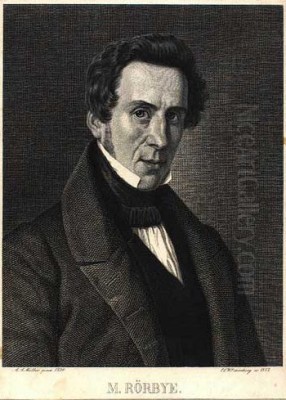

Martinus Christian Wesseltoft Rørbye stands as one of the most significant and well-travelled painters of the Danish Golden Age, a period of exceptional artistic and cultural flourishing in Denmark during the first half of the 19th century. His meticulous attention to detail, his keen eye for the effects of light and atmosphere, and his ethnographic curiosity set him apart. Rørbye's extensive travels not only broadened his own artistic horizons but also brought back a wealth of imagery that enriched Danish art, offering glimpses into distant lands and cultures. His work bridges the precise observational style of his teacher, Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, with a burgeoning Romantic sensibility, making him a pivotal figure in the transition of Danish art.

Early Life and Formative Education

Martinus Rørbye was born on May 17, 1803, in Drammen, Norway, where his father, Ferdinand Henrik Rørbye, served as a warehouse manager and later a war commissioner. His mother was Frederikke Eleonore Cathrine de Stockfleth. The political landscape of Scandinavia shifted dramatically in 1814 when Norway, previously united with Denmark, was ceded to Sweden. This event prompted the Rørbye family to relocate to Denmark, a move that would prove decisive for young Martinus's future artistic career.

Upon settling in Copenhagen, Rørbye embarked on his artistic training. He enrolled at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts (Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi) around 1820. Initially, he studied under Christian August Lorentzen, a painter known for his historical scenes, landscapes, and portraits, who represented an older, more traditional approach that blended Neoclassicism with early Romantic tendencies. Lorentzen's influence can be seen in Rørbye's early attention to color and narrative.

However, the most profound influence on Rørbye's development came from Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, who is widely regarded as the "Father of Danish Painting" and the central figure of the Danish Golden Age. Rørbye became one of Eckersberg's private pupils from 1822. Eckersberg, himself trained by Jacques-Louis David in Paris, instilled in his students a rigorous discipline based on direct observation of nature, meticulous rendering of detail, and a strong understanding of perspective and the play of light. He encouraged outdoor sketching and a truthful depiction of reality, which became hallmarks of the Golden Age. Rørbye absorbed these principles deeply, and Eckersberg considered him one of his most talented students.

Despite his talent and dedication, Rørbye did not achieve the Academy's highest accolades easily. He received the small silver medal in 1824 and the large silver medal in 1828. He vied for the large gold medal, which came with a crucial travel stipend, on several occasions but was unsuccessful. However, in 1829, his painting "Christ Healing the Blind" earned him a cash prize, providing some financial means for his artistic pursuits.

Artistic Development and Key Influences

Rørbye's artistic style evolved under the tutelage of Eckersberg, embracing the latter's emphasis on realism, clarity, and detailed observation. Yet, Rørbye's work also reveals a sensitivity to the Romantic currents sweeping across Europe. His landscapes and genre scenes often possess a quiet, contemplative mood, and his fascination with the exotic and the picturesque, particularly evident in his later travel paintings, aligns with Romantic sensibilities.

The influence of German Romantic painters, such as Caspar David Friedrich and the Norwegian-born Johan Christian Dahl (who was based in Dresden), can be discerned in some of Rørbye's works, particularly in their atmospheric qualities and the way figures are often integrated into landscapes to evoke a sense of scale or introspection. Dahl, in particular, was a significant figure for Scandinavian artists, bridging German Romanticism with a specific focus on Nordic landscapes.

Rørbye was an inveterate traveller, a characteristic that significantly shaped his oeuvre. His journeys began within Scandinavia. He made several trips to Norway in the early 1830s (e.g., 1830, 1832), capturing its dramatic landscapes and traditional life. These trips allowed him to explore his Norwegian heritage and paint scenes that were novel to the Danish audience. He also painted views of Copenhagen and its surroundings, often focusing on architectural subjects and everyday life, rendered with the precision learned from Eckersberg.

One of his most famous early works, "View from the Artist's Window" (ca. 1825), is a quintessential Danish Golden Age painting. It depicts the view from his childhood home, with ships in the harbor visible beyond the meticulously rendered window frame, complete with potted plants and a birdcage. The painting masterfully combines domestic intimacy with a glimpse of the wider world, a common theme in Biedermeier art, and showcases his skill in perspective and light.

The Grand Tour and Orientalist Visions

Like many artists of his era, Rørbye yearned to undertake the Grand Tour to Italy, the traditional finishing school for aspiring European artists. He finally received a travel stipend from the Academy in 1834, enabling him to embark on an extensive journey that would last until 1837. This period was transformative for his art.

