style, allowing him to depict a diverse range of settings from the familiar Danish countryside to the sun-drenched landscapes of Italy and the bustling, exotic locales of Greece and the Ottoman Empire.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Copenhagen

Martinus Christian Wesseltoft Rørbye was born into a family with administrative connections; his father was a warehouse manager and later a customs inspector. The family's move to Copenhagen when Martinus was around twelve years old placed him in the cultural heart of Denmark. It was here that his artistic inclinations began to take shape. He commenced his formal art education around 1820 at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts (Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi).

At the Academy, Rørbye studied under prominent figures of the era. Initially, he was a student of Christian August Lorentzen, a painter known for his landscapes, portraits, and historical scenes, who represented an older, more traditional approach. However, the most significant influence on Rørbye's development came from Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, often hailed as the "Father of Danish Painting." Rørbye joined Eckersberg's painting school in 1823 and became one of his most favored pupils, developing a close personal and professional relationship with his mentor. Eckersberg emphasized direct observation of nature, meticulous attention to detail, clear composition, and an objective rendering of reality, principles that deeply informed Rørbye's own artistic practice.

Despite his talent and dedication, Rørbye, like many aspiring artists, faced the competitive environment of the Academy. He made several attempts to win the Academy's prestigious large gold medal, which would have provided a substantial travel stipend, but was unsuccessful in this particular endeavor. Nevertheless, his abilities were recognized, and he did receive smaller awards and eventually secured funding for his crucial travels abroad.

The Grand Tour and Its Impact: Italy, Greece, and Turkey

Travel was a cornerstone of Rørbye's artistic identity. In an era when many Danish artists focused primarily on their homeland, Rørbye was an inveterate explorer. His first major journey, undertaken between 1834 and 1837, was financed by a travel stipend from the Academy. This extensive tour took him through Germany to Paris, and then onwards to Italy, Greece, and Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) in the Ottoman Empire. Such an itinerary was ambitious and, particularly the extension to the Ottoman lands, relatively uncommon for Danish artists of his generation.

Italy, as for many Northern European artists, was a revelation. He spent considerable time in Rome, the artistic mecca, where he immersed himself in its classical ruins, Renaissance art, and vibrant contemporary artistic community. He associated with other Scandinavian and German artists residing there, including the renowned Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, who was a dominant figure in Rome's art scene, and the German painter Edmond Blunck. Rørbye's Roman daily routine, as recorded in his diaries, involved morning sketching expeditions in the city or surrounding Campagna, followed by evenings spent socializing with fellow artists like the Jensens and Wulffs. It was also in Italy that he formed a friendship with the writer Hans Christian Andersen, whose own travel narratives may have been spurred by Rørbye's enthusiastic accounts.

One charming anecdote from his Italian sojourn illustrates his dedication. While painting in Amalfi, he rented a room in a former monastery and reportedly hired a local man to keep the curious onlookers at bay, allowing him to concentrate on capturing the lively scenes, such as in his work Public Square in Amalfi. This painting showcases his skill in depicting bustling everyday life with a wealth of detail and character.

His travels extended beyond Italy to Greece, where he sketched ancient monuments and absorbed the Mediterranean light and atmosphere. However, it was his visit to Constantinople that proved particularly formative for his interest in Orientalist themes. He was one of the first Danish painters to explore the Ottoman Empire extensively, and his depictions of Turkish life, architecture, and customs were groundbreaking in Danish art.

Orientalism and Exotic Vistas

Rørbye's fascination with the "Orient" – a term then used broadly to describe cultures of North Africa, the Middle East, and Turkey – became a significant aspect of his oeuvre. His paintings from Constantinople and other parts of the Ottoman Empire are characterized by a careful observation of local customs, attire, and architecture, distinguishing them from the more fantastical or stereotyped Orientalist works of some of his European contemporaries like the French master Eugène Delacroix, whose Moroccan scenes were often more dramatic and less ethnographic.

A prime example of Rørbye's Orientalist work is A Turkish Notary drawing up a Marriage Contract in front of the Kılıç Ali Pasha Mosque, Tophane, Constantinople (1837). This painting meticulously details the figures, their clothing, the architectural setting of the mosque, and the everyday street life unfolding around the central event. It demonstrates Rørbye's ability to combine genre painting with an ethnographic eye, offering Danish audiences a vivid glimpse into a distant culture. Another work, often simply titled Tophane Kılıç Ali Paşa Mosque, further explores these themes. His approach, while still viewed through a European lens, often aimed for a degree of authenticity and sympathetic portrayal.