He travelled south through Germany and arrived in Rome, the epicenter of artistic pilgrimage. In Rome, he joined a vibrant community of Danish and other Nordic artists. He frequented the studio of the renowned Danish Neoclassical sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, a towering figure who acted as a mentor and patron to many Scandinavian artists in the city. Rørbye painted Thorvaldsen's portrait and depicted scenes within his bustling studio. He also associated with fellow Danish painters like Constantin Hansen, Wilhelm Marstrand, Jørgen Roed, and the architect Michael Gottlieb Bindesbøll, as well as other Nordic artists such as the Swede Egron Lundgren and the Norwegian Thomas Fearnley. The Caffè Greco was a popular meeting spot for these artists.

Rørbye's Italian works include landscapes of the Roman Campagna, views of ancient ruins, and lively genre scenes depicting local customs and people. He painted in Sorrento, Amalfi, and Sicily, capturing the brilliant Mediterranean light and vibrant colors. His painting "A Public Square in Amalfi" (1835) is a fine example of his ability to combine architectural accuracy with lively depictions of daily life.

Unusually for a Danish artist of his time, Rørbye extended his travels beyond Italy. In 1835-1836, he journeyed to Greece, visiting Athens and other classical sites. This was a more adventurous undertaking, as Greece had only recently gained independence from the Ottoman Empire. His Greek landscapes and architectural studies are imbued with a sense of history and the picturesque decay of ancient monuments.

From Greece, he ventured further east to Constantinople (Istanbul) in the Ottoman Empire, becoming one of the first Danish artists to explore the "Orient." This experience profoundly impacted his work, leading to a series of Orientalist paintings that were highly novel in Denmark. He was fascinated by the exotic architecture, colorful costumes, and bustling street life. Works like "A Turkish Notary drawing up a Marriage Contract before the Kiliç Ali Pasha Mosque, Tophane, Constantinople" (1837) and "View of the Square of the Emirgan Mosque on the Bosphorus" (1836) are rich in ethnographic detail and atmospheric effects, capturing the vibrant, multicultural environment of the Ottoman capital. His interest in Orientalist themes may have been influenced by French painters like Jean-François Véron or Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, whose works were becoming known.

Return to Denmark and Later Career

Rørbye returned to Copenhagen in 1837, his portfolio filled with sketches and studies from his extensive travels. These materials would provide inspiration for paintings for the rest of his career. He became a member of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 1838, submitting "A Turkish Notary..." as his reception piece.

In the following years, he continued to paint landscapes, genre scenes, and portraits. He revisited themes from his travels, producing finished oil paintings based on his sketches. He also painted Danish scenes, including views of Jutland. Notably, Rørbye was one of the first academically trained artists to paint in Skagen, the northernmost tip of Jutland, visiting in 1833 and again in 1847. His depictions of the local fishermen, the distinctive landscape, and the unique light of Skagen predate the famous Skagen Painters' colony (which included artists like Michael Ancher, Anna Ancher, and P.S. Krøyer) by several decades, making him a significant precursor to that important artistic movement.

His work "Men of Skagen on a Summer Evening in Good Weather" (1848), painted in the last year of his life, is a poignant depiction of the Skagen fishermen and captures the special atmosphere of the region. He also undertook commissions for altarpieces and portraits, such as "The Surgeon Christian Fenger with his Wife and Daughter" (1842), which, while a portrait, also subtly comments on contemporary bourgeois family life and gender roles.

Rørbye was appointed professor at the Academy's model school in 1844, a position that allowed him to pass on his knowledge and Eckersberg's principles to a new generation of artists. Among his students was Lorenz Frølich, who would become a notable illustrator and painter.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Techniques

Rørbye's style is characterized by a meticulous realism inherited from Eckersberg, particularly in his attention to detail, precise drawing, and the careful rendering of light and texture. His compositions are generally well-balanced and clearly structured. He had a fine sense of color, often employing a bright, clear palette, especially in his Mediterranean and Orientalist scenes.

His thematic range was broad. Landscapes formed a significant part of his output, from the dramatic fjords of Norway and the sun-drenched plains of Italy to the ancient ruins of Greece and the coastal dunes of Skagen. Genre scenes, depicting everyday life and local customs, were another specialty. These often had an ethnographic quality, reflecting his keen observation of people and their environments. His Orientalist works stand out for their novelty and detailed depiction of a culture largely unfamiliar to his Danish audience.

Rørbye was a diligent sketcher, and his travels resulted in numerous drawings and oil sketches made on site. These sketches, often fresh and spontaneous, formed the basis for more finished studio paintings. It is known that Rørbye, like some of his contemporaries, sometimes produced multiple versions of his popular compositions, a practice that catered to market demand but has occasionally raised questions among art historians about originality versus repetition. This practice, however, was not uncommon and often involved subtle variations or refinements in subsequent versions. His use of detailed preparatory drawings and perhaps even tracing for transferring compositions was in line with academic practices of the time.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several of Rørbye's paintings have become iconic representations of the Danish Golden Age and his unique artistic journey.

"View from the Artist's Window" (ca. 1825, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen): This early masterpiece perfectly encapsulates the Biedermeier spirit of the Danish Golden Age. The meticulously rendered interior, with its symbols of domesticity (potted plants, a caged bird), contrasts with the view of the harbor and ships, suggesting a yearning for the wider world. The play of light and the precise depiction of objects are hallmarks of Eckersberg's influence.

"The Prison of Copenhagen" (1831, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen): An example of his architectural painting, this work depicts the newly built Copenhagen city jail, designed by C.F. Hansen. Rørbye focuses on the imposing structure, using light and shadow to emphasize its stark geometry, but also includes small figures to give a sense of scale and daily life around it.

"A Turkish Notary drawing up a Marriage Contract before the Kiliç Ali Pasha Mosque, Tophane, Constantinople" (1837, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen): This was Rørbye's reception piece for the Academy. It is a vibrant, detailed scene capturing a moment of everyday life in Istanbul. The painting showcases his skill in depicting exotic costumes, intricate architectural details, and the unique atmosphere of the city. It reflects the growing European fascination with the "Orient."

"View of Athens from the West" (1836, Thorvaldsens Museum, Copenhagen): This painting shows the Acropolis and the city of Athens, bathed in the clear Greek light. It combines topographical accuracy with a Romantic sense of history, depicting the ancient monuments as enduring symbols of classical civilization.

"Men of Skagen on a Summer Evening in Good Weather" (1848, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen): One of his last major works, this painting is a sensitive portrayal of the fishermen of Skagen. The figures are depicted with dignity against the backdrop of the beach and the calm sea, under a luminous evening sky. It anticipates the later Skagen Painters' interest in the local population and the unique light of the region.

"View of Citadel Ramparts by Moonlight" (undated): This work demonstrates Rørbye's ability to capture different times of day and atmospheric conditions. The moonlight creates a poetic and slightly melancholic mood, highlighting his Romantic inclinations.

Legacy and Re-evaluation

Martinus Rørbye's health began to decline in the mid-1840s, possibly due to stomach cancer. He passed away on August 29, 1848, in Copenhagen, at the relatively young age of 45. His death marked the loss of a significant talent in Danish art.

For a period, Rørbye's work, like that of many Danish Golden Age painters, was somewhat overshadowed by later artistic movements. However, renewed art historical interest in the 20th century led to a re-evaluation of his contributions. Today, he is recognized as one of the leading figures of his generation, an artist who skillfully combined the meticulous realism of the Eckersberg school with a broader, more Romantic and cosmopolitan outlook shaped by his extensive travels.

His influence can be seen in several areas. As a teacher at the Academy, he helped perpetuate the Eckersberg tradition while also bringing his own experiences to his pedagogy. His early depictions of Skagen were pioneering, paving the way for the later artists' colony that would make the area famous. His Orientalist paintings introduced new subject matter to Danish art and contributed to the European fascination with the East.

Rørbye's works are well-represented in major Danish museums, particularly the Statens Museum for Kunst (National Gallery of Denmark) in Copenhagen, as well as in numerous private collections. His travel diaries and sketchbooks provide invaluable insights into his working methods and his observations of the places he visited.

He remains a testament to the spirit of the Danish Golden Age – an era of intense artistic inquiry, a deep connection to both local environment and classical heritage, and an opening up to the wider world. Martinus Rørbye, through his life and art, embodied this spirit of exploration and meticulous craftsmanship, leaving behind a rich and varied body of work that continues to captivate and inform. His contemporaries, such as Christen Købke, Wilhelm Bendz, Constantin Hansen, Jørgen Roed, and Wilhelm Marstrand, alongside landscape specialists like P.C. Skovgaard and Johan Thomas Lundbye, all contributed to this remarkable period, but Rørbye's extensive travels gave his art a unique international dimension.

Conclusion

Martinus Rørbye was more than just a skilled painter; he was an observer, a traveller, and a chronicler of his times. His art offers a window into the Danish Golden Age, but also into the landscapes and cultures of Norway, Italy, Greece, and the Ottoman Empire as they appeared in the 1830s. He successfully navigated the artistic currents of his time, blending the rigorous observational demands of Eckersberg's teachings with a personal, often Romantic, sensibility. His dedication to capturing the truth of what he saw, whether it was the familiar view from his window in Copenhagen or an exotic scene in Constantinople, resulted in a body of work that is both historically significant and aesthetically compelling. His legacy endures, not only in his beautiful paintings but also in his role as a bridge between cultures and as an inspiration for subsequent generations of artists.