His interest in the exotic was not limited to the Ottoman Empire. Even his Italian scenes, such as views from Procida capturing volcanic landscapes and panoramic beauty, convey a sense of wonder and a desire to capture the unique character of foreign lands. This engagement with diverse cultures and landscapes significantly enriched the Danish Golden Age, which, while excelling in depictions of Danish life and nature, benefited from Rørbye's broader, more cosmopolitan perspective.

Artistic Style: Romanticism, Realism, and the Influence of Eckersberg

Martinus Rørbye's artistic style is a nuanced fusion of Romanticism and Realism. From Romanticism, he adopted an interest in the subjective experience, the evocative power of landscape, and a fascination with the exotic and the historical. This is evident in the atmospheric qualities of his paintings, the sense of longing or contemplation often found in his figures, and his choice of subjects from distant lands or historical settings.

His work often features the motif of the open window, a common trope in German Romantic painting, particularly associated with Caspar David Friedrich. For Rørbye, as for Friedrich, the window looking out onto a landscape or seascape could symbolize a yearning for the unknown, a bridge between the intimate interior world and the vastness of the exterior, or a moment of quiet reflection. His iconic painting, View from the Artist's Window (1825), perfectly encapsulates this, depicting the view from his childhood home with ships in the harbor, suggesting both a connection to home and the allure of distant voyages.

Simultaneously, Rørbye was deeply indebted to the teachings of Eckersberg, which instilled in him a commitment to Realism. This is apparent in his precise draughtsmanship, his careful attention to detail, the clarity of his compositions, and his objective rendering of light and texture. Eckersberg encouraged painting en plein air (outdoors) for studies, and this practice of direct observation is evident in the freshness and authenticity of Rørbye's landscapes and architectural scenes. He masterfully captured the specific quality of light in different environments, from the cool, clear light of Denmark to the warm, intense sunlight of the Mediterranean.

His genre scenes, whether set in Denmark or abroad, are characterized by this realistic approach. He depicted everyday people engaged in ordinary activities, but with an eye for the telling detail that could reveal character or social context. Works like The Surgeon Christian Fenger and his Family show his ability to create intimate and insightful group portraits that also function as genre scenes, reflecting the values and social structures of the Biedermeier period.

Key Works and Thematic Concerns

Beyond the already mentioned View from the Artist's Window and A Turkish Notary, several other works highlight Rørbye's diverse talents and thematic interests.

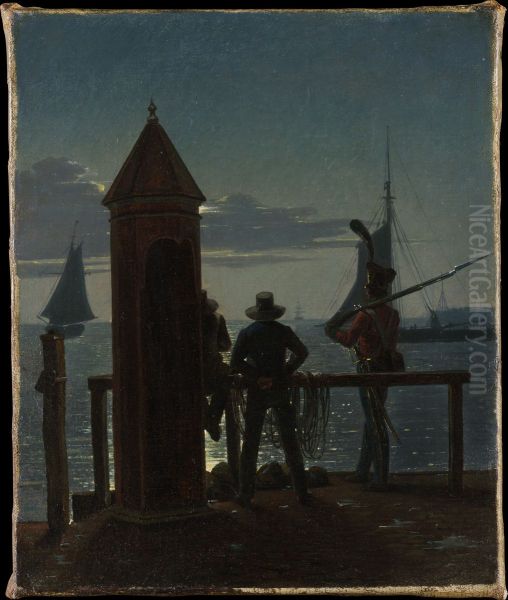

View from the Citadel Ramparts by Moonlight, Copenhagen: This painting showcases Rørbye's skill in capturing nocturnal scenes and the romantic atmosphere of moonlight. The depiction of the historic Citadel (Kastellet) under an evocative moonlit sky combines topographical accuracy with a poetic sensibility, a hallmark of Danish Golden Age landscape painting, also seen in the works of contemporaries like Christen Købke.

An Arcaded Courtyard at the Doge's Palace, Venice: His Italian scenes often focused on architectural studies, capturing the interplay of light and shadow in historic structures. This work would reflect his careful observation of Venetian architecture, a popular subject for artists on the Grand Tour, including international figures like J.M.W. Turner or Camille Corot, who also painted extensively in Italy.

Prisoners in the Stocks at the Town Hall in Vejle: This painting is a starker example of his genre work, depicting a scene of public punishment. It reflects an interest in social realities and historical customs, rendered with his characteristic attention to detail.

Armebygningen ved Tårn- og Domhus (The Paupers' Building by the Tower and Courthouse): This work likely depicts a specific Copenhagen scene, again highlighting his interest in the urban landscape and its social fabric, a theme also explored by Wilhelm Bendz in his detailed interior genre scenes.

Rørbye's landscapes, whether Danish or foreign, often convey a sense of tranquility and order, even when depicting wild nature. He shared with other Golden Age painters like P.C. Skovgaard or J.Th. Lundbye a deep appreciation for the Danish landscape, but his unique contribution was to place these national scenes within a broader European and Near Eastern context.

A Cosmopolitan Dane: Interactions and Perspectives

Rørbye's extensive travels naturally brought him into contact with a wide array of artists and intellectuals across Europe. In Paris, he would have encountered the vibrant French art scene, possibly engaging with artists influenced by or reacting against the Neoclassicism of Jacques-Louis David or the burgeoning Romanticism of Théodore Géricault. The provided information mentions contact with French artists like Peter Andreas Heiberg (a Danish-French writer), the choreographer Auguste Bournonville (who had strong French connections), and the great Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, whose precision and clarity might have resonated with Rørbye's Eckersbergian training.

His time in Rome was particularly rich in artistic exchange. Besides Thorvaldsen and Blunck, he would have been aware of the Nazarene movement, a group of German Romantic painters (like Johann Friedrich Overbeck and Peter von Cornelius) who sought to revive Christian art and were highly active in Rome. While Rørbye's style differed, the intellectual ferment of this international artistic community undoubtedly stimulated him.

Rørbye was not uncritical of his fellow Danish artists. He reportedly lamented what he perceived as their lack of adventurousness and their preference for the comforts of home over the enriching experiences of travel. For him, travel was not mere sightseeing; it was an essential means of artistic and personal growth, involving genuine interaction with local cultures. This perspective underscores his own pioneering spirit and his desire to push the boundaries of Danish art.

Later Years, Professorship, and Legacy

Upon his return to Denmark in 1837, Rørbye's reputation was considerably enhanced by his travels and the works he brought back. He became a member of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 1838. His experiences abroad, particularly his Orientalist paintings, brought a new dimension to the Danish art scene. He continued to paint Danish landscapes and genre scenes, but his palette and thematic range had been irrevocably broadened.

In 1844, Rørbye achieved a significant academic milestone when he was appointed professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, a testament to his standing within the Danish art establishment. In this role, he would have had the opportunity to influence a new generation of artists, passing on the principles he had learned from Eckersberg, enriched by his own extensive experiences. One of his known private students was Christian Dalsgaard, who himself became a notable painter of Danish folk life.

Tragically, Martinus Rørbye's life was cut short. He died in Copenhagen on August 29, 1848, at the relatively young age of 45. Despite his premature death, he left behind a significant body of work that continues to be celebrated.

His legacy is multifaceted. He is a key representative of the Danish Golden Age, embodying its synthesis of meticulous observation and poetic sensibility. His depictions of Danish life and landscape contribute to the rich tapestry of national Romanticism. Furthermore, his extensive travels and his pioneering Orientalist works mark him as one of Denmark's most cosmopolitan artists of the period, a painter who looked both inward to his national heritage and outward to the wider world. His paintings are prized for their technical skill, their evocative beauty, and the unique window they offer onto the diverse cultures and landscapes he encountered. Today, his works are prominently featured in the Statens Museum for Kunst (National Gallery of Denmark) and other major Danish museums, as well as in private collections, securing his place as an enduring master of Danish art. His influence can be seen in later Danish artists who continued to explore genre scenes, such as Wilhelm Marstrand, or those who also ventured abroad, like Constantin Hansen, who also painted memorable scenes from Italy. Rørbye's adventurous spirit and his ability to translate his experiences into compelling art remain an inspiration